Matteo Tonello is Director of Corporate Governance for The Conference Board, Inc. This post is based on a Conference Board Director Note by Andrew L. Bab and Sean P. Neenan. Additional posts about poison pills, including several from the Program on Corporate Governance, can be found here.

Having been buffeted by sustained attacks from activists and proxy voting advisors in past years, the shareholder rights agreement is no longer as prevalent as it once was—a phenomenon that has been documented by many corporate governance observers like The Conference Board. However, the most recent case law confirms the validity of poison pills that are properly structured, adopted, and administered. This report discusses these new trends and provides guidance to boards considering whether to adopt a pill and how to formulate its terms.

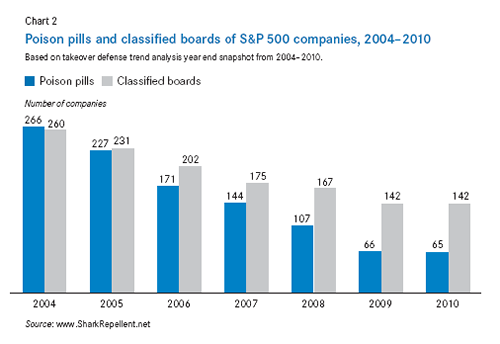

Despite the continued decline in the number of outstanding poison pills maintained by U.S. public companies, Delaware courts in several cases in 2010 and early 2011 have steadfastly confirmed the continuing legal vitality of pills that are properly structured, adopted, and administered. The most recent of these cases demonstrates how powerful a poison pill can be when working in tandem with a classified board: Air Products withdrew its 16-month long hostile pursuit of Airgas promptly after the Delaware Court of Chancery upheld Airgas’ combined defenses. [1] It is interesting, therefore, that fewer and fewer companies are maintaining classified boards; companies may find that without them, the effectiveness of their poison pills will be significantly reduced.

Two novel uses of poison pills were tested in the Delaware courts in 2010. In one case, a poison pill established to protect a company’s net operating loss carryforwards (NOLs) emerged unscathed, while another pill, implemented to protect the company’s unique corporate culture, did not survive scrutiny. [2,3]

Background

The shareholder rights agreement (or “poison pill”) first became popular in the 1980s as a way to provide a target board with negotiating leverage in the face of a hostile takeover attempt. Today, despite a widely documented decline in its prevalence over the past five to 10 years, the poison pill continues to be an effective anti-takeover tool for public corporations. [4] Indeed, a company board that does not maintain a poison pill in the ordinary course may nonetheless, in general and subject to its fiduciary duties, adopt a pill swiftly in response to a particular hostile overture.

Poison pills are generally aimed at protecting shareholders against a change of control transaction that fails to provide them with an appropriate control premium. A corporation customarily installs a poison pill through board action. Rights dividends awarded to the corporation’s stockholders automatically attach to the holders’ shares of common stock. If a potential acquirer increases its “beneficial ownership” of the corporation’s common stock in excess of a certain threshold percentage (usually 10 to 20 percent), all shareholders — except the potential acquirer — may purchase additional shares at a deep discount, thereby substantially diluting the acquirer’s position.

Much depends on how the pill documents define “beneficial ownership.” Is the definition broad enough to capture a “group” of shareholders acting in concert who jointly hold more than the threshold percentage, but who individually own less than the same threshold percentage? Is the definition broad enough to cover all relevant forms of indirect economic ownership, including ongoing developments in derivative instruments? Some commentators have questioned whether the standard beneficial ownership language is sufficient, and some companies have experimented with more expansive language.

The decision of a Delaware corporation’s board to implement a poison pill (or refuse to redeem an already adopted pill) in response to a perceived threat to the corporation will generally be measured against the Unocal standard: [5]

- 1. Did the board show that it reasonably believed that a threat to corporate effectiveness and policy existed?

- 2. If so, was the board’s response coercive or preclusive, or was it outside the range of reasonable responses to the threat?

The decline of the 1980s poison pill

Over the past decade, fewer and fewer public companies have maintained traditionally structured poison pills. In 2001, more than 2,200 corporations had poison pills in effect; a January 4, 2011 search through Capital IQ found that fewer than 900 corporations had poison pills in effect. [6,7] In recent years, the number of smaller companies adopting such pills has increased, while many larger companies have allowed their in-force pills to expire. [8] Moreover, fewer pills are being adopted in the absence of a specific threat, and more of those adopted are aimed at protecting NOLs instead of a potential control premium (Chart 1). [9]

Over the past decade, fewer and fewer public companies have maintained traditionally structured poison pills. In 2001, more than 2,200 corporations had poison pills in effect; a January 4, 2011 search through Capital IQ found that fewer than 900 corporations had poison pills in effect. [6,7] In recent years, the number of smaller companies adopting such pills has increased, while many larger companies have allowed their in-force pills to expire. [8] Moreover, fewer pills are being adopted in the absence of a specific threat, and more of those adopted are aimed at protecting NOLs instead of a potential control premium (Chart 1). [9]

One reason for the decline in traditional poison pills has been the increase in pressure from shareholder activists and other institutional investors to remove them. They argue that poison pills and other takeover defenses can entrench management and unfairly deprive shareholders of a potentially significant and current return on their investment. In addition, Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) revised its guidance for the 2010 proxy season in a manner likely to continue the downward trend in the number of poison pills. In the past, ISS had recommended that shareholders vote against or withhold their votes for directors who voted to adopt or renew a poison pill of any duration without shareholder approval (or without commitment to put the pill up for shareholder approval within 12 months of adoption or renewal). [10]

However, beginning with the 2010 proxy season, ISS started to recommend a vote against or withhold vote for any director of a corporation up for election who voted to:

- adopt a poison pill with a term of more than 12 months;

- renew a poison pill of any duration without shareholder approval; or

- make a material adverse change to any existing poison pill without shareholder approval.

Prior to this revision, ISS would have made a voting recommendation only in the year that the pill was implemented or renewed. Under the revised guidelines, a director’s voting record on the company’s poison pill may factor into ISS’s recommendation concerning that director every time he or she is up for election. ISS did note that a commitment by the directors to put newly adopted pills up for a binding shareholder vote may offset an adverse vote recommendation. [11]

ISS 2011 Proxy Vote Recommendation Regarding Board Members and Poison Pills

Vote withhold/against the entire board of directors (except new nominees, who should be considered case-by-case), for the following:

Poison pills:

1.3 The company’s poison pill has a “dead-hand” or “modified dead-hand” feature. Vote withhold/against every year until this feature is removed;

1.4 The board adopts a poison pill with a term of more than 12 months (“long-term pill”), or renews any existing pill, including any “short-term” pill (12 months or less), without shareholder approval. A commitment or policy that puts a newly adopted pill to a binding shareholder vote may potentially offset an adverse vote recommendation. Review such companies with classified boards every year, and such companies with annually elected boards at least once every three years, and vote against or withhold votes from all nominees if the company still maintains a non-shareholder-approved poison pill. This policy applies to all companies adopting or renewing pills after the announcement of this policy (November 19, 2009);

1.5 The board makes a material adverse change to an existing poison pill without shareholder approval.

Vote case-by-case on all nominees if:

1.6 The board adopts a poison pill with a term of 12 months or less (“short-term pill”) without shareholder approval, taking into account the following factors:

• the date of the pill’s adoption relative to the date of the next meeting of shareholders—i.e., whether the company had time to put the pill on ballot for shareholder ratification given the circumstances;

• the issuer’s rationale;

• the issuer’s governance structure and practices; and

• the issuer’s track record of accountability to shareholders.

Source: Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc., 2011 U.S. Proxy Voting Guidelines Summary, December 16, 2010 (www.issgovernance.com/files/ISS2011USPolicySummaryGuidelines20101216.pdf)

The decline of board classification

Just as poison pills can be implemented legally through board action alone, so can they usually only be dismantled by board action, either through amendment or redemption of rights. An acquirer who is unable to convince a board of the merits of its offer may appeal to the shareholders, but only by asking them to replace a majority of the current board with candidates more receptive to the acquirer’s bid.

For this reason, the effectiveness of a poison pill is enhanced if the target company has a staggered board, which would typically provide for three classes of directors with only one class up for election each year. To replace a majority of a determined target’s board, the acquirer would need to win two consecutive annual proxy contests—a formidable task.

Indeed, once the Delaware Court of Chancery refused to require Airgas to redeem its poison pill, Air Products, already the winner of one election contest, nevertheless felt compelled to withdraw its $5.9 billion hostile offer for Airgas rather than wait another seven to eight months to try its luck at winning a second vote. And yet, whether at the behest of activist shareholders or on their own accord, many companies no longer have staggered boards. Only 142 of S&P 500 companies currently have staggered boards, compared to 260 at the end of 2004. [12,13] And although a poison pill may often be adopted rapidly by board action in the face of a surprise unsolicited offer, creating a staggered board generally requires a time consuming, often unpredictable shareholder vote.

The “NOL Pill”: Versata v. Selectica

Many companies have amassed significant NOLs due in part to the recent financial crisis. Because NOLs can be used to offset future taxable income, they can be a valuable corporate asset. However, the use of existing NOLs to offset profits can be impaired if a company undergoes an “ownership change,” as defined in Section 382 of the Internal Revenue Code. [14] Although the determination of whether an ownership change has occurred is extremely fact specific and complex, one trigger is a change in the stock ownership of the corporation by more than 50 percent over a rolling three-year period. However, under Section 382, only those shareholders of 5 percent or more of a company’s stock are generally considered in the analysis.

To protect their NOLs, a number of corporations have installed poison pills with triggers below 5 percent (typically 4.99 percent), which, considering that most traditional pills have triggers between 10 percent and 20 percent, is relatively low. Approximately 60 of these “NOL pills” were in place when a Capital IQ search was performed in January 2011. [15] Prior to the 2009 proxy season, ISS would not differentiate NOL pills from traditional ones. Today, the proxy advisor firm recommends that any proposal to implement an NOL pill be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, unless the proposal refers to NOL pills that do not automatically expire on or prior to the earlier of the pills’ third anniversary and the exhaustion of the NOLs, in which case the proposal should be voted against. [16]

In the 2010 decision Versata v. Selectica, the Delaware Supreme Court upheld the validity of an NOL pill despite its low trigger. [17] The decision affirmed a prior decision of the Delaware Court of Chancery that Selectica, Inc., a micro-cap software company, had not acted improperly by allowing its NOL pill to be exercised when one of its shareholders and competitors, Versata Enterprises, Inc., intentionally tripped the 4.99 percent threshold. [18]

Since it became a public company, Selectica had never made a profit; on the contrary, it amassed $160 million in NOLs over its lifetime. Versata had a complicated relationship with Selectica, having previously made acquisition offers to Selectica’s board and brought a patent infringement suit against Selectica that ultimately resulted in Versata being awarded $17.5 million in damages. In November 2008, Versata, after Selectica rejected its takeover bid, began purchasing shares of Selectica on the open market.

Selectica knew that its NOLs were a valuable asset and commissioned an update of studies it had requested in the past to determine whether the company was currently at risk of undergoing an “ownership change” under Section 382. In light of Versata’s recent open market purchases of Selectica shares, Selectica’s board was advised it was at risk. Selectica then announced on November 17, 2008 that it had implemented an NOL pill with a 4.99 percent threshold.

A month later, Versata began trying to “buy through” Selectica’s NOL pill, quickly bringing its ownership percentage up to 6.7 percent. A representative of Versata stated that the NOL pill was intentionally tripped in order to “bring accountability” to Selectica’s board and to “expose” the “illegal behavior” of Selectica in creating a poison pill with such a low threshold. Another representative stated that Versata wanted to “accelerate discussions” regarding the settlement money that Selectica still owed Versata. [19]

Selectica’s board offered to amend its NOL pill to exempt Versata from the adverse consequences of the pill if Versata entered into a standstill agreement. Versata refused, and, in early January 2009, Selectica exchanged each right under the NOL pill held by shareholders other than Versata for an additional share of Selectica stock as permitted under the pill, thereby doubling the number of shares held by all shareholders other than Versata and diluting Versata’s share holdings from 6.7 percent to 3.3 percent. Selectica then put a replacement NOL pill in place. This was the first time that a poison pill had been intentionally tripped and exercised.

The Chancery Court, applying the Unocal standard, found that Selectica’s directors reasonably believed that the NOLs had value and were worth protecting, and that allowing the NOL pill to be exercised was a reasonable response to Versata’s threat. [20]

On October 4, 2010, the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed the Chancery Court’s decision. [21] The Supreme Court noted that Selectica’s board conducted a lengthy analysis regarding the value of, and the risks to, the company’s NOLs. The board could reasonably have concluded that there was a real and significant threat that the NOLs could be impaired if no action was taken. The Supreme Court pointed to Selectica’s efforts to resolve the issue by offering Versata the option of not being diluted in return for entering into a standstill agreement. Versata’s refusal, together with evidence that could reasonably have led the board to conclude that Versata may have tried to cause an ownership change that would significantly devalue the NOLs, made it clear that exercising the NOL pill was a reasonable response.

The Supreme Court also found that setting the NOL pill’s threshold at 4.99 percent was appropriate because it was driven by the definition in Section 382 and not by an arbitrarily low level set by Selectica. The Supreme Court made it clear, however, that its decision in this case does not give license to all corporations that have (or do not have) NOLs to implement a poison pill with a 4.99 percent threshold. [22]

Protection of Corporate Culture: eBay v. Newmark (Craigslist)

On September 9, 2010, the Chancery Court issued its decision in eBay v. Newmark, in which the court for the first time reviewed the validity of a poison pill installed by a closely held company (the online classified ad service, Craigslist). [23] Interestingly, the threat that Craigslist identified was not that shareholders might be deprived of a reasonable control premium in a change of control transaction; instead, the concern seems to have been that Craigslist’s unique corporate culture, which is focused on serving the community rather than maximizing profits, might be destroyed—not now, but sometime in the future— if the heirs or estates of the two controlling shareholders decided to sell out to eBay or another corporate, profitmaximizing giant.

In late 2004, eBay entered into an investment agreement with Craig Newmark and James Buckmaster, the controlling shareholders of Craigslist. Under the arrangement, eBay became a 28.4 percent minority shareholder while retaining the right to compete with Craigslist. In the event that eBay did compete, however, it would lose many of its rights under the agreement and all rights of first refusal over any Craigslist shares would fall away. This meant that Newmark and Buckmaster would lose their rights of first refusal over the shares held by eBay.

On June 27, 2007, eBay launched Kijiji.com, an online classified ads site that directly competed with Craigslist. In response, Newmark and Buckmaster attempted to unwind the relationship with eBay, but eBay was not receptive to this idea and instead offered to buy the remainder of the shares of Craigslist. Concerned with the free transferability of eBay’s shares, Newmark and Buckmaster, without eBay’s approval, implemented three defensive measures. In addition to implementing a staggered board and offering to issue one new share of Craigslist stock for every five shares over which a shareholder granted Craigslist a right of first refusal, the company put in place a poison pill with a 15 percent threshold. As eBay held slightly less than 30 percent of the shares of Craigslist, the poison pill would make it impossible for eBay to transfer its shares in one block. eBay brought suit against Newmark and Buckmaster in the Chancery Court, alleging they had breached their fiduciary duties as directors and controlling shareholders of Craigslist.

The Chancery Court rescinded the poison pill. [24] In applying the Unocal standard to the adoption of the pill, the Chancery Court found that there was no reasonable risk that eBay could take control of Craigslist or even increase its holdings because Newmark and Buckmaster controlled all the remaining shares. As for Newmark’s and Buckmaster’s concerns over the future of Craigslist’s corporate culture, the Chancery Court found that the for-profit corporate form in which Craigslist operates “is not an appropriate vehicle for purely philanthropic ends, at least not when there are other stockholders interested in realizing a return on their investment.” [25] The Chancery Court instead found that Newmark and Buckmaster were punishing eBay for competing with Craigslist.

The Chancery Court upheld the staggered board under the business judgment rule, but rescinded the one-for-five share issuance measure as a violation of Newmark’s and Buckmaster’s fiduciary duties under the entire fairness standard.

Both the Craigslist and Selectica cases addressed relatively new uses of poison pills. In much more traditional uses of poison pills described in the next two examples, the Chancery Court demonstrated that, despite the hostility of many shareholders to their use, under Delaware law poison pills that are properly structured, adopted, and administered will generally be upheld by the courts.

Continued Legal Validity of Poison Pills: Yucaipa v. Riggio

On August 12, 2010, the Chancery Court issued its ruling in Yucaipa v. Riggio. [26] Investor Ronald Burkle, through his Yucaipa funds, sued Barnes and Noble (B&N), a publicly traded company, and its founder Leonard Riggio when B&N implemented a poison pill in response to Yucaipa’s rapid increase in its holdings of B&N stock.

In November 2008, Burkle bought an 8 percent share of B&N. Before doing so, he told Riggio, who held approximately 30 percent of B&N shares, that Yucaipa would be investing. Soon thereafter, Burkle and Riggio met to discuss the future of B&N and Yucaipa’s intentions. Burkle floated ideas about B&N’s potential future, including partnering with a technology company and purchasing some of Borders’ successful stores. Riggio felt that the purchase of stores from Borders would expose B&N to additional real estate holdings, which he felt was not a good strategy in light of the probable retail slowdown in 2009. Burkle agreed that Riggio’s position made sense.

In August 2009, B&N announced that it was going to acquire Barnes & Noble College Booksellers, an independent company that was owned by Riggio and his wife, for $596 million, and the transaction closed at the end of September 2009. Burkle was infuriated by this acquisition, in part because he felt it was inconsistent with Riggio’s prior statement regarding real estate exposure. Yucaipa then began to rapidly purchase B&N shares, having increased its holdings to 17.8 percent by mid-November 2009. Fearing that Yucaipa planned to take control of B&N, the B&N board adopted a poison pill with a 20 percent threshold. The pill would, however, allow Riggio to maintain his holdings of over 30 percent of B&N shares, but not to increase his holdings.

Yucaipa then sued, challenging the validity of the poison pill, arguing among other things that adopting the pill was outside a reasonable range of responses to any threat posed by Yucaipa, and that keeping the pill in place would prejudice Yucaipa in any proxy contest given the large block of shares controlled by Riggio and his allies.

Applying the Unocal standard, the Chancery Court found that B&N’s implementation of the poison pill was reasonable in light of the threat posed by Burkle, noting Yucaipa’s sudden accumulation of additional shares and other evidence that Burkle was exploring strategic options for B&N by meeting with investment bankers. [27] The Chancery Court also noted that Yucaipa would be able to prevail in a proxy contest despite holding slightly less than 20 percent of B&N’s common shares, a point Yucaipa ultimately conceded during post-trial argument. [28] The Chancery Court noted that Yucaipa’s director nominees would stand a good chance of succeeding in a proxy contest due to the likely support they would receive from ISS and other proxy advisory services. [29]

“Just Say No”: Air Products v. Airgas, Inc.

In one of the most closely followed takeover stories of the past year, the Delaware Court of Chancery addressed the question of whether a board of directors, consistent with its fiduciary responsibilities, may allow a poison pill to remain in place when it prevents informed shareholders of a target company subject to a non-coercive, all cash, fully financed tender offer from deciding for themselves whether to sell their shares into the offer. [30] In Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. v. Airgas, Inc., the Chancery Court upheld Airgas’ pill under Delaware Supreme Court precedent; promptly after the decision was handed down, Air Products ended its 16-month pursuit of Airgas.

Airgas had adopted its poison pill in May 2007. [31] Beginning in September 2009, Air Products made several private overtures to Airgas, but faced with repeated rebuffs from the Airgas board, Air Products eventually launched a tender offer for Airgas in February 2010. Air Products’ initial $60 per share tender offer was conditioned on Airgas redeeming its poison pill, among other things. After reviewing Airgas’ management’s five-year strategic plan and receiving inadequacy opinions from two investment banks, Airgas’ board recommended that its shareholders not tender their shares into the offer, concluding that the $60 per share offer grossly undervalued the company.

The board recommended against each subsequent increased offer made by Air Products over the following months, each time after careful consideration, finding each of them inadequate and ultimately asserting that Airgas was worth at a minimum $78 a share. Air Products also commenced and won a proxy campaign, electing to Airgas’ staggered board at the September 15, 2010 annual meeting a slate of three directors who would take a “fresh look” at Air Products’ offer.

Air Products also received enough support from shareholders at the 2010 annual meeting to advance Airgas’ 2011 annual meeting to January 2011. Air Products hoped to elect another three directors to Airgas’ staggered board in short order, thereby quickly taking control of the 10-member board. However, the Delaware Supreme Court invalidated this maneuver, and Air Products was forced either to persuade the courts to require the Airgas board to redeem the pill or wait another seven or eight months to seek to win control of Airgas’ board. [32]

While the Chancery Court was considering Air Products’ lawsuit, Air Products made its “best and final” $70 bid for Airgas. The Airgas board—this time including Air Products’ own nominees—unanimously rejected this offer too as inadequate. Presumably to Air Products’ surprise, its nominees—after being elected to the Airgas board, retaining separate counsel, and persuading Airgas to hire a third independent investment bank—were favorably impressed with Airgas’ management’s strategic plan and found the underlying assumptions to be reasonable.

On February 15, 2011, the Chancery Court, analyzing the case under the Unocal standard, found that the board’s decision not to redeem the poison pill was a reasonable response to the risk that the majority of shareholders would tender their shares for an inadequate price. The Chancery Court was persuaded that the board reasonably believed that Air Products’ “best and final” offer was inadequate, not only by the careful consideration given the offer by the Airgas board, the unanimous conclusion of the board that included Air Products’ three nominees, and the inadequacy opinions rendered by three investment banks, but also by the quality of the Airgas strategic plan. By all accounts, it was a detailed plan developed in the ordinary course of Airgas’ business well before the Air Products bid materialized, and had not been adjusted in response to the offer.

The Air Products nominees were favorably impressed not only by the plan and its assumptions, which they found were thoughtful and conservative, but also by how well the board understood the plan.

The Delaware Supreme Court has held that “substantive coercion” is a legally cognizable threat under Unocal. [33] Substantive coercion exists where a hostile bid is inadequate and there is a risk that shareholders will nonetheless sell into the inadequate offer either because they are ignorant of management’s analysis as to the underlying value of the company or because they misunderstand or disbelieve it. Here, the risk was slightly different, but no less of a legitimate threat: because a large number of Airgas’ shareholders were short-term speculators, they were likely to sell into Air Products’ inadequate offer in order to lock in a quick profit, regardless of the intrinsic adequacy of the price. The court went on to hold, citing the Versata case for the proposition that “the combination of a classified board and a rights plan do[es] not constitute a preclusive defense,” [34] and noting that Air Products could realistically win a second proxy contest, that Airgas’ defenses were not preclusive and were a reasonable response to the outstanding threat.

The case is an example of the continued vitality of the “just say no” defense in Delaware, at least under the right circumstances. Moreover, it underscores that in Delaware, directors are tasked with managing the affairs of a corporation—even in the realm of takeover defense —and directors can exercise their “managerial discretion, so long as they are found to be acting in good faith and in accordance with their fiduciary duties (after rigorous judicial fact finding and enhanced scrutiny of their defensive actions).” [35] But boards of Delaware corporations cannot always “just say no” in the face of hostile offers. “The Board does not now have unfettered discretion in refusing to redeem the rights.” [36] Critical to the Airgas court’s decision was the comprehensive, realistic, pre-existing strategic Airgas management plan that the Airgas board used to value the company, the views of Air Products’ own nominees that the offer was inadequate, and the thorough good faith efforts made by the Airgas board at every stage in the process. These factors are not likely to appear in all takeover contests.

Beneficial Ownership

An Example of Derivatives Included in a Definition of “Beneficial Ownership”

A Person shall be deemed the “Beneficial Owner” of, and shall be deemed to “beneficially own,” and shall be deemed to have “Beneficial Ownership” of any securities:

that are the subject of, or the reference securities for, or that underlie, any Derivative Interest of such Person or any of such Person’s Affiliates or Associates, with the number of Common Shares deemed Beneficially Owned being the notional or other number of Common Shares specified in the documentation evidencing the Derivative Interest as being subject to be acquired upon the exercise or settlement of the Derivative Interest or as the basis upon which the value or settlement amount of such Derivative Interest is to be calculated in whole or in part or, if no such number of Common Shares is specified in such documentation, as determined by the Board in its sole discretion to be the number of Common Shares to which the Derivative Interest relates.

“Derivative Interest” shall mean an interest in any derivative securities (as defined under Rule 16a-1 under the Exchange Act) that increase in value as the value of the underlying security increases, including, but not limited to, a long convertible security, a long call option and a short put option position, in each case, regardless of whether (x) such interest conveys any voting rights in such security, (y) such interest is required to be, or is capable of being, settled through delivery of such security or (z) transactions hedge the economic effect of such interest.

Source: Compellent Techs., Inc., Form 8-K, December 16, 2010.

One trend that could be interesting to watch in 2011 and beyond is whether companies are addressing concerns over the breadth of the “beneficial ownership” definition in poison pills. In 2010, only a handful of poison pills—21 of the approximately 900 pills outstanding at the end of the year—were amended or adopted with language intended to capture the panoply of derivative instruments that can confer voting control over, or the economic benefit of, shares to a person without actually placing the shares in the person’s hands. (See box at left for sample language.)

Despite some commentators’ and practitioners’ unease, most pills still do not include this derivative-driven language. One reason may be concern over the unintended consequences of untested wording. Does the language cover too much? Might it run afoul of the Unocal standard if its reach is too expansive? By being inadvertently too precise, could new developments in the derivatives markets (perhaps conceived specifically to work around the new language) be excluded from the definition? Another reason could be that it is not at all clear that the customary formulation is insufficient.

In the CSX Corp. v. The Children’s Investment Fund Management case, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York pointed to Rule 13d- 3(b) under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, a rule aimed at preventing arrangements that have the purpose or effect of circumventing the rules requiring reporting of beneficial ownership. [37] The court in that case found, given all the facts and circumstances, that the use of total return swaps conferred beneficial ownership of the notional shares on the activist hedge funds as a result of the application of Rule 13d-3(b). Since the concept of beneficial ownership in poison pills has been imported from the Exchange Act, many issuers may conclude that the concept imbedded in Rule 13d-3(b) will protect them against the use of instruments intended to get around the beneficial ownership definition.

It will be interesting to watch for changes in poison pill activity in 2011, as companies react to these recent prominent cases, as hedge funds get back into the activism game, and as M&A activity continues to grow.

The Conference Board Recommendations on Poison Pills

To avoid becoming a target of hostile takeover offers, The Conference Board recommends that corporate boards review their companies’ governance profile and address a number of specific issues.

- Consider drafting shareholder rights plans so that they satisfy standards of acceptability set by the most influential proxy voting advisors such as ISS, but also take into account that:

- As shown by the CSX case, investors may use certain types of derivative instruments to conceal their relative voting power. [38] Boards should consider whether their rights plans should be drafted to include derivative positions when computing the level of stock ownership a person holds.

- Net operating losses (NOLs) may not be able to be claimed for U.S. tax purposes if the corporation undergoes an “ownership change.” As shown in the Versata case, NOLs that can be claimed for tax purposes can be a valuable corporate asset. [39] If NOLs are threatened by an “ownership change” of the corporation (as defined in Section 382 of the Internal Revenue Code), e.g., change of more than 50 percent of the corporation’s stock over a rolling three-year period, it may be appropriate to implement a poison pill with a trigger below five percent (only shareholders of more than five percent are considered in the “ownership change” analysis). ISS recommends that these poison pills should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and expire at the earlier of the pills’ third year anniversary and the exhaustion of the NOLs.

- Consider having management maintain a thoughtful business plan for the corporation. As shown in the Airgas case, keeping a sensible, regularly updated business plan in place and making certain that the board understands and approves of the plan and its assumptions can be very important factors in defending against potential hostile takeovers. [40]

- Consider abstaining from certain defensive tactics, such as introducing supermajority voting requirements or disallowing action by written consent or limiting the ability to call special meetings, because they could cause the ire of ISS and attract activist shareholders.

- Consider adopting advance notice bylaws so that directors can avail themselves of enough time to obtain the information necessary to make a rational business decision about the acquisition or merger offer they have received. Establishing an advance notice requirement may comply with directors’ fiduciary obligations as it allows directors to avoid the pressure of a rushed business decision that could be detrimental to a long-term shareholder value creation strategy. Delaware judges have deemed even a 60-day advance notice provision as valid. [41]

Endnotes

[1] Air Prods. & Chems., Inc. v. Airgas, Inc., C.A. Nos. CIV.A. 5249-CC, CIV.A. 5256-CC, 2011 WL 519735 (Del.Ch. Feb 15, 2011).

(go back)

[2] Versata Enterprises v. Selectica, Inc., 5 A.3d 586 (Del. 2010).

(go back)

[3] eBay Domestic Holdings v. Newmark, C.A. No. 3705-CC, 2010 WL 3516473 (Del. Ch. Sept. 9, 2010).

(go back)

[4] See Matteo Tonello and Judit Torok, The 2010 Directors’ Compensation and Board Practices Report, The Conference Board, Research Report 1467, 2010, p. 45.

(go back)

[5] See Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum, 493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985).

(go back)

[6] John Laide, “A New Era in Poison Pills–Specific Purpose Poison Pills,” SharkRepellent.net (website), April 1, 2010 (www.sharkrepellent.net/request?an=dt.getPage&st=1&pg=/pub/rs_20100401.html&Specific_Purpose_Poison_Pills&rnd=372936).

(go back)

[7] Public reporting companies with poison pills in place, Capital IQ (website), retrieved January 4, 2011 (www.capitaliq.com).

(go back)

[8] Laide, “A New Era in Poison Pills – Specific Purpose Poison Pills.”

(go back)

[9] Ibid.

(go back)

[10] See 2008 U.S. Proxy Voting Guidelines Summary – ISS Governance Services, RiskMetrics Group, (Dec. 17, 2007), (www.riskmetrics.com/sites/default/files/2008PolicyUSSummaryGuidelines.pdf).

(go back)

[11] U.S. Corporate Governance Policy, 2010 Update, RiskMetrics Group (November 19, 2009) (www.riskmetrics.com/sites/default/files/RMG2010USPolicyUpdates.pdf). Note that ISS will consider new nominees for director positions on a case-by-case basis.

(go back)

[12] Takeover Defense Trend Analysis 2010 Year End Snapshot, FactSet Research Systems Inc., 2011 (www.sharkrepellent.com).

(go back)

[13] Takeover Defense Trend Analysis 2004 Year End Snapshot, FactSet Research Systems Inc., 2005 (www.sharkrepellent.com).

(go back)

[14] I.R.C. § 382 “Limitations on net operating loss carryforwards and certain built in losses following ownership change,” 2006.

(go back)

[15] Public reporting companies with poison pills with 5 percent triggers in place, Capital IQ (website), retrieved January 4, 2011 (www.capitaliq.com).

(go back)

[16] 2011 U.S. Proxy Voting Guidelines Summary, Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc., December 16, 2010 (www.issgovernance.com/files/ISS2011USPolicySummaryGuidelines20101216.pdf).

(go back)

[17] Versata Enterprises v. Selectica, Inc., 5 A.3d 586, at 607 (Del. 2010).

(go back)

[18] Ibid.

(go back)

[19] Versata, 5 A.3d at 596.

(go back)

[20] Selectica, Inc. v. Versata Enterprises, C.A. No. 4241-VCN, 2010 WL 703062, at 24–25 (Del. Ch. Feb. 26, 2010).

(go back)

[21] Versata, 5 A.3d at 607.

(go back)

[22] Ibid.

(go back)

[23] eBay Domestic Holdings v. Newmark, C.A. No. 3705-CC, 2010 WL 3516473 (Del. Ch. Sept. 9, 2010).

(go back)

[24] eBay Domestic Holdings v. Newmark, 2010 WL 3516473 at 24.

(go back)

[25] eBay, 2010 WL 3516473 at 23.

(go back)

[26] Yucaipa American Alliance Fund II, L.P. v. Riggio, 1 A.3d 310 (Del. Ch. 2010).

(go back)

[27] Yucaipa, 1 A.3d at 348.

(go back)

[28] Yucaipa, 1 A.3d at 354.

(go back)

[29] Yucaipa, 1 A.3d at 354–355.

(go back)

[30] Air Prods. & Chems., Inc. v. Airgas, Inc., C.A. Nos. CIV.A. 5249-CC, CIV.A. 5256-CC, 2011 WL 519735 (Del.Ch. Feb 15, 2011).

(go back)

[31] Air Prods. & Chems., Inc. v. Airgas, Inc., et al., C.A. 5249-CC (Del. Ch. December 23, 2010).

(go back)

[32] Airgas, Inc. v. Air Prods. & Chems., Inc., 8 A.3d 1182 (Del.2010).

(go back)

[33] Paramount Commc’ns, Inc. v. Time Inc., 571 A.2d 1140 at 1153 (Del.1990).

(go back)

[34] Air Prods. & Chems., Inc. v. Airgas, Inc., C.A. Nos. CIV.A. 5249-CC, CIV.A. 5256-CC, 2011 WL 519735 at 43 (Del.Ch. Feb 15, 2011) (quoting Selectica, 5 A.3d 586 at 604 (Del.2010)).

(go back)

[35] Air Prods., 2011 WL 519735 at 50.

(go back)

[36] Moran v. Household Int’l Inc., 500 A.2d 1346 at 1354 (Del. 1985).

(go back)

[37] CSX Corp. v. The Children’s Inv. Fund Mgmt. (UK) LLP, et al., 562 F. Supp. 2d 511 (S.D.N.Y. 2008).

(go back)

[38] CSX Corp., 562 F. Supp. 2d 511.

(go back)

[39] Versata Enterprises v. Selectica, Inc., 5 A.3d 586 (Del. 2010).

(go back)

[40] Air Prods. & Chems., Inc. v. Airgas, Inc., C.A. Nos. CIV.A. 5249-CC, CIV.A. 5256-CC, 2011 WL 519735 (Del.Ch. Feb 15, 2011).

(go back)

[41] See Nomad Acquisition Corp. v. Damon Corp., 1988 WL 3836667, at *8 (Del. Ch. Sept. 20, 1988).

(go back)

Print

Print