The following post comes to us from David Drake, President of Georgeson Inc., and is based on the Executive Summary of a Georgeson report. The complete publication is available here.

For many years, the proactive engagement of shareholders on corporate governance matters has been limited to just a handful of companies. However, over the past few years companies have shown a greater willingness to engage, particularly after the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (“Dodd-Frank”) made advisory votes on executive compensation (commonly referred to as “say-on-pay”) a mandatory voting item for most publicly traded U.S. companies. Last year we reported on the explosive growth in the level of engagement between public companies and investors on corporate governance matters, with both sides lauding the benefits of such engagement. Investors’ proxy departments have reported the benefits of gaining an early understanding of the issues a company is facing and the rationale behind decisions the company made beyond what is disclosed in the proxy statement. Meanwhile, issuers have found value in gaining firsthand knowledge of the nuances of investors’ proxy voting guidelines.

Given that both sides have seen the benefits of such an exchange, there has again been a significant rise in the number of engagement programs initiated by companies this year. As one would expect, there were a variety of reasons that companies sought to engage in outreach campaigns. While most companies engaged in order to improve on their past voting results, many others have aimed to establish a dialogue in order to maintain positive results. The scope of programs also tended to vary with many being quite expansive. These included lengthy off-season engagements with institutions, multiple contacts with the same institution during the year, in-person visits with investors and inclusion of members of the board of directors in the discussion. Some companies went so far as to proactively reach out to their top 100, 150 and even 200 institutional investors.

Whether it is the issue of mandatory say-on-pay, calls for majority voting in uncontested director elections or the systematic dismantling of takeover defenses, the fact remains that corporate issuers and shareholders may not always agree. Some may also continue to believe that this latest era of corporate governance reform has gone too far. Irrespective of one’s views on the topic, it seems clear that these most recent changes have ushered in a new era in corporate governance. This is an era marked by companies proactively seeking engagement opportunities with investors instead of viewing outreach as unnecessary. For a growing number of companies, discussions with investors have become an essential part of the annual meeting process and included among the “to do” list in preparation for proxy season. Simply put, this latest era can best be identified as “The Era of Engagement.”

Say-on-Pay Again Dominates the Proxy Agenda

For most companies, the 2013 proxy season marked the third year of say-on-pay votes, though the first for most “smaller reporting companies.” [1] [2] Since its inception, say-on-pay has easily been the major “hot-button” item in corporate governance and the most commonly discussed issue between issuers and investors. This focus on say-on-pay is not surprising because executive compensation is intrinsically complex. The board of directors strives to find the right compensation program to best ensure that the company is successfully addressing its specific business needs and maximizing shareholder value while also attracting and retaining qualified talent. Since each company has its own specific goals, strategy and unique set of business challenges, it is easy to understand why there is not a “one size fits all” approach to setting compensation. Along the same lines, investors’ approaches to evaluating compensation tend to vary as well, and understanding how each investor approaches evaluation is not always easy.

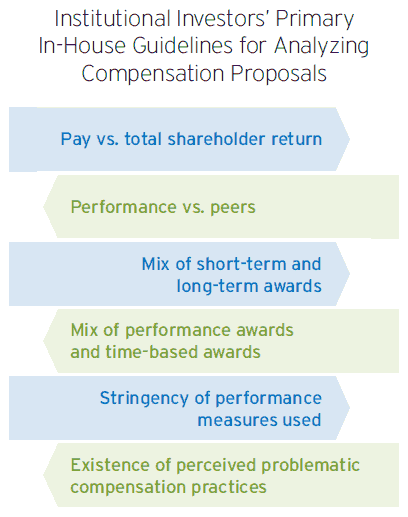

All institutions with mutual funds are required to make their “Policies and Procedures” for voting proxies available in the Statement of Additional Information addendum to the prospectus. Some will go further and post either the same guidelines or a more detailed version of the guidelines on their website. While the clarity of the guidelines provided varies by institution, most tend to be fairly vague. Most institutional investors have subscriptions to receive the proxy advisory reports of one or more of the major proxy advisory firms, ISS and Glass Lewis, though relatively few blindly follow these recommendations (a fact that comes as a surprise to many companies) and instead rely on the content of those reports to help to apply their own in-house proxy guidelines. For the majority of institutions that make decisions based on in-house guidelines, the analysis of compensation can vary greatly but commonly includes one or more of the following factors (among others): (i) pay vs. total shareholder return (on a one-year, three-year or five-year basis), (ii) performance compared to peers, (iii) the mix between short-term and long-term awards, (iv) the mix between performance awards and time-based awards, (v) the stringency of performance measures used, and (vi) the existence of perceived problematic compensation practices such as excise tax gross-ups or retention bonuses not tied to corporate performance. With hundreds of investors making proxy voting decisions based on varying factors, it is evident why companies choose to engage investors on this issue above all others.

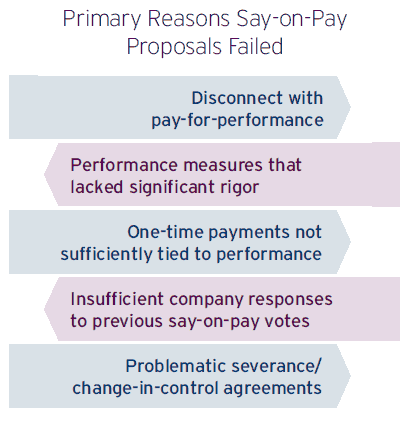

Voting results on say-on-pay showed slightly higher support levels in 2013, with proposals averaging 90.3% versus 88.6% during the same period in 2012. Of companies in the S&P Composite 1500 Index, a total of 22 companies failed to receive greater than a majority of votes cast in favor during the 2013 proxy season compared to 39 that failed their vote during the same period last year, a decline of over 42%. [3] However, among the broader market the results were not quite as divided: 47 companies in the Russell 3000 Index failed to receive a majority of votes cast on say-on-pay versus 51 during the same period in the previous year. [4] Within both groups, the reasons for failed proposals tended to vary but generally focused on a few areas: (i) a disconnect with pay-for-performance, (ii) performance measures that lacked significant rigor, (iii) one-time payments to executives that were not sufficiently tied to performance, (iv) insufficient company responses to previous say-on-pay votes and (v) problematic severance/change-in-control agreements.

Of the 22 failed say-on-pay votes in the S&P Composite 1500 Index, only seven were “repeat offenders” that had failed votes in 2012 and only four were companies that fell within the say-on- pay “red zone” last year (a term defined differently by different investors and proxy advisory firms but generally defined as proposals that, while passing, received a significant amount of against votes in the range of 20% to 25% of votes cast and, thus, likely to garner greater scrutiny in subsequent years). The remaining 10 failures [5] were all companies that garnered strong shareholder support in 2012.

Among the 14 companies that passed their shareholder vote in 2012 but then failed in 2013, the average decline in shareholder support was 50.9 percentage points. In contrast, 27 of the 39 companies that failed their say-on-pay votes in 2012 were able to get their proposals passed this year, [6] with 20 of the 27 receiving greater than 80% support and 15 companies receiving greater than 90% support. Interestingly, the average increase in shareholder support among the 27 companies that passed their proposal was 50.7 percentage points, nearly identical to the average decline discussed above.

The statistics above underscore a few key principles of which companies should be mindful. First, as we have mentioned in our previous two Annual Corporate Governance Reviews, past voting results are not necessarily indicative of future outcomes. Too often, companies are lulled into a false sense of security because previous voting results have been strong. What companies should understand is that shareholders’ analysis of say-on-pay proposals is largely dependent on corporate performance and a lag in performance may bring greater scrutiny to the underlying structure of a compensation program. If the program is then viewed as being overly generous to executives or not sufficiently rigorous to align pay with performance, shareholder support may drop and could even result in a failed say-on-pay vote. Second, a failed say-on-pay proposal in any one year should not be viewed as a “death sentence” from which companies are not able to recover. To the contrary, most companies were able to turn their votes around significantly, including a number of them with results in excess of 90% vote support. The reasons for these rebounds varied but generally included a combination of improved corporate performance and revisions to compensation programs to help better align executive pay with corporate performance, along with significant investor outreach to explain these changes. Finally, with several examples of dramatic declines in say-on-pay results,  companies are again urged to be mindful of their shareholders’ issues. Over the past few years, there have been a number of instances where warning signs were evident but companies either were not aware of the signs or did not act on them. For example, a management proposal that garners 80% to 85% shareholders’ support may be sufficient in most cases. However, in the case of say-on-pay it may instead be an early warning that shareholders may not be entirely satisfied with the existing program. Companies are advised to read the reports issued by the various proxy advisory firms as they tend to point out areas of potential concern (in 2013, ISS went so far as to provide FOR recommendations “with concern” for some companies). Additionally, companies are urged to engage with their shareholders and get to know their voting tendencies and address any concerns ahead of time.

companies are again urged to be mindful of their shareholders’ issues. Over the past few years, there have been a number of instances where warning signs were evident but companies either were not aware of the signs or did not act on them. For example, a management proposal that garners 80% to 85% shareholders’ support may be sufficient in most cases. However, in the case of say-on-pay it may instead be an early warning that shareholders may not be entirely satisfied with the existing program. Companies are advised to read the reports issued by the various proxy advisory firms as they tend to point out areas of potential concern (in 2013, ISS went so far as to provide FOR recommendations “with concern” for some companies). Additionally, companies are urged to engage with their shareholders and get to know their voting tendencies and address any concerns ahead of time.

Focus on Majority Voting Standard Shifts to Small-Cap Companies

Throughout the mid-2000s, the push by shareholder activists for companies to adopt majority voting in uncontested director elections (“majority voting”) dominated the proxy agenda. Between 2004 and 2007, our Annual Corporate Governance Review tracked nearly 200 shareholder proposals on the topic, including 87 proposals in 2006, when the proposal reached its peak. Over time, hundreds of companies have moved away from the default standard of plurality voting and adopted majority voting, particularly among large-cap companies. In 2010, as the U.S. financial system teetered on the brink of collapse and Congress debated the need for an overhaul of bank regulations, there were calls for another round of widespread reforms for public companies. Mandating majority voting was mentioned as a measure that should be included in any sweeping reform efforts, but as the final rules were written and Dodd-Frank was signed into law, majority voting was ultimately left out, leaving public companies to work within the current system of companies making decisions on an individualized basis (referred to as “private ordering”) and shareholder proponents to lament about the “issue that got away.”

There has recently been an effort by the Council of Institutional Investors (CII) to spotlight majority voting in the agenda of corporate governance reform. CII has spearheaded the public efforts by sending letters to the American Bar Association and Delaware State Bar Association in October 2012 and the New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ and Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) in June 2013. In its letters to the exchanges, CII requested that the exchanges mandate majority voting as a listing standard and require that “incumbent directors who do not receive a majority of votes promptly resign from the board.” [7] In addition to the more public efforts, various shareholder groups have worked behind the scenes to effect change by engaging with companies and strongly suggesting companies make the switch. These groups range from the more traditional activist investors, such as CalPERS and CalSTRS, to nontraditional activists such as fund managers, Vanguard, BlackRock and T. Rowe Price.

The CII’s letter to the exchanges cites the popularity of majority voting among large-cap companies but notes the drop-off in adoption among mid-cap and small-cap companies. In addition, the letter cites a report jointly issued by the IRRC Institute and GMI Ratings that details the relatively lower percentage of directors who actually resign from a company’s board after failing to receive greater than a majority of votes cast in favor (between 2010 and 2012, only 9% of directors resigned from boards). [8] The key points of the CII letter are generally accurate.

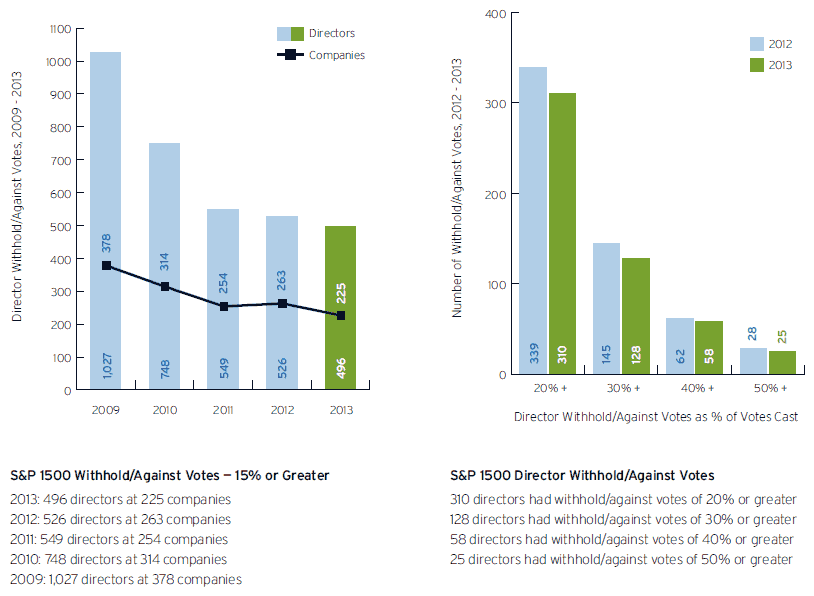

Although the percentages of smaller companies that have adopted majority voting increased over recent years, they lag behind larger companies. In fact, the percentages of companies in the S&P MidCap 400 and SmallCap 600 Indexes that have formally adopted majority voting via bylaw were 46% and 25%, respectively, versus the 80% of companies in the S&P 500 index that have adopted majority voting via a formal bylaw amendment. [9] Further, of the more than 8,700 director votes that Georgeson tracked during the 2013 proxy season, a total of 25 directors at 14 companies failed to receive greater than a majority of votes cast in favor of their election (down from 28 in the previous year). Of the 25 directors, eight were required to tender their resignation because the companies had adopted some form of majority voting. Of those eight, only one resignation has been accepted to date while one other chose to retire from the board following the vote. Of the remaining six, four resignations were not accepted by the board and another two companies had not yet reported on their decision.

There has been some debate about whether majority voting has sufficient “teeth” to promote proper accountability. Shareholder advocates, including CII, believe that allowing boards the latitude to retain directors who fail to receive majority support undermines investor confidence. They believe that such directors are “rarely, if ever, retained for what many investors and other market participants might consider legitimate reasons.” [10] While it is true that few director resignations are accepted, opponents of this view will argue that trying to measure the impact of majority voting by counting the number of resignations that are accepted or rejected is shortsighted and does not take into account the full impact majority voting has made. Between 2004 and 2008, when the debate about the merits of majority voting was raging on, the number of directors who failed to receive majority votes steadily increased and reached its peak in 2009 when 79 directors failed to garner majority support. Since that time, and as more companies began to adopt majority voting, many companies made changes to address issues that often result in lower shareholder support. These issues include (i) affiliated insiders sitting on key board committees, (ii) attendance issues, (iii) perceived egregious compensation practices and (iv) lack of board responsiveness to majority-supported shareholder proposals. As mentioned earlier, the number of directors who failed to receive majority support was 25, which is the lowest level we have seen in the past five years and nearly 70% of the 2009 peak. In addition to the decrease in failed elections, opponents will point to the unspoken impact that majority voting has had beyond what form of majority voting has been adopted. Over the past few years, as corporate governance has grown in prominence, companies have focused greater attention on maintaining best practices and directors have paid greater attention to the level of support they are receiving from shareholders. This was no more apparent than when two directors at both J.P. Morgan and Hewlett-Packard decided to retire or resign from their respective boards after their annual meetings. Though few directly attributed their resignations to the shareholder vote, some suspect that the decisions to leave the board were at least partly a result of the low shareholder support at the annual meetings (each of the directors received greater than a majority vote but fewer than 60% of votes cast in favor).

It will be interesting to see how the majority voting debate evolves from here. To date, there has been no response from the exchanges regarding the CII letter, and it is unclear whether any response will be forthcoming soon. In the meantime, shareholder proposals on majority voting continue to garner strong shareholder support. During the 2013 proxy season, 20 shareholder proposals on majority voting were submitted to a vote. The proposals averaged 59% percent of votes cast in favor, including 11 that received majority support. Interestingly, despite concerns that smaller companies were not paying sufficient attention to majority voting, only seven of the 20 proposals that came to a vote were on the ballot of a mid-cap or small-cap company. Our expectation is that smaller companies will continue to adopt majority voting at a comparatively slower rate than large ones. However, as the trend of shareholder proposals gradually shifts away from large-cap companies and moves more toward mid-cap and small-cap companies, we will see adoption rates increase.

Proxy Access Makes a Light Appearance

The debate regarding shareholders’ ability to remove seemingly ineffective directors goes beyond majority voting. Proxy access, the process by which shareholders would be allowed to submit nominees and have those nominees included in management’s proxy statement and on management’s proxy card (purportedly saving investors thousands of dollars in proxy drafting, mailing and printing costs), has been a topic of interest for shareholder activists for years. Since 2011, when the U.S. Court of Appeals vacated the SEC’s attempt at a federally mandated proxy access rule under Rule 14a-11, which would have permitted qualifying shareholders (or group of shareholders) who own at least 3% including three that received majority support. This year, the number of shareholder proposals appearing on ballots nearly doubled, with 11 proposals coming to a vote of shareholders, but the overall number of targeted companies remains lower than may have been expected.

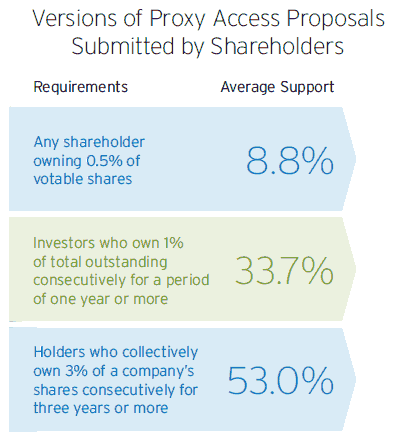

This year, there were three versions of the shareholder proposal submitted and voting results varied by which version of the proposal the company received. The first group of proposals was submitted by a group of individual investors and sought proxy access rights for any group of shareholders owning 0.5% of the company’s votable shares. The proposals appeared on four ballots and received the lowest level of support, averaging 8.8% of votes cast in favor. The second group of proposals was submitted by Norges Bank Investment Management to three companies. It is interesting to note that Norges chose not to submit binding bylaw proposals as it had done last year but once again sought proxy access rights for investors who own 1% of the total outstanding consecutively for a period of one year or more. The Norges proposal fared better than the individual investor group, averaging 33.7% of votes cast in favor. The final group of proposals submitted by a few different investors, including the New York City pension funds, mirrored the SEC’s requirements under Rule 14a-11, requesting proxy access rights for holders who collectively own 3% of a company’s shares consecutively for a period of three years or more. These proposals fared the best, averaging 53% of votes cast in favor, including majority support at three of the four companies where they were submitted.

In addition to the 11 shareholder proposals, two companies, Hewlett-Packard Company and Chesapeake Energy Corporation, chose to include management proposals to allow shareholder proxy access rights, making them the first to try and adopt proxy access via shareholder vote (a few others, including Western Union, have chosen to adopt proxy access via bylaw amendment without a shareholder vote). Each chose to offer the right with 3% and three-year holding requirements and each required greater than 66 2/3% of the outstanding shares supporting the proposal for adoption. One difference between the proposals is that Chesapeake Energy’s proposal would allow shareholders to nominate directors for up to 25% of the board while Hewlett- Packard’s would allow just 20%. In reviewing the results, the Hewlett-Packard proposal received sufficient support for adoption but the Chesapeake Energy proposal did not. It will be interesting to see how shareholders react to companies like Hewlett-Packard and Western Union in two ways. First, now that shareholders have the right to proxy access, it remains an open question as to whether they will seek to exercise that right immediately. As has been reported previously, various groups have worked to establish databases of prospective directors so the prospect for nominations does exist. Second, in light of the 35 and three-year holding requirements, it will be interesting to see whether activists will target these firms with shareholder proposals seeking lower thresholds and, if so, the reaction of other shareholders to any such resolutions.

Proxy Contest Activity on the Rise

After several years of steady decline, shareholder activism is once again on the rise. Through September 2013, the number of companies targeted for proxy contests this year rose to 79 versus 62 during the same period in 2012, an increase of 27%. [11] Additionally, the number of instances where dissident investors filed definitive proxy material numbered 37, up from 34 during the same period in 2012 and 20 in 2011. In terms of results, it appears that shareholders are continuing to win their fair share. Of the 37 contests we tracked, over one-third were either settled or withdrawn ahead of a shareholder vote, with many companies agreeing to add one or more dissident directors or making concessions to shareholders. Of those that actually came to a vote, dissidents were able to gain at least partial representation in 10 contests while incumbents won nine contests. At the time of this writing, five contests were still pending.

The increase in proxy contest activity is notable for a few reasons. First, in the wake of the market downturn, proxy contest activity nearly collapsed. Hedge funds, the primary driver behind proxy contests, were forced to change course as shareholders sought redemptions to protect their investments. As the markets have turned upward, hedge funds seem to have stemmed the tide of attrition and are in fact getting bigger, with reports of over $65 billion being invested in activist funds. In fact, as we review the proxy contests that progressed to a point where definitive proxy material was filed by a dissident, nearly all were brought forward by hedge funds seeking board representation. The second point of interest about proxy contests in 2013 relates to the types of companies targeted. According to a report by research provider Sharkrepellent, the number of targeted companies with a market capitalization of $1 billion or greater was 23 versus 16 during the same period in 2012, an increase of over 40%. [12] Targets have included Microsoft, Apple, and PepsiCo, all of whom are so large that only hedge funds with the deepest of pockets could ever realistically think of successfully targeting them.

The increase in shareholder activism was not limited to just proxy contests; investors targeted the M&A arena as well. In the past year, there were a number of high-profile transactions that were challenged by investors. An offer by Michael Dell and Silver Lake Partners to take Dell Inc. private was challenged by investors such as Carl Icahn and Southeastern Asset Management, who argued that the premium offered was inadequate. The Michael Dell-led group was ultimately successful in acquiring Dell Inc., but only after they agreed to a bump in the offer price and to pay a special dividend to holders. Sprint Nextel Corporation found itself in the midst of a prolonged period of contested transactions in its three- way merger with Clearwire Corp. and Softbank Corp. Beginning in late 2012, Sprint Nextel sought to acquire the remaining 50 percent of shares that it did not already own in Clearwire Corp while also selling a 70 percent stake of its own company to Tokyo-based Softbank Corp. The transactions were challenged by Dish Networks Corp., which attempted to halt the transactions by making bids for both Clearwire and Sprint. Sprint and Softbank were successful in completing their transactions but only after agreeing to increase the consideration in both cases. Softbank agreed to increase its payout to the shareholders of Sprint Nextel by $1.48 per share while also increasing the overall consideration by $1.5 billion dollars. Meanwhile, to fend off multiple overtures from Dish Networks, Sprint Nextel nearly doubled its offer for Clearwire from an initial bid of $2.97 per share to a final price of $5.00 per share. Ohio-based The Timken Company faced its own version of shareholder activism in what may be a new form of quasi-proxy contests. Included within the company’s proxy statement was a shareholder proposal submitted by CalSTRS, the California-based pension manager, requesting that the company spin off its steel business. Activist firm Relational Investors championed the cause and sought support for the proposal as if it were a proxy contest. Despite the fact that the shareholder proposal was presented as a non-binding (precatory) item, the board of directors decided to take action after the proposal received majority support and recently announced that it would spin off its steel business.

The rise in shareholder activism should serve as a point of caution for companies. Regardless of how big the organization or how strong past performance has been, investors are willing to advocate for change if they believe a company is underperforming. Thus, companies are urged to stay vigilant and take the time to assess their vulnerabilities and potential risk for a proxy contest. If a company has lagging performance or potential valuation issues, it should be taking steps to best address them and clearly articulate those plans to investors. From a governance perspective, a self-assessment of potential flaws in governance structures should be undertaken, including any gaps in board composition. Oftentimes, hedge funds will look for a “hook” or “toehold” when trying to push for change and use perceived governance flaws as that hook. Companies should closely monitor their shareholder base for any new, unknown investors or swings in shareholder composition. Finally, companies are urged to be proactive in creating a proxy contest “team” that they can rely upon in the event of a threat. The team should include experienced outside counsel, proxy solicitor and public relations firms, as well as bankers if circumstances dictate. By identifying the team early, companies can avoid the issue of scrambling to catch up in a crisis situation.

Endnotes:

[1] Smaller Reporting Companies defined as those companies with a market capitalization of $75 million and less.

(go back)

[2] Dodd-Frank required Smaller Reporting Companies that hold annual meetings on or after January 21, 2013, to include say-on-pay on their proxy voting ballot.

(go back)

[3] For purposes of this review, Georgeson includes abstention in its calculation of votes cast. For more information, please refer to the Methodology contained in the full publication.

(go back)

[4] Data Source: ISS Corporate Services.

(go back)

[5] One company, Digital Generation, Inc., did not hold an annual meeting in 2012.

(go back)

[6] Two of the 39 companies were acquired prior to their next annual meeting and three had not held their say-on-pay vote by the time this Review was written.

(go back)

[7] Letter from Mr. Jeff Mahoney, General Counsel, Council of Institutional Investors, to Mr. Edward Knight, Executive Vice President & General Counsel, NASDAQ OMX (June 20, 2013).

(go back)

[8] IRRC Institute & GMI Ratings, The Election of Corporate Directors: What Happens When Shareowners Withhold a Majority of Votes from Director Nominees? (August 2012).

(go back)

[9] Data Source: Factset Sharkrepellent.

(go back)

[10] Letter from Mr. Jeff Mahoney, General Counsel, Council of Institutional Investors, to Mr. Edward Knight, Executive Vice President & General Counsel, NASDAQ OMX (June 20, 2013).

(go back)

[11] Data Source: Factset Sharkrepellent.

(go back)

[12] Data Source: Factset Sharkrepellent.

(go back)

Print

Print