The following post comes to us from Mark Nadler, Principal and co-founder of Nadler Advisory Services, and is based on a Nadler white paper.

Picture, if you will, the chief executive officer of a Fortune 500 company slumped over a conference table, holding his head in his hands, anguishing over whether the time had come to pull the plug on one of his most senior executives. “Tell me,” he asks in despair, “is it this hard for everybody?”

Yes, it is.

Of all the complex, sensitive, and stressful issues that confront CEOs, none consumes as much time, generates as much angst, or extracts such a high personal toll as dealing with executive team members who are just not working out. Billion-dollar acquisitions, huge strategic shifts, even decisions to eliminate thousands of jobs—all pale in comparison with the anxiety most CEOs experience when it comes to deciding the fate of their direct reports.

To be sure, there are exceptions. Every once in a while, an executive fouls up so dramatically or is so woefully incompetent that the CEO’s course of action is clear. However, that’s rarely the case. More typically, these situations slowly escalate. Early warning signs are either dismissed or overlooked, and by the time the problem starts reaching crisis proportions, the CEO has become deeply invested in making things work. He or she procrastinates, grasping at one flawed excuse after another. Meanwhile, the cost of inaction mounts daily, exacted in poor leadership and lost opportunities.

This issue is so critical because it is so common. Embedded in the unique composition and roles of the executive team are the seeds of failure; it’s virtually guaranteed that over time, a substantial number of the CEO’s direct reports will fall by the wayside. The stark truth, as David Kearns of Xerox once remarked, is that the majority of executive careers end in disappointment. Nowhere is Kearns’s observation more poignant than at the executive team level. Of all the ambitious young managers who yearn to become CEOs, only a fraction will achieve their ultimate dream. Even among the relative handful who achieve the second tier, only a few possess the rare combination of intelligence, competence, savvy, flexibility, and luck to go out on top. The pyramid is steep and slippery; the closer you get to the top, the harder it is to hold on.

There are lots of ways for senior executives to stumble, and when they do, the shock waves can rock the enterprise. At the most senior level, each executive’s performance is magnified; one dysfunctional individual can stop the entire executive team in its tracks and wreak havoc throughout the organization. Consequently, decisions about replacing executive team members are highly leveraged, with far-reaching consequences often involving thousands of people and literally billions of dollars.

Despite those organizational consequences, the decision by any CEO to remove a direct report is, in the end, an intensely personal one. This isn’t a matter of reasoning your way through a strategic problem or even of deciding to lay off multitudes of workers halfway around the globe. Instead, it involves the face-to-face acknowledgment of failure by a powerful, successful member of the inner circle, quite possibly a long-time colleague. There is no way to take the pain out of these decisions; instead, our intent here is to suggest ways to make them somewhat more rational. There are processes and techniques that can help CEOs deal with executives who are in deep trouble, and methods to sort through the conflicting considerations that inevitably muddle the final decision. When the time comes to actually dismiss someone, however, there are no slick approaches or decision trees that can substitute for character and courage.

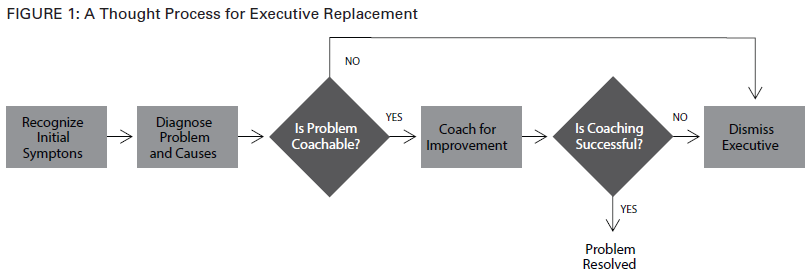

The process typically plays out along these lines (see Figure 1). At some point, the CEO recognizes there is a serious problem with a direct report. These problems come in all shapes and sizes, and we will describe some of the common warning signs that indicate something is seriously amiss. But these signs are merely symptoms. The next step is for the CEO, either alone or with help, to dig deeper to uncover the real source of the problem, and we will suggest a diagnostic framework to help with that process. Eventually, the CEO reaches the first fork in the road: deciding whether the executive’s problems are fatal or coachable. If coaching proves successful, that’s fine. If not, then the CEO faces the ultimate decision. We will detail some of the specific reasons CEOs give for putting off their decision, and then explain why those reasons are rarely as compelling as they might seem. Finally, we’ll offer some thoughts on things to keep in mind while performing the deed and ways to reduce the chances of encountering similar crises in the future.

Executive Teams and the Seeds of Failure

Our approach is grounded in some basic notions concerning the complexity of senior-level jobs and the profound consequences that can result from deficient performance at the top. Experience and observation lead us to this troubling but inescapable conclusion: The composition of the executive team virtually guarantees that some of its members will fail.

Each member of the executive team is required to play multiple, complex, and essential roles—and what’s more, to play them in concert with the CEO and with each other. That’s why it’s so difficult, and so crucial, to create and maintain an effective cast of senior characters. Basically, each member is expected to play these roles:

- Individual contributor, providing specialized analysis, perspectives, and technical expertise to the rest of the team

- Organizational leader, managing the performance of a major segment of the enterprise and representing that segment’s interests in the corporate setting

- Supporter of the CEO, promulgating the CEO’s agenda both publicly and privately

- Colleague and peer, demonstrating public and private support for fellow members of the executive team

- Executive team member, taking an active and appropriate role in the team’s collective work

- External representative of the team and the organization to the workforce at large and to outside constituencies

- Potential successor to the CEO or a potential member of the next generation of top-tier leadership

With each team member playing so many vital roles, just one ineffective, unqualified, or disruptive member can undermine the team and damage the organization in countless ways. The consequences can range from an impotent executive team to the breakdown of a key operating unit to the alienation of essential customers. Within the organization, the perceived tolerance of a senior executive who fails to meet objectives or openly flouts the organization’s values creates a huge credibility problem for management in general, and for the CEO in particular.

In reality, the odds are heavily stacked against CEOs as they try to create effective executive teams. The equation simply involves too many variables. It would be hard enough if all you had to do was find a group of people, each with the competence and capacity to satisfactorily fill all seven roles. But that’s just the beginning. The team’s success requires both balance and chemistry: the right balance of skills and expertise, and the right mix of styles, personalities, and relationships. To further complicate things, the balance and chemistry must also be consistent with the CEO’s strategic agenda and personal leadership style.

The Realities of Staffing

That’s a lot to ask. If you, as the CEO, were starting out in a perfect world—with a clean slate, an endless pool of qualified candidates, and all the information you wanted about each of them—then you just might have a chance of assembling the perfect team. But you don’t; no CEO does. And even if you could put together the all-time executive all-star team, it would only be a matter of time before the shifting dynamics of the situation—changes in your strategic environment as well as evolving relationships within the team—would throw the equation out of kilter.

In reality, the unique circumstances that shape the composition of executive teams invariably lead to considerable turnover. If you look at practically any executive team, you’ll find members who, through no fault of their own nor that of anyone else, fit into at least one of these high-risk categories:

Holdovers

Unless they’re staffing a start-up or arriving on the heels of a massive housecleaning, most newly appointed CEOs inherit all or most of their predecessors’ direct reports. That’s a problem, since every CEO wants the chance to form a team to fit his or her own agenda, priorities, personality, and leadership style. It’s naïve to expect the old team to remain intact; on the contrary, it’s much more reasonable to assume that most holdovers are living on borrowed time.

Overachievers

Because executive team roles are so unique, past performance in other positions becomes a peculiarly unreliable predictor of future performance. Time after time, people who have distinguished themselves in jobs just below the executive team level are bewildered and overwhelmed by the complexities, nuances, and conflicting demands of their new senior positions. Tossed into the fray, some people quickly demonstrate that they have been promoted past their level of optimal performance. It’s not a matter of needing more time, experience, or coaching; they just don’t have what it takes.

Tryouts

If all your executive team slots were filled by safe, senior people with extensive track records, then you, as CEO, would be failing in your responsibility to develop the next generation of leadership. In the interests of long-term succession management, CEOs must sometimes give the most promising members of the next generation the chance to grow and prove themselves in the big leagues. That means some people will join the team with the clear understanding that they are not going to walk in on Day One as fully functioning members of the team. It also means that some appointments are deliberate gambles: Tryouts, by definition, imply that some candidates won’t make the cut.

Outsiders

In one company after another you hear the same complaint: “We’ve got plenty of good managers but very few who are ready for the top jobs.”

The accelerating pace of change, relentless competitive pressures, and the growing complexity of senior jobs all exacerbate the problem of insufficient bench strength. As a result, more and more organizations are recruiting executives from the outside. That’s understandable; typically, outsiders bring new skills, knowledge, mindsets, and ideas about culture. However, outside hires are far riskier than internal promotions. For a host of reasons—inadequate information, less-than-candid references, the highly polished interview skills normally exhibited by senior executives—buyers can never really be sure what they’re getting.

It usually takes from 12–18 months on the job before a senior-level hire can be accurately assessed. By that time, according to our tracking of hires at several large corporations, it’s likely that no more than 25–30 percent will have lived up to initial expectations, 30 percent will fall short but be good enough to retain in some capacity, and roughly 40 percent should be shown the door.

Dinosaurs

Some executives are perfectly adequate until things change—and they can’t change with them. In nearly every episode of large-scale change, there are executive team members who are smart, capable, and competent but who, for one reason or another, just can’t succeed in the new environment. Some violently disagree with the direction of the change. Some find it impossible to change their management style. Some wrestle unsuccessfully with new structures and processes. And some, whose performance was acceptable in the past, simply lack the higher gear required to meet more demanding requirements. For whatever reason, organizational change nearly always results in executive team change.

It’s critical for CEOs to understand that when it comes to staffing executive teams, there is no zero-defect model—some people just won’t work out. Moreover, attempts at error-free staffing are tantamount to staffing in error; safe choices preclude the possibility of standouts and diminish the opportunities for future leaders.

It’s also important to remember that executive team members are hardly innocent victims who were forced into their jobs at gunpoint. Most have eagerly sought advancement; by this point in their careers, they should be well aware of the risks they’ll encounter when they make the climb to the high wire. Yet, time and again, people become prisoners of their own ambition and oversell themselves. The harsh truth is that we each share in the responsibility for our own career development.

So CEOs need to differentiate for themselves between their own staffing mistakes and mismatches rooted in circumstance. As we will discuss shortly, it’s essential that CEOs confront their personal feelings about these instances of failure; otherwise, every failure, no matter what its cause, becomes a source of debilitating guilt.

Recognition: Understanding the Warning Signs

Let’s be candid: Few senior executives perform their jobs flawlessly. Considering the inherent complexity of these jobs, it’s foolish to think that every executive will perform each of the distinct roles with equal grace and skill. Ideally, each member is recruited to the team because of the special ingredients he or she will add to the mix; presumably, each person’s strengths will lie in different areas.

The first hard decision for the CEO is to differentiate between normal weaknesses and potentially fatal flaws. At some point, the CEO becomes plagued by the recurring question: Is this person going to work out, or should I start thinking about a replacement? While there are no pat answers, there certainly are warning signs that should alert the CEO that it’s time to move beyond idle speculation. These include:

- Performance. Start with the basics. Is the executive in question getting the job done? Are his or her units achieving their goals? Are responsibilities being met? Is the executive demonstrating the managerial skills and technical expertise the job requires?

- Internal consistency. Is this executive meeting the goals they set for themselves? It’s one thing to argue that imposed goals are unrealistic; it’s quite another to fall short of what you came up with yourself.

- Shifting the blame. Generally, you can assume you have a serious problem if executives start blaming everything on forces beyond their control—the sagging economy, wily competitors, fickle customers, undependable suppliers, uncooperative colleagues, surly employees.

- Denial. If executives keep insisting they are going to make their numbers despite all indications to the contrary, you have something to worry about. The same goes for a refusal to acknowledge the existence of readily apparent problems in relationships—with the CEO, with peers, or with subordinates.

- Signals from peers. The members of the executive team generally know when one of their peers is fouling up. Yet in most organizations, the prevailing culture discourages them from openly criticizing a colleague. A CEO who suspects there is a problem should start watching for subtle messages in the language and behavior of the executive’s peers.

These warning signs can help. In the end, however, it inevitably comes down to a judgment call by the CEO. Like lots of major decisions—and more than most—this one comes from the gut. By this point in their careers, CEOs have probably developed some strong instincts about people, and it’s important to pay attention to those internal warning signs. Constantly waking up at 3 a.m. worrying about a particular executive is usually a good indication that something is wrong. Here’s another: Try doing a dry run on a scene in which you are explaining to an executive why he or she is being removed from the team. Sit down and write out the specific reasons you would give. The resulting insights can be powerful. “When I look at this list,” said one CEO, “I can’t believe I’ve been ignoring this for so long.” Some CEOs, while role-playing the scene, find themselves surprised by how “right” it feels.

Nevertheless, it’s rare for a CEO to decide at this early stage that a top executive is beyond help. More often, these red flags indicate situations that are headed downhill but haven’t yet reached bottom. Keep in mind, however, that waiting for conclusive evidence before taking action usually means waiting too long. Executive coaching tends to be a lengthy affair; the search for a replacement takes even longer. Consequently, a CEO who procrastinates until the situation is irreversible has probably squandered six months to a year of valuable time.

Diagnosis and Coaching

All the warning signs—the executive’s observable performance and the CEO’s personal apprehension— are merely symptoms. Before the CEO can rationally decide on the next step, it’s essential to diagnose the problem in order to determine where the real issue lies and whether there is any reasonable way to fix it.

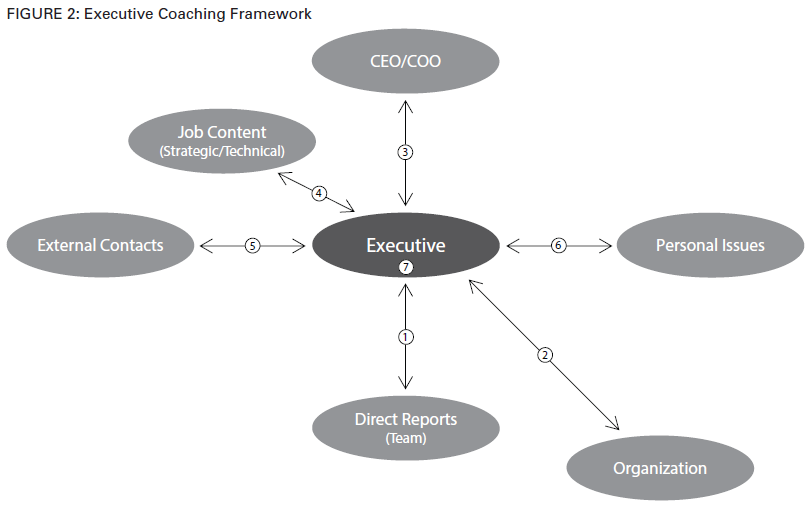

Moreover, assuming that the CEO’s strong preference is to provide the coaching and remediation that will help the troubled executive succeed, the starting point would be diagnosis. One way to begin is by assembling all the available information—both empirical and anecdotal—that describes the executive’s performance and behavior in these diagnostic areas (see Figure 2):

- The executive’s relationships with his or her own team of direct reports

- The executive’s effectiveness within the organization he or she leads

- The executive’s relationships with his or her immediate boss (the CEO or possibly the COO)

- The executive’s performance of the strategic and technical elements of the job

- The executive’s performance of external responsibilities toward customers, suppliers, the investment community, governmental agencies, etc.

- The executive’s personal issues, such as career goals, ambition, self-confidence, and family relationships

The object is to identify patterns of problems. Sometimes the diagnosis turns up “patterned inconsistencies”; for example, the executive’s relationships with subordinates are uniformly horrendous, but relationships with peers and bosses seem fine. Such patterns help indicate what kind of coaching might be productive. If the diagnosis is done well, the results will bring the CEO to the first major fork in the road. Sometimes the choice is clear—the executive’s fundamental problems may simply be uncoachable.

Here’s why: You can coach technique. You can coach certain behavioral patterns—how people deal with subordinates, for example, or how they operate within teams. You can coach technical expertise to a certain extent, and you can use coaching to bring someone up to speed on basic knowledge. But coaching has its limits. You cannot coach character, integrity, or basic intellectual capacity. You cannot coach a fundamental change in personality. And you cannot coach someone out of a pathology.

So at this juncture, the CEO faces two critical questions. First, the fork in the road: Does the diagnosis indicate that the executive’s problems are coachable? Second, what results can be expected from coaching, and over what period of time? In other words, what is the maximum return that can be expected on the investment of time, effort, and lost opportunities? Assuming the best possible coaching, how good can this person ultimately become—and is that result worth the time and effort it might take to get there?

These are tough questions. Unless the situation is a total disaster or the problems involve issues of integrity or intelligence that are clearly beyond coaching, the inclination at this point—as it probably should be in most cases—is that some period of coaching seems reasonable.

Coaching: Concepts and Techniques

It’s not our intent to present a comprehensive guide to executive coaching. There is substantial literature on the subject and plenty of resources available to any CEO who chooses to go that route. However, it’s worth noting several concepts and techniques we’ve found useful.

First, it’s helpful to go beyond the information collected during the initial diagnosis and to gather additional data pertaining specifically to the areas to be coached. Generally, that requires the personal involvement of the executive being coached, who needs to understand how critical his or her constructive involvement in the process will be. Peers, subordinates, and others with special insights into the executive’s performance and behavior should also be debriefed as the coaching proceeds.

Second, it’s worthwhile to specifically identify who will be responsible for active coaching. It might be the CEO, another executive, an outside resource, or some combination of all three. Whoever is involved should be in a position to observe the executive in actual working situations and provide immediate feedback and skill practice.

Third, the coaching has to include benchmarks and deadlines. At critical steps along the way, specific indicators must demonstrate how much progress is being made and how quickly. Coaching is like any other business process—it must include ways to measure progress and improvement.

Finally, it’s important for the CEO to involve the Board, for several reasons. It’s in the CEO’s interests to acknowledge a serious problem and the steps being taken to deal with it. Also, this group can sometimes be a helpful sounding board, and some directors might be in a position to provide some coaching. Lastly, by making a commitment to the Board that the matter will be resolved one way or another by a certain date, the CEO forces himself to stop procrastinating.

The Moment of Truth: Making the Tough Decision

Fortunately, coaching sometimes works. There are plenty of success stories, which is why coaching remains such an attractive and humane alternative to forcing executives out at the first sign of trouble. The bad news is that coaching sometimes fails; with each passing month, there is abundant evidence that progress is either elusive or so minimal as to erase any hopes of getting the executive up to the required speed by the established deadline.

Yet even in those instances, many CEOs will look for reasons to procrastinate—to ignore the deadlines and lower the bar—and some will go to practically any length to avoid dismissing a member of their team. There are several reasons why so many smart, capable chief executives will go to such extremes to avoid removing one of their direct reports:

Narcissism

CEOs typically possess an unusually high need to be loved, admired, and respected by everyone within their sphere of influence. That’s an important component of their personality and a big part of what drove them to become a CEO in the first place. For these people, face-to-face firings tend to be intensely uncomfortable—the recipient of a pink slip is unlikely to respond with love, admiration, and respect. These situations are particularly awkward for CEOs who have been promoted from within; just a short time ago, the person being fired might well have been a peer, a colleague, perhaps even a mentor. There is no getting around it; these are painful, sometimes devastating circumstances.

The Big Fall

The CEO is well aware that he or she is dealing with highly successful people who might never have experienced significant failure in their adult lives. The shock of that first failure, compounded by the stakes involved—money, security, professional reputation, career expectations—all heighten the probability that this will be a crushing blow to the executive, making the CEO even more reluctant to lower the boom. There is no way to ignore the consequences for the individual, but it is equally important to keep in mind, once again, that these are not innocent bystanders. The vast majority of executives at this level actively seek higher and higher positions, knowing that with each successive promotion both the benefits and risks increase proportionately.

The Failed Rescue

Many CEOs entertain savior fantasies—overblown and unrealistic notions of their own ability to change people and solve problems. They truly believe that skillful managers can help people improve. Perhaps, they wonder, if they had just given better guidance, stronger direction, and more effective coaching, none of this would have happened. Lying awake at night, the CEO starts to think, “If I can’t make this work, then maybe I’m really not as good as I think I am.” The truth is that any manager can do only so much. Executives are the product of years of personal and professional experiences that shape their personality, behavior, skills, and management style. For CEOs to think they can personally reverse years of training and experience in a relatively short time is not only unreasonable but, in the words of one CEO, “the height of arrogance.”

The Burden of Guilt

Beyond the coaching issue, CEOs sometimes feel immense guilt about the overall situation, blaming themselves for poor judgment in selecting the individual in the first place. Somehow they should have been sufficiently prescient to know the person would not work out. Now the executive has given up a good job and secure future with his old company, uprooted his family, turned his life upside down—and all for nothing. That scenario ignores several important considerations. First, the executive acted as a free agent, knowing in advance that any move to a new job or a new company invariably involves a certain degree of risk. Second, it implies that every appointment to the executive team should be a sure bet—a virtual impossibility, as we explained earlier.

The Rusty Sword

One of the benefits of being the CEO is that you can delegate some of the more distasteful chores to other people. That includes firings. After a while, CEOs simply get out of practice; the longer they go without actually dealing with dismissals face to face, the harder it becomes to contemplate doing it. But the unavoidable fact is that some executive responsibilities cannot be delegated, and dealing with dysfunction in the executive team is one of them.

Kremlin Watching

Forced departures from the executive team—even when cloaked in ambiguous, even misleading announcements—are highly visible and closely followed, both inside the organization and among concerned external constituencies. A single departure is a major event; two departures within a relatively short time suggest a trend, prompting people to speculate about instability and discord at the top of the organization. Before long, however, people realize that the world has not been turned upside down—no one is being shot in the parking lot at dawn, they still have the same job and the same boss they had last week—and things get back to normal. Moreover, the appointment of carefully selected replacements, accompanied by deliberately managed communications, sends powerful messages, both internally and externally, about how the organization is changing and about the style of behavior and level of performance that will be demanded of senior executives.

The Essential Link

CEOs are often concerned about the external consequences of senior-level dismissals or reassignments. Sometimes, executive team members cultivate close ties with customers, community leaders, the press, or the financial community and come to be viewed as essential links to the outside world. Fear of a backlash has prevented more than one CEO from replacing a problematic subordinate who was the darling of the stock analysts. It is not unusual to hear things like, “I know we should get rid of Tom, but the analysts would go crazy; he’s worth more than five dollars a share.” To be sure, these are justifiable concerns. Yet, somehow, large organizations always seem to weather the departure of these highly visible figures; generally speaking, the anticipation is far worse than the aftermath. The CEO has to keep in mind that outsiders see only a small part of the organization and the executive’s role in it, and are poorly positioned to weigh the executive’s overall value to the enterprise. Additionally, the CEO has to separate the reality of the executive’s outside influence from the exaggerated impressions some executives work so hard to create.

The Irreplaceable Cog

This is the internal version of the essential link. CEOs are extremely reluctant to remove certain executives who have become enshrouded in an aura of invincibility. People come to believe the place will grind to a halt without the special talents of these chosen few, who are thought to possess some particular technical expertise or a unique knowledge of “how things really get done.” Yet, except in all but a rare handful of cases, their talent or expertise is never as unique or as crucial as it seemed. In fact, it often turns out that the sales force or IT group or production operation runs better once the executive is removed and rational business processes replace a disorganized cult of personality.

The Incomplete File

The failure of coaching is a condition, not an event. Situations in which definitive evidence clearly demonstrates that an executive should be sacked are the exception rather than the rule. CEOs who keep hanging back, waiting for more and more information, will almost certainly wait too long. By the time that kind of information surfaces, the executive in question will have caused serious damage to the organization.

The Empty Bench

This is an all-too-common problem: As much as the CEO would like to get rid of someone, there is no obvious replacement in sight. Given the high stakes involved in putting the wrong person in the job, there is a tendency to hang on to the devil you know rather than gambling on the devil you don’t. Yet at some point, CEOs have to ask how long they, the team, and the organization can continue to tolerate inadequate performance or disruptive behavior.

We do not, by any means, underestimate the complexity of the choices faced by CEOs in such situations. Obviously, these are difficult decisions that must be undertaken soberly and with due deliberation. What we are suggesting, however, is that in the final analysis there are relatively few real limitations on the CEO’s capacity to act; by and large, the constraints are intensely personal and self-imposed. Moreover, the consequences of acting are rarely as dire as they seem at first glance; to the contrary, they often pale in comparison with the consequences of not acting.

A few years ago, one of our colleagues was working with the CEO of a major corporation who had put off for more than a year and a half the firing of a disruptive but highly influential member of his executive team. Finally, our colleague asked the CEO to pull out his checkbook and write a personal check for $10,000 as a wager that his subordinate would prove successful within six months.

“You must be crazy,” he responded.

“Why is it,” our colleague asked the CEO, “that you’re afraid to bet $10,000 of your own money that this guy is going to make it, but you’re willing to bet millions and millions of dollars of the shareholders’ money on the same thing? What are you seeing that makes you think, after all this time, that things are going to get better? Where are the signs of progress? What gives you that kind of confidence?”

There are always reasons to put off the decision: You need just a little more information, you want to wait for the results of one more quarter, you want to provide a little more time to develop a prospective replacement. Many CEOs have observed, in hindsight, that they came up with all kinds of rationalizations to put off a decision they knew was inevitable. In the end, all they succeeded in doing was hurting both the executive team and the organization while prolonging the agony of a stressed-out executive who was left twisting in the wind, awaiting his or her fate. In reality, the absence of a decision actually constitutes a de facto decision to keep tolerating an intolerable situation and to put off the inevitable process of finding a replacement.

Actions and Implications

Again, our intent here is not to provide a step-by-step manual on how to handle dismissals. However, certain actions and implications are particularly pertinent to removing people at the executive team level.

The first decision to be made is whether the executive to be replaced should be reassigned or removed. This is one of the issues that makes the executive team unique. Frequently, someone who’s not working out in a particular job can still contribute to the organization in a different assignment without facing public humiliation. It’s different when someone leaves the executive team: There’s nowhere to go but down or out.

The tendency is to assume that executives have to go. The typical metaphors can be fairly brutal, as in “never leave the wounded on the battlefield.” Yet there’s an undeniable logic to this view; given the personality of the executives involved and the circumstances leading to their removal from the executive team, the obvious next step may be to have them escorted out the door as quickly as possible. Relegating them to less prestigious positions, where they will seethe and become lightning rods for dissent, makes little sense.

Other cases, however, are much more difficult. Generally, CEOs think they are doing executives a favor by asking them to leave the company, saving them from the humiliation of accepting a lesser job. Yet some people prefer to stay. Many of those who fail at the top are feeling frustrated and perplexed because they are in so far over their heads. Although it might not be their first reaction, they are actually relieved when someone else makes the decision for them and removes them from the job they knew they couldn’t handle. And after they get over the initial shock and disappointment, they are perfectly happy to stay with the organization and do a lower level job that plays to their strengths. Rather than making assumptions, CEOs should give people sufficient time to clear their heads and consider their options.

A related issue is what we describe as the paradox of improved performance. Consider the case of a corporation whose vice chairman became totally obsessed with succeeding the chairman. Over time, he engaged in so much posturing and positioning that he became totally ineffective. Finally, the chairman sat him down, explained that things were not working out, and gave him six months to find another job. At that point, the vice chairman’s performance soared; he probably enjoyed the most productive six months he had ever experienced with the company. Had the CEO been wrong to fire him? No. As long as the vice chairman stayed with that company, he would have driven himself to go after the top job, and his dysfunctional behavior would have continued. As soon as he was freed from that obsession, he stopped playing games and just did his job.

That’s a common situation. People who have felt pressured, cornered, topped-out—whatever the source of their stress—instantly do better when relieved of the pressures inherent in their executive team positions. That doesn’t mean CEOs should reconsider their decisions or second-guess themselves; instead, it should be viewed as concrete evidence that these people were in the wrong job under the wrong set of circumstances.

The third issue is the need to carefully manage the communications surrounding the removal of an executive team member. This necessity has been complicated in recent years by the fear of litigation that could arise from any communications that are seen as harming someone’s reputation and limiting their career opportunities.

Unfortunately, fear of such litigation, compounded by common standards of corporate civility, has resulted in a tradition of dismissal announcements that completely obfuscate the real situation. Rarely is anyone fired; instead, executives leave “to pursue other interests.” In the absence of hard information people create their own fantasies—often involving dark conspiracies and shadowy motives—and reach their own conclusions about what really happened.

That’s a serious problem. It would be bad enough if senior management were merely missing the opportunity to send strong messages reinforcing corporate standards and expectations. Even worse is that in the absence of any information, people can easily construct bizarre scenarios that carry messages that are literally the opposite of what management wants to convey.

In the current litigious environment, management’s options are limited. One approach is to design communications that send implicit messages. Not everyone deserves a tearful send-off with the CEO’s sincere gratitude for years of faithful service and best wishes for future endeavors. These days, a terse message that someone is leaving—period—makes it clear to everyone that this executive is not floating away on the victory barge. Then, after obtaining legal advice as to what is permissible, the CEO should explain as much as possible to the executive team. That might seem obvious, but it’s amazing how common it is for senior executives to be left without a clue about why one of their colleagues has vanished. In too many organizations, it is a topic that is just not open to discussion.

Avoiding Future Crises

An executive dismissal usually gives rise to a good bit of soul-searching. The more reflective CEOs wonder, “How did this happen? Where did I go wrong? How did I let things get to this point? How can I avoid this happening again?”

Obviously, there are no guarantees of success at any level and certainly not at the top. For all the reasons we have discussed, it is inherently impossible to make foolproof appointments to the executive team or to think that once the right team is in place, all its members will continue to succeed until they become CEO or reach retirement age. Error-free staffing is not a realistic goal. Instead, the CEO should be looking for ways to deal with troubling situations long before they turn into full-blown crises.

Curiously, in one organization after another, the tools and techniques routinely used throughout the organization to monitor performance, identify problems early on, and take steps to rectify them just don’t seem to apply to the executive team. There appears to be an assumption that the CEO is so familiar with the team members and every aspect of their performance that there’s no need for the same assessment techniques that are required of every other manager and team leader in the organization. We have worked with companies where the members of the executive team—some of whom have been in their jobs for years—have never received a single formal performance review from the CEO.

The most obvious way to prevent serious situations from sneaking up is to make a commitment to continual assessment. There’s simply no substitute for it. The CEO has to employ a wide array of techniques—surveys, 360-degree feedback tools, outside consultants, frequent appraisals tied to specific objectives and deadlines—in order to stay on top of the situation. The work of senior executives is simply too important for poor performance to go unnoticed—and unaddressed—for any significant period of time.

Summary

Despite all the attention the press gives to “killer CEOs,” the truth is that when it comes to their own direct reports, most CEOs go out of their way to avoid forced removals. Don’t misunderstand: We’re not advocating ritual public executions just for the sake of showing stock analysts how tough you can be. To the contrary, we propose that CEOs look at executive team staffing from a realistic perspective that acknowledges the risks, the high probability of mismatches, the changing demands, and the shifting dynamics that are inherent in these unique teams. CEOs should understand that for the good of the organization, the team’s composition ought to keep changing over time; their role in making those changes is an integral part of their job, not an aberration.

Understanding all of these complexities is important—but it’s not enough. In the end, there is no substitute for managerial courage. The CEO, and only the CEO, is the one who must assess all the information, weigh the odds, objectively balance the interests of the individual against the demands of the enterprise, and then act—swiftly, humanely, and decisively.

Print

Print