Jeremy Berkowitz is Vice President in NERA’s Global Securities and Finance Practice. This post is based on a NERA publication authored by Dr. Berkowitz, Patrick E. Conroy, and Jordan Milev.

In July 2014, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted a package of reforms to the regulatory framework governing money market mutual funds. The SEC believes the new rules will enhance the safety and soundness of the money market fund industry during periods of market distress, when redemptions in some funds may increase substantially. [1]

The new rules require institutional prime (general purpose) and institutional municipal money market mutual funds to price and transact at a “floating” net asset value (NAV), permit certain money market mutual funds to charge liquidity fees, and allow the use of redemption gates to temporarily halt withdrawals during periods of stress.

Even before these changes take effect, the money market reforms require increased liquidity disclosures and enhance the stress testing requirements that have been in the rule since 2010. In the coming months, as money market funds gear toward meeting these requirements, it is increasingly important to be aware of the types of scenarios that the enhanced, SEC-mandated stress tests include and the appropriate econometric and data simulation framework that these funds would need to adopt—with board oversight—in order to meet SEC’s requirements. In this article, we demonstrate this framework and evaluate the results from running prescribed stress scenarios for a stylized money market fund to assist funds, their managers, and boards in preparing to implement the rule.

Background

In 2008, a large money market mutual fund known as the Reserve Primary Fund was forced to “break the buck” and lower its NAV per share below $1. The incident, an extreme rarity in modern money market fund management, was largely attributed to the Reserve Primary Fund’s exposure to the debt securities of Lehman Brothers. Breaking the buck triggered a run on the fund and caused heavy redemptions in other prime money funds, many of which did not have exposure to Lehman debt. [2] The Reserve Primary Fund froze withdrawals for up to seven days. When even this delay did not alleviate the liquidity crunch, the fund suspended operations and litigation ensued.

In response, the US Treasury initiated an emergency program, which guaranteed investors that the value of certain money market fund shares would remain at $1 per share. [3] Recent research estimates that an additional 21 to 31 funds would likely have also “broken the buck” in the absence of this government back-stop. [4]

Concerns regarding the consequences of sudden customer redemptions prompted the SEC to press on with money market fund reform. In 2010, the SEC introduced significant changes to the regulatory framework, including mandated daily and weekly liquidity levels, shorter portfolio maturities, and stress testing. A 2012 study by the SEC and the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) led to the proposal of further amendments in 2013 and the adoption of the final rules. [5]

New Rules

Table 1 presents an overview of the new SEC money market mutual fund rules. Most of the reforms target the holdings of liquid assets, where the term “liquidity” has a specific regulatory definition.

| Table 1: Overview of the 2014 Money Market Mutual Fund Rule Changes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Money Market Fund Reform | Final Rule | Implementation Date |

| Stress Testing | Funds must test their ability to maintain weekly liquid assets of at least 10% in response to several SEC-defined stress scenarios. Results must be presented to the fund’s board at regular intervals. | 14 April 2016 |

| Disclosure | Daily and weekly liquid assets as a percentage of total fund assets must be displayed on a website daily. Prior day net shareholder flows must also be displayed. | 14 April 2016 |

| Floating NAV | Non-exempt funds price and transact at a net asset value per share that “floats” based on the underlying fund holdings calculated to four decimal points. | 14 October 2016 |

| Liquidity Fee | If weekly liquid assets fall below 30%, the fund may impose a 2% redemption fee. If weekly liquid assets fall below 10%, redemptions are subject to a fee up to 2% unless the fund’s board votes otherwise. | 14 October 2016 |

| Redemption Gate | If weekly liquid assets fall below 30%, a fund’s board may suspend redemptions for up to 10 days. | 14 October 2016 |

Liquid assets are defined under the Investment Company Act of 1940 in Rule 2a-7, revised in 2010 and 2014. [6] This rule, which governs the operations of money market funds, defines two types of liquid assets, daily and weekly, corresponding to the ability to convert to cash within one or five business days, respectively.

Since 2010, when a fund’s daily liquid assets drop below 10% of total assets, the fund (other than municipal funds, which are exempt from this requirement) is prohibited from acquiring any new asset other than daily liquid assets. Similarly, if weekly liquid assets drop below 30% of total assets, the fund cannot acquire any new asset other than a weekly liquid asset. [7]

Stress Testing

Perhaps the most significant of the 2014 reforms is the enhanced stress testing requirement. This reflects the SEC’s concern that money market funds be prepared to deal with particular events such as interest rate changes, higher redemptions, and changes in credit quality of the portfolio. Since the draft rules in 2010, the SEC has required money market fund managers to examine a fund’s ability to maintain a stable net asset value per share in the event of such shocks.

However, starting in April 2016, money market funds will be required to conduct substantially different, enhanced stress testing. The new prescriptive stress testing regime is designed to minimize the possibility of a failure by forcing money market funds to regularly ask what would happen to their liquidity position under adverse market conditions.

In particular, the new regulations require funds to test their ability to maintain weekly liquid assets of at least 10% of total assets in response to several scenarios. The hypothetical stress events include:

- increases in the level of short-term interest rates;

- a downgrade or default of particular portfolio security positions; and

- a widening of spreads compared to the indexes to which portfolio securities are tied.

Additionally, these stress scenarios must include increases in shareholder redemptions to various levels, and management is encouraged to add any other combinations of events deemed relevant.

Recent litigation—the case of the SEC vs. Ambassador Capital Management in 2014 for example—has shown that portfolio managers and board members need to be keenly aware of, and fully understand the complex stress testing requirements described in rule 2a-7 of the Investment Company Act of 1940. Failure to implement even one dimension of the prescribed stress scenarios can result in severe penalties for the firm and its officers.

Stress Testing Example

We constructed a stylized balance sheet for a hypothetical money market fund, based on the N-Q filing of a major US money market mutual fund in Q4 of 2014. The filing gives detailed information on the portfolio holdings of the fund, including commercial paper, certificates of deposit (CDs), variable rate notes, fixed rate notes, and repurchase agreements (“repos”). An overview of the hypothetical money market fund holdings are shown in Table 2.

| Table 2: Hypothetical Money Market Fund Portfolio Holdings | |

|---|---|

| Security | Percentage of Total Assets |

| Commercial Paper | 49.2% |

| CDs | 21.6% |

| Variable Rate Notes | 5.4% |

| Fixed Rate Notes | 7.0% |

| Repurchase Agreements | 13.8% |

We assume that, prior to each of the stress scenarios, the fund holds 1% of its assets in cash and that 41% of total assets are weekly liquid assets. [8] We then subject the portfolio to three of the stress tests required under the new SEC regulations, and report the required measures: weekly liquid assets and principal volatility.

Stress Test Scenario 1 and 2: Interest Rate and Spread Risk

The first stress test scenario addresses an increase in the short-term interest rate. We subject the portfolio to a stress test scenario in which the 1-month and 3-month treasury rates increase simultaneously by 30 basis points (bps). [9] We assume this increase in rates continues to hold throughout the stress period of 10 business days. As required under the new rule, we consider various different assumptions about shareholder redemption rates. We assume they increase by 10%, 20%, or 30%, respectively, and remain at that level over the course of the 10-day stress period.

The second stress test scenario addresses a widening of spreads. In particular, the scenario assumes that credit spreads increase by 1.5%. [10] The results of both scenarios are shown in Table 3 below.

| Table 3. Stress Test Results for Floating NAV Fund: Interest Rate and Spread Shocks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in Interest Rates | Increase in Spreads | |||

| Redemption Increase | Weekly Liquid Assets | Principal Volatility | Weekly Liquid Assets | Principal Volatility |

| 10% | 34.7% | 0.7% | 34.6% | 0.9% |

| 20% | 34.5% | 0.8% | 34.4% | 1.0% |

| 30% | 34.4% | 0.8% | 34.2% | 1.0% |

The left side of the table, under the heading “increase in interest rates,” shows the stressed levels of weekly liquid assets after the 10-day shock has run its course. The liquidity level declines several percentage points to about 34.7% under the 10% increase in redemption rates and down to 34.4% under the more severe 30% increase.

This stress test reveals an important insight about this particular hypothetical money market fund: the interest rate shock and the spread shock scenarios have a profound effect on weekly liquid assets, even for a mild increase in redemption rates of 10%. Additionally, an increase in redemption rates that is three times higher, at 30%, does not change the results substantially. In other words, for this kind of money market portfolio, redemptions have less of an effect on existing shareholders than changes in interest rates. This illustrates the ways in which stress testing allows funds to glean valuable business insight into the dynamics of their portfolio.

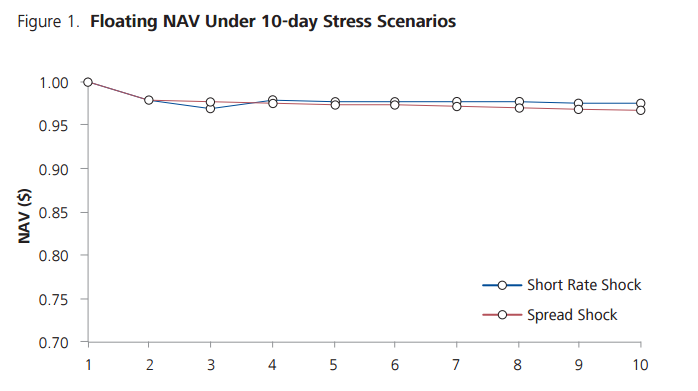

We also show the results in terms of principal volatility in the third and fifth columns of Table 3. Volatility is given by the typical statistical measure—the standard deviation—of NAV. The results indicate that the volatility of NAV would be about 0.8% in response to the interest rate shock and about 1% under the spread shock. Since there is little historical experience with floating NAV funds to put these numbers in context, it is useful to plot the NAV over the course of the 10-day stress event, shown below in Figure 1.

When the Reserve Primary Reserve Fund “broke the buck” in 2008, despite having a nominally non-floating NAV, it did so by 3%. In our interest rate shock scenario, the NAV does not drop as steeply, but it does experience a significant decline of nearly 2%. While this is a rather severe decrease, it should be kept in mind that the stress scenario envisioned here is an extreme, overnight move in short rates and in spreads.

Additionally, we note from the graph that the spread shock results in an even larger decrease in NAV. This is likely due to the fact that the spread shock is a 1.5% increase in spreads, occurring in one day, which would be a historically rare event. Of course, the appropriate parameters of the stress test would depend on many factors. A key part of the effort to design an informative stress test would be to use an appropriate stress-testing range for the relevant parameters.

Lastly, it is interesting to note that the decline in NAV occurs almost entirely in the first two days of the stress period, even though redemptions continue to occur at an elevated level for the entire 10 days. This again reflects the fact that, for typical money market portfolios, redemptions have much less of an effect on existing shareholders than the initial change in interest rates or spreads.

Stress Test Scenario 3: Downgrade Risk

The third shock, shown in Panel B, is a major counterparty downgrade. We assume that the counterparty comprises either 2% (shown on the left) of the commercial paper held in the portfolio (shown on the left), or 5% (shown on the right). For illustration purposes, we assume that the downgrade results in a 20% reduction in the value of the notes.

| Table 4. Stress Test Results for Floating NAV Fund: Counterparty Downgrade | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2% Fraction of CP | 5% Fraction of CP | |||

| Redemption Increase | Weekly Liquid Assets | Principal Volatility | Weekly Liquid Assets | Principal Volatility |

| 10% | 34.7% | 1.2% | 34.6% | 1.3% |

| 20% | 34.4% | 1.8% | 34.4% | 1.9% |

| 30% | 34.3% | 2.3% | 34.2% | 2.5% |

The results indicate that the reductions in weekly liquid assets are on par with the first two stress scenarios, but the increase in principal volatility is more varied and can be higher. For a high redemption-rate scenario, the variation in NAV can reach 2.5%. Again, assessing whether that is large or small requires an objective view as to what would also be reasonable variation during times of stress.

Conclusion

The SEC’s money market fund reforms will undoubtedly change the way that many money market funds operate in a substantive way. The reforms will create new challenges, including enhanced data management, new models for valuing positions and contingencies, and additional report generation and submission capabilities.

Risk management procedures will need to be augmented to include evaluation of fund liquidity under complex new stress scenarios in order to ensure compliance with the new rules. Economic and quantitative issues arising from this new framework will need to be dealt with promptly.

We expect that forthcoming rules on stress testing from the SEC for broker-dealers will present further challenges, and we will provide an update when those draft rules become available.

Seven Stress-Testing Issues to Consider

Based on our experience with stress testing methodologies, here is a list of seven questions money market fund boards should be asking when they assess the results presented to them.

- Do the scenarios cover all SEC-mandated stress testing scenarios?

- Is management making full use of the testing framework by including other relevant scenarios of business interest?

- Are the parameters chosen for the stress testing scenarios realistic?

- How often are the parameters of the approach recalibrated to reflect changes in the portfolio?

- How effective is the internal validation of the methodology used?

- What is the margin of error (confidence interval) of the results presented?

- What is the best way to summarize and present the results of a set of stress tests?

Endnotes:

[1] Money Market Fund Reform; Amendments to Form PF: Final Rule, Securities and Exchange Commission, 79 Fed. Reg at 47,736 (14 August 2014).

(go back)

[2] Tara Siegel Bernard, “Money Market Funds Enter a World of Risk,” The New York Times, 17 September 2008.

(go back)

[3] The US Treasury Department announced on 19 September 2008 that up to $50 billion of the Exchange Stabilization Fund would temporarily be made available to guarantee the $1 share price of participating money market funds. The program expired one year later. Ultimately, there were no claims paid out under the program.

(go back)

[4] S.A. Brady, K.E. Anadu, and N.R. Cooper, “The stability of prime money market mutual funds: sponsor support from 2007 to 2011,” Risk and Policy Analysis Unit Working Paper, RPA 12-3, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2012.

(go back)

[5] US Securities and Exchange Commission Division of Risk, Strategy, and Financial Innovation, “Response to Questions Posed by Commissioners Aguilar, Paredes, and Gallagher,” 2012; and the Financial Stability Oversight Council, “Proposed Recommendations Regarding Money Market Mutual Fund Reform” 2012.

(go back)

[6] The rule also determines what instruments are eligible investments for money market mutual funds.

(go back)

[7] Additionally, Rule 2a-7 prohibits funds from investing more than 5% of total assets in illiquid securities, where illiquid is defined as a security that cannot be sold or disposed of in the ordinary course of business within seven (calendar) days at approximately book value.

(go back)

[8] The average prime money market fund had weekly liquid assets of 41.3% as of December 2014. See US Securities and Exchange Commission Division of Investment Management, “Money Market Fund Statistics,” (2 June 2015).

(go back)

[9] At current rate levels, this represents a very substantial increase in short-term rates.

(go back)

[10] Again, this represents a substantial increase in credit-sensitive interest rates relative to current levels.

(go back)

Print

Print