Yvan Allaire is Emeritus professor of strategy at Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and Executive Chair of the Institute for Governance of Private and Public Organizations (IGOPP); François Dauphin is Director of Research of IGOPP and a lecturer at UQAM. This post is based on their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes: The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here); and Pre-Disclosure Accumulations by Activist Investors: Evidence and Policy by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Robert J. Jackson Jr., and Wei Jiang.

Pershing Square Capital Management, an activist hedge fund owned and managed by William Ackman, began hostile maneuvers against the board of CP Rail in September 2011 and ended its association with CP in August 2016, having netted a profit of $2.6 billion for his fund. This Canadian saga, in many ways, an archetype of what hedge fund activism is all about, illustrates the dynamics of these campaigns and the reasons why this particular intervention turned out to be a spectacular success… thus far.

The Canadian Pacific Railway Case

In 2009, the Chairman of the board of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) asserted that the company had put in place the best practices of corporate governance; that year, CP was awarded the Governance Gavel Award for Director Disclosure by the Canadian Coalition for Good Governance. Then, in 2011, CP ranked 4th out of some 250 Canadian companies in the Globe & Mail Corporate Governance Ranking. [1] Yet, this stellar corporate governance was no insurance policy against shareholder discontent.

Pershing Square began purchasing shares of CP on September 23, 2011. They filed a 13D form on October 28th showing a stock holding of 12.2%; by December 12, 2011, their holding had reached 14.2% of CP voting shares, thus making Pershing Square the largest shareholder of the company.

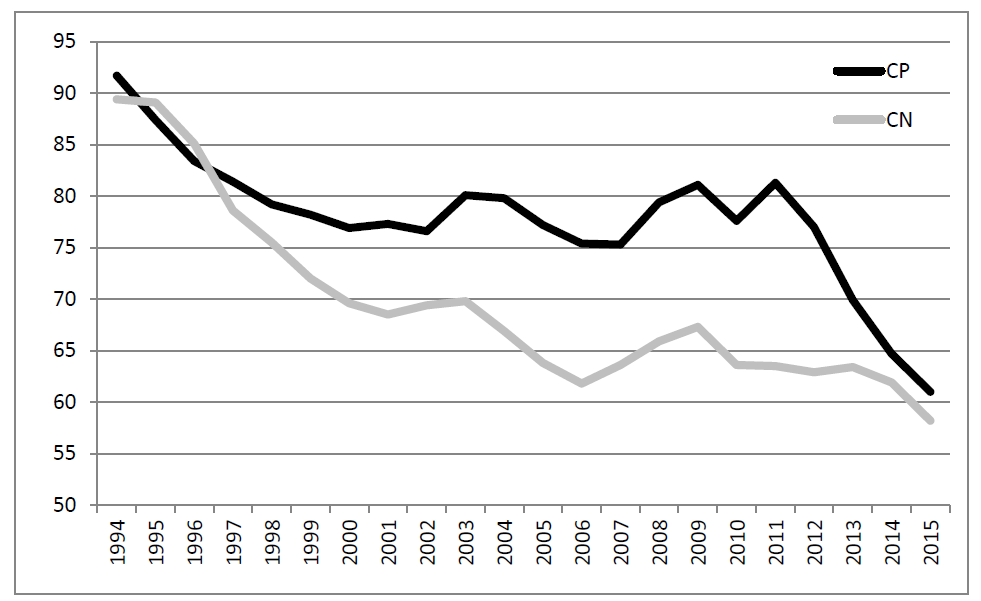

On February 6, 2012, Ackman, with Hunter S. Harrison (retired CEO of CN—direct competitor of CP and leader in efficiency among Class 1 North American railways—and his candidate for CEO of CP) by his side, made a fact-based presentation about the shortcomings and failings of the CP board and management. Harrison and Ackman stated that their goal for CP was to achieve an operating ratio of 65 for 2015 (down from 81.3 in 2011—the lower the ratio, the better the performance).

The Board qualified Harrison’s (and Ackman’s) targets of “shot in the dark”, showing a lack of research and a profound misunderstanding of CP’s reality. Relying on an independent consultant report (Oliver Wyman Group), Green mentioned that Harrison’s target for CP’s operating ratio was not achievable since CP’s network was characterized by steeper grades and greater curvature thus adding close to 6.7% to the operating ratio compared to its competitors. [2]

On April 4th 2012, Bill Ackman came out swinging in a scathing letter to CP shareholders disparaging CP’s Board of directors in general, and its CEO, Fred Green, in particular. According to Mr. Ackman, “under the direction of the Board and Mr. Green, CP’s total return to shareholders from the inception of Mr. Green’s CEO tenure to the day prior to Pershing Square’s investment was negative 18% while the other Class I North American railways delivered strong positive total returns to shareholders of 22% to 93%.” [3] Thus, according to him, “Fred Green’s and the Board’s poor decisions, ineffective leadership and inadequate stewardship have destroyed shareholder value.” [4]

A few hours before the annual meeting, CP issued a press release in which it stated that Fred Green had resigned as CEO, and that five other directors, including the Chairman of the Board, John Cleghorn, would not stand for re-election at the company’s shareholder meeting.

Pershing Square had won the proxy fight; all the nominees proposed by Ackman were elected.

Almost exactly five years after first buying shares of CP, Ackman confirmed in August 2016 that Pershing Square would sell its remaining shares of CP, thus formally exiting the “target.” Over those five years, CP has generated a compounded annualized total shareholder return of 45.39% (between September 23, 2011 and August 31, 2016), a performance well above the CN and the S&P/TSX 60 index (CP is a constituent of that index). Pershing Square pocketed an estimated $2.6 billion in profits for its venture into CP.

With massive reductions in the workforce, a transformation of the operations and a radical change of the CP’s organizational culture, CP is undoubtedly a different company from what it was before the proxy fight. In early September 2016, Bill Ackman resigned from CP’s Board, officially concluding this episode.

Lessons in corporate governance

In this day and age, the CP case teaches us that no matter its size or the nature of its business, a company is always at risk of being challenged by dissident shareholders, and most particularly by those funds which make a business of these sorts of operations, the activist hedge funds. Of course, a number of critical features of this saga can be singled out to explain the particular success of this intervention, but this is not the focal point of this post. [5] After all, a widely held company with weak financial results and a stagnating stock price will inevitably attract the attention of these funds.

But the puzzling question and it is an unresolved dilemma of corporate governance remains: how come the board did not know earlier what became apparent very quickly after the Ackman/Harrison takeover? Why would the board not call on independent experts to assess management’s claim that structural differences made it impossible for CP to achieve a performance similar to that of other railroads? The gap in operating ratio between CP and CN had not always been as wide. In fact, as shown in Figure 1, CP had a lower operating ratio than CN during a period of time in the 1990s (Of course, CN was a Crown corporation at that time). The gap eventually widened, reaching unprecedented levels during Fred Green’s tenure (the last full year of operating ratios attributable to Green was in 2011).

Figure 1. Evolution of the operating ratio (%—left scale) for the CP and CN (1994-2015)

How could the board have known that performances far superior to those targeted by the CEO could be swiftly achieved?

Lurking behind these questions is the fundamental flaw of corporate governance: the asymmetry of information, of knowledge and time invested between the governors and the governed, between the board of directors and management. In CP’s case, the directors, as per the norms of “good” fiduciary governance, relied on the information provided by management, believed the plans submitted by management to be adequate and challenging, and based the executives’ lavish compensation on the achievement of these plans. The Chairman, on behalf of the Board, did “extend our appreciation to Fred Green and his management team for aggressively and successfully implementing our Multi-Year plan and creating superior value for our shareholders and customers.” [6] That form of governance is being challenged by activist investors of all stripes.

Their claim, a demonstrable one in the case of CP, is that with the massive amount of information now accessible about a publicly listed company and its competitors, it is possible for dedicated shareholders to spot poor strategies and call for drastic changes. If push comes to shove, these funds will make their case directly to other shareholders via a proxy contest for board membership.

Corporate boards of the future will have to act as “activists” in their quest for information and their ability to question strategies and performances.

The full paper is available for download here.

Endnotes

1The Board Games, The Globe & Mail’s annual review of corporate governance practices in Canada.(go back)

2Deveau, S. “CP Chief Fred Green Defends his Track Record.” Financial Post, March 27, 2012.(go back)

3Letter addressed by William Ackman to Canadian Pacific Railway shareholders, Proxy Circular from April 4th, 2012.(go back)

4Ibid.(go back)

5The case analysis identified four factors that are rarely present in other cases of activism, a fact which explains why few of these interventions achieve the level of success of the CP case.(go back)

6Cleghorn, John. Chairman’s letter to shareholders, CP’s Annual Information Form 2011.(go back)

Print

Print