Hywel Ball is Managing Partner for Assurance, UK and Ireland; Loree Gourley is Director of Regulatory and Public Policy; and Brandon Perlberg is Associate Director of Regulatory and Public Policy, all at EY UK. This post is based on an EY UK memorandum by Mr. Ball, Ms. Gourley, Mr. Perlberg, Christabel Cowling, and Peter Flynn. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Agency Problems of Institutional Investors by Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Scott Hirst (discussed on the Forum here), and Index Funds and the Future of Corporate Governance: Theory, Evidence, and Policy by Lucian Bebchuk and Scott Hirst (discussed on the forum here).

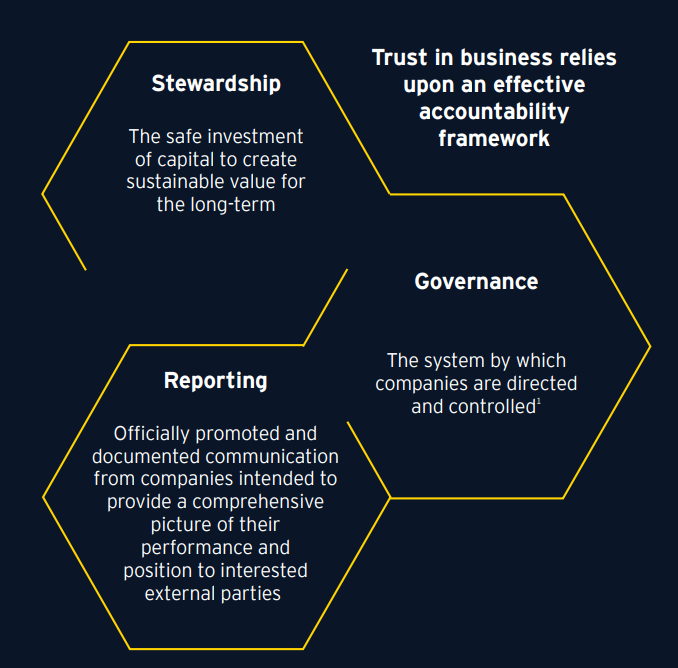

Vital to rebuilding trust in business is an effective accountability framework based on good stewardship, governance and reporting. Within this, transparency over stewardship of investments plays a fundamental role in providing confidence to a broad range of stakeholders. Pursuing greater transparency drives greater accountability, and promotes a critical shift from short-term thinking to creating long-term value.

What is this review about?

This is first-of-its kind research designed to enable a better understanding of how UK-based asset managers and asset owners are currently reporting on and engaging with their investee companies on stewardship. We analysed recent stewardship reporting by the 30 largest UK investors who are signatories to the UK Stewardship Code (20 asset managers and 10 asset owners). We then assigned scores based on the depth of their reported stewardship activity across different areas of investor priority. The findings provide a comprehensive picture of investor priorities and expectations, and offer unique insights about the journey toward more transparent reporting that promotes the safe investment of capital for the long-term.

More deeply understanding investor priorities helps inform* our statutory audit and reporting work. This, in turn, better enables us to meet the needs of investors as the ultimate beneficiaries of our product, as well as those of wider society, in the spirit of increasing trust in business.

Why is it important?

Regulation is an important driver of better stewardship and the UK Stewardship Code has long been recognised as a leader in this area. In 2010, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) published the first UK Stewardship Code, which ultimately led to the creation of similar sets of principles in as many as 20 countries. In its current revised form, the Code establishes higher expectations of investors, putting greater pressure on asset managers and owners to report and engage more effectively.

Stewardship, along with governance and reporting, is a critical component to enhance corporate accountability, and through this the attractiveness of the UK as a place to do business. Greater transparency over investor expectations, how investors engage with investee companies and their areas of greatest priority helps to drive stronger governance and more effective corporate reporting.

Yet, even with these regulatory interventions and revised codes, more needs to be done to facilitate a deeper dialogue between business, investors and society to strengthen accountability in line with changing expectations.

Market-wide engagement

Establishing and enacting best practice requires collaboration across the market. Therefore, in addition to reviewing the reporting of the 30 largest UK investors, we also conducted one-on-one meetings and engaged with several industry leaders, subject matter experts and academics to develop our methodology and glean insights that helped shape our thinking. This research revealed eight investor priority areas and highlighted multiple opportunities to enhance stewardship reporting across them.

Summary insights and findings

Our findings

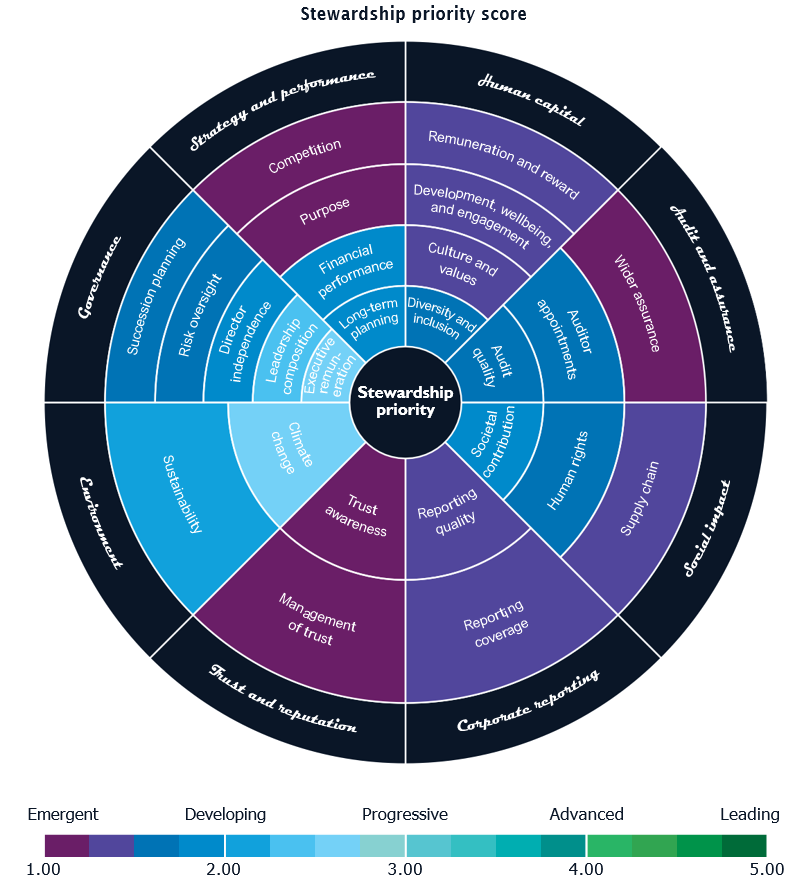

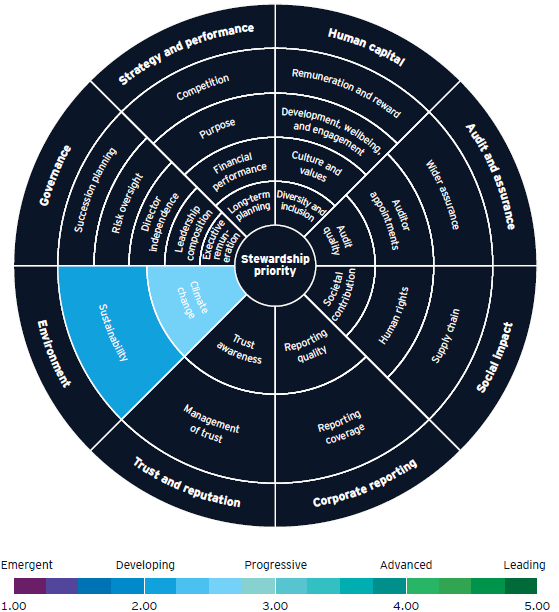

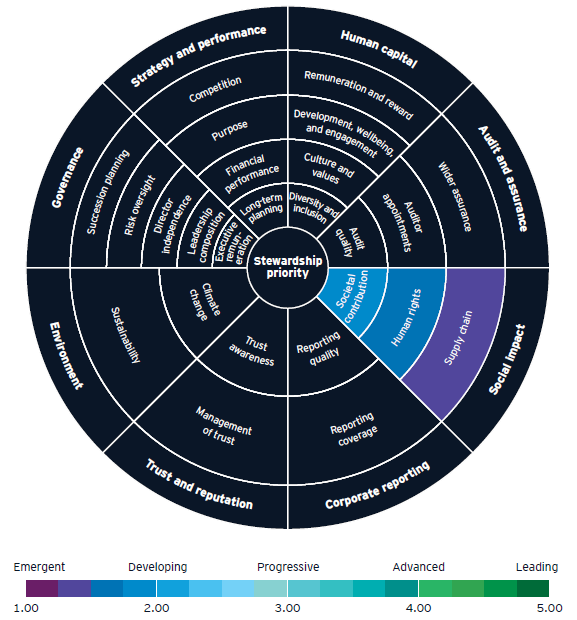

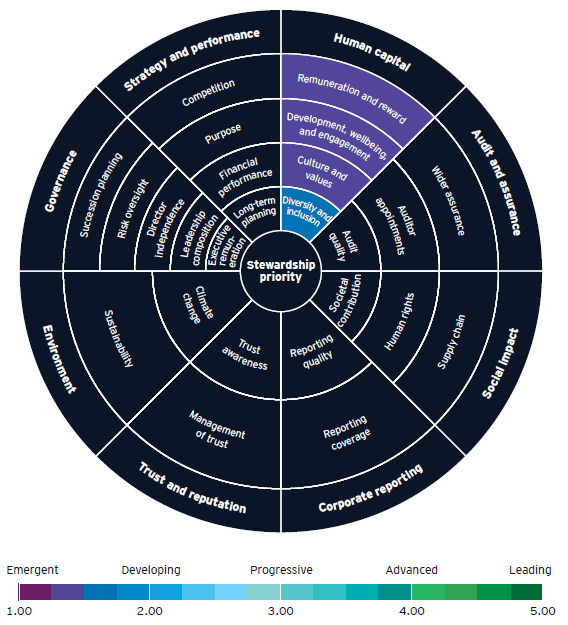

As shown in the wheel below, we divided stewardship into eight segments and rated current practices based on material published by the 30 largest UK investors.

Our review provides a view on investor stewardship priorities in the aggregate, and contrasts findings between asset managers and asset owners.

Highlights

Environment and Corporate Governance lead the way.

These two areas of investor focus were the only ones to score above two out of five against our stewardship priority scale, signalling the relatively greater priority placed upon them by investors.

Corporate Reporting, Audit and Assurance, and Trust and Reputation require the most attention.

These areas scored the lowest, but also present some of the clearest opportunities for investors to enhance their stewardship activities.

Stewardship reporting is still evolving.

We found a broad range of reporting styles and approaches, reflecting that stewardship reporting is in the relatively early stages of its evolution and has some way to go.

Asset owners scored significantly lower than asset managers across all categories and sub-categories.

This result is unsurprising given that the existing UK Stewardship Code does not ascribe responsibilities uniquely to asset owners as distinct from other classes of institutional investors, and given that asset managers’ reporting on their stewardship activity is a key element in demonstrating value to their clients. In view of the increasing pressures asset owners are facing, we expect asset owners’ scores to improve in the future.

Sources of increasing pressures on asset owners include:

- The revised UK Stewardship Code, which is likely to place more rigorous and specific stewardship reporting requirements on asset owners.

- The government’s green finance strategy, which sets out its expectations for all listed companies and large asset owners to report on climate-related disclosures in line with the Financial Stability Board’s task force.

- The Pensions Regulator’s updated Defined Contribution Investment Guidance, which introduces new requirements relating to the stewardship of investments (including exercising rights and engagement activities) and the extent that members’ views (including ethical, social and environmental) are considered when planning investments.

In-depth review: the top five investor priority areas

We take a detailed look at current practice on the top five investor priority areas, based on our review. We set out our observations and suggestions for ways forward.

Environment

The priority that investors are calling the ‘defining issue of our time’.

Summary

Environmental impact represents the greatest stewardship priority for UK investors today. However, greater transparency on investor polices and engagement outcomes is needed to help signal expectations and more rapidly evolve the operating models of exposed business sectors.

Current reporting—our findings

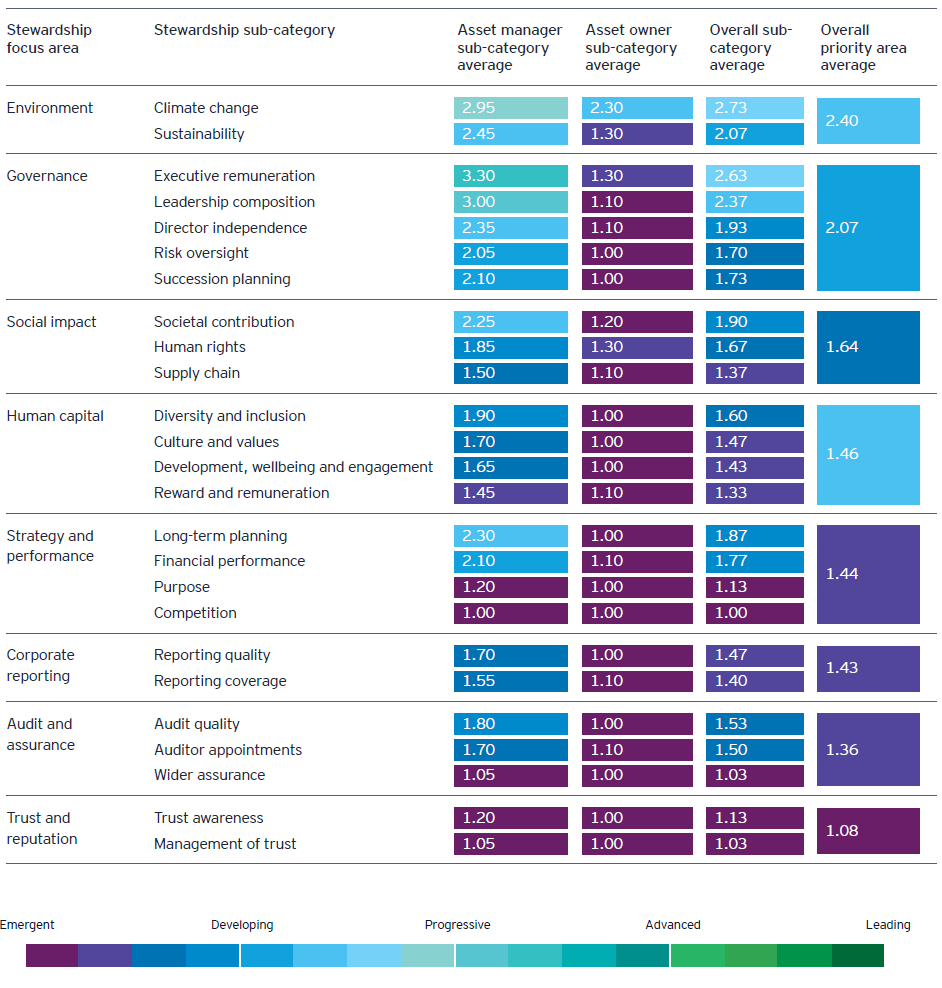

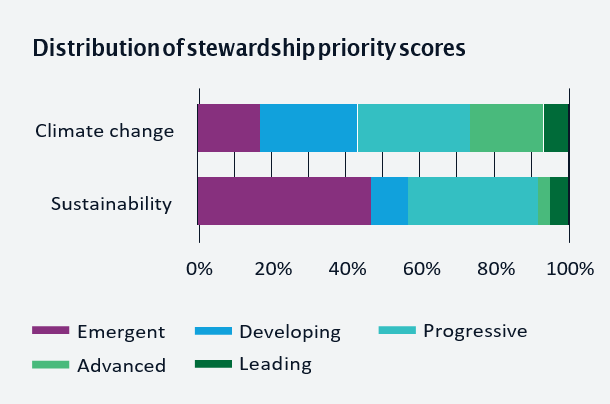

We examined recent stewardship reporting on environmental issues around climate change and sustainability. Our analysis reflected an average rating of 2.40—a stewardship priority score sitting between developing and progressive—which signals investor engagement, sometimes with clearly communicated policies to match. Within this, climate change specifically scored even higher at 2.73, evidencing its status as a major investor priority, scoring higher than any other priority.

Notably, our review also found that climate change commands a vastly greater stewardship focus from asset owners (a score of 2.30) than any of the other 24 stewardship sub-categories we reviewed. This finding is particularly significant in view of the influence that asset owners wield within the investment chain. This suggests that the focus on climate change from asset owners has helped drive engagement in the area from asset managers.

Asset managers told us that they focused on the environment in large part because of the risk of business disruption. This includes market risks associated with climate change (such as shifting demand patterns for electric cars and fuels). Investors also told us they recognise that some sectors and geographies are more exposed to climate-related risks than others, and that this informs investors’ assessment of risk materiality and how they engage.

Our review identified multiple references to broader sustainability matters within stewardship reports, including investor engagement on water use, resource scarcity and plastics use. Certain sectors are more likely than others to be engaged on these matters, such as the use of plastics by chemicals and consumer products companies. However, with an average rating of 2.07—a priority score of developing—the broader sustainability agenda appears to receive significantly less attention from investors than climate change.

Investor engagement—current practices

Investors’ current focus is on understanding how companies are actively assessing and managing their climate risks. Our review indicates that investor engagement with boards and senior management frequently covers topics including, but not limited to:

- Addressing companies’ carbon emissions

- Adapting to climate change

- Adapting to resource scarcity

- Preparing for physical climate risks

- Developing mitigation plans

- Market risks stemming from shifting demand patterns

- Quantifying climate change exposure as a financial risk

Investors apply a heightened degree of scrutiny for sectors that have a higher exposure to climate change. One investor shared with us their expectation that exposed companies demonstrate how their business model has been adapted to enable success within its future operating context. Among the questions that investors told us that such companies should be asking themselves are: how are they preparing for a low carbon economy; how are they aligning with the Paris Agreement; and how are they ensuring their business is resilient in a changing climate.

Another investor shared an example of how their engagement with a major energy company contributed to that company’s adoption of carbon emission targets, linking these to pay and modifying lobbying behaviours. Recent news items confirm investor engagement along similar lines.

We also observed multiple investors applying ESG tools that help them to take environmental considerations into account when making investment decisions. Such tools use multiple ESG data sources and proprietary analysis to feed into portfolio managers’ and analysts’ overall data sets, integrating ESG into the normal investment process and demonstrating its central role in investor decision-making.

There has been considerable focus on the corporate reporting of environmental factors. Investors now expect meaningful disclosures demonstrating the impact of climate matters on individual companies. One investor told us that companies failing to provide sufficient evidence may be at risk of divestment. This finding is consistent with a recent EY survey, which also found climate change to be among the most important factors in investment decision-making. The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures—2019 Status Report found that while progress has been made in recent years, the level of disclosure of climate-related financial information remains insufficient for investors and that greater clarity is required as to the potential financial impact on companies of climate-related issues.

Some pension funds are also actively engaging in the area of climate risks, with at least one linking the real value of its members’ retirement income to the state of the environment in which they will be retiring.

As noted earlier, our analysis reflects significantly more transparent stewardship reporting from asset owners on climate change than any of the other 24 stewardship sub-categories we assessed.

Shifting the dial—opportunities for best practice

Addressing threats to the natural environment is a shared responsibility, so coordinated collective action is vital. Changes to law and regulations can establish the systems and rules that align company behaviour with achieving climate goals across national and global economies. Investors therefore have an interest in continuing to engage in the policy-making process and urging their investee companies to subscribe to targets and initiatives that emerge in the policy space.

There is also a clear opportunity for investors to report more about the outcomes of their environment-related engagement with companies. Our analysis, which gives scores of advanced and leading where stewardship reporting details companies’ policy, engagement and outcomes, showed that less than 10% of our review population are doing this with regard to the broader sustainability agenda. We recognise that outcomes can be difficult to report because they can be macro (sector-wide) or micro (company-specific), and because they often result from numerous factors and points of influence beyond a single engagement. However, we consider that the potential benefits of expanded reporting in this area would be significant, given the broad range of stakeholders affected and the positive impact that news of effective stewardship outcomes could have on trust in business.

Putting it into practice. Questions for investors to ask and boards to answer

- How does the company assess its exposure to climate-related risks? How does it quantify its exposure as a financial risk?

- What steps has the company taken to mitigate against business disruption from climate-related risks and shifting demand patterns? How has the company’s business model prepared for the transition to a low-carbon economy?

- How does the company assess the adequacy of its climate-related disclosures? How does it determine the stakeholders to whom they are directed?

- How is the company helping to tackle climate change?

- How confident is the company in the accuracy and robustness of its environmental and/or climate change disclosures?

Climate change commands a vastly greater stewardship focus from asset owners than any of the other 24 stewardship sub-categories we reviewed.

Corporate Governance

A lens through which investors focus on multiple stewardship priorities.

Summary

Corporate governance is high on investors’ stewardship agenda. However, there are still opportunities for investors to better signal their expectations to investee companies, together with explanations of the consequences if these expectations are not met. The 2018 UK Corporate Governance Code introduced new requirements for companies to report on their consideration of stakeholder interests and identify emerging risks, both of which present opportunities for deeper investor engagement.

Current reporting—our findings

In assessing investor engagement on corporate governance, we reviewed stewardship reporting relating to executive remuneration, director independence, leadership composition, risk oversight and succession planning.8 Aggregated, corporate governance obtained an average rating of 2.07—a stewardship priority score of developing—which ranked second among the eight stewardship focus areas we reviewed. There was a significant variance between the average rating for asset owners (1.10) and that for asset managers (2.56), suggesting asset owners can wield greater influence in how asset managers engage with investee companies on governance-related topics.

Among the five sub-categories of governance we examined, executive remuneration (a score of 2.63) and leadership composition (a score of 2.37) received the highest stewardship priority scores, indicating investor engagement, often accompanied by clearly communicated polices. Director independence, succession planning and risk oversight followed, with respective average scores of 1.93, 1.73 and 1.70.

Our analysis uncovered multiple examples of investor engagement with remuneration committees to test for alignment between executive pay and the achievement of long-term value creation. The resulting comparatively high score for executive remuneration is therefore unsurprising, particularly given that CEO pay has risen substantially faster than average worker pay over the past decade.9 Politicians, journalists and other stakeholders have helped elevate this as a matter of public interest, contributing to its high placement within the stewardship agenda. Investor engagement in this area is likely to increase, as pay ratio regulations come into effect in 2020, requiring the disclosure of the ratio of the CEO’s pay to that of the company’s UK workforce.

We identified several examples of investors engaging on gender diversity with respect to board composition. Less common was engagement on a broader range of diversity dimensions, including ethnicity, age, professional background, industry sector experience and geographic location.

Several investors did stress that diverse boards make better decisions. Many stated that where a board fails to make sufficient progress with its diversity, its nomination and/or governance committees would be held accountable for a lack of commitment to board effectiveness.

Investor engagement—current practices

As part of our review, we assessed dozens of investor case studies relating to corporate governance and interviewed several asset managers on how they engage on corporate governance. While we noted some disagreement among investors as to what represents ‘good corporate governance’, we identified several areas as being of notable interest

to them. These include, but are not limited, to:

- Diversity of thought, gender, ethnicity, skills, tenure and experience

- Director independence and its impact on board decision-making

- The start of succession planning (i.e., well before any impending boardroom departures) and the breadth of candidates considered (e.g., including searches looking beyond candidates with previous CEO experience)

- The assessment of board members’ capacity (i.e., over-boarding) and the potential impact on board effectiveness

- The relationship between remuneration policies, company strategy and long-term value generation

- The approach for identifying, assessing (qualitatively and quantitatively) and managing risk (both principal and emerging)

- Incidents of fraud, bribery and corruption, and related investigations

- The manner in which stakeholder interests are integrated into company strategy

Related to the areas above, several investors whose stewardship reports we reviewed mentioned having in-house teams who are dedicated to assessing companies’ corporate governance strength. While nearly all referenced their discussions with board members and requests to boards

for information, many also revealed that their corporate governance assessments also leveraged data available through external resources, such as BoardEx. We observed at least one investor adopting a sophisticated framework for assessing corporate governance strength based on potential indicators of good corporate governance. Given the pressures (societal and political) placed on maintaining robust governance procedures, we expect that investors’ demands for governance-related information will continue to increase in the coming years.

Shifting the dial—opportunities for best practice

We identified a number of potential opportunities for enhancing engagement on corporate governance:

Board effectiveness: several investors characterised their engagement with boards as enabling an assessment of board effectiveness. However, only one investor provided details as to its framework, data points reviewed and policies for assessing this. Greater transparency from investors may prompt more useful disclosures from companies and enable cross-company comparisons.

Stakeholders: to varying degrees, investors stewardship reporting reflected engagement around outcomes for stakeholders including employees, customers, communities and the environment. Greater corporate disclosure around how companies have considered stakeholder interests will be needed to comply with new legal requirements that directors disclose how they have discharged their duties under section 172 of the Companies Act 2006. This presents a clear opportunity for investors to signal how they integrate this data into their investment decision-making.

Leadership diversity: while numerous investors evidenced policies and engagement around gender diversity of boards, few demonstrated engagement around other dimensions of diversity, including ethnicity, skills and tenure. Still fewer provided evidence of any engagement on diversity at the senior management level. There is an opportunity to significantly broaden the diversity dialogue to promote greater overall diversity of thought at leadership levels. Leadership diversity: while numerous investors evidenced policies and engagement around gender diversity of boards, few demonstrated engagement around other dimensions

Risk oversight: Risk oversight was the least prioritised area of corporate governance on an investor-by-investor basis. New requirements under the 2018 UK Corporate Governance Code, which oblige companies to explain how they assess, identify and manage emerging risks, present an opportunity for more focused engagement from investors in this area.

Putting it into practice. Questions for investors to ask and boards to answer

- What steps are being taken by the nomination committee to achieve a truly diverse board, including diversity of thought, gender, ethnicity, skills, tenure and experience? How is diversity being pursued across the company’s senior management? How does it objectively assess the effectiveness of its overall leadership (board and executive) composition?

- How does the company’s executive remuneration policy help promote the appropriate balance between the pursuit of short-term targets and the achievement of long-term value generation?

- How do the board, executive leadership and senior management consider outcomes for employees, suppliers, customers, communities, the environment and other stakeholders in their decision-making?

- What is the company’s approach to identifying emerging risks? What emerging risks have been identified? What is the impact on the company’s strategy and business model? How does the board ensure it has sufficient oversight over the emerging risks?

Social Impact

Its critical link with long-term value is making this area increasingly important to investors.

Summary

Many investors see social impact as being linked to a company’s ability to both preserve and generate long-term value, with some offering evidence of holding boards to account on their companies’ social impact footprints. As an emerging area of importance, investors are likely to provide increasing transparency over their social impact policies and engagement activities, including how it is integrated into investment decisions.

Current reporting—our findings

Many of today’s institutional investors engage on what they perceive to be a clear link between the social impact of business activity and the achievement of long-term strategic business objectives. Our review identified three relatively common sub-categories of what we have termed ‘social impact’ stewardship: human rights, supply chain and societal contribution, with societal contribution being defined as an activity that produces a positive impact on the public.

For each of these three, our analysis reviewed evidence of investor focus on circumstances and dynamics external to investee companies.

Examples of this include, but are not limited to:

- Labour law violations by suppliers

- The prevalence of unethical business conduct in particular jurisdictions

- Negative outcomes for local communities (such as displacement of homes or agriculture)

We also considered investors’ policies with respect to goods that are widely viewed as having an adverse social impact, such as unconventional weapons and tobacco products. Although human rights issues frequently arise within a supply chain context, we analysed evidence of human rights engagement separately from supply chain, given the scope and scale of consequences that can result from business activity associated with human rights’ violations.

Among the three sub-components for social impact we observed that investor focus, as reflected in stewardship reporting, is strongest around societal contribution, which received a priority score of 1.90, compared with 1.67 for human rights and 1.37 for supply chain. Given the placement of individual savers along the investment chain, their interests in the aggregate present an opportunity to help influence the investment priorities of asset owners, and through them asset managers.

Investor engagement—current practices

Many investors that we spoke to emphasised that social impact is considered on a case-by-case basis, noting that it can vary widely depending on sector and geopolitical context. Our analysis found that where investors focus on the social impact of investee companies, it is frequently reflected in questions to boards and senior management on matters affecting local communities, such as displacement, and the quality of people’s lives, such as impact on local communities’ livelihoods. Investors also related their interest in the social value of the products and services of their investee companies, including in the areas of health, mobility, employment and education. We identified multiple instances where companies’ perceived failures to adequately engage with their wider stakeholders were linked by investors to adverse incidents affecting those stakeholders. This led to heightened scrutiny from investors. Conversely, we reviewed stewardship case studies which highlighted investor views that comprehensive stakeholder engagement can lead to better understandings around stakeholder needs, and that this in turn helps underpin value creation over the long term.

Importantly, investors told us that they treat social impact issues as core business matters when engaging on them with companies, informing the scope and importance of the questions typically asked. One investor provided us with an example of their engagement with an African mining company, where the social impact issues that arose led to questions on the external circumstances

that contributed to employee deaths, the related board-level conversations, the company’s plans to update its remuneration schemes, its relationship with local government and how it conversed with its regulators.

As part of our review, we also found that investor engagement on social impact matters have included requests for materials including, but not limited to:

- Sustainability strategy and action plans

- Transparent disclosures around labour management

- Audits performed on suppliers

- Human rights assessments

- Action plans and strategies to engage with local communities

Shifting the dial—best practice

We consider that there may be an opportunity for investors to expand the range of matters on which they engage with companies within a social impact context.

Our analysis also found that less than half (47%) of investors reported on their human rights engagements in a manner deemed developing or greater, and that only 30% reported on supply chain stewardship activity in a similarly prioritised fashion. This represents a clear opportunity to enhance stewardship reporting and potentially engagement as well.

According to the Global Slavery Index, 40.3 million people were victims of modern slavery in 2016, and $354 billion worth of products imported by G20 countries are deemed at-risk products of modern slavery. Greater transparency from investors on their stewardship policies and activities in these areas offers the potential not just to better communicate expectations and reduce these figures, but also to instil public confidence in operational business practices that are carried out responsibly and ethically.

Companies’ perceived failures to adequately engage with their wider stakeholders were linked by investors to adverse incidents affecting those stakeholders.

Putting it into practice. Questions for investors to ask and boards to answer

- How is the board assessing, managing and measuring the social impact of its business? What risks does it present to long-term value preservation and creation?

- What steps are being taken by the company to proactively engage with local communities and wider stakeholders?

Human Capital

Most investors agree on the importance of human capital, but few demonstrate deep engagement.

Summary

Despite a strong focus on human capital from companies, regulators and the wider public, investor engagement in this area appears to be generally immature. A more structured approach to human capital engagement would help enable greater consideration of stakeholder outcomes, align with societal expectations and support the preservation and creation of long-term value.

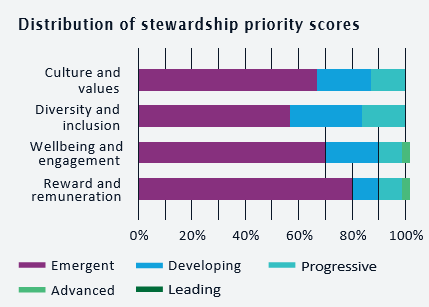

Current reporting—our findings

We examined recent stewardship reporting around four sub-categories of human capital: diversity and inclusion; culture and values; development, wellbeing and engagement; and reward and remuneration. We observed that the greatest focus is currently on diversity and inclusion, which received a stewardship priority score of 1.60, and on organisational culture and values, which was scored at 1.47. Notably, just one of the asset owners within our population of interest scored above 1.00 (emergent) in any of the four human capital subcategories we reviewed.

Compelling evidence exists correlating diversity with financial performance. Conversely, problems relating to organisations’ people and culture are regularly cited as contributory factors to business failures. The public sector Equality Duty now requires public bodies “to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations between different people when carrying out their activities”, resulting in diversity and inclusion requirements for business applying for government contracts. Asset managers’ focus on human capital is also influenced by the evolving legal and regulatory landscape relating to workforce disclosures, including gender pay gap reporting and proposed reporting on ethnicity pay gaps.

Investor engagement—current practices

We observed multiple investors that carve out a unique board responsibility for oversight of organisational cultures. Investors leading in human capital stewardship indicate that their engagement with companies may include requests and information relating to the following:

- Action plans for responding to gender and ethnicity pay gaps

- Diversity and inclusion statistics for different organisational cohorts

- Progression and pay data

- Detailed descriptions of the organisation’s current and desired cultures, including data points used to monitor culture

- Engagement to promote flexible working

- Extent of unconscious bias training

- Actions taken to promote paternity leave

- Recruitment plans

- Turnover and absenteeism rates

- Employee engagement scores

- Public disclosure of Word Development Indicators survey results

- Satisfaction of ISO 30414 standard for human capital reporting

Shifting the dial—best practice

Stewardship reporting often references matters such as organisational culture and workforce diversity and

inclusion, however for the majority of investors it reflects a significantly less robust level of investor challenge and probing for evidence and explanation than we observed for areas such as corporate governance and the environment.

This presents a clear opportunity for enhanced engagement. Under the UK Corporate Governance Code, boards of premium-listed companies are now required to report on their cultural monitoring and remediation activity. In support of that requirement, the FRC published Guidance on Board Effectiveness, which sets out detailed suggestions for cultural monitoring that may be of use to companies and investors alike. We note the distinction between employee engagement and organisational culture, and that companies relying solely on engagement survey results as their cultural data points may have significant cultural blind spots.

We also note the new requirement under the UK Corporate Governance Code that annual reports ‘should include an explanation of the company’s approach to investing in and rewarding its workforce’. Our analysis reflects investor stewardship generally being less prioritised in the related human capital areas of development, wellbeing and engagement and reward and remuneration. The former received an average stewardship priority score of 1.43, with only 30% of the investors we reviewed evidencing engagement beyond an emergent level. The latter received an average stewardship priority score of 1.33, with just 20% of investors engaging in more than an emergent manner.

The new reporting obligations, and work presently being pursued under the Workforce Disclosure Initiative, is liable to contribute to a change in these figures in the coming years. We also note recent statistics demonstrating widening income inequality in the UK, presenting an opportunity for investors to engage in social impact stewardship by more transparently demonstrating engagement around employee reward and remuneration.

None of the asset owners scored above 1.00 in any of the four human capital subcategories we reviewed.

Putting it into practice. Questions for investors to ask and boards to answer

- How does the company assess the level of alignment between its cultures, purpose, strategy and stated values? How does it ensure its findings are objective? How does it manage the gaps identified?

- How does the company support the hiring and progression of employees from underrepresented groups?

Strategy and Performance

There is a pressing need to align long-term investor focus with companies’ shorter-term incentives and objectives.

Summary

Investors apply a long-term lens when engaging on strategy and performance, but often identify shortfalls in how companies explain their long-term thinking, and the balance those companies strike between short-term incentives and achieving long-term objectives. Greater transparency is required on how investors press companies to deliver on their stated purposes, and in doing so build trust and create social value with all stakeholders.

Our findings—current reporting

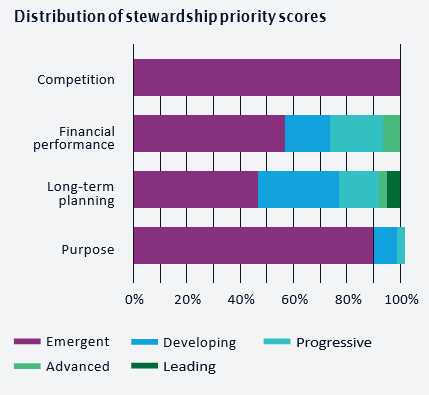

We assessed four sub-categories of strategy and performance: competition; financial performance; long-term planning; and purpose. Among these four, long-term planning and financial performance received the highest stewardship priority scores, rated 1.87 and 1.77, respectively. Among asset managers alone, long-term planning received a score of 2.30, reflecting the average reporting between the developing and progressive levels.

These findings suggest that while investors are clearly interested in companies’ financial performance—typically a short-term metric—they engage more around companies’ long-term thinking. In many ways, this reflects an alignment of incentives, with long-term investors wanting companies to plan similarly.

It also reflects present-day observations that some companies’ balance sheets reflect as little as 20% of the companies’ market value. The remainder is frequently represented by intangible unrecorded assets, such as a company’s ability to innovate and harness the assets are key to their future prospects, but at present are rarely represented as measures of performance. This was one of the catalysts for the founding of the Embankment Project for Inclusive Capitalism (EPIC), a coalition of 31 global organisations—including nine asset owners and nine asset managers with a combined $31 trillion in assets under management—which collectively developed an open-source framework for measuring and reporting on long-term value.

Investor engagement—current practices

The paramount importance of long-term business strategy and planning was universally emphasised by each of the investors with whom we spoke. Despite the emphasis they place on it, multiple investors told us that companies are not always adequately prepared to discuss their long-term thinking. One investor illustrated this by referring to roadshow meetings during which management teams present slide decks that highlight progress against quarterly targets

Another investor underscored this point by describing the significant level of research investors undertake prior to meeting with companies on the potential impact of megatrends such as climate change and rising inequality.but are often silent regarding the megatrends that could disrupt their business and industry over the coming decade.

Yet another investor we spoke to indicated they set five-year thematic engagement strategies on long-term topics such as energy transition to help structure the agenda for their meetings with company leadership.

Investors also repeatedly shared with us their interest in understanding how companies strike a balance between short-term incentives and achieving long-term objectives. One investor discussed their push for a longer-term orientation of stock awards at an investee company.

Shifting the dial—best practice

Among the four sub-categories of strategy and performance examined, competition, which received a stewardship priority score of 1.00, clearly presented the greatest opportunity for enhanced stewardship reporting. However, we do not believe that this necessarily represents the most important area in which to focus greater stewardship attention.

We do, however, consider there is a real opportunity for deeper engagement and transparency around how companies deliver on their purpose. Despite the subject receiving much attention over the past few years, purpose received a stewardship priority score of just 1.13, placing it among the bottom 20% of 25 sub-categories reviewed. Greater focus in this area would align with the likely increased regulatory interest in purpose as set out in UK Corporate Governance Code. It also has the potential not only to help enable sustainable performance and long-term value generation, but also to support boards in the shift from shareholder to stakeholder capitalism.

Putting it into practice. Questions for investors to ask and boards to answer

- What developments present the greatest potential to disrupt the company’s business over the next 5-10 years? How is the company planning for these?

- How does the company balance short-term incentives with long-term objectives?

- How does the company’s purpose inform its strategy?

- What are the most important non-financial drivers of value within the business and how does it monitor performance of these?

While investors are clearly interested in companies’ financial performance, they engage deeply around companies’ long-term thinking.

Time to take action

Do investors need better questions, or do companies need better answers?

Conclusions

Our analysis clearly shows that trust in business relies upon an effective accountability framework based on proactive investor stewardship, strong corporate governance and relevant and reliable corporate reporting. To improve their reporting practices and meet regulatory requirements, asset managers and assets owners will need to achieve greater transparency and clarity across all areas of stewardship, demonstrate publicly how they engage with investee companies and better communicate the outcome of that engagement. In turn, investee companies will need to prepare themselves for greater levels of engagement, primarily through better communications with all their stakeholder groups.

3 tools for change

Better questions

Our ‘putting it into practice’ set of questions are designed to enable richer stewardship for the benefit of all parties in the investment chain. We encourage institutional investors and investee companies alike to leverage these questions to enhance dialogues for the future.

Case studies that count

Our analysis of published material showed that, although case studies often provide good visibility on specific instances of engagement with investee companies, it was not always clear if they were representative of the investor’s stewardship activities as a whole. We therefore encourage institutional investors to more clearly demonstrate that the case studies and matters referenced within their stewardship reports reflect their overall engagement activity.

Benchmarking for the future

We intend to repeat our analysis and share latest developments. This will provide the opportunity to measure changes in investor priorities and identify emerging trends.

The journey ahead—are you ready?

Long-term value—counting what really counts

Long-term value lies at the centre of many of the issues discussed in this report, perhaps because it can be seen as the ultimate aim of effective stewardship. Yet, it has also traditionally been the source of tension across the investment chain based on the breadth of stakeholder requirements and inconsistencies in reporting frameworks and metrics.

There was a striking consensus amongst the diverse group of EPIC participants on the factors that contribute to long-term value, and they chose to focus on four key areas and how to measure them:

- Talent: Participants agreed a company’s employees make a big difference when it comes to a company’s ability to create long-term At their best, a company’s employees effectively implement the company’s strategy, apply their skills to help the company navigate disruption, and bring new ideas to the table. Project participants focused on metrics for reporting on how effectively human capital deployment, organisational culture and employee health could influence a company’s long-term prospects;

- Society and environment: Participants also recognised that, increasingly, companies must earn their “license to operate” in society in order to be successful in the long-term. But despite this growing consensus, the conversation around societal value has remained relatively Businesses still have difficulty quantifying the societal value they create. This was the challenge one working group sought to confront using the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a basis for their work;

- Corporate governance: There is, of course, already a great deal of disclosure around corporate However, as boards become more involved in strategic planning, investors say that very little of it enables them to gauge whether the board is equipped to help shape a business’s long-term strategy and value; and

- Innovation and consumer trends: There is a simple truth at the heart of every business: if people don’t want to buy what the business sells, there is no way it can survive. Therefore, participants agreed that it was critical to measure areas that impact whether consumers and other stakeholders are likely to interact with a company. Is the company innovating to keep up with evolving demands? Do people trust it? Do its products and services impact people’s health? All of these factors help gauge whether the company is positioned to stay relevant over the long-term.

Stewardship—a new template for reporting

Our review revealed that a broad range of stewardship reporting styles and approaches are currently being applied by institutional investors. As mentioned earlier, many investors rely on case studies (often anonymised) to provide examples of their engagement activities and the outcomes they achieved, but it is not always clear if or indeed how they relate to the investor’s stewardship activities on the whole.

A smaller group of investors broke down the frequency with which they engaged with business on particular priority areas. We believe that this, combined with detailed case studies, may offer a useful template for best practice in stewardship reporting, enabling greater consistency and richness of insight as the area continues to evolve.

Trust and reputation—the move towards measurement

Despite the strong link between long-term value creation and how businesses are perceived by stakeholder groups, we observed scant evidence within their reporting of investors directly engaging on how businesses measure and manage reputation and stakeholder trust. There is a clear opportunity for businesses to differentiate their brands along these lines, with a majority of Britons (52%) believing that the way business works is not good for British society, and 79% stating they expect CEOs to take the lead on change rather than waiting for government to impose it.25 Technology and frameworks are available to support businesses in assessing and managing how they are perceived by the stakeholder groups on which their long-term success depends. Investors should actively engage with investee companies on how to best leverage these.

Corporate reporting—regulatory pressures mount

Corporate reporting is a critical component to improving corporate accountability. Over the coming months, we expect greater regulatory and policy focus to be applied to the scope and quality of corporate reporting, given its relationship to the several independent and regulatory reviews currently underway in the UK. These include the Financial Reporting Council’s Review of the Future of Corporate Reporting and the Brydon Independent Review into the Quality and Effectiveness of Audit. Through their stewardship activities, investors are in a perfect position to shape how corporate reporting is redefined in ways that both improve transparency and support the safe investment of capital for the long-term.

Audit and assurance—expectations set to rise

In our research, audit and assurance received a relatively low stewardship priority score of 1.36, but we expect this to change as corporate reporting expectations rise and investors increasingly engage on the issue.

This is set against a background in which recent corporate and audit failures in the UK have led to a heightened regulatory, government and media scrutiny of audit and the audit

market, with significant reform expected. As the ultimate beneficiaries of audit, and in light of the role of stewardship in strengthening corporate accountability, institutional investors are likely to continue to come under greater pressure to demonstrate the frequency, depth and effectiveness of their engagement around audit and assurance. We expect that dialogues with boards will continue to evolve in this regard, leading to an increase in the priority score in the near future.

* * *

The complete report, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print