Matteo Tonello is managing director of corporate leadership at The Conference Board. This post relates to an issue of The Conference Board’s Director Notes series authored by James D. C. Barrall, David T. Della Rocca, Carol B. Samaan, Julie D. Crisp, and Michelle M. Khoury.

In light of increased transparency and governance expectations imposed by shareholder advisory groups and increasingly aggressive attempts by plaintiffs’ firms to enjoin shareholder votes on key compensation issues, U.S. public companies face a substantial burden to provide adequate disclosure in their annual proxy statements. This Director Notes examines the key disclosure issues and challenges facing companies during the 2013 proxy season and provides examples of company responses to these issues taken from proxy statements filed during the first half of 2013.

U.S. public companies face a substantial burden to provide adequate disclosure in their annual proxy statements. In addition to complying with a growing number of increasingly burdensome disclosure rules from Congress and the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), companies must take into account corporate governance guidelines from institutional shareholder advisory groups such as Institutional Shareholder Services (“ISS”) and Glass Lewis & Co. Moreover, a recent wave of proxy injunction lawsuits has added to this burden and created additional issues and challenges for companies. The plaintiffs’ bar has also been actively pursuing damage claims against public companies based on disclosure and corporate governance issues, including issues relating to Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”). All of these developments present many traps for the unwary. As a result, companies should review their executive compensation disclosure and their say-on-pay and equity plan proposals to determine whether additional disclosures, beyond those required by statutes and rules, are appropriate to attempt to reduce the risk of a potential lawsuit or investigation by a plaintiff’s law firm.

The following post discusses the key disclosure issues faced by public companies during the 2013 proxy season, and it offers examples of how companies have responded with disclosure examples taken from proxy statements filed during the first half of 2013. [1]

Proxy Injunction Lawsuits

A string of shareholder lawsuits and investigations has emerged seeking to enjoin companies from holding shareholder votes, including votes on say-on-pay and equity plan proposals, unless and until shareholders are provided with additional information. [2] Any public company holding a shareholder say-on-pay vote or equity plan vote may be subject to such lawsuits and investigations, which are modeled after allegations of breach of fiduciary duties and material omissions commonly found in litigation relating to mergers and acquisitions. Emboldened by early successes, plaintiffs’ firms appear to be after quick settlements, with amounts ranging from approximately $200,000 to $600,000, resulting in the payment of attorneys’ fees to the plaintiffs, but few additional meaningful disclosures.

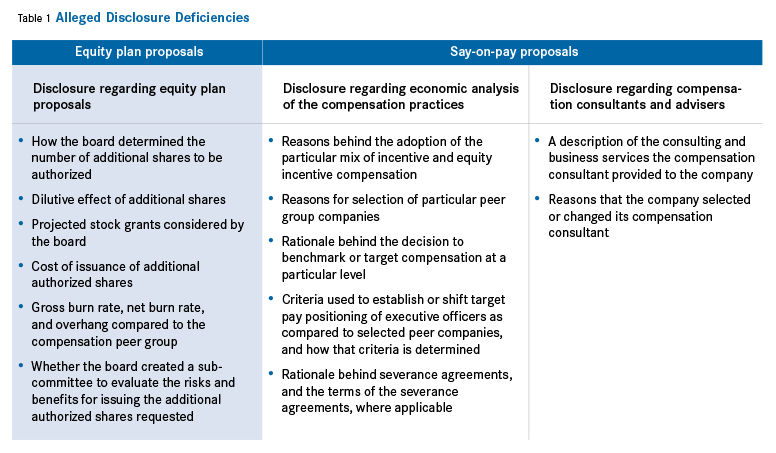

Background: The proxy injunction lawsuits have been based on allegations that the disclosure regarding compensation-related proposals is deficient, inadequate, and/or misleading (principally, the disclosure related to say-on-pay and equity plan votes). Specifically, the lawsuits claim that the directors breached their fiduciary duties by making materially deficient disclosure to shareholders and ask the court to enjoin the shareholder vote until the company provides additional disclosure. In some instances, the lawsuits also allege corporate waste and breach of fiduciary duties if the company’s public disclosure reveals grants to executives in excess of the equity plan’s share limits (either the aggregate share limit, full value award limit, or per participant award limit).

Dozens of these lawsuits have been filed since October 2012, and plaintiffs’ firms have announced a multitude of informal investigations. The announcement of an investigation is designed to attract shareholders to volunteer as plaintiffs and spearhead the class action lawsuits. Many of these lawsuits have been filed by Faruqi & Faruqi LLP. While the general consensus in both the legal and business communities is that these lawsuits are frivolous, companies are concerned that their proxies could be targeted, especially since these lawsuits tend to seek detailed and minor disclosures that historically have not been found in proxy statements.

The issues typically alleged in these lawsuits include the following items.

Analysis of 2013 Proxy Disclosure

Based on a sampling of proxy statements filed by public companies with at least $2 billion in revenue during the first half of 2013, it appears that an increasing number of companies are providing shareholders with additional or enhanced disclosures, which are likely in response to this new wave of litigation.

Changes to peer group companies

Many companies highlighted changes to their peer group companies in graphics or tables that provided detailed explanations of the reason for any changes (e.g., omitting prior peer companies, adding new ones, and their processes for selecting their peer groups). The following examples reflect this enhanced disclosure.

- COMPANY A

“The compensation committee, with assistance from [compensation consultant], annually reviews specific criteria and recommendations regarding companies to add or remove from the comparator group. The committee’s primary selection criteria are industry (specialty retail, consumer products, and restaurants), size (revenue and market capitalization), and geography or scope (global reach); secondary selection criteria are brand recognition, performance (revenue growth, earnings per share growth, and total shareholder return growth), as well as other considerations, including companies with which we compete for executive talent or customers, and companies known for innovation. As a result of the committee’s review in June 2012, [peer company] was removed from the comparator group. Although the compensation committee prefers to keep the comparator group substantially the same from year to year, the committee believes such adjustments are occasionally warranted so that our comparator group companies remain aligned with the company’s strategic plan.” - COMPANY B

“Based on the compensation committee’s review, with input from our independent compensation consultant, the compensation committee removed companies from the 2012 peer group for the following reasons: low growth and market capitalization, low market cap to revenue multiples as compared to ours, being situated outside of our industry, and acquisitions. The compensation committee added companies to the 2013 peer group for the following reasons: recent public offerings, similar industry space, and similar market cap to revenue multiples.” - COMPANY C

“In the fall of 2012, the committee reviewed and updated its peer group (we refer to the updated peer group as the 2013 peer group) by removing [company] (acquired during 2012) and [company] (comparably too small) and adding [companies]. To identify the additions, the committee considered the historical market capitalization, financial performance and executive compensation of companies not included in the 2012 peer group but identified as peers by the largest of the proxy advisory services. The financial metrics at the median of the 2013 peer group are intended to approximate, on balance, the company’s financial metrics.”

Factors the board considered in approving an increase in shares under an equity plan

A recent disclosure trend has been to include more detailed information regarding how the board set the number of shares to be authorized and why the new plan or amendment is in shareholders’ best interest. This additional disclosure is often placed near the beginning of the equity plan proposal to highlight the information supporting the company’s request for new or additional shares. While shareholders generally would be able determine the facts included in these disclosures from the company’s proxy tables and compensation discussion and analysis, these disclosures distill the data and present it prominently and in narrative form. We believe that this type of enhanced disclosure will become more common. The following examples illustrate the considerations weighed by companies and boards requesting additional shares under the equity plans, focusing on historical and current equity award practices and recommendations by the compensation committee’s compensation consultant.

- COMPANY A

“(1) If we do not increase the share reserve at our 2013 annual meeting, we would need to make significant changes to our equity award practices in order to conserve the share reserve balance until the time of our 2014 annual meeting. The changes to our practices would limit our flexibility to provide competitive compensation and thus our ability to attract, motivate and retain highly qualified talent. (2) If our stockholders approve our request for … additional shares at the 2013 annual meeting, we believe this amount will be sufficient for two to three years. (3) We have decreased our annual equity burn rate and dilution by granting restricted stock units and performance stock units as components of our broad-based equity program.” - COMPANY B

“The board of directors and the compensation committee carefully considered the compensation needs of the company as well as the company’s historical equity compensation practices in determining the number of shares to be subject to the 2013 plan. This analysis included reviewing the company’s past equity compensation practices and assessing the number of shares likely to be needed for future grants … the company’s independent compensation consultants assisted in the analysis.” - COMPANY C

“Based on current projections, without increasing the number of shares available for issuance under the [plan], the company will be unable to grant equity awards to employees, as part of our next ordinary course annual equity award cycle, in amounts consistent with past practice… Because the company intends to continue issuing annual equity and off-cycle equity awards to key employees consistent with past practice, the number of shares available for issuance under the plan … is not sufficient to issue the company’s fiscal 2013 off-cycle equity awards and the fiscal 2014 annual equity awards scheduled for issuance in December 2013. In evaluating the company’s request to increase the number of shares available for issuance under the [plan], the compensation and human resources committee of the board (the “committee”) considered the number of shares required to continue making annual equity awards at levels consistent with prior practice and market conditions and the impact that the additional shares requested will have on the company’s dilution and overhang ratios. After concluding its evaluation, the committee recommended to the full board the amended and restated [plan], including the increase in the number of shares available for issuance, which the board adopted and approved for inclusion in this proxy statement.”

Historical burn rate, overhang and dilution metrics

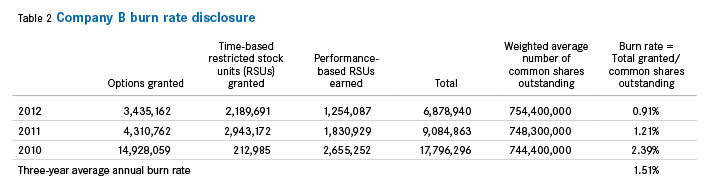

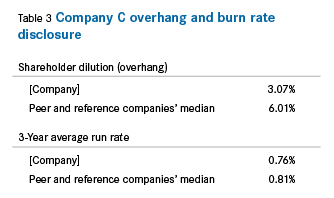

Companies provided more information regarding historical burn rate, overhang and dilution and discussed their equity grant practices to make their case for shareholder approval of an increase in the number of shares available for issuance under their equity plans. A number of companies provided this information in tabular format, along with a narrative explaining how each metric was derived and/ or its significance. A smaller number of companies provided comparisons of their historical burn rate, overhang, and dilution information to their peer companies. The following examples illustrate this type of disclosure.

- COMPANY A

“Our potential dilution, or ‘overhang,’ from outstanding awards and shares available for future awards under the 2013 plan is approximately 10.1 percent. This percentage is calculated on a fully diluted basis, based on the total shares underlying outstanding stock-based awards (65,280,836), the shares available for future awards under the 2013 plan (55,000,000) and the total shares of company common stock outstanding as of February 4, 2013 (1,069,292,165). The average ‘burn rate’ for awards that we granted in the last three fiscal years is 1.55 percent. ‘Burn rate’ is the number of awards granted (stock options and restricted stock units) divided by the weighted average number of common shares outstanding. We calculated our burn rate by applying a multiplier of two to the number of restricted stock units granted based on our stock price volatility. The median burn rate for Russell 3000 companies in the materials sector, published by Institutional Shareholder Services Inc., is 1.63 percent.” - COMPANY B

“As shown in the following table, the company’s three-year average annual burn rate was 1.51 percent, which is below the Institutional Shareholder Services (“ISS”) burn rate threshold of 3.88 percent applied to our industry.” - COMPANY C

In the following table, the reporting company compared its overhang and burn rate percentages to the median percentages of its peer companies:

Projected (future) burn rate, overhang, dilution and length of time shares are expected to last under equity plan

Some companies disclosed estimates of how long the additional shares requested under the equity plan are expected to last. However, such disclosure appeared to be less common than disclosure on historical burn rate, overhang, and dilution metrics, presumably because of the difficulty in forecasting such numbers, and because boards and compensation committees are less likely to focus on this issue than on historical metrics, which affect the number of shares that proxy advisers and shareholders are likely to support. It is also important to note that providing future projections may serve as a potential target for plaintiffs in future years if those projections are not accurate. Accordingly, careful consideration should be given to such disclosures. Many companies attempted to qualify future projections by indicating that future projections are based on historical or current equity practices and burn rates, and that they are subject to change at the company’s discretion. The following examples show this type of disclosure.

- COMPANY A

“Based on the company’s past practices, the board of directors anticipates that the 2013 plan, including both the 9,500,000 shares allocated to the 2013 plan, as well as the shares remaining in the 2011 plan, will suffice for grants for the next four years. The company has previously adopted stock incentive plans in 1992, 2000, 2002, 2005 and 2011, so that a four-year horizon is consistent with the company’s past practice. Of course, the actual grants are within the discretion of the compensation committee and conditions in future years may warrant annual grants that are greater or lesser than those in previous years.” - COMPANY B

“The share authorization request under the 2012 plan is a conservative amount designed to manage our equity compensation needs for the next four years, at which time stockholders would be able to reevaluate any additional authorization request. The total potential dilution (including currently outstanding awards) would be approximately 9.26 percent.” - COMPANY C

“Based on our expected annual share usage under all of our equity plans (including those discussed below under ‘Our Other Equity Plans’), we believe our current reserve will be sufficient for our January 2014 grants, but would not be sufficient for our expected January 2015 grants. Our policy is to maintain a reserve at all times sufficient for at least two subsequent annual grant cycles. The board believes that the request for an additional 17.5 million shares will allow us to replenish our share usage under all equity plans during fiscal year 2012 and to continue and maintain our current granting practices through our 2015 annual grants and until our annual meeting of shareholders to be held thereafter in 2015.”

Despite such preventive measures, it should be noted that some companies that provided the type of enhanced disclosures described above were the targets of investigations or lawsuits. Companies should prepare to defend against a lawsuit or investigation by confirming that every material factual statement in the proxy, including any enhanced disclosure related to say-on-pay and equity plan proposals, is defensible and can be supported by the corporate record. In light of the current wave of proxy injunction lawsuits, companies should work closely with their disclosure and litigation teams throughout the year (not just during proxy season) to build sound and defensible corporate records with respect to board and committee actions and appropriate proxy disclosures.

Section 162(m) Compliance and Recent Litigation

Shareholder litigation relating to Section 162(m) of the Code (Section 162(m)) has also increased in recent years. Section 162(m) generally limits the tax deductibility of compensation paid to a public company’s chief executive officer and the next three most highly compensated officers (excluding the chief financial officer) to $1 million, unless the compensation constitutes “qualified performance-based compensation.”

To qualify as “performance-based compensation” under Section 162(m), certain requirements must be met. Among other requirements, the company’s shareholders must approve the “material terms” of the performance goals, including the business criteria on which the goals are based and the maximum amount of compensation payable to any employee, prior to payment of the qualified performance-based compensation. [3] With respect to plans or arrangements that permit the compensation committee to select performance goals based on one or more business criteria approved by the shareholders, shareholder approval must be re-obtained at least once every five years. [4]

Recent shareholder lawsuits filed based on Section 162(m) disclosures in proxy statements have included the following allegations:

- The proxy statement indicates that the compensation paid will receive favorable tax treatment if approved by the company’s shareholders, when that may not necessarily be the case. [5]

- The proxy statement indicates that compensation will be paid regardless of whether the shareholders approve the performance goals, in violation of the shareholder approval requirements under Section 162(m). [6]

- The company failed to include all material terms of the compensation plan or arrangement, or the terms were false or misleading, in violation of the shareholder approval requirements under Section 162(m). [7]

- The compensation committee’s use of discretion to determine the payment of awards violates the requirements of Section 162(m). [8]

Specifically, these complaints claim that the company’s directors intentionally breached their fiduciary duty to disclose all material facts to the company’s shareholders by providing a proxy statement that is “false or misleading,” engaging in corporate waste by paying compensation that could be nondeductible, or engaging in unjust enrichment by failing to pay compensation that is tax deductible under Section 162(m). [9] The lawsuits have typically targeted companies with proxy proposals requesting shareholder approval of a new or amended equity plan or the material terms of the performance goals of a plan. While several lawsuits have been dismissed by the courts at relatively early stages, others have survived motions to dismiss, typically ending shortly thereafter in settlements that provide for the payment of attorneys’ fees to plaintiff’s firms and prohibit companies from granting compensation based on certain shareholder-approved performance goals or business criteria.

The following are general guidelines for drafting equity plans and proxy disclosures based on a review of company proxy statements filed during the first half of 2013:

- State that the plan is “intended” to allow the compensation committee to pay compensation that “may be” exempt under the qualified performance-based compensation exception under Section 162(m) if shareholders approve the plan, rather than stating that such plan or compensation “will be” exempt.

- Avoid stating that if shareholder approval is not obtained, the company “will pay” compensation that is nondeductible. While companies can decide later to pay compensation that is not deductible under other plans and arrangements if shareholders do not approve the plan, such disclosure could be inconsistent with the Section 162(m) requirement that shareholder approval be a condition of qualified performance-based compensation payable under the plan.

- If the proxy proposal is to approve an increase in shares under an existing equity plan, consider stating that, if shareholders do not approve the amended plan, the company can continue to make awards under the existing plan already approved by shareholders, subject to existing authorized share limits (without regard to the increase in shares under the amendment being proposed). The plan’s provisions should also clearly state that if shareholders do not approve the plan amendment, the amendment will not take effect, but that the plan (without regard to the amendment) will continue to be effective according to its terms.

- When discussing the tax impact of Section 162(m), consider stating that the company generally takes into account the deductibility of compensation under Section 162(m) when granting awards, expressly reserving the right to forgo deductibility at the discretion of the compensation committee.

- Avoid stating definitively whether particular awards are or are not deductible because (i) the Section 162(m) rules are complex and sometimes awards are not deductible, even when they are intended to be so, and (ii) even if compensation meets the requirements for qualified performance-based compensation under Section 162(m), plaintiffs may easily contest a company’s factual assertion in a way that could survive a motion to dismiss, leaving it at risk for a shareholder suit.

- Clarify that the compensation committee has only “negative” discretion to decrease the amount of an award intended to be qualified performance-based compensation, if applicable, to prevent plaintiffs from asserting the proxy language is ambiguous as to whether the compensation committee can utilize discretion to increase the amount of an objectively determinable payment, in violation of Section 162(m).

- Clarify that technical operational requirements of Section 162(m) must also be satisfied, in addition to any shareholder approval requirements, in order for plan compensation to be exempt as qualified performance-based compensation.

Companies seeking to avoid such litigation should ensure their plans are compliant with the technical requirements of Section 162(m) and their disclosure is consistent with the Section 162(m) shareholder approval requirements, plan terms and actual practices of the compensation committee.

Director Award Limits under Equity Plans

Many companies allow nonemployee directors to receive equity grants under an equity plan that permits grants to both employees and directors. These are often omnibus equity plans that are designed to qualify awards for the “qualified performance-based compensation” exception under Section 162(m). These plans also include large limits on the number of awards that can be granted to any person, with no special or lower limits for awards to nonemployee directors. Based on a recent ruling in the Delaware case Seinfeld v. Slager, companies should consider whether to include a specific limit (which would be less than the large Section 162(m) limit that would otherwise apply) on the equity awards that can be granted to non‐employee directors under the company’s equity plan and have that limit approved by shareholders. [10] Although the facts in Slager were unusual and the director compensation in question was asserted to be high relative to peer group norms, the court held that directors could not rely upon the business judgment rule when awarding themselves stock under a shareholder approved equity plan that did not have “meaningful limits” in place. [11]

Based on a review of a sample of proxy statements filed during the first half of 2013, it appears that a minority of new plans or amendments to existing equity plans being voted on by shareholders contained a new limit on director equity awards. These award limits were often based on a dollar value calculated using grant date fair value or a flat share limit. Companies only appeared to include such limits in new plans or amendments of existing plans that otherwise would have required shareholder approval. Based on the filings reviewed, companies did not appear to be putting plans up for shareholder approval for the sole purpose of obtaining approval of limits on director awards. Companies should consult with their advisers to determine whether such limits are appropriate, and if so, the amount of the limit.

Compensation Adviser Independence Rules

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 requires that the compensation committee analyze the independence of its compensation consultant and advisers and disclose any conflicts of interest concerning such consultants and advisers.

Item 407(e)(3)(iv) of Regulation S-K codifies the SEC’s proxy disclosure requirement with respect to compensation consultant conflicts of interest, applicable to proxies filed in 2013. [12] As to any compensation consultant who has any role in determining or recommending the amount or form of executive or director compensation, compensation committees are required to assess whether the consultant’s work raises any conflicts of interest and, if so, disclose in the proxy statement information about the nature of any such conflict and how the conflict is being addressed. The rules indicate that the following factors should be considered in determining whether a conflict of interest exists:

- the provision of other services to the company by the person that employs the consultant;

- the amount of fees received from the company by the person that employs the compensation consultant, legal counsel or other adviser, as a percentage of the total revenue of the person that employs the compensation consultant, legal counsel or other adviser;

- the policies and procedures of the person that employs the consultant that are designed to prevent conflicts of interest;

- any business or personal relationship of the consultant with a member of the compensation committee;

- any stock of the company owned by the consultant; and

- any business or personal relationship of the consultant or the person employing the consultant with an executive officer of the company.

While the aforementioned factors should be considered by the compensation committee in assessing whether a conflict of interest exists, the SEC rules do not provide for any materiality or quantitative thresholds with respect to any of these factors. Although no disclosure is required if a conflict does not actually exist, a majority of the proxies we reviewed disclosed that the relationship was reviewed and no conflict of interest was found to exist. The following are examples of this disclosure.

- COMPANY A

“The committee recognizes that it is essential to receive objective advice from its compensation advisors. The committee closely examines the procedures and safeguards that each of its compensation advisors takes to ensure that its compensation consulting services are objective. The committee has assessed the independence of [first consultant] pursuant to SEC rules and concluded that [first consultant’s] work for the committee does not raise any conflict of interest. In making this assessment, the committee took into consideration the following factors:- that the compensation adviser reports directly to the committee, and the committee has the sole power to terminate or replace any of its compensation advisers at any time;

- whether the compensation adviser provides any other services to the company;

- aggregate fees paid by the company to the compensation adviser, as a percentage of the total revenue of the compensation adviser;

- the compensation adviser’s policies and procedures designed to prevent conflicts of interest;

- any business or personal relationships between the compensation adviser, on one hand, and any member of the committee or executive officer, on the other hand; and

- whether the compensation adviser owns any shares of the company’s stock.

In addition, [second consultant] provides compensation advisory services to management to help it develop and execute the company’s overall compensation programs, including evaluating competitive compensation levels and programs for positions below the executive officer level, equity compensation, international compensation, and other issues as requested by [company] human resources. The committee also reviewed [second consultant’s] work for management considering the same factors listed above, and concluded that [second consultant’s] work for management does not raise any conflicts of interest.”

- COMPANY B

“The compensation committee has retained [consultant] as its independent compensation consultant to advise it on all matters related to compensation of our senior management, including our [Named Executive Officers] NEOs. [Consultant] reports directly to the compensation committee and does not provide any other services to our company. The compensation committee believes that there was no conflict of interest between [consultant] and the compensation committee during the year ended December 31, 2012. In reaching this conclusion, the compensation committee considered the factors set forth in Rule 10C-1(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended.”

In addition, effective July 1, 2013, compensation committees are required to perform an independence analysis of their compensation advisers, employing the six factors enumerated above and any other factors they deem relevant. Under New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ listing standards, the requirement to assess the independence of compensation advisers does not apply to advice provided by in-house counsel or any adviser whose role is limited to consulting on certain broad-based plans or providing information that is not customized for a particular company. In approving the new listing standards for both stock exchanges, the SEC made it clear that the independence assessment requirement applies to the selection of (or receipt of advice from) outside legal counsel that provides advice to the compensation committee. In addressing timing, the SEC discussed that the analysis should occur before potential advisers are selected and clarified that it anticipates compensation committees will conduct the independence assessment at least annually. Although a compensation committee is not required to disclose the results of this independence analysis, we anticipate that some companies will provide proxy disclosure to the effect that the relationship was reviewed and no conflict of interest was found to exist.

Realizable Pay

In addition to disclosing the grant date value of pay as mandated by the Summary Compensation Table, several companies (including some large capitalization companies) disclosed “realizable pay,” which generally measures the actual compensation executives could realize (depending on company performance). However, others in the sample of proxy statements reviewed did not include realizable pay disclosure, perhaps waiting to see what trends emerged during the 2013 proxy season.

Realizable pay, which we believe is the most accurate measure of pay, is becoming a more popular measure of pay in the “pay for performance” analysis of public companies. [13] In contrast to realizable pay, pay reported in the Summary Compensation Table relies on grant date values that may over- or underestimate the value of awards or compensation that will actually be delivered to executives.

Based, in part, on the large number of public companies disclosing realizable pay in their proxy statements, ISS indicated in its 2013 policies that it will review realizable pay for large capitalization companies (specifically, S&P 500 companies) in its standard research reports assessing pay for performance. [14] For companies where the initial quantitative pay for performance analysis shows a high or medium level of concern with respect to the alignment of executive pay and company performance, realizable pay will be analyzed over a three-year measurement period compared to Summary Compensation Table pay. [15] ISS’s definition of realizable pay includes the value of cash and equity incentive awards made during a specified performance period. Equity-based awards are calculated based on stock price at the end of the particular performance period. The value of awards will be based on the actual value earned (i.e., the value realized net of any forfeitures, such as due to the failure to meet any applicable performance criteria) or, with respect to awards that are “in progress” or have not yet vested, the target value of the award. Stock options and stock appreciation rights will be revalued at the end of the applicable measurement period using the Black-Scholes option pricing model.

Taking realizable pay into consideration in its pay-for-performance assessment is again a step in the right direction. Ideally, we believe realizable pay should be used in pay-for-performance assessments across the board, rather than confined to a limited group of larger companies and assessed only over a three-year period. Using realizable pay in the pay-for-performance analysis could help uncover underlying alleged or actual causes of pay for performance “disconnects,” which is one of the primary purposes of the pay-for-performance policy, particularly where realizable pay is significantly higher or lower than Summary Compensation Table pay. Using realizable pay in the analysis may reveal that pay and performance are more aligned than the Summary Compensation Table pay otherwise indicates. We will continue to review the impact of ISS’s new policies as more companies are subject to the realizable pay aspect of ISS’s pay-for-performance assessment. As trends emerge, we anticipate that more companies will voluntarily include some form of realizable pay disclosure in their proxy statements.

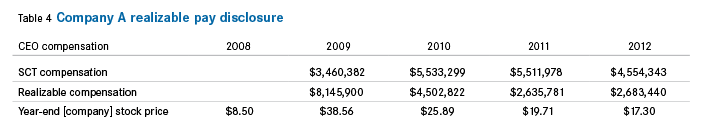

The following are some examples of realizable pay disclosure, which is also often summarized in tabular or chart format.

- COMPANY A

“[Table 4] shows both “realizable” compensation and compensation as set forth in the Summary Compensation Table of this and prior years’ proxy statements. Both realizable compensation and compensation set forth in the Summary Compensation Table show the actual amount of salary and bonus earned. Realizable compensation differs from compensation shown in the Summary Compensation Table in the way that equity-based awards are valued. As required by the SEC, the Summary Compensation Table shows the fair value of stock awards and option awards as of the date of grant, calculated in accordance with accounting rules. These amounts represent the company’s accounting expense for these grants. The amounts do not reflect the actual number of performance-based RSUs earned based on corporate performance and, for both RSUs and stock options, do not take into account changes in the company’s stock price after the date of grant, both of which factors affect actual compensation earned. Realizable compensation takes both of these factors into account.For the realizable compensation shown [Table 4] below, the value of performance-based RSUs was calculated by multiplying the actual number of RSUs earned in respect of a year by the price of [company] stock as of December 31 of that year, and stock options were valued at their “in the money” value at December 31 of the year in which they were granted. The company believes that realizable compensation is more representative of compensation actually earned than is the compensation shown in the Summary Compensation Table and that realizable compensation is therefore the better measure of compensation to compare against corporate performance.” - COMPANY B

“Our executive compensation program design is intended to be competitive and to link executive compensation outcomes with performance. To ensure that our pay-for-performance philosophy translates into real outcomes, the committee’s independent compensation consultant, [consultant], tested that linkage. [Consultant] reviewed (a) realized compensation, or the value of the compensation actually received, by our CEO for the years 2010-2012; (b) realized compensation of the CEOs of our peer group, calculated on the same basis using data disclosed in their proxy statements and (c) the total shareholder return (“TSR”) for us and our peers over the 2010-2012 period. The primary purpose of this review was to determine if our performance and our CEO’s compensation are aligned with companies in our peer group for this three-year period.The committee determined that this analysis … demonstrates that for the period measured, the correlation between performance and CEO realized compensation is in line with our peers.Realized compensation is different than compensation as disclosed in the Summary Compensation Table on page 37. Among other things, the Summary Compensation Table analysis, the format of which is standardized by SEC regulation, values long-term equity grants at the date of grant based on a presumed or predicted future value. A realized compensation analysis, on the other hand, measures the value of long-term compensation as it is earned rather than the value at the time of grant. We encourage you to consider our analysis in light of the information included in the Summary Compensation Table … and the subsequent tables.”

Conclusion

As a result of heightened expectations by proxy advisors related to the corporate governance practices and transparency of disclosures made by public companies, and increasingly aggressive attempts by plaintiffs’ firms to enjoin shareholder votes on key compensation issues, companies should review their 2013 proxy statements, the results of shareholder votes, any recommendations by proxy advisory firms, and overall proxy disclosure trends, to determine whether and, if so, what additional disclosures may be warranted as they prepare to draft their 2014 proxy statements.

Endnotes:

[1] Disclosure examples cited were taken from proxy statements of public companies with at least $2 billion in revenue filed with the SEC between January and June 2013. Company names have been omitted.

(go back)

[2] See James D.C. Barrall, “Update on Proxy Vote Injunction Lawsuits and Investigations,” The Conference Board Governance Center Blog, February 5, 2013 (http://tcbblogs.org/governance/2013/02/05/update-on-proxy-vote-injunction-lawsuits-and-investigations/).

(go back)

[3] Treas. Reg. § 1.162-27(e)(4)(i).

(go back)

[4] Treas. Reg. § 1.162-27(e)(4)(vi).

(go back)

[5] See, e.g., Seinfeld v. O’Connor, 774 F. Supp. 2d 660, 666–667 (D. Del. 2011); Hoch v. Alexander, U.S. Dist. LEXIS 71716 (D. Del. July 1, 2011).

(go back)

[6] See, e.g., Shaev v. Saper, 320 F.3d 373, 381 (3d Cir. 2003).

(go back)

[7] See, e.g., O’Connor, 774 F. Supp. 2d at 665.

(go back)

[8] See, e.g., Shaev, 320 F.3d at 381.

(go back)

[9] See Abrams v. Wainscott, Case No. 11-297-RGA (D.C. Del. Aug. 21, 2012); Hoch, U.S. Dist. LEXIS 71716 at *6–7.

(go back)

[10] Seinfeld v. Slager, 2012 WL 2501105 (Del. Ch. June 29, 2012).

(go back)

[11] Directors were granted equity awards exceeding $800,000 in value in one fiscal year.

(go back)

[12] Securities and Exchange Commission Final Rule, “Listing Standards for Compensation Committees,” adopted June 20, 2012, effective July 27, 2012.

(go back)

[13] James D. C. Barrall, Alice M. Chung, and Julie D. Crisp, “Defining Pay in Pay for Performance,” The Conference Board, Director Notes, 4, no. 18, September 2012.

(go back)

[14] Gary Hewitt and Carol Bowie, “Evaluating Pay for Performance Alignment: ISS’ Quantitative and Qualitative Approach,” December 2012, revised January 2013 (www.issgovernance.com/sites/default/files/EvaluatingPayForPerformance.pdf).

(go back)

[15] Hewitt and Bowie, “Evaluating Pay for Performance Alignment.”

(go back)

Print

Print