Matthew Schoenfeld is a Portfolio Manager at Burford Capital. This post is based on his recent paper, and is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

This paper considers the ramifications of the Delaware Supreme Court’s December 2017 Dell appraisal decision within the context of Delaware’s more sweeping clampdown on shareholder litigation protections in recent years, beginning with Corwin in 2015.

In addition to lower deal premia and higher agency costs, the primary effects of Delaware’s post-2015 effort to dull shareholder defenses, culminating in Dell, will likely be: 1) faster CEO pay growth, and 2) more M&A and higher industry-specific measures of concentration, which research has shown to contribute to declining competition, lower levels of labor market mobility, wage stagnation, and increasing inequality in the United States.

The Road to Dell

The path to Dell begins with Corwin, a 2015 decision that limited the number of transactions subject to enhanced scrutiny under Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc. Corwin degraded shareholders’ ability to get discovery on the back-end by empowering defendants to stonewall requests for transparency on the basis of a ratifying shareholder vote, essentially rendering fiduciary duty litigation toothless as a means of exposing bad actors after the fact.

Corwin’s pinioning of ex-post shareholder discovery was then coupled with an effective narrowing of shareholders’ ex-ante defenses, with Trulia, a January 2016 decision which held that the Delaware courts would no longer countenance merger litigation settlements that did not achieve meaningful benefits for shareholders.

Because plaintiffs often do not know in advance whether discovery will yield information that can generate a settlement with meaningful benefits, Trulia substantially decreases the expected value of bringing a claim. As a result, filings in Delaware fell by nearly 50% in 2016, while the dismissal rate for deal-related litigation, which averaged 24% from 2010-2014, rose to 89% in 2017.

The “death” of fiduciary duty litigation—in the wake of Corwin and Trulia—made remaining shareholder defenses dearer, particularly the appraisal remedy, which became petitioners’ last line of defense for exposing conflicted actors via access to a fulsome discovery process.

But despite the appraisal remedy’s enhanced importance for shareholders, an effort to discourage appraisal litigation gained substantial momentum in the latter-half of 2016. In August of that year, reforms to the Delaware appraisal statute—intended to make appraisal less economically attractive—took effect, followed shortly thereafter by a slew of at-or-below merger price appraisal opinions.

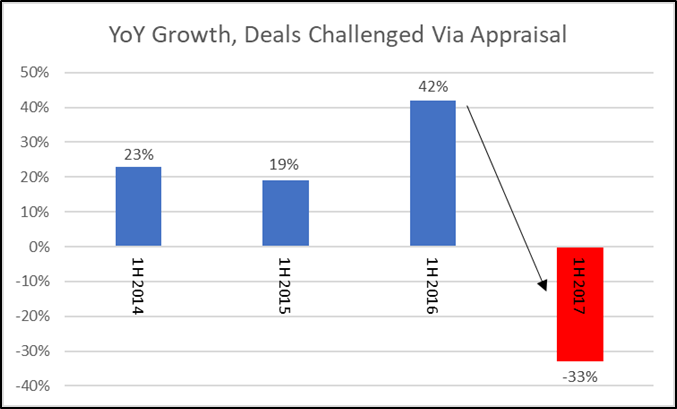

The result has been that fewer deals are being challenged via appraisal. During the first half of 2017, eighteen deals were challenged, one-third fewer than the twenty-seven challenged during the same period in 2016.

Those seeking curtailment of the appraisal remedy in Delaware had argued that the presence of appraisal-seeking holdouts induces buyers to withhold top dollar. On their view, curtailment of appraisal should have sent premia upwards as buyers used more of their powder for bids.

But the opposite happened: In 2017, after statutory and judicial efforts to make appraisal less effective caused a decline in filings, the average U.S. target premium of 22.5% was the lowest of any year since at least 2005.

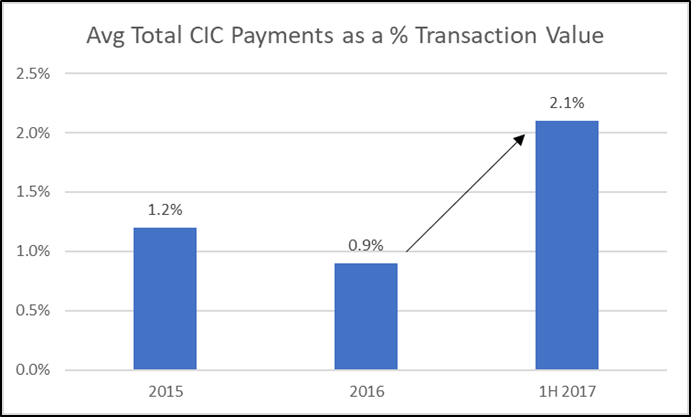

Another impact of the fall in appraisal filings was an uptick in managerial agency costs. In 1H 2017, average “golden parachute” compensation was 2.1% of transaction equity value, up 52% from its 2012-2016 average of 1.36%.

These two effects—falling premia and rising parachutes—are likely related. The prospect of appraisal, because it includes discovery that can unearth bad behavior, makes target managers more reluctant to push for low-price sales to favored acquirers in exchange for a plum post-sale position or a sweetened exit package. As the prospect of appraisal evaporates, so will this reluctance.

Dell: Finishing what Corwin Started

The appraisal remedy, already weakened, suffered a more permanent blow on December 14, 2017, when the Delaware Supreme Court reversed and remanded the Chancery’s May 2016 Dell appraisal ruling. The Dell reversal followed August’s DFC Global opinion, in which the Supreme Court reversed another premium-to-deal-price Chancery ruling.

Dell’s guiding principle and broader public policy objective was to promulgate the primacy of process in deals which adopt “best practices” at the front-end. At the fore of the “best practices” lauded in Dell was a purportedly “robust sales process” on the back of which the Court mandated a “strong reliance upon the deal price and far less weight, if any, on the DCF analyses.” In doing so, the Court, for all intents and purposes, established a procedural safe harbor for third-party transactions with “robust sale processes.”

The net impact is that deals which appear procedurally “clean,” as sketched out by the transacting companies in their proxy materials, will escape closer scrutiny moving forward because shareholders are now boxed in by the one-two punch of Corwin’s ratifying shareholder vote and Dell’s de facto procedural safe harbor.

Wishing it Doesn’t Make it so: “Best Practices” Doesn’t Mean Fair Dealing

The efficacy, as well as the public policy coherency, of Dell is tied to the notion that procedural “best practices” lead to, or are reflective of, fair dealing. But, oftentimes, that link doesn’t hold.

“Best practice” is a subpar gauge of propriety because the actors most likely to be conflicted are also the ones most likely to be in control the narrative presented in public-facing materials.

For a lens into the details often omitted from public-facing materials, consider a recent appraisal case challenging the 2016 sale of Towers Watson to Willis Group.

In that case, a Motion to Compel hearing led to the public disclosure of internal documents of a large Willis Group investor alleged to have had undisclosed contact with Towers Watson’s CEO. The publicly released documents appear to show that the Willis Group investor offered Towers Watson’s CEO a three-year pay package worth up to $140 million during an undisclosed meeting just two months before a contested shareholder vote and a subsequent renegotiation of merger terms which he spearheaded.

Or, consider last year’s Clearwire appraisal opinion, which revealed a previously undisclosed quid pro quo between Softbank’s founder, chairman and CEO, Masayoshi Son, and Paul Otellini, then-CEO of Intel.

An obvious risk of codifying standards for deference ex-ante is that it will incent bad actors to conceal more, not less, information. Specifically, with the guidelines for effectively eliminating appraisal risk neatly sketched out, it will prove beneficial for conflicted actors to disguise “dirty” deals as clean in proxy materials because while such subterfuge wouldn’t withstand a robust discovery process, a façade of propriety will discourage appraisal petitioners weary of deference, thus rendering discovery moot.

Reflecting on this point, an article published last summer by Hon. Sam Glasscock III comes to mind. The Vice Chancellor contends that utilizing valuation techniques, as opposed to deferring to deal price, in the appraisal of “clean mergers” does little to encourage more efficient capital markets: “I find little to recommend extending an appraisal right to dissenters in the case of a “clean” merger.”

But, respectfully, the problem with restricting the extension of the appraisal right in “clean mergers,” as the Vice Chancellor suggests, is that it’s impossible to know if a merger is “clean” before discovery. Shareholders must rely on the proxy materials provided to them by the company when deciding whether to petition for appraisal and per the examples above, these materials can leave out details which might be germane for determining cleanliness.

In the Post-Dell era, the dirtier the reality, the greater the incentive to present a “clean” appearance to minimize the probability of that dirt ever being exposed.

From Corwin to Dell: Higher CEO Pay, More Deals, but at what Cost?

In addition to lower deal premia and higher agency costs, the primary effects of Delaware’s post-2015 effort to dull shareholder defenses, culminating in Dell, will likely be faster CEO pay growth and more M&A.

Burgeoning golden parachutes, a result of pinioned shareholder deterrents, not only enrich departing executives but, logically, they also pressure going-concern CEO compensation upwards. Negotiating leverage for incumbent CEOs is enhanced because the alternative of a sale is commensurately more attractive than it was previously due to the increased rents able to be extracted thereby, thus challenging boards to meet or exceed the net present value of these newly-available rents when structuring go-forward compensation.

“More deals,” the second first-order effect, refers specifically to those deals which would not otherwise occur without the rent-seeking opportunities afforded by dulled shareholder deterrents and weakened oversight.

The winners from this inorganic uptick in deal activity are the usual suspects—CEOs and their advisors—but the losers potentially extend well beyond minority shareholders.

Research conducted by President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors suggests that by bolstering already high industry-specific measures of concentration and market share, M&A can contribute to declining competition, lower levels of labor market mobility and business dynamism, wage stagnation, and increasing inequality in the United States.

While guarding against these adverse, anticompetitive, impacts, can and should be the province of federal antitrust authorities, they are inherently limited by the statutory scope of antitrust merger reviews and cannot consider many of the adverse social consequences of mergers.

Indeed, the incremental subset of M&A driven by enhanced rent-seeking opportunities post-Dell is likely to be particularly damaging with respect to its impact on industry-specific measures of concentration.

Namely, underperforming CEOs—those “underwater” with respect to their performance-based stock grant thresholds—are particularly likely to initiate self-serving sales processes due to the automatic vesting provisions which typically accompany change in control transactions. Because the selling parties are disproportionately “underperformers,” sales to strategic parties tend to result in the strong, “outperformers,” becoming stronger.

None of this is to say that M&A is “bad” for society. Rather, it’s to acknowledge that M&A has real social costs. Unfortunately, the additional, “inorganic,” rent-seeking transactions enabled post-Dell will entail even greater social cost, with few of the redeeming social benefits of “organic” M&A aimed at creating, rather than reallocating, value.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print