Gabriel Rauterberg is Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Michigan Law School. This post is based on a review essay in the Harvard Law Review.

The last two years have seen astonishing changes to how public institutions manage the economy in the United States and other developed countries. Like so many recent changes, this began in March 2020, when the world faced not only a public health emergency but also one of the most profound shocks to the global economy in the modern era—a shock broader than any other in eighty years. Never before had virtually all of the world’s economies suffered a contraction at the same time. Global output decreased by nearly 3.4% in 2020, the largest contraction since the Second World War. The United States saw the largest recorded demand shock in its history (-32.9%), and the unemployment rate peaked around 15% during 2020.

In response, the United States, European Union, and dozens of other governments embarked on massive campaigns of economic stimulus. Over a year and a half, the United States Congress spent almost $5 trillion across three major fiscal packages. Just the first of those bills, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (or “CARES Act”), at $2.2 trillion, was already twice the size of the Obama Administration’s principal response to the Great Recession, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. The European Union likewise engaged in massive fiscal stimulus, also outpacing its response to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (“GFC”). For a wide range of nations, this has led to the largest expansion of government spending—and associated fiscal deficits—relative to the economy’s size, since World War II. Indeed, the urgency and scale of the fiscal response to Covid-19 drew analogies to war finance, as opposed to more traditional forms of business cycle management.

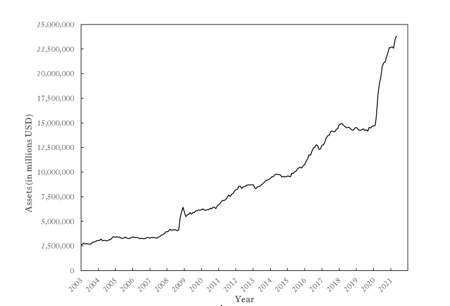

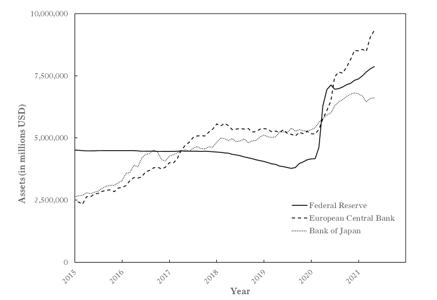

Another arm of those nations’ governments, their independent central banks, similarly engaged in financial intervention on a scale not seen in eighty years. In 2003, the total assets held by the three largest central banks in the developed world—the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, and the Federal Reserve or “Fed” (the central bank of the United States)—added up to roughly $2.5 trillion. As Figures 1 and 2 show, the GFC led those banks’ balance sheets to more than double in size. But even against that backdrop, the growth since the coronavirus is astonishing. Those three central banks now hold almost $25 trillion in assets. That significantly exceeds the total assets of the United States’ commercial banking sector, which holds about $22 trillion in assets. Over roughly a year, the Federal Reserve alone doubled its asset holdings from around $4 trillion to $8 trillion, making for arguably the most aggressive expansion of the United States’ money supply since the Federal Reserve’s founding in 1913.

Figure 1: Growth in Total Assets of the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, and Bank of Japan (“Central Bank Assets”) Since 2003

Figure 2: Growth in Central Bank Assets Since 2015

The sheer scale of these monetary and fiscal interventions is staggering, and the level of governmental spending represents a sharp break from once-dominant macroeconomic orthodoxies. These changes to the practice of fiscal policy and central banking raise fundamental questions about the design of the institutions through which governments intervene in and manage the economy. What does the scale, character, and complexity of central banks’ interventions tell us about those banks’ appropriate objectives and design? And we have named only two parts—the Treasury department and central bank—of the modern state’s vast governmental apparatus. Alongside fiscal policy and central banks, what is the role of the rest of the legal system in addressing economic crises and recessions?

In a recent book review essay, Josh Younger and I analyze these events through the prism of Professor Yair Listokin’s Law and Macroeconomics: Legal Remedies to Recessions and Professor Adam Tooze’s Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy. While widely different, the books share a willingness to probe basic issues of institutional design and a capacity to shed light on the questions above.

In Law and Macroeconomics, published in 2019, Listokin asks us to imagine that we are in a deep recession, and that the traditional macroeconomic tools for responding to that recession have reached their limits—central bankers have vigorously deployed monetary policy, while Congress is either unable or unwilling to provide further fiscal support and stimulus. Listokin asks: Can the rest of the legal system—judges, juries, the regulators of the vast administrative state—do anything more about the recession? Should they? If so, what?

Listokin’s principal argument is that there is a valuable but overlooked third option in the policy toolkit—which he calls “expansionary legal policy”—the use of courts, administration, and regulation to further stimulate overall demand for goods and services during recessions. In effect, the book suggests, all legal officials with discretion should exercise that discretion with macroeconomic objectives in mind, including the goal of providing stimulus during recessions.

Shutdown, published late in 2021, focuses on the economic effects of the Covid crisis in the immediate year following the pandemic’s arrival. It combines that narrative with an ambitious effort to characterize the crisis conceptually, to situate it in history, and to lay a foundation for learning its lessons about how the global economy and its governance have changed. Through a wide-ranging blend of politics, economics, and social critique, Adam Tooze situates the massive fiscal and monetary interventions of the Covid-19 era in these broader contexts. A centerpiece of the book is a vivid narrative of the near-collapse of the U.S. treasury market in March 2020, and the spectacular response of the Federal Reserve to those dislocations (pp. 111–54).

This Review’s approach, in essence, is to analyze the framework of the first book through the events narrated by the second. Along the way, it offers a brief primer on the financial dislocations as well as the monetary and fiscal innovations of 2020. We develop Law and Macroeconomics’ vision of expansionary legal policy, by applying it to the events of 2020, using Shutdown as our narrative and analytical guide. We provide two in-depth case studies of “law and macroeconomics” in action. First, the “interim final rule” through which the Fed temporarily suspended certain fundamental capital structure restrictions on banks. Roughly, the Fed released commercial banks from restrictions that they maintain capital for riskless assets, like Treasuries. Second, we analyze the asset cap that the Fed imposed on the global megabank Wells Fargo, which was intended to enforce standards of conduct, but also limited Wells Fargo’s ability to provide credit to financial markets during the crisis. One is an example of expansionary legal policy and the other of its opposite.

These case studies illustrate our main claims about expansionary legal policy. First, that Listokin’s “law and macro” framework is both useful and amenable to substantially more development. Second, that during a recession arguably the most powerful institution in the legal system for exercising discretion to stimulate demand is the regulation of commercial banks. That said, more precision is necessary, particularly given the checkered history of ad hoc regulatory flexibility (for example, the S&L crisis and Japanese banking crisis). Expansionary legal policy is not always good policy, and we begin to sketch an analytic framework through which to consider when and how banking regulators should exercise discretion as expansionary legal policy.

In effect, our core question is: When should banking regulators use their administrative discretion to stimulate aggregate demand? This stimulative exercise of discretion usually takes the form of capital forbearance: a policy of either explicit or de facto reductions in bank capitalization requirements that frees banks to grow in size and activity.

Looking at past exercises of stimulative discretion by bank regulators that plausibly failed, we see two key characteristics. First, they were crises that originated in the financial sector, not the real economy. Second, regulatory forbearance was focused on risk-based capital requirements, not leverage or other size-based measures. Once we see these characteristics clearly, the failure of forbearance policies in both the United States and Japan is not terribly surprising. Financial crises are often the result of a structural mispricing of credit risk. Policies that delay the process of resolving that inefficiency can lead to the misallocation of resources and poor support to aggregate demand. As history shows, they may make the problem worse.

The temporary capital relief offered by the Federal Reserve in April 2020 stands in sharp contrast. As the Federal Reserve rapidly expanded its balance sheet amidst a “dash for cash” by a wide range of economic and financial market participants, the rapid and largely involuntary accumulation of risk-free assets threatened to crowd out some forms of credit creation as banks were increasingly bound by leverage. In the meantime, banks had entered the crisis in a very strong position from both a risk-based capitalization and liquidity standpoint. Thus, the Fed’s intervention was designed to sever the link between capital requirements and bank size to allow for more rather than less efficient price discovery, and thus to support aggregate demand.

Taken together, our historical examples help us suggest a framework for thinking about expansionary banking policy. Capital forbearance has its place but is safest when two conditions are met. First, the shock should be nonfinancial in origin, suggesting an ex ante healthy banking sector. Second, forbearance should focus on avoiding perverse incentives and price distortions rather than creating them. Given increased reliance on central bank balance sheet expansion as a tool of monetary stimulus and the poor track record of risk-based capital forbearance, this likely means focusing on risk-agnostic capital constraints.

We are already seeing a new chapter for analyzing public institutions’ role in intervening in the economy. Inflation, plausibly related to fiscal action, poses serious concerns. In some ways, high inflation only sharpens the case for seriously considering monetary action and expansionary banking policy. The fundamental institutional question is evergreen: What is the law’s role in macroeconomic management? In this sense, Tooze and Listokin’s books have lost none of their relevance.

The essay is available here.

Print

Print