Elaine Buckberg is Senior Vice President at NERA Economic Consulting. This post is based on a NERA publication by Dr. David Tabak, available here.

One of the key stages in many securities class actions is class certification. The most common path for plaintiffs to obtain certification includes showing that the market in which the securities at issue traded was efficient, leading to what, in 1988, the Supreme Court in Basic v. Levinson termed a “rebuttable presumption” of reliance common to all class members.

The following year, the court in Cammer v. Bloom listed five factors that would help establish that a security traded in an efficient market. Since then, dozens of courts have relied on these “Cammer factors” in evaluating market efficiency. The rulings do not state, however, how the court reached an overall opinion on market efficiency when different factors point in different directions. To help shed light on this issue, we have examined identifiable cases from 2002 through 2011 in which a court ruled on market efficiency after reviewing some or all of the Cammer factors.

Our review of the data yields a perhaps remarkable conclusion: in over 98 percent of the cases, the ultimate ruling on efficiency can be predicted by the number of factors that the court found favored efficiency less the number of factors that the court said argued against efficiency. When this figure was positive, the court found the security at issue to have traded in an efficient market in all but one instance, while when the figure was zero, the court always found the security to have traded in an inefficient market. Moreover, just limiting the analysis to a review of three Cammer factors (turnover, analysts, and market makers) yields similar results.

Data Collection and Coding Methodology

A list of potential cases for review was obtained from two searches of Westlaw on decisions from 2002 through 2011 using “Cammer” and “market efficiency” as keywords. The search results were then reviewed to determine if they included a ruling on market efficiency through the use of the Cammer and potentially other factors. Cases that relied solely on factors outside of Cammer were not included in the analysis, though the reasoning was still included in the resulting database of judicial statements about the factors related to market efficiency (e.g., a stock that traded on the New York Stock Exchange was deemed in one case to be efficient with an explicit notation that due to its trading market there was no need to undertake a Cammer analysis). Other opinions were excluded when they did not provide an overall review of efficiency factors (e.g., an appellate decision that analyzed only one factor and affirmed the district court’s ruling on that factor or an opinion that ruled that shares issued in an IPO were automatically considered not to have traded in an efficient market).

The five Cammer factors are: “(1) the stock’s average weekly trading volume; (2) the number of securities analysts that followed and reported on the stock; (3) the presence of market makers and arbitrageurs; (4) the company’s eligibility to file a Form S-3 Registration Statement; and (5) a cause-and-effect relationship, over time, between unexpected corporate events or financial releases and an immediate response in stock price.” [1] Courts have supplemented the five Cammer factors with other measures such as market capitalization, bid/ask spread, float, and analyses of autocorrelation. Making the courts’ job more difficult, there are no bright lines for many of the factors, so that, for example, the presence of nine analysts covering a security could lead a court to a finding that that factor was in favor, against, or neutral with regard to market efficiency.

Each of the cases that were downloaded was reviewed by at least three different people to determine the court’s view with regard to each of the Cammer factors and any additional factors such as those listed above. The reason for the multiple review was that sometimes the court’s opinion on a particular factor was not clear, with the decision not always explicitly stating that a factor weighed either in favor or against market efficiency, and, a small number of findings (with never more than one finding per security) were ultimately coded without agreement across the senior reviewers. For each of the Cammer factors, the decision was coded as one in which the court found the factor to weigh in favor of efficiency, the court found the factor to weigh against efficiency, or the court either found the factor to be neutral in terms of efficiency, did not consider it, or did not provide a statement as to which way that factor would enter into an analysis of market efficiency. [2]

Cases were also coded based on whether the court’s ultimate ruling was that a security traded in an efficient or an inefficient market. Complicating this coding were instances of cases covering multiple securities. At one extreme, if the securities were considered separately, they were treated as separate entries, while if the securities were analyzed as a group, they were considered one entry. If multiple securities were analyzed simultaneously but the court reached different conclusions for different securities, then they were treated as multiple entries. The degree to which securities were analyzed as a group can sometimes be a bit uncertain, allowing for alternative interpretations in a limited number of cases.

The different ways that courts approached their discussion of the factors also led to some subjectivity in coding. Still, most of the classifications were clear, though there was an interesting divergence with how courts treated the presence of large institutional shareholders, with some explicitly treating that as a consideration under “market makers and arbitrageurs,” some appearing to treat institutions as a separate factor, and some courts not being explicit in how they coded that factor. [3]

Results and Discussion

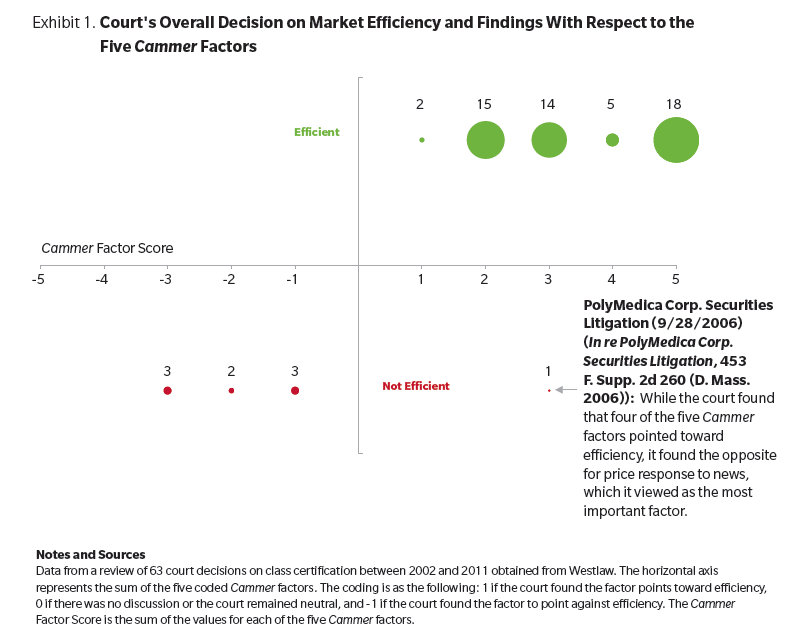

One way to examine the results of the data collection and analysis is in Exhibit 1. In this exhibit, we count the number of Cammer factors in a case that a court said supported efficiency and subtract from that the number of Cammer factors that the court said argued against market efficiency, which we define as a “Cammer Factor Score” for purposes of exposition. Thus, if a court found three factors in favor of efficiency, one factor against efficiency, and one factor to be neutral, a Cammer Factor Score of +2 would be assigned to this case. The Cammer Factor Score is shown in the horizontal axis of Exhibit 1. For each Cammer Factor Score, we also plot a green point representing the number of cases in which the ultimate decision was one of market efficiency and a red circle representing the number of cases in which the ultimate decision was one of market inefficiency; the size of each circle is proportional to the number of cases with the corresponding number of factors and ultimate ruling on market efficiency.

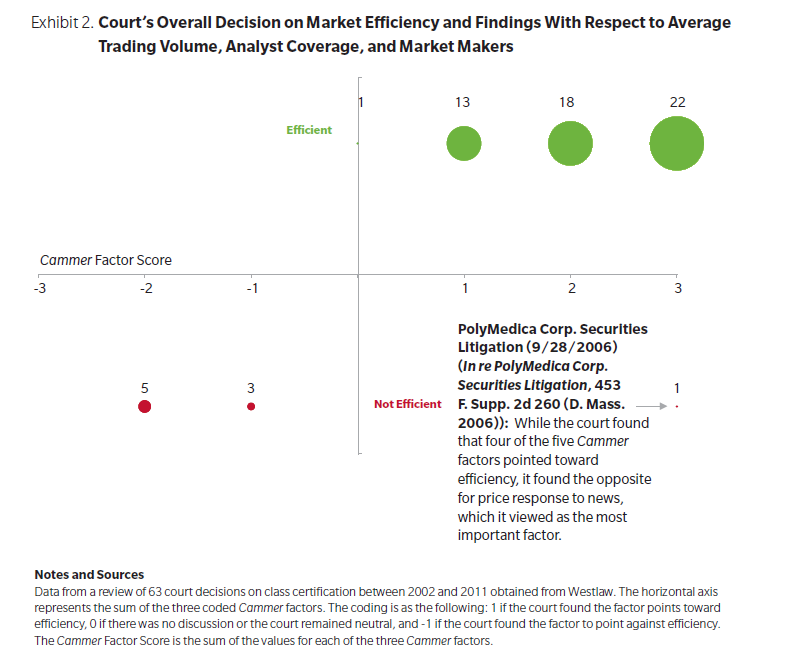

As can be seen in Exhibit 1, the data can be almost perfectly described by a simple rule: if the Cammer Factor Score is positive, then the court ruled that the security traded in an efficient market while if the Cammer Factor Score is negative, then the court ruled that the security traded in an inefficient market. A similar analysis can be done by creating a 3-Factor Cammer Score, applying the same rule but only to the turnover, analyst, and market maker/arbitrageur factors. Results for this analysis are shown in Exhibit 2. One outlier case, PolyMedica, involved a highly disputed situation that dealt with a portion of the class period and involved an appeal up to the Circuit Court level. [4] Part of the reason for the unusual outcome may be because defendants focused on a portion of the class period in that matter in which they could make more targeted arguments.

It should be noted that the analyses in this paper do not explain why the result we find holds. The results are of course logical, because the more factors that favor (in)efficiency, the more likely it is, with no other information, that a security trades in an (in)efficient market so that a holistic review of the evidence yields the same result as a counting of factors. Alternatively, courts could be either consciously or unconsciously performing this type of calculation (i.e., weighing each factor approximately the same) in reaching their ultimate conclusion about market efficiency. Finally, there are claims in the academic literature on other areas of law that courts might reach an ultimate ruling and write up their findings on individual factors in a manner that tends to be consistent with the overall ruling (known as “stampeding” the factor outcomes). [5] Notably, there were no instances in which a court expressly based its ultimate ruling on a count of the number of factors favoring or opposing market efficiency; in fact, some explicitly noted the opposite, echoing or citing the admonition in Unger v. Amedisys Inc. that “once a court endeavors to apply these factors, they must be weighed analytically, not merely counted, as each of them represents a distinct facet of market efficiency.” [6] Whatever courts actually do, the results certainly appear very similar to an exercise in counting.

The findings are also reasonably robust to small changes in our coding if we allow for cases with a Cammer Factor Score of zero to correspond to an overall ruling of either efficiency or inefficiency. Because there are no cases with a five-factor Cammer Factor Score of zero, then there is no case whose compliance with the rule would be affected by changing the way a single factor is coded by one degree (e.g., in favor to neutral or neutral to against). If we allowed for two degrees of change (e.g., changing in favor to against, or making two one-degree changes to different factors) per case, then at most 5 of the 63 cases could be moved from compliance to non-compliance, a situation that would still result in 57 of the 63 cases following the rule.

Conclusion

When facing a multi-factor test, courts often note that they weigh the factors holistically and do not merely count factors. Yet, in an analysis of decisions of market efficiency, courts’ ultimate conclusions often look the same as if they had counted the Cammer factors. There are a number of reasons that this may be true, ranging from factors being correlated (meaning that efficient stocks tend to have clearly positive Cammer Factor Scores while inefficient stocks tend to have negative scores) to courts consciously or unconsciously being influenced by the lack of bright lines for many of the Cammer factors, and thus tending to write opinions that appear to provide a strong basis for the ultimate decision reached.

Endnotes

[1] In re Xcelera.com Securities Litigation 430 F.3d 503 (1st Cir.2005).

(go back)

[2] The way that courts approached this was not always consistent. For example, one court found that the presence of a single analyst satisfied the analyst factor while another found that the presence of two analysts did not provide strong evidence in favor of efficiency but also did not mean that the stock had to be considered inefficient without reviewing the other Cammer factors. Our data collection has also provided us with a database of statements related to the application of the Cammer and other factors that allows for such comparisons.

(go back)

[3] For our analysis, we generally coded institutional holdings as a part of the “market makers and arbitrageurs” factor if the court seemed to be treating those factors together. Alternative treatments would not have a material effect on the results.

(go back)

[4] For purposes of full disclosure, NERA worked for defendants in this matter.

(go back)

[5] At least in the case of market efficiency, what might appear to be stampeding could also be a logical result of interplay among factors. For example, larger companies may be more likely to qualify for an S-3 registration and draw higher-quality analysts. Thus, even if the number of analysts were the same for two companies, it could be reasonable for a court to be more likely to find that that factor supports efficiency for the larger company if, in fact, it was covered by more top analysts.

(go back)

[6] Unger v. Amedisys Inc., 401 F. 3d 316 (5th Cir. 2005).

(go back)

Print

Print