Matteo Tonello is managing director of corporate leadership at the Conference Board. This post is based on an issue of the Conference Board’s Director Notes series by Tim Leech, managing director of global services at Risk Oversight Inc. This Director Note is based on an article written by Mr. Leech; the full publication, including footnotes, is available here.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, companies and their boards have been grappling with new disclosure requirements related to board risk oversight in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Unfortunately, many organizations that have wanted to improve their risk management capabilities have attempted to implement a traditional form of what is generally known as enterprise risk management (“ERM”). Many companies that have tried the traditional ERM route have been disappointed with the results. Many of these ERM programs have focused on multiple workshops that ask participants to identify potentially negative events, assess their likelihood and consequence, log risks identified in “risk registers,” plot them on color-coded risk “heat maps” and report the top 10, 20 or 100 risks to the board. In most ERM programs, this exercise is repeated each year and the updated risk register results are reported to the board or a committee of the board. This approach to ERM has proven to be suboptimal at best, and has even proved “fatal” when companies completely missed entity-threatening risks. These poor results can be related to the fact that these initiatives miss the fundamental point of formalized risk management—increasing certainty that objectives, both strategic and value creating, as well as core foundation objectives like obeying laws and producing reliable financial statements, will be achieved with a tolerable level of risk to senior management and the board.

While ERM programs purport to focus on identifying, measuring, and reporting the company’s top risks, internal audit departments continue to use traditional assessment approaches—developing and completing “risk-based” audit plans and reporting subjective opinions on “control effectiveness”—that apply to what is invariably a very small percentage of the total risk universe each year to boards of directors. Few internal audit departments today use generally accepted risk assessment methods on their audits, evaluate the full range of “risk treatments,” including contractual risk sharing, insurance, and risk avoidance, or provide boards with much information on which objectives have the highest and most dangerous levels of retained risk.

Adding to the confusion is the requirement in Section 404 of Sarbanes-Oxley that orders companies to use “control criteria-centric” assessment methods developed in the late 1970s. The focus of these approaches is on documenting processes, identifying and testing “key controls,” and forming subjective opinions on whether controls are “effective,” not rigorously identifying and analyzing the most statistically probable real and potential situations that cause materially wrong financial statements and identifying and reporting the financial statement line items with the highest retained risk levels. Although both the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) and the SEC are vigorously promoting the need and benefits of ERM, neither has recognized that a properly designed ERM program should be able to evaluate all types of objectives, including producing reliable financial statements, and the full range of risks that threaten the achievement of those objectives.

Boards are asked by the SEC to accept that ERM programs are important elements of an organization’s overall assurance strategy and critical to the identification, measurement, and management of major risks. Unfortunately, these are apparently not the type of significant risks that threaten the objective of reliable financial disclosures. In the author’s experience working with hundreds of companies around the world, few boards in the world today receive reports on line items in financial statements and related notes to the financial statements that have the highest composite uncertainty/retained risk and few SOX 404 programs use ISO 31000 risk assessment methods. To date the SEC has refused to designate ISO 31000, the world’s global risk management standard, as a “suitable” assessment framework in spite of multiple requests.

Guiding principles for improving board oversight of risk can be found in the October 2009 National Association of Corporate Directors (“NACD”) Blue Ribbon Commission report, “Risk Governance: Balancing Risk and Rewards.” The 42-page report distills the key elements of board risk oversight down to six concise goals:

While risk oversight objectives may vary from company to company, every board should be certain that:

- 1. the risk appetite implicit in the company’s business model, strategy, and execution is appropriate

- 2. the expected risks are commensurate with the expected rewards

- 3. management has implemented a system to manage, monitor, and mitigate risk, and that system is appropriate given the company’s business model and strategy

- 4. the risk management system informs the board of the major risks facing the company

- 5. an appropriate culture of risk-awareness exists throughout the organization

- 6. there is recognition that management of risk is essential to the successful execution of the company’s strategy

Although the NACD report does not call for integration of ERM efforts, internal audit methods, and SOX 404 methodologies, these are precisely the goals a high-performing board should strive to achieve with respect to risk oversight related to all types of business objectives, including creating shareholder value, producing reliable financial statements, and complying with laws like the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Unfortunately, real world experience has shown that many companies are ill–equipped, or in some cases, unable or reluctant to integrate their assurance approaches and provide boards with the information needed to meet those goals. To date, neither the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) nor the SEC has shown much willingness to help them with this task. In spite of formal written requests, and papers and presentations from the Institute of Management Accountants in the United States, the SEC has refused to allow internationally accepted risk management assessment frameworks to be used for SOX 404 efforts. Although the majority of IIA training still promotes traditional direct report audit methods focused on auditors determining their view of what constitutes “effective control,” the IIA has recently adopted new standards and launched a new certification in risk management assurance (CRMA) designation, signaling that they may be willing to try and transition the profession away from providing subjective opinions on control effectiveness and focus on ensuring senior management and the board are aware of the most significant retained risk areas.

Other Drivers Elevating Board Risk Oversight Expectations

In addition to the recommendations in the NACD Blue Ribbon report, other important developments are escalating board risk oversight due diligence expectations globally.

Security regulators want more disclosure The Securities and Exchange Commission requires companies to publicly disclose specific details about how their boards are discharging their risk oversight responsibilities in their annual proxy statement. In Canada, companies must disclose that their boards are formally responsible for risk oversight, and detail in their Annual Information Form (AIF) how their boards are meeting risk oversight expectations.

Credit rating agencies are starting to score risk oversight Major credit rating agencies now include questions about board risk oversight in their credit rating review process. If a rating agency is considering downgrading a company’s credit rating, the assessment of corporate governance and board risk oversight practices could help avoid a costly downgrade that ratchets up a company’s cost of capital.

Institutional investors are interested Investor organizations, such as the International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN), which represents managed assets totaling more than $18 trillion, recommends that its members include an evaluation of corporate governance and board risk oversight in their due diligence process when making investment decisions. The results of these reviews can materially impact a company’s share price.

Internal auditors must report on risk management processes The IIA introduced new professional practice standards in 2010 that explicitly require internal auditors to assess and report their opinion on the effectiveness of their company’s risk management processes to the board of directors. New IIA standards that take effect in January of 2013 require that chief audit executives report any areas they believe are outside of the organization’s risk appetite to the board. As previously noted, the IIA also launched a new professional CRMA certification in 2012 to equip its members to meet the new reporting requirements. More than 8,000 professionals have qualified for this new designation as of December 2012.

Authoritative risk oversight guidance is impacting director “duty of care” expectations In addition to the NACD guidance, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) issued specific risk oversight guidance for directors in June of 2012. In the United States, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) has issued a number of surveys and guidance on board risk oversight practices. The increase in authoritative guidance on board risk oversight is influencing judicial views about what constitutes a reasonable director “duty of care.” As the board risk oversight standards rise, it is likely that U.S. courts will slowly adjust their view of what a “prudent” director needs to do to demonstrate they are meeting society’s view of reasonable care. A Harvard Law School Forum blog post titled, “Risk Management and the Board of Directors – An Update for 2012,” provides an excellent overview of current legal expectations.

Tips for Achieving NACD Risk Oversight Expectations

The following section provides recommendations for boards for achieving the six risk oversight goals espoused by the NACD Blue Ribbon Commission report.

GOAL: THE RISK APPETITE IMPLICIT IN THE COMPANY’S BUSINESS MODEL, STRATEGY, AND EXECUTION IS APPROPRIATE

In order to achieve this goal, directors must first understand what is meant by the terms “risk appetite” and “risk tolerance.” Two good places to start are the COSO’s January 2012 discussion paper, “Enterprise Risk Management: Understanding and Communicating Risk Appetite,” and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Guide 73: Risk Management – Vocabulary. For ISO definitions of risk appetite and risk tolerance, see the box below.

ISO Definitions

Risk appetite

The amount and type of risk that an organization is willing to pursue or retain.

Risk tolerance

An organization’s or its stakeholder’s readiness to bear the risk after risk treatment in order to achieve its objectives.

Source: ISO Guide 73: Risk Management – Vocabulary, 2009

Next, directors must ask the question, “how are we (the board of directors) going to oversee management’s risk appetite and tolerance across the enterprise with limited time and resources?”

The simplest approach is to ask the company’s CEO and CFO how they plan to ensure that the board meets the NACD risk oversight expectations. This request should kick-start an assessment of the company’s current policies, processes, practices, and capabilities. Because of legal concerns related to discoverability of risk assessment materials, particularly in the United States, some boards may not want to know more about management’s risk appetite/ tolerance because of the potential impact on personal and corporate legal risk. A gap assessment using NACD risk oversight expectations can be conducted by an objective outside risk oversight expert, or internally by the company’s internal audit function if one exists and is capable. If possible, this should be done via the legal department to provide legal privilege over the findings of the gap assessment.

The board can also ask management during the company’s annual planning cycle to identify the critical strategic objectives and targets with the highest composite uncertainty of achievement, including the specific risks and related likelihood and consequence estimates that threaten the achievement of those objectives and performance targets. This should be accompanied by candid discussion and an analysis of the organization’s ability to manage or, to use risk speak, “treat” the risks identified, particularly if things go seriously wrong.

In addition, the board should schedule time to discuss the organization’s “risk appetite” and “risk tolerance,” including risk acceptance decisions that could result in working capital erosion (i.e., the 2008 financial crisis ) and the negative consequences that may arise from regulatory infractions (e.g., Foreign Corrupt Practices Act violations/ prosecution, stock option backdating, environmental violations, etc.), financial statement restatements, safety and environment incidents, overly aggressive tax planning/ execution strategies, and other major value eroding events.

GOAL: THE EXPECTED RISKS ARE COMMENSURATE WITH THE EXPECTED REWARDS

Management generally does a good job describing expected rewards in terms of increased profits, market share expected, reduced costs, lower legal liability, etc. Unfortunately, many organizations lack rigorous processes to identify “expected risks” linked to strategic plans. At a minimum, boards should ask to see documented risk assessments of the organization’s key strategic business objectives and the less exciting “foundation objectives,” such as reducing fatalities/lost time, compliance with laws, reliable financial disclosures and others. Management should specifically provide reports to the board on risk related to laws that affect the company that are currently on, or just about to be put on, enforcement agencies’ top priority enforcement lists, like major environmental incidents, the FCPA, and anti-money laundering for banks. Risk identification and assessment needs to include “expected risks,” as well as “plausible risks.” For example, the risk that the U.S. real estate market was due for a major correction leading up to 2008 was very plausible based on an analysis of 100 years of U.S. real estate values. Unfortunately, the majority of companies with massive exposure to this risk didn’t take the time to obtain and consider this data when evaluating the risks linked to collateral backed securities.

GOAL: MANAGEMENT HAS IMPLEMENTED A SYSTEM TO MANAGE, MONITOR, AND MITIGATE RISK, AND THAT SYSTEM IS APPROPRIATE GIVEN THE COMPANY’S BUSINESS MODEL AND STRATEGY

If they haven’t already, boards should gain a solid understanding of the varying levels of enterprise-level risk management processes sophistication. The goal is to match the level of risk management process sophistication and maturity to the environment the organization operates in and management’s strategies that are in place or planned that expose the organization to high risk. High levels of risk management sophistication are expensive and often unnecessary. Organizations in relatively simple, stable industries, such as household goods, retailing or domestic raw materials, don’t need the same level of risk management processes as nuclear energy producers, companies operating in countries prone to bribery, or companies using and/or offering very complex financial instruments. The more dynamic and complex the company’s risks, the more sophisticated its risk management processes should be. One tool the board can use to evaluate the level of sophistication required for the company’s risk management processes is the “Risk Fitness Quiz” shown below.

Boards of public companies that have an internal audit function should demand that the chief audit executive (CAE) provide his or her opinion on the effectiveness of the company’s risk management processes if they haven’t done so already. The IIA International Professional Practices Framework Standard 2120 now states this is a “must do” component of the internal audit professional practice standards. Unfortunately, a survey conducted by the IIA Audit Executive Center in the first half of 2012 indicates that the majority of internal audit functions have not complied with this requirement. Reasons cited by CAEs include “The board hasn’t asked for that information,” “I don’t know how,” and “management doesn’t want me to report my observations on how the company manages risks to the board.” The IIA is attempting to address this issue by dramatically elevating the importance of this requirement globally. In a September 2012 blog post exhorting IIA members to comply with the standard, IIA global president and CEO Richard Chambers asks, “What are we waiting for?” It is likely that many chief audit executives are waiting for the CEO, CFO, and/or the board to ask them for their opinion.

GOAL: THE RISK MANAGEMENT SYSTEM INFORMS THE BOARD OF THE MAJOR RISKS FACING THE COMPANY

As a result of the evolution of the internal auditing profession’s standards, training, and generally used internal audit practices; and regulatory interventions like Sarbanes-Oxley in the U.S., many companies and internal auditors report subjective opinions on “control effectiveness” on a small percentage of the risk universe each year to boards of directors and, in the case of financial disclosures, publicly to outside stakeholders against criteria contained in the largely obsolete 1992 COSO Internal Control Integrated Framework. Unfortunately, this approach provides boards with little specific information on major risks to financial statement reliability and, most importantly, on residual/ retained risk positions. COSO has confirmed that it will not integrate its enterprise risk management framework with the five 1992 control categories in the forthcoming update scheduled for release in 2013. It is likely going forward that U.S. companies will still be obligated by the SEC in the United States, and by the Canadian Security Administrators/Ontario Securities Commission in Canada to report binary opinions on “control effectiveness” against the seriously flawed COSO Internal Control Integrated Framework, a framework that has regularly proven to be unreliable. A proposal submitted to the SEC in the form of a paper published in the International Journal of Disclosure and Governance calling for amendments to SOX Section 404 to shift from the current “control criteria-centric” approach to one that focuses on statistically plausible risks to reliable financial disclosures was rejected. This can be best termed “regulator-imposed risk” on a global level.

In the area of external financial disclosures, few organizations report composite residual risk ratings (the composite uncertainty that the disclosure is reliable) to boards on line items and notes in financial statements (i.e., the line items with the highest possibility of being materially wrong). They also don’t report on risk status linked to critical strategic objectives, including objectives linked to revenue, market share, and cash generation; minimization of unnecessary costs; product quality; customer service; safety; fraud prevention; and other important dimensions necessary for sustained success. Boards are often told there are hundreds, or even thousands of “control deficiencies” from spot-in-time audits conducted during the year, and given lists of just the “Top 10” or “Top 20 Risks” drawn from “Risk Registers,” rather than reports on the key business objectives that have the highest composite residual/retained risk positions.

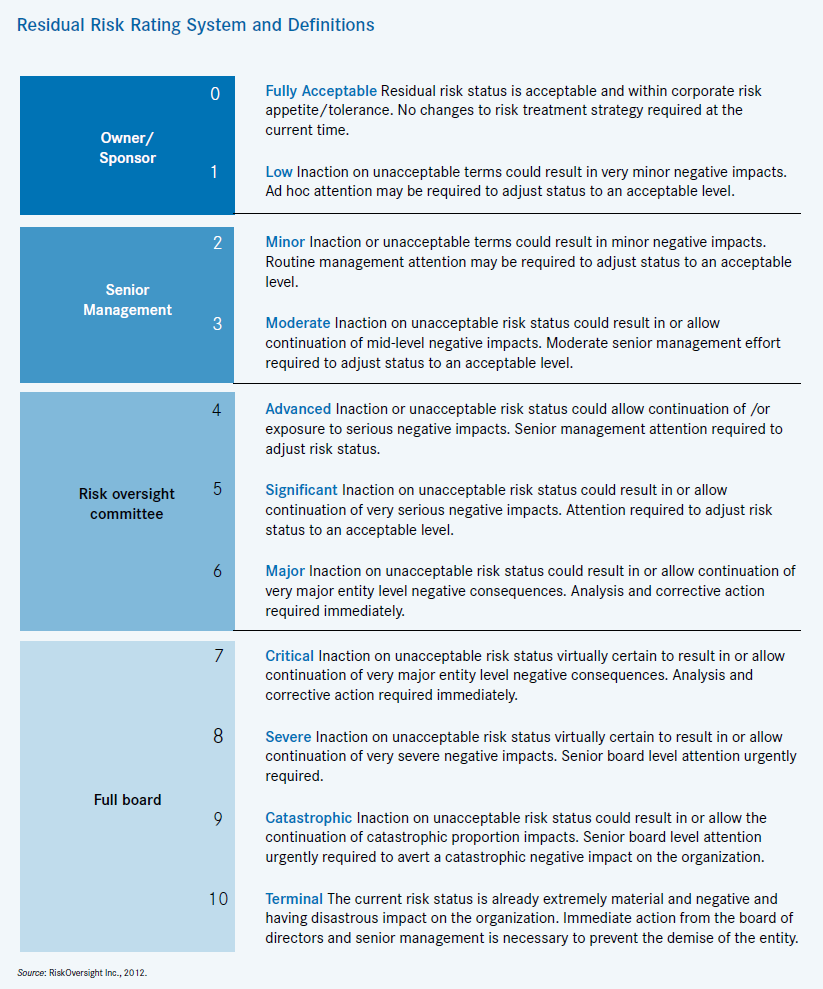

Boards should demand regular reports on the current “residual risk status” of strategic and core business objectives. One approach is to implement a “business objective register”—a repository of important business objectives senior management and/or the board want assurance on, including value creation objectives, reliable financial statements, and others—by assigning specific “owners/ sponsors” for the objectives; and requiring that the board be provided regular reports on the end-result business objectives that have high composite residual risk ratings. A simple residual risk rating system is shown below.

This approach would provide senior management and the board of directors with easy to understand composite uncertainty ratings, including the potential impact on the organization on the full range of objectives necessary for long-term success. Using this approach, internal audit’s primary job is to provide opinions to the board on the reliability of the consolidated report on residual risk status. Currently, boards of directors are expected to take comfort in binary opinions on control effectiveness from CEOs, CFOs, the company’s external auditors; and internal audit reports on a fraction of the risk universe that identify “control deficiencies,” “material weaknesses,” and other methods that mask candid disclosure of retained risk positions. Unfortunately, these subjective opinions on control effectiveness reported to boards are frequently proven wrong by subsequent events.

GOAL: AN APPROPRIATE CULTURE OF RISK-AWARENESS EXISTS THROUGHOUT THE ORGANIZATION

The risk awareness culture must start at the board level and extend all the way down to the shop floor. In most cases, this goal cannot be met without implementing some form of ERM or “integrated risk management” (IRM). This requires that an organization adopt common terminology to discuss and report on residual risk status; define specific accountabilities; provide adequate training on structured risk assessment methods, and adopt appropriate risk assessment and reporting tools and technology. One dimension that has been consistently underestimated by ERM sponsors is the need to include formal skills development, including defining risk oversight learning objectives for boards, senior management, work units, internal audit, safety, insurance and other assurance groups related to the core elements of risk management.

GOAL: THERE IS RECOGNITION THAT MANAGEMENT OF RISK IS ESSENTIAL TO THE SUCCESSFUL EXECUTION OF THE COMPANY’S STRATEGY

Thanks to their real-world business experience, the vast majority of board members recognize that managing risks well is a key element of sustained business success. What many boards grapple with is the need to transition from managing risk with limited formal and visible processes and structure—an approach that may not be adequate given the complexity and speed of change in today’s world. Boards must acknowledge that increased risk management rigor and structure are increasingly expected by regulators, credit rating agencies, institutional investors, customers, and the courts.

Meeting these six NACD risk oversight expectations requires a strong commitment from the boards and management. Without that commitment, the chances of another global financial crisis and colossal governance failures like those seen at Enron, WorldCom, MF Global, the BP Gulf of Mexico environmental disaster and others remains a very real and probable risk. Boards must reconsider the traditional risk and assurance approaches used by most companies and demand better information to help them achieve their oversight goals.

Print

Print