Marco Ventoruzzo is a comparative business law scholar with a joint appointment with the Pennsylvania State University, Dickinson School of Law, and Bocconi University; Piergaetano Marchetti is Professor of Commercial Law at Bocconi University. This post comes to us from Professors Ventoruzzo and Marchetti.

Italian law provides for a fairly unique and interesting mechanism allowing “minority” shareholders to appoint a percentage of board members. In a nutshell, this system—called “list voting” or “slate voting” and regulated by the “Consolidated Law on Financial Markets”—injects an element of proportionality in the election of the board. It is profoundly different from “proxy access” in the U.S., but it shares with it the underlying goal of granting a stronger voice to institutional investors and qualified minorities. Significant differences also exist with “cumulative voting,” a rule more familiar to American readers, because list voting is more simple and leads to more predictable outcomes. As the discussion on proxy access and active investors unfolds in the U.S. and other countries, and also considering the significant investments of international funds in Italian listed corporations, it is interesting to take a closer look at these rules and their actual impact.

From an historical perspective, list voting was first introduced in 1998 but limited to the board of statutory auditors, the controlling body provided by the traditional Italian corporate governance model, appointed by the shareholders’ meeting and separate from the board of directors. In 2005, also as a reaction to corporate scandals, the legislature extended this rule also to the appointment of directors, therefore involving minority shareholders more directly in the management of the corporation.

In brief, all shareholders of listed corporations reaching a minimum threshold of shares, calculated based on the capitalization of the issuer (often around 1.5%), can present a “list” for the election of the board. A statutory provision mandates that all directors will be picked from the list receiving the greatest number of votes, but a minimum number (generally one, but bylaws can increase this number) of directors will be taken from the list receiving the second highest number of votes, provided that it has no connections with the first list. In light of the concentrated ownership structures prevailing in Italy, the system can be considered an important check on the power of controlling shareholders, and “minority lists” are generally prepared and voted by institutional investors.

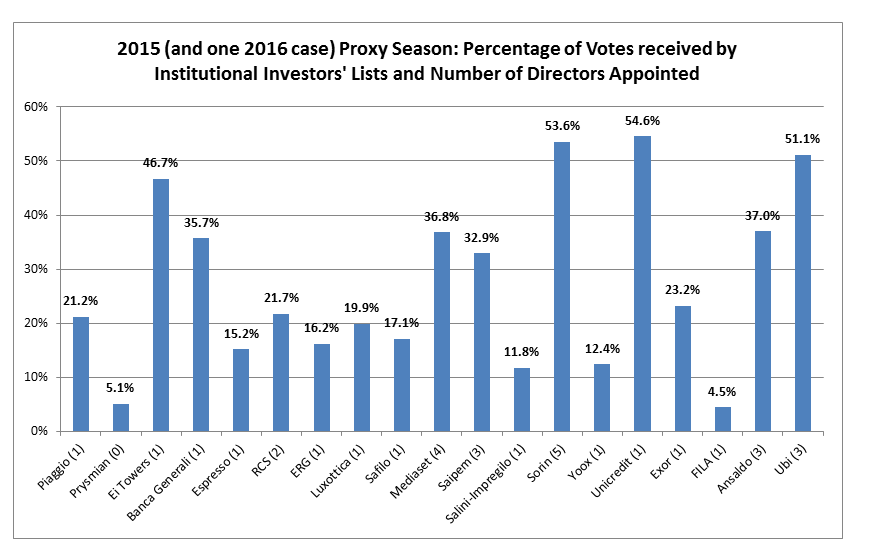

The system works smoothly when, for example, the list of the “controlling” shareholder receives 45% of the votes, and the second, independent list obtains 16%. The list presented by institutional investors, in larger corporations, often receives significant support at the annual shareholders’ meeting, also capturing the votes of dispersed minorities. In some recent cases, however, it has received more votes than the ones cast for the candidates suggested by the allegedly “strong” shareholders, and occasionally even an absolute majority of the votes. Notwithstanding this, the list of institutional investors generally only appoints a small fraction of directors. The following graph illustrates this situation with respect to the last “proxy season”: the percentage of votes received is indicated in the bars, and the number of directors actually appointed is in parenthesis next to the name of the corporation (elaborations on data from Assogestioni and Consob):

Note the situations in which a list has received more than 30% (and, in four cases, around or more than 50%) of the votes cast, but has nominated and therefore elected only a minority of board members, while the majority of the board has been picked, in fact, from the list receiving the second highest number of votes. There are different reasons for this. Primarily and somehow simplifying, even when institutional investors might obtain the majority of the votes, they do not want—or, according to some interpretations, they cannot due to regulatory limitations—appoint a majority of the board members. The job of institutional investors is not to manage a corporation and control its board, and while they are eager to have a voice on the board, they refuse to—or cannot—play a different and more relevant role. This is perfectly in compliance with the law, but in some situations the outcome is paradoxical: the majority of the shareholders appoints a minority of directors, and the minority appoints a majority!

This result raises important questions on the role of institutional investors, recently evoked also by the Chairman of Consob, the Italian Stock Exchange Commission, in his annual report on the activity of the Commission.

The first one is whether the limits to the directors appointed by institutional investors, either mandated by regulation, set forth by bylaws, or self-imposed are entirely desirable. Is it right, for example, that a list receiving over a third of the votes cast only appoints one or two directors in a board composed of twelve members?

Second: once elected, directors are in principle fiduciaries of the corporation and all shareholders. They do not, and cannot, have a specific fiduciary duty toward the group of shareholders that have nominated or voted them. This is, however, the theory. In practice it is clear that these directors feel, so to speak, a stronger “proximity” with the investors that have supported them and the interests they represent. This phenomenon of course happens whenever there are different groups of shareholders, and is not inherently problematic. The interesting twist of the Italian experience, however, is that this situation is genetically engineered into the system, and leads to delicate issues, for example, concerning sharing information with selected investors. Of course market abuse rules exist, both at the EU and national level, to ensure fair disclosure and avoid information asymmetries, but the line to walk is sometimes a fine one.

Third, the most extreme cases lead to boards in which a minority of directors are particularly strong in light of the large number of votes received. What is the real influence, within the board, of two “minority” directors appointed, however, by a majority of shareholders, especially when a financial transaction needs to be approved also with the vote of the shareholders?

One final question that must be mentioned is whether, also in light of these voting patterns, it would make sense to allow executives or directors to also present their own list, something currently problematic and not clearly regulated under Italian law. Because of the concentration of ownership structures, this approach might in fact simply result in greater leverage for controlling shareholders, indirectly influencing board members and executives, but this possibility might also make the board more independent from specific shareholders, and deserves further consideration. The board, in fact, might have an incentive to include in its list also candidates appreciated by institutional investors to attract their vote. In this way, institutional investors might be relieved from the “embarrassment” of being majority at the shareholders’ meeting, minority in the board, and the risk of being perceived as the “prompt” in the “theater” of corporate governance, suggesting the lines to the “actors” of the board drama.

Print

Print