Josh Black is Editor-in-Chief at Activist Insight. This post is based on excerpts from The Activist Investing Annual Review 2017, published by Activist Insight in association with Schulte Roth & Zabel, and authored by Mr. Black, Paolo Frediani, Ben Shapiro, and Claire Stovall. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here), The Law and Economics of Blockholder Disclosure by Lucian Bebchuk and Robert J. Jackson Jr. (discussed on the Forum here), and Pre-Disclosure Accumulations by Activist Investors: Evidence and Policy by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Robert J. Jackson Jr., and Wei Jiang.

The juggernaut of shareholder engagement kept rolling in 2016 as a surge of one-off campaigns, governance-related proposals and remuneration crackdowns made for a busy year. 758 companies worldwide received public demands—a 13% increase on 2015’s total of 673—including 104 S&P 500 issuers and eight of the FTSE 100.

Yet for dedicated activist investors, it was a more muted affair. Investors deemed by Activist Insight to have a primary or partial focus on activism targeted fewer and smaller companies, accounting for just 40% of the total which faced public demands, and 10% fewer companies in North America. Turbulent markets, redemptions and competition all played a part in reducing the volume of activist investing. By contrast, shareholder engagement flourished.

With hangovers from poorly timed investments in energy markets, the near-demise of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International and antitrust concerns breaking up deals on which activists had bet substantially, dedicated activists enjoyed a particularly poor start to the year in the U.S. Jason Ader, the CEO of SpringOwl Asset Management, told Activist Insight for this report that 2016 might be “the year that activists were humbled.”

However, the number of newly engaged investors suggests the feeling is not widespread. According to Activist Insight, 51 primary, partial or occasional focus U.S. investors founded since 2009 launched their first U.S. campaign in 2016, up from 38 the year before. Although the data include recently founded activist firms, the universe of activists is expanding rapidly.

Indeed, engagement activists, typically institutions or individuals that push for governance changes, targeted 155 companies worldwide in 2016—up 24% after three years in which activity had remained flat. But it was “occasional” activists—which do not include activism as part of their regular investment strategy but which make infrequent public criticisms of portfolio companies—that account for the highest volume, making demands at 311 companies.

Not all of these demands trouble management equally. Only 58% of resolved demands initiated in 2016 were at least partially successful, with the rate of achievement rising with the focus level of the activist. That rate may yet fall as campaigns are resolved, with 2014 and 2015 both posting around 53% at least partially successful.

Downsizing

One of the most notable trends of the year was the strengthening of small cap activism, at the expense of the large targets activists have increasingly pursued. While the number of targeted companies valued at more than $10 billion rose marginally overall, among primary and partial focus activists it fell from 44 in 2015 to 30 last year. Indeed, in 2016, the sub-$2 billion market cap arena accounted for 78% of all targets, up from 72% in 2015 and 70% in 2014. After mixed results, Ader says he is unlikely to repeat his PR-heavy campaigns at Viacom or Yahoo, where SpringOwl published lengthy presentations in 2016.

That may continue to be a trend this year, unless activist fundraising picks up substantially. Assets under management of primary focus funds globally fell from $194 billion in 2015 to $176 billion—still higher than in 2014, but their first drop in five years.

Despite the tough climate, activists are still raising funds—SpringOwl and long/short specialist Spruce Point launched new ones, while Hudson Executive Capital and Marcato Capital have had some success with prior launches. Co-investment, meanwhile, remains a favored strategy for both new and old activists.

Major activists were undoubtedly preoccupied—Icahn by bearishness, Trian Partners by several new positions taken a year previously, and Pershing Square Capital Management by turning around Valeant, although Ackman’s fund did participate in overhauling the board of Chipotle Mexican Grill late in the year. If all three become more prolific in 2017, large caps could yet face renewed scrutiny.

Towards financials

Activism in the technology sector was proportionately flat for the third straight year, this despite activity that ensured it remained one of the most publicized areas, including Starboard Value’s brief threat of a full board contest at Yahoo before a settlement was reached. M&A continued to provide activists with an exit strategy in the sector, including for Elliott Management targets EMC, Infoblox and Qlik and other companies such as Epiq Systems (Villere & Co) and Outerwall (Engaged Capital).

Moreover, a post-election rally notwithstanding, activists that have made their living focusing on buyouts in the sector—Elliott and Viex Capital among them—are unlikely to suffer a drought, according to Evercore’s Bill Anderson.

Financial stocks have also been facing the heat, with volume up 28% in the U.S. and 15% globally. Proxy contests at FBR & Co and Banc of California stand out, while a rally in such stocks after the November election of Donald Trump to the presidency of the U.S. may portend more M&A among small banks and property and casualty insurers, Anderson added in an interview for the complete publication (available here).

The next frontier

Bullish M&A markets have allowed activists to play “bumpitrage” by seeking higher offers from previously announced deals. After Britain voted to leave the European Union, a host of such mergers were exposed to calls for re-evaluations by disgruntled shareholders, as at SABMiller and Poundland in the U.K. In Europe, Elliott Management took up holdout stakes in XPO Europe and Ansaldo, while Paris-based Charity Investment Asset Management has also specialized in defending minority investors in controlled companies.

Getting a hearing became easier in Europe in 2016, with Rolls-Royce Holdings becoming the first FTSE 100 company to cede a board seat to an activist (ValueAct Capital Partners) and Active Ownership Capital winning a seat at Stada in a rare German proxy contest. Whether similar trends emerge in regions where the culture of shareholder activism remains underdeveloped, such as Asia and Australasia, remains to be seen. Back in the U.S., if securing a hearing becomes more of a challenge again, it will be due to the spread of activism, not the lack of it.

Activism booms outside the US

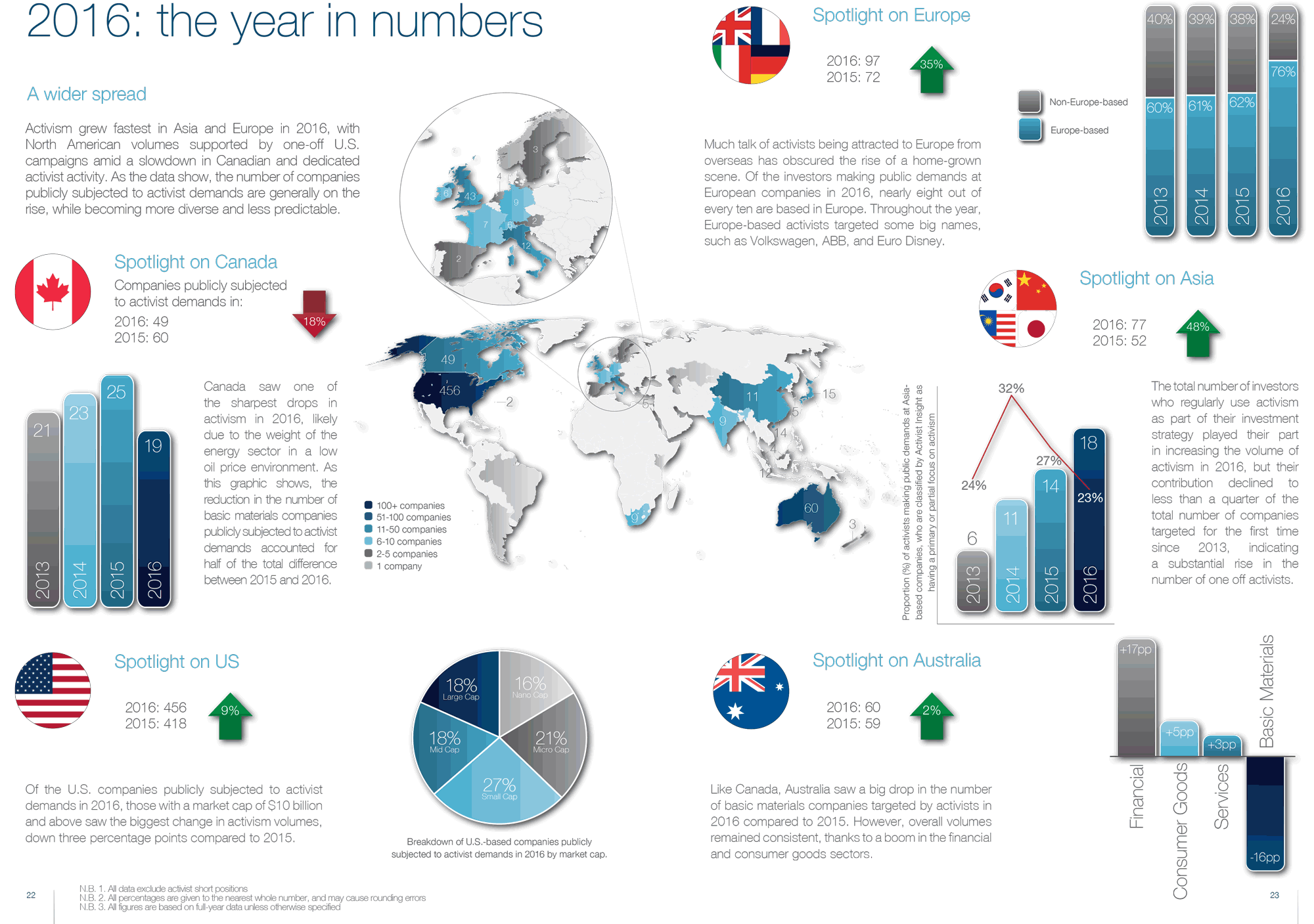

Activism outside the U.S. exceeded expectations in many regions in 2016, with the number of public targets surging despite the preference for privacy in European and Asian countries, where investment communities are averse to public spats, shareholders do not have stringent disclosure requirements for their plans, and most activism takes the form of behind-the-scenes negotiations.

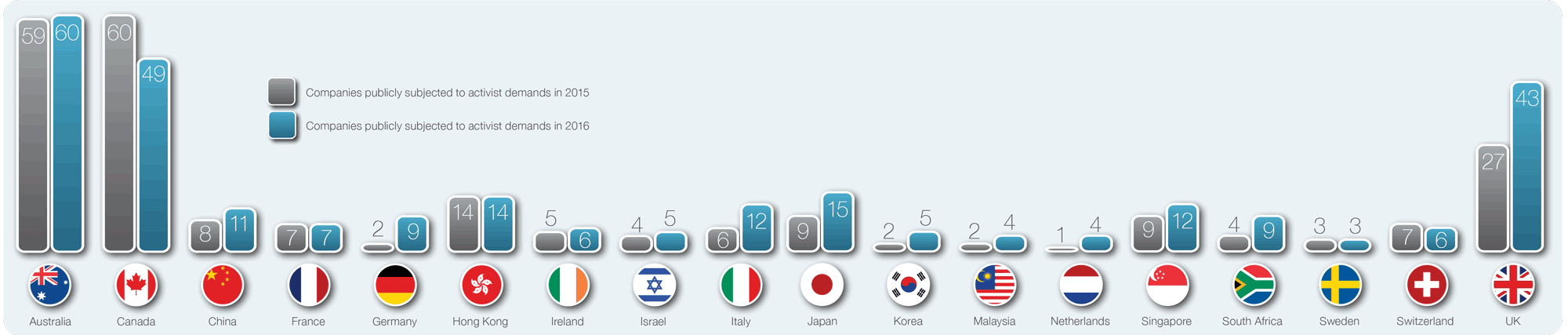

The number of European companies publicly facing activist demands in 2016 reached 97, up from 72 in 2015, and in Asia it rose to 77, up from 52 in 2015. The growth in these regions compensate for stable activity in Australia and a slowdown in Canada. In percentage terms, the number of companies in the crosshairs of activists outside the U.S. reached 40% of the total in 2016, up from 38% in 2015 and 35% in 2014.

Event-driven Europe

The U.K. has always been at the forefront of European activism, and 43 companies publicly targeted in 2016 had their headquarters in the country—up from 27 in 2015.

The outcome of the Brexit referendum in June did not scare activists away. Instead, London-based RWC Partners and U.S. activist Livermore Partners said in interviews with Activist Insight that Brexit made potential targets cheaper. Livermore’s David Neuhauser added that the increased uncertainty will force British companies to seek ways to unlock shareholder value, creating opportunities for activists.

In Germany, where the number of companies targeted rose from a six-year nadir of two in 2015 to nine in 2016, and in Italy, where it rose from six to 12, the surge was partially correlated with the increasing presence of foreign institutional investors in the two countries. In the second half of 2016, governance adviser CamberView Partners boosted its European office, and the firm’s new managing partner for the region, Jean-Nicolas Caprasse, told Activist Insight that Continental Europe has seen an increased presence of institutional investors from the U.S. and the U.K.—ideal interlocutors for activists.

Along with established activists Elliott Management and Amber Capital—both extremely busy in Europe in 2016—Swiss investment firm Teleios Capital Partners disclosed a series of activist positions in the U.K., Active Ownership Capital and The Children’s Investment Fund Management waged historic campaigns in Germany, and British institutional investors such as Standard Life Investments, Royal London Asset Management and Hermes Investment Management were often vocal with their portfolio companies.

The Asian boom

In Japan, the number of companies targeted by activists increased from nine in 2015 to 15 in 2016. The Japanese surge was expected by many, as favoring shareholder activism was part of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s plan to revive the country’s economy. In Singapore, it increased from nine to 12, in China from eight to 11 and in South Korea from two to five—with Elliott Management once again waging a high profile campaign at the Samsung group.

David Hurwitz of SC Fundamental—which operates in South Korea in tandem with local activist Petra Capital Management—told Activist Insight that dissident investors in the country had been helped by increasingly loud calls from market participants, including the government and the State pension fund National Pension Services, for better capital allocation at listed companies—which tend to hold huge piles of cash.

Dektos Investment’s Roland Jude Thng and Quarz Capital Management’s Jan Mörmann, two activists operating in Singapore, said in interviews with Activist Insight that excess cash is often an issue in Singapore too, and that the poor performance of the stock market, the undervaluation of several companies, and cultural changes are making shareholders more demanding.

As for China, most of the companies targeted by activists are listed in the U.S. or Hong Kong, due to a larger mass of institutional investors outside the mainland, according to activist Peter Halesworth, the head of Heng Ren Investments. However, in an interview with Activist Insight he said, “Some of the most energetic and clever activists that we have met are Chinese and living in China. They are very sensitized to their rights, and know a bad deal when they see one.”

In India, a battle between Tata Group’s patriarch Ratan Tata and Cyrus Mistry, the chairman of several of the conglomerate’s portfolio companies, brought U.S.-style governance battles to the attention of the financial press for months.

Australia, and Canada’s slowdown

The global surge in activism in 2016 was not driven by the basic material sector, where the number of companies targeted rose by just one, to 119, from 2015’s total. Difficulties faced by natural resources companies made activists less willing to engage in campaigns in Canada and Australia, where miners and oil and gas firms have traditionally been their favorite targets. In Canada, only 49 companies faced public activist demands in 2016, down from 60 in 2015. In Australia, there were 60 targets, up from 59 a year before, and only 48% in the basic material sector, against 64% in 2015. That said, Australia has almost twice as many targeted companies per inhabitant than the U.S., while Canada does not lag far behind its neighbor.

2016: the year in numbers

Diminishing returns

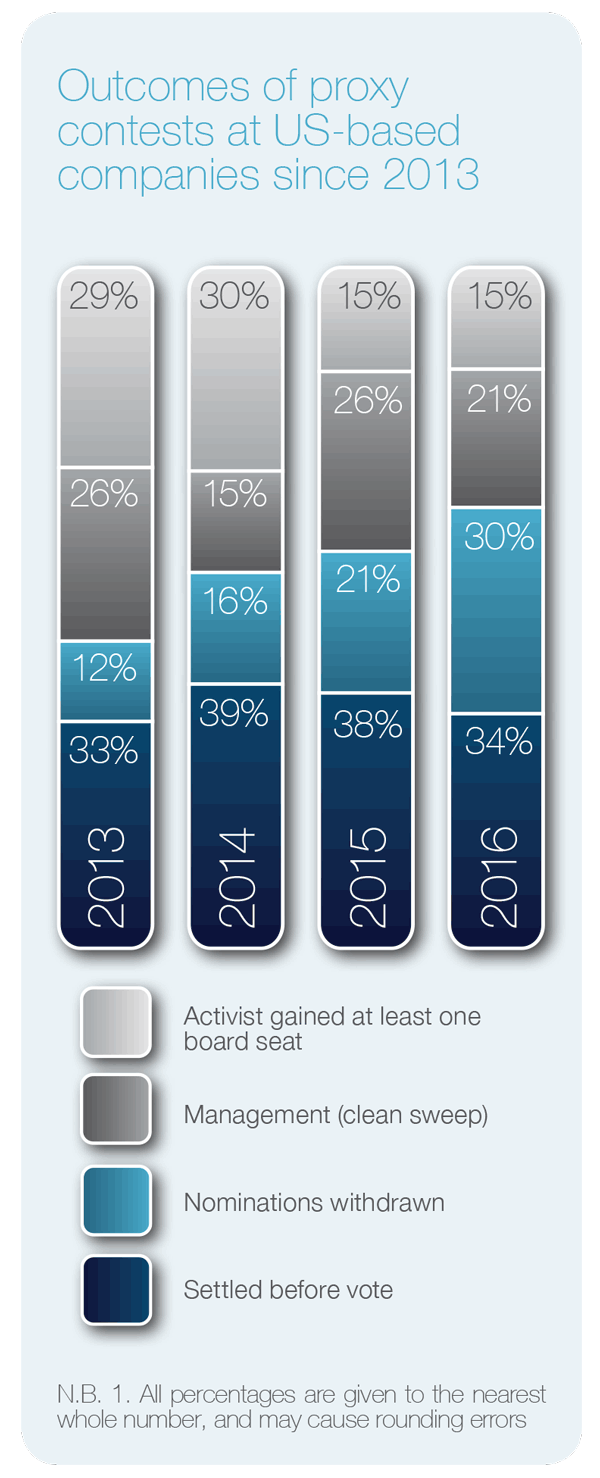

As the number of activist situations has risen over the past half-decade, the prominence of the strategy has enabled both issuers and investors to understand its capabilities and limitations, to the point that the two sides have generally avoided its most costly byproduct, proxy contests.

After two years in which more than half of demands for board seats settled before a contest, 2016 saw 63% settle early. That percentage has been on the rise since 2012, and represented a major jump from 2015, when activists and companies settled without a public spat 54% of the time.

“Management teams and boards are becoming more sophisticated and actually appreciate the value that shareholders that have a long term view can add,” said Chris Teets, partner at Red Mountain Capital Partners. “There is certainly a heightened willingness to settle between shareholders and management teams, and it tends to be the most egregious cases when you tend to see the fights.”

At the 212 U.S. companies where activists sought board seats in 2016, only 65 companies opposed nominations, and of those nearly one-third settled later in the process. Yet, while 2012 and 2013 saw the outcomes of shareholder votes go mostly to the activists, the advantage reversed in 2015 and 2016—last year dissidents won at least one board seat in nine contests, to 13 clear sweeps for management, including one for Roomba maker iRobot over Red Mountain.

While the total number of settlements has risen in recent years, investors are gaining fewer board seats overall. Where at least partially successful, activists gained 1.5 seats per company in 2016, on average, compared to 1.7 the year before and over two in each of 2013 and 2014. The trend may be attributable to a higher frequency of withdrawals, as investors make optimistic demands and then walk away from a fight after a company calls their bluff. Some 30% of contests saw activists withdraw their nominations in 2016, compared to 21% in 2015 and just 12% in 2013.

The combined effect of increased withdrawals and issuers becoming more adept at shutting out investors can be seen in the declining number of board seats gained by activists each year. After activists gained a record 276 board seats in 2014 at just 154 companies, they were only able to accrue 215 director positions in 2016 despite launching 212 campaigns aimed at board representation.

It may only get worse, according to Luma Asset Management Founder Greg Taxin, who is confident the universal ballot, which would force companies to issue a single proxy card containing both its director candidates along with the dissidents’, will be approved in late 2017. The hedge fund manager admitted the rule will not be implemented until next proxy season, but unlike most investment managers, he believes it will be detrimental to activists.

“Under today’s system, investors are put to a hard choice, fully support status quo, or vote on any, or some amount of change,” said Taxin. “Because most companies that go to fight are well chosen by dissidents, investors vote on the dissident card, and in doing so starve management of votes, because they can’t mix and match.”

Taxin went on to say that under the universal ballot, investors will naturally give votes to management in addition to voting for one or two members of the dissident slate. The change would be beneficial to issuers, which would more often avoid comprehensive defeats at the hands of activists.

“I ran three proxy fights for a majority of the board and won all three times. Part of the reason I won is because they wanted some amount of change and voted on my card, and management got no votes,” said Taxin said Taxin, who serves as an adviser on a number of activist situations. “They all voted for mine, because no one voted on management cards, and that wouldn’t happen on the universal ballot.”

Taxin’s victories were not indicative of his peers’ success in 2016, and perhaps the pendulum will swing back in their favor in the 2017 proxy season. Four activists have already gained board representation in 2017 and several have threatened to go all the way to a vote as annual meeting season begins.

Spread betting

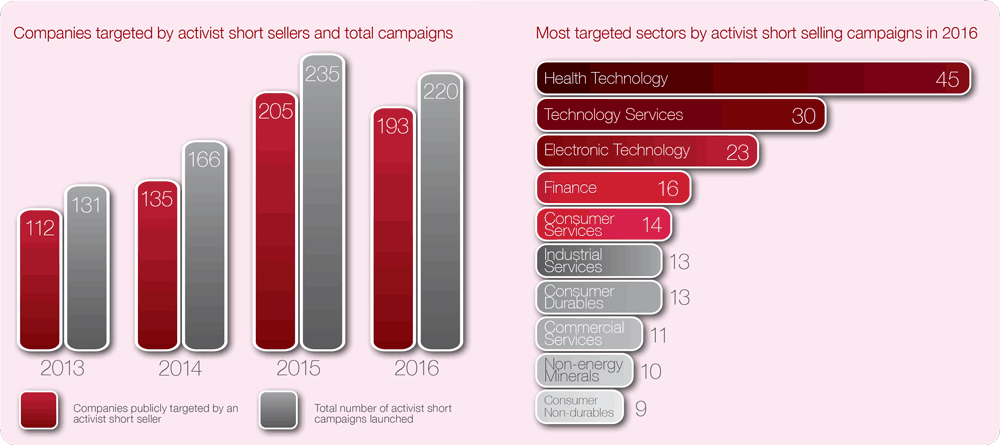

Over the past couple of years, we’ve watched activist short calls grow from a relatively unknown phenomenon to target 112 companies in 2013 and a whopping 205 in 2015, according to Activist Insight data. The question on all of our minds was whether activist short sellers’ momentum would continue at an equally fast trajectory. In fact, 2016 saw 193 companies targeted, slightly lower than the year prior. And, instead of adding to their campaigns at home, several prominent short sellers this year turned to new markets and began a year of laying the foundations for short campaigns to come.

Eyes on Asia

Most notably in 2016, activist short sellers flung open the doors to Japan, beginning with Well Investments Research’s campaign at Marubeni in December 2015. Well Investments went on to launch campaigns at three more Japanese companies in 2016.

It wasn’t long until prominent short sellers Muddy Waters Research and Glaucus Research took notice, each announcing an activist short campaign of their own; Horseman Capital Management and Oasis Capital Management also unveiled Japanese shorts in 2016, bringing the campaign from zero in late 2015 to a remarkable 11 by the end of 2016.

Discussing his turn to Japan, Well Investments’ Yuki Arai credited the country’s new focus on corporate governance as an opportunity to take a fresh look at mispriced assets. This attitude may have spilled over into the rest of the region; South Korea saw its first activist short less than three months after Arai first published in Japan, with the launch of Ghost Raven Research’s campaign at $10 billion biologics company Celltrion. The next month, we followed the first activist short campaign in Taiwan when The Street Sweeper discussed Himax Technologies.

Beginning a long road

Citron Research’s Andrew Left is a big exponent of short selling in Asia. When questioned on where he and his kind will look for opportunities in 2017, Left was decisive: “There is a lot of fraud in Japan,” he notes. Yet for Citron, Hong Kong, the favored domain of activist short sellers for several years, “is pretty closed,” after 2016 saw Left found guilty of using “sensationalist language” and making false claims—a verdict he says sanctioned him “for telling the truth.” Hong Kong is “still a different kind of market,” he argues.

Other prominent activist shorts seem to disagree. Anonymous Analytics wrote in a July report for Activist Shorts Research, before its acquisition by Activist Insight, that the road ahead for Hong Kong to clean up “remains long and will be littered with the corpses of more fraudulent companies to come.” Muddy Waters’ Carson Block is on the same page, having promised in December to seek out more Hong Kong targets on concerns of stock manipulation.

GeoInvesting, which has launched campaigns at over 30 companies in China and Hong Kong according to Activist Insight data, also pledged in March to continue cleaning up China based fraud—most recently combining with long activist Heng Ren Investments to air allegations against Sinovac Biotech.

But Left hopes Japan will be different. “With Abenomics, we’re closer and closer to cracking Japan,” he said. “Japan has been a very closed system for years. The shorts haven’t really worked it out to where they should, but once Japan learns that activist shorts actually add value, there is going to be a lot of opportunity there for shorts. But in the long run, that’s going to be very good for their markets.” Left added, “It’s a cleansing process.”

Shorts go global

Companies outside of Eastern Asia haven’t escaped scrutiny. The year also saw the first campaign at a Bahamas-headquartered company, with Richard Pearson targeting Nymox Pharmaceutical.

Further, Muddy Waters’ Block came through on his Fall 2015 promise to target the “ticking time bombs” of Western Europe, following a theme for 2016 of shorting heavily financially engineered companies. After the activist’s October 2015 short of $24 billion Swedish telecom company TeliaSonera, as well as its December 2015 short of French grocer Casino and Casino’s parent company Rallye, Muddy Waters delivered our second German short of 2016 with a campaign at media company Ströer in April.

However, beating Muddy Waters to the punch in Germany, which had not seen activist short activity since 2013, was a new, anonymous short seller called Zatarra Research & Investigations. The activist launched a relentless campaign in February against $6 billion payments company Wirecard, which saw a regulatory inquiry, the rise of an anonymous whistleblower and comments from noted short seller Bronte Capital, as well as reported legal action against both the short seller and the company.

Where to next?

At the same time, other activist shorts continued pursuing some of their most reliable targets. For the fourth year in a row, health technology companies were the most popular sector for shorting. Following Valeant Pharmaceuticals in 2015, activists such as Citron Research kept the conversation in 2016 focused on pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, including targets such as Express Scripts and AveXis.

Speaking with Activist Insight on shorts’ interest in health technology companies, Andrew Left of Citron Research noted that “the mega trend is ‘banks are the new pharma, and pharma is the new banks.’” He added that “any pharma company that has built its business on raising prices is gone.”

Behind the calls

Types of activist short sellers

According to Activist Insight data, activist short sellers are more often than not anonymous entities and funds. Much less often, activist short sellers are classified as single individuals launching a short campaign.

2014 was a banner year for the debut of new, anonymous shorts, which have since decreased slightly. The number of new funds unveiling an activist short strategy peaked in 2015, meanwhile, at 18. With fewer new activist short sellers of all types in 2016, the balance between fund manager and anonymous was more balanced than ever.

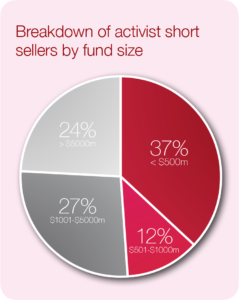

Size of funds

Short calls come from funds of all sizes, where total assets under management (AUM) figures are known. Perhaps surprisingly, the average activist short seller classified as a fund has a median AUM of $1.1 billion. But that hasn’t stopped smaller funds, particularly the 15 activist short funds with less than $500 million in known AUM. Funds in that category, including prominent short sellers like Bronte Capital and Kerrisdale Capital, have launched 70 campaigns so far since January 2013, which represents 10% of all campaigns and a remarkable 40% of campaigns launched by funds.

Location, location, location

More often than not, activist short sellers are based in the U.S., regardless of whether they are a fund, an individual or an anonymous entity. But as short sellers extend their global reach into new markets, so do the locations of the activists themselves. This year saw the debuts of short sellers located in Singapore, Canada, Hong Kong and the U.K.. Notably, the count of known U.K. activist short sellers doubled from two to four in 2016, and we saw the first known activist short seller based in Singapore.

The complete publication is available here.

Print

Print