Gail Weinstein is senior counsel and Philip Richter is a partner at Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP. This post is based on a Fried Frank publication by Ms. Weinstein, Mr. Richter, Steven Epstein, Warren S. de Wied, Christopher Ewan, and Brian T. Mangino. This post is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

As has been widely discussed over the past two years, the Delaware courts have moved toward substantially greater deference to board and stockholder decisions in M&A transactions. Other than in the case of transactions with controllers, there is significantly less risk today than in the past that a challenge (particularly post-closing) to a board decision to engage in a transaction will be successful; there is a far greater likelihood that litigation challenging a transaction will be dismissed at an early stage of litigation; and when there has been a pre-signing market check, there is considerably less risk that an appraisal award issued to dissenting shareholders will exceed the merger price.

- Appraisal. In appraisal proceedings, the courts are now likely to rely solely on the merger price in arm’s-length mergers where there was “meaningful competition”; and, indeed, there may be an increased risk of an appraisal award being below the merger price.

- Business Judgment Rule. In post-closing actions for damages challenging a non-controller merger, the “fully informed” approval of the disinterested stockholders should “cleanse” the transaction, even if the transaction had been approved by a board that was not independent and disinterested.

- Disclosure. The court appears to be showing less receptivity to the kinds of “tell me more” disclosure claims that proliferated in past years, generally applying a stricter standard than in the past for finding that claims of non-disclosure in connection with stockholder votes are meritorious.

Appraisal

The Delaware Court of Chancery appears to have confirmed and expanded its trend toward greater reliance on the merger price (and less reliance on discounted cash flow and related financial valuation analyses) to determine the appraised “fair value” of dissenting shares in cases involving arm’s length transactions that included a meaningful market check. Importantly, while the court, when it relies on the merger price, has not yet adjusted the merger price downward to exclude the value of merger synergies in any case (notwithstanding the appraisal statute’s requirement that value “arising from the merger itself” be excluded from fair value), in the January 2017 Lender Processing opinion, Vice Chancellor Laster encouraged respondent companies to present timely arguments, supported by a sufficient record, for such adjustments. Such adjustments, which would result in appraisal awards below the merger price (when the court relies solely on the merger price to determine fair value), would significantly increase the risk for stockholders in seeking appraisal.

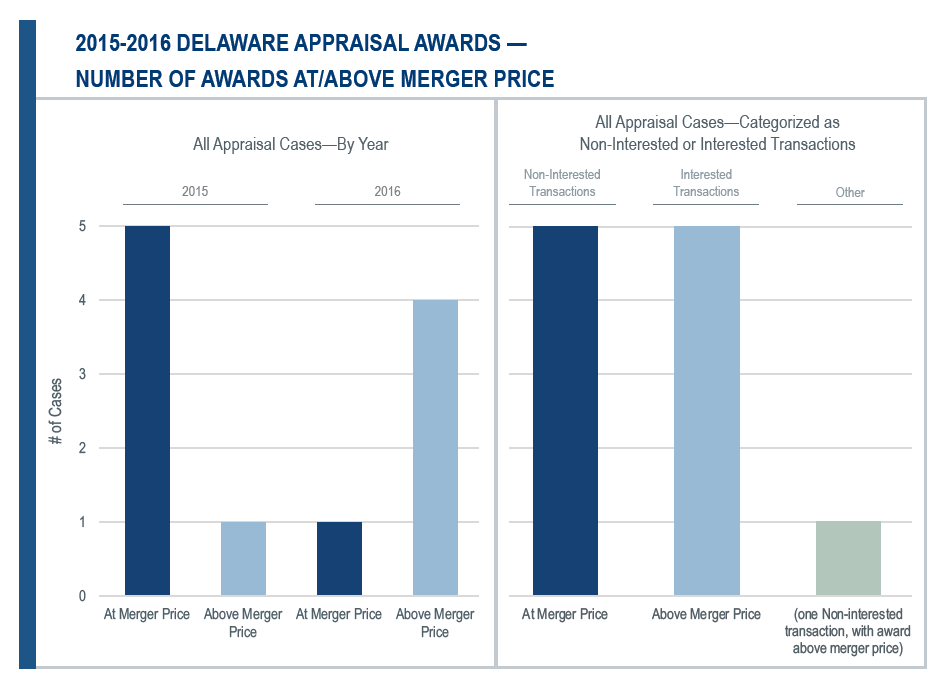

Use of the merger price. In 2015, the Court of Chancery relied on the merger price to determine appraised “fair value,” and issued awards equal to the merger price, in five out of the six appraisal decisions issued that year—CKx, Ancestry, AutoInfo, Ramtron, and BMC Software. In 2016, the court did not rely primarily on the merger price to determine “fair value,” and issued appraisal awards above the merger price in four of the five appraisal decisions issued (with premiums above the merger price, not including interest, of 10.7%, 26%, 8.4%, and 250%, respectively)—F&M Merchants, Dell, DFC Global, and ISN Software.

Nonetheless, 2016 reflected the court’s continued adherence to the previously established basic trend of reliance on the merger price in “non-interested” transactions involving a meaningful market check. Specifically, since 2010:

- In “interested transactions” (i.e., those involving a controlling stockholder, parent-subsidiary, management buy-out, or other element of self-interest on the part of the seller), the appraisal award frequently has been above (often, significantly above) the merger price. Further, although the sample size is quite small, (a) in the case of interested transactions where there was no effective market check and there were no minority shareholder protections in the sale process, the premium has averaged 138.4% (and in each case has been at or above 60%); while, (b) in the interested transactions where there was some attempt at a market check or minority protections (even if it were viewed by the court as flawed or weak), the premium above the merger price has averaged 19% (and in each case has been at or below 26%).

- In “non-interested transactions,” the appraisal award has been equal (or very close) to the merger price. In these cases, where the court deemed the sale process to have included “meaningful competition,” there has been no premium. Although, again, the sample size is quite small, in the cases where the court did not view the process as having included a meaningful market check (or, as occurred in cases before 2014, the court did not address the strength of the sale process), the appraisal award was sometimes above the merger price, but not by more than 10-15%.

Late-2016 appraisal decisions. The appraisal decisions issued in the last quarter of 2016 were:

- Dunwire v. F&M Merchants Bancorp (Nov. 10, 2016). In F&M Merchants, according to the court, the merger was “undertaken at the insistence of” a shareholder that was a controller of both the acquiror and the target company and it “was not the product of a robust sale process.” To determine appraised fair value, the court relied on a discounted net income model (a variant of the discounted cash flow model more typically utilized by the court when it has not relied on the merger price). The court determined fair value to be 10.7% higher than the merger price.

- Merion Capital v. Lender Processing Services, Inc. (Dec. 16, 2016). In Lender Processing, the merger was a non-interested transaction and there was “meaningful competition” in the sale process. Indeed, all of the factors the court has previously indicated would militate toward reliance on the merger price were present: many financial and strategic potential bidders were contacted, were provided with meaningful information, and were treated equally; the court’s DCF analysis (conducted as a double-check) was close to the merger price; the merger price represented a substantial premium over the unaffected market price of the company’s stock; and there was evidence of significant anticipated merger synergies with the strategic buyer, indicating that the merger price likely was even higher than “fair value” under the appraisal statute. The court relied entirely on the merger price and issued an appraisal award equal to the merger price.

New developments in 2016.

- Expanded reliance on the merger price when there has been “meaningful competition.” In Lender Processing, Vice Chancellor Laster held that even if the target company’s projections (that would be the basis of a financial valuation analysis) were viewed by the court as completely reliable, the court may rely exclusively on the merger price so long as the sale process involved “meaningful competition”—at least in the context of a case where all of the other facts and circumstances also support use of the merger price. Previously, the court had maintained that it would rely solely on the merger price only when both the merger price was an especially reliable indicator of fair value (because the target had been shopped) and a financial valuation was particularly unreliable (due to unreliable projections).

- More nuanced view of what may or may not constitute “meaningful competition.” Observers were surprised that the court chose not to rely solely on the merger price in Dell and in DFC Global, even though in both there had been a market check with competitive bidding.

- Rejection of reliance on the merger price in an “interested” transaction with competition—Dell. Dell involved a going-private management-buyout in which the company’s major stockholder (who was also the founder, CEO, and creator of the company’s turnaround plan for the future) would be acquiring 75% of the resulting company shares. The court viewed the “interested” nature of the transaction as undermining the reliability of the factor of competition in the sale process. The court relied on a DCF analysis and determined fair value to be 26% above the merger price.

- Rejection of reliance on the merger price in “non-interested” transaction with competition (due to special circumstances)—DFC Global. DFC Global involved a “non-interested transaction” with competitive bidding. The court rejected sole reliance on the merger price, however, due to what it viewed as highly unusual circumstances—namely, extreme regulatory uncertainty facing the company at the time of negotiation and consummation of the merger, as the payday loan industry was facing a complete regulatory overhaul that would potentially affect individual companies very differently. As that uncertainty also undermined the reliability of the company’s projections, the court utilized “a blend” of what it considered “three imperfect methodologies”—the merger price, a DCF analysis and a comparable analysis. The court determined fair value to be 8.4% above the merger price (which, given the small number of dissenting shares, represented an additional cost to the buyer of less than .03% of the transaction value).

- Some increased risk of an appraisal award being lower than the merger price. In the Lender Processing decision, Vice Chancellor Laster appeared to suggest an increased willingness on the court’s part to award less than the merger price when there are significant, well-documented expected merger synergies. Previously, the court had acknowledged the appropriateness of such adjustments based on the statutory prohibition against including in “fair value” any value “arising from the merger itself”; however, the court has not made such adjustments, apparently due to the practical difficulties involved. (These difficulties include determining which synergies “arise from the merger” as compared to being part of the “intrinsic value” of the company and determining to what extent their value was included in the merger price.) In Lender Processing, the court declined to make such an adjustment, but emphasized that the rejection was based on the company’s arguments for an adjustment having been made “too late”—i.e., “post-trial,” rather than “during the litigation.” We note that even financial buyer transactions may involve merger synergies that could support a downward adjustment in the merger price.

Business Judgment Rule

The Delaware courts continue their strong trend of early dismissal of post-closing challenges to non-controller M&A transactions—even in the context of difficult fact situations. In non-controller transactions approved by “fully informed” stockholders, the Delaware courts, applying the seminal 2015 Corwin decision, have applied the business judgment rule (BJR) and have dismissed cases at an early stage of litigation. The courts have clarified that, under Corwin, (a) the BJR should apply even if the board approving the transaction was not independent and disinterested, and (b) application of the BJR should result in dismissal of post-closing damages claims at the pleading stage of litigation.

Three late-2016 decisions exemplify the courts’ early dismissal of litigation notwithstanding difficult fact situations:

- Books-A-Million (Oct. 10, 2016)—please see the summary below of the Fried Frank Briefing analyzing this decision.

- OM Group Stockholders Litigation (Oct. 12, 2016). OM involved, in the words of the Court of Chancery, allegations that comprised “a disquieting narrative.” It was alleged that, in the face of a threat of shareholder activism, the OM board “rushed to sell the company on the cheap in order to avoid the embarrassment and aggravation of a prolonged proxy fight.” The plaintiffs’ contended that the OM board ignored the advice of its financial advisors that value would be maximized through separate sales of the company’s diverse business units to strategic buyers. Instead, according to the complaint, the board “deliberately shut out strategic acquirors in favor of a quick deal with a financial sponsor.” The board “hurried the pre-signing sale process and post-signing market check in a manner that ensured strategic buyers would have no time or desire to pursue piecemeal transactions.” The directors were “fueled by a desire to avoid a public confrontation with a vocal dissident shareholder by selling OM before the dissident could mount a proxy fight.” Further, the board “failed to manage conflicts among its contingently compensated investment bankers” (including one which had received significant fees from the buyer over the three years leading up to the merger) and the board relied on, and allowed the bankers to rely on, “manipulated projections that understated OM’s prospects in order to drive the bankers to conclude that a less-than-reasonable merger price was fair.” There were also allegations of incomplete and misleading disclosure in connection with the stockholder vote approving the merger. Notwithstanding the “disquieting narrative” (which, at the pleading stage, the court accepted as true), and that the sale invoked directors’ Revlon duties, the court concluded that the business judgment rule standard of review “because a majority of the fully informed, uncoerced, disinterested stockholders voted to approve the merger” and that, therefore, the complaint “must be dismissed.”

- Gamco Asset Management v. iHeartmedia Inc. (Nov. 23, 2016). Gamco invested in Clear Channel Outdoor Holding when it knew that CCOH was locked into “a contractually-created symbiotic relationship” with its former parent company, iHeartCommunications Inc. Through a set of intercompany agreements between CCOH and iHeart, the parties had agreed to position iHeart so that it could exercise significant control over nearly every aspect of CCOH’s operations. The agreements were entered into in anticipation of an IPO of CCOH and were highly favorable to iHeart. iHeart provided comprehensive management services to CCOH and had the right to pre-approve any significant acquisition or disposition of assets of CCOH and any significant financing by CCOH. Gamco brought suit, alleging that the board of CCOH breached its fiduciary duties and committed corporate waste when it approved a CCOH debt offering and asset sales in order to fund special dividends for the purpose of enabling iHeart (which was then its parent company) to address iHeart’s acute need for liquidity. The Court of Chancery held that the board’s decisions to take on debt, sell assets and declare dividends, which affected all CCOH stockholders equally, were protected by the business judgment rule.

New developments in 2016.

- Clarification that stockholder-vote cleansing “renders the business judgment rule irrebuttable.” The seminal 2015 Corwin decision held that, in a post-closing damages action, directors’ actions would be evaluated under the business judgment rule if the transaction had been approved by the fully-informed, uncoerced vote of the disinterested stockholders (unless the transaction was subject to entire fairness review). It was unclear at the time whether (i) application of the business judgment rule would be a rebuttable presumption or (ii) the business judgment rule would apply irrebuttably. The court indicated in Volcano (June 30, 2016), Larkin v. Shah (known as “Auspex”) (Aug. 25, 2016), and OM Group (Oct. 12, 2016) that application of the business judgment rule would be “irrebuttable;” and the Delaware Supreme Court has now resolved the issue, upholding Volcano (Lax v. Goldman Sachs, Feb. 9, 2017).

- Expanded view of transactions that can be “cleansed” by a stockholder vote. It also previously had not been clear whether, under Corwin, the exclusion from stockholder-vote cleansing of transactions subject to entire fairness review applied (i) only to transactions subject to entire fairness due to a controller standing on both sides of the transaction or (ii) also to transactions subject to entire fairness due to a majority of the directors who approved the transaction not having been independent and disinterested. In Auspex, Vice Chancellor Slights expressed the view that only controller transactions could not be “cleansed” (i.e., where the controller is a buyer or extracts a personal benefit not available to the other stockholders) by a stockholder vote. In Solera (Jan. 5, 2017), Chancellor Bouchard appeared to endorse that view (consistent with the view he expressed in the Court of Chancery decision in Corwin). Most recently, in Merge Healthcare (January 30, 2017), Vice Chancellor Glasscock also endorsed this approach. Thus, absent the Delaware Supreme Court addressing the issue, even a transaction approved by a majority of directors who are not independent and/or who have a personal interest in the transaction would be subject to the business judgment rule if the stockholders approved the transaction after adequate disclosure about the directors’ non-independence or personal interest.

- Application of stockholder-vote cleansing to tender offers. The Delaware Supreme Court has affirmed the Volcano holding that the tender of a majority of the disinterested stockholders’ shares into the first-step tender offer of a two-step merger under DGCL Section 251(h) would be treated as the equivalent of a stockholder vote. Therefore, cleansing under Corwin would apply in the context of a two-step merger without a stockholder vote.

Disclosure

- Seminal Trulia decision rejected disclosure-only settlements absent “plainly material” non-disclosure. In the landmark Trulia decision (Jan. 22, 2016), the Delaware Supreme Court significantly reduced the incentive for the plaintiffs’ bar to challenge the adequacy of proxy disclosure based on weak claims. The court established that it would reject disclosure-only settlements based on supplemental disclosure that would be “helpful” but was not “plainly material.” There was an immediate decline in litigation challenging M&A deals—with litigation brought in the first half of 2016 in 64% of deals valued over \$100 million, as compared to 90% or more in all other years since 2009 (other than 2015, with 84%—at a time that the result in Trulia was anticipated). Other courts have expressly endorsed the Trulia approach and rejected disclosure-only settlements, including the Seventh Circuit in Walgreen (Aug. 10, 2016). However, it still remains to be seen to what extent other jurisdictions will follow Delaware’s lead. For example, in a recent opinion (Gordon v. Verizon, Feb. 2, 2017), the New York Supreme Court Appellate Division iterated a new standard for evaluating non-monetary settlements that appears to vary from Delaware’s approach in potentially important respects.

- Stricter standard for materiality of disclosure. The Court of Chancery has emphasized in numerous 2016 decisions that information that is merely “helpful” is not material. Only information that a reasonable investor would view as important in deciding how to vote (i.e., that changes the “total mix” of available information) would be material. The court has not viewed as material what it has characterized as “details” regarding the sale process, including with respect to bankers’ analyses, that, in our view, in the past might well have been deemed material.

- Higher standard of materiality for post-closing disclosure claims. The Court of Chancery’s Nguyen decision (Sept. 28, 2016) clarified that the standard for rejecting dismissal of a disclosure claim in a pre-closing injunctive action is whether it is reasonably conceivable that the alleged nondisclosure was material; whereas, in a post-closing damages action, the standard is both that it is reasonably conceivable that the nondisclosure was material and that the non-disclosure constituted a breach of the directors’ duty of loyalty (i.e., that it would not constitute a breach of the duty of care, which could be exculpated). A duty of loyalty violation would occur in the context of a majority of the directors approving the transaction not having been independent and disinterested. Nguyen thus highlighted the narrowing circumstances under which plaintiffs can be successful in bringing post-closing disclosure claims.

Print

Print