Eduardo Gallardo is a partner focusing on mergers and acquisitions at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. This post is based on a Gibson Dunn Client Alert.

We reported in Gibson Dunn’s 2010 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update that the first half of 2010 was a busy one for securities litigation. That remained so in the second half of the year. The securities litigation landscape has featured ongoing battles in the trial courts regarding the scope and application of the Supreme Court’s decision in Morrison holding that purchasers on foreign exchanges cannot bring an action under Section 10(b) of the 1934 Act. As we discuss more fully below, Plaintiffs are employing various strategies in their attempts to bring actions on behalf of foreign purchasers in U.S. courts despite the Supreme Court’s explicit rejection of U.S. federal court jurisdiction for such claims, including initiating claims in state court, under state law, and even under foreign law, as well as arguing that a transaction is domestic when the investment decision is made in the U.S. To date, none of these strategies has been successful. We expect these disputes to continue in the district courts and to eventually make their way up to the courts of appeal.

Several other important securities cases are pending before the Supreme Court, or likely to be taken up by the Court in the current term. In Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, which was argued before the Supreme Court on December 7, 2010, the Court will revisit once again the extent to which a private plaintiff can bring an action under Section 10(b) of the 1934 Act against secondary actors. The case involves the question of whether a service provider (here, an investment adviser) that assisted in the drafting and issuance of another company’s prospectuses can be held liable for securities fraud, based upon the service provider’s alleged role in preparing the other company’s statements. The Siracusano case, discussed in our Mid-Year Update, involving materiality and whether there must be statistically significant information suggesting that a product is unsafe, is pending before the Court with oral arguments scheduled on January 11, 2011. As well, the Court recently granted a petition for writ of certiorari regarding the Fifth Circuit’s holding in Archdiocese of Milwaukee Supporting Fund Inc. v. Halliburton Co. (now captioned Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co.), the latest in a line of Fifth Circuit cases, beginning with Oscar Private Equity, requiring a showing of loss causation to obtain the benefit of the fraud-on-the-market presumption of reliance at the class certification stage. A circuit split has developed over the issue, with the Seventh Circuit in Schleicher v. Wendt explicitly rejecting Oscar and its progeny. The Supreme Court in Halliburton is likely to resolve the split.

With respect to filing and settlement trends, new securities class action filings have picked up significantly and the number of filings this year is on track to exceed last year’s total, according to statistics compiled by NERA Consulting. Settlement values continue to set new records, demonstrating the enduring risks that securities litigation poses to companies, officers and directors, and their insurers. Although the pace of new securities litigation filings related to the “credit crisis” continued to decline in 2010, there were nevertheless many significant cases in this area in the second half of 2010, some of which demonstrated an increasingly high bar being set by courts on plaintiffs to establish actionable misstatements and scienter at the pleading stage. Plaintiffs nevertheless secured some favorable results in 2010, including the first ever jury verdict in a credit crisis case.

Finally, in the world of SEC Enforcement, the Ninth Circuit’s reversal of a criminal conviction of a public company’s CFO in Goyal; the Fifth Circuit’s reversal of the dismissal of the SEC’s insider trading enforcement action against Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban; the recent highly-publicized raids of hedge fund’s offices in an SEC and DOJ insider trading investigation; and the SEC’s award of a $1 million bounty to a whistleblower in an insider trading action, all demonstrate the increasing strength of SEC Enforcement investigations and proceedings, which we believe will continue in 2011.

Filing & Settlement Trends

Filing Trends

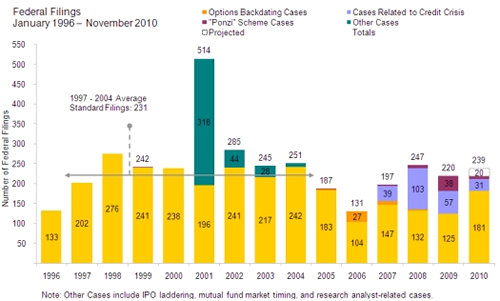

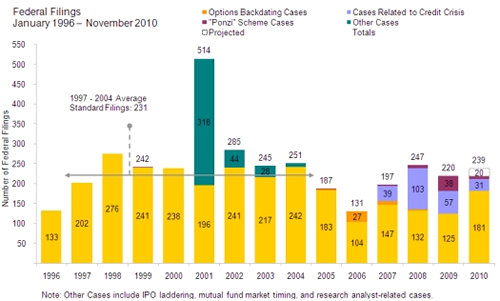

As noted in Gibson Dunn’s Mid-Year Update, the pace of securities class action filings had declined steadily from 2008 through the first half of this year. In the second half of 2010, however, NERA Economic Consulting is reporting that filings have picked up significantly and that the number of filings this year is on track to exceed last year’s total.

In particular, there have been 123 filings in the five months from July 1 through November 30, 2010, which already exceeds the 101 filings from January 1 through June 30, 2010. In all, NERA projects 239 filings in 2010, which would represent an increase from last year’s 220 filings.

Chart used by Permission of NERA.

NERA reports that the drop-off in filings related to the global financial crisis continued notwithstanding the overall uptick in filings–just 31 cases so far this year–compared to a high of 103 such cases in 2008. Nevertheless, securities class actions filed against financial firms still led the way with more filings than any other industry sector, although a majority of such suits were found by NERA to be unrelated to the global financial crisis.

NERA also finds that the increase in total filings in 2010 appears to stem from an increasing number of “standard” filings, which excludes filings related to the credit crisis, Ponzi schemes, and certain other special categories. 2010 also marked a large increase in the number of securities class actions filed against technology firms. Indeed, the amount of filings against electronic technology, technology services, and non-energy minerals firms doubled in 2010 over the prior year.

NERA also reports that 2010 will be the first year since 2005 that the Second Circuit does not lead the country in the number of securities class actions filed. Through the end of November, the Ninth Circuit had 62 filings and the Second Circuit had 49.

Settlement Trends

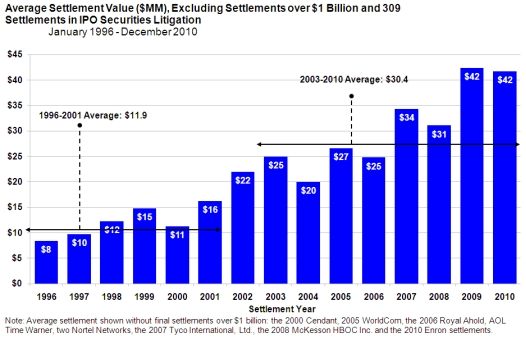

Although down from the first-half average of $209 million, NERA reports that the average settlement of securities class actions was still a record $109 million, exceeding the previous record of $80 million in 2006. NERA noted that the February 2010, $7.2 billion Enron settlement had a substantial impact on the average settlement in 2010.

When what NERA terms as “outliers” are removed, the average settlement this year was equal to last year, coming in at a record $42 million, as reflected in the chart below.

Chart used by Permission of NERA.

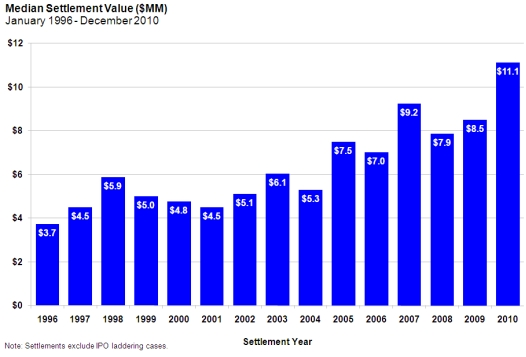

In the chart below, NERA reports that the median securities class action settlement was also a record high of $11.1 million, representing a significant increase over last year’s median of $8.5 million.

Chart used by Permission of NERA.

In the chart below, NERA reports record-high median investor losses in 2010 of $604 million. Importantly, however, NERA also reports that the median settlement amount as a percentage of median investor losses has continued to decline from the five-year high water mark set in 2008, and is well below levels from the 1990s. In 2010, the ratio of median settlement amounts to median investor losses was just 2.4%. (NERA calculated investor losses by comparing the return on the defendant company’s stock to the return on the S&P 500 over the class period, and by using a proportional decay trading model to estimate the number of affected shares of common stock.)

Chart used by Permission of NERA.

Supreme Court Developments

As we reported in our Mid Year Update, the Supreme Court issued several significant securities opinions in its 2009-2010 Term. Several cases in the 2010-2011 Term promise to be similarly important.

Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders

On December 7, 2010, the United States Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, U.S. No. 09-525, to resolve whether a secondary actor–a service provider (here, an investment adviser) that assisted in the drafting and issuance of another company’s (here, mutual funds’) prospectuses–could be held liable for securities fraud, based upon the service provider’s alleged role in preparing the other company’s statements. Petitioner Janus Capital Management LLC (JCM), a subsidiary of petitioner Janus Capital Group Inc. (JCG), is a registered investment adviser that advises and handles the day-to-day operations of the Janus family of mutual funds. A purported class of JCG shareholders alleged that Janus Funds’ prospectuses contained misrepresentations regarding market timing, and that JCM is liable for allegedly participating in the preparation of those prospectuses.

In oral argument before the Supreme Court, Janus, represented by Gibson Dunn, argued that JCM should not be liable because it made no statements–the prospectuses were approved and “adopted” by the Funds’ board of trustees, and therefore the issuer “made” the statements, not the service provider (JCM). Janus argued that extending liability to JCM in such circumstances would run contrary to both Central Bank of Denver, N.A. v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, N.A., 511 U.S. 164 (1994), which held that private plaintiffs could not bring a securities fraud suit against secondary actors (such as service providers) that allegedly assisted in the fraudulent behavior, and also Stoneridge Investment Partners, LLC v. Scientific-Atlantic, Inc., 552 U.S. 148 (2008), in which the Court rejected a private right of action for aiding and abetting securities fraud. Respondent countered that entities like JCM must be held liable when they engage in intentionally fraudulent conduct; otherwise, advisers and other mutual fund service providers could freely engage in fraud through shell parent companies. Respondent also urged a broad interpretation of the word “make,” arguing that a defendant “makes” a false or misleading statement if it is involved in creating or composing the statement. The United States also appeared and argued, siding with First Derivative Traders.

At least two justices seemed to agree with Janus. Justice Scalia observed that JCM “didn’t make the statements” and the prospectuses “didn’t go out under their name.” He described JCM’s role as “just like writing a speech for somebody.” Similarly, Justice Kennedy said that he saw “nothing . . . in the record that would justify” attributing the alleged misstatements to JCM. Justice Sotomayor, however, voiced concerns over whether a party in JCM’s situation would be able to avoid liability even though it intentionally engaged in fraudulent conduct. Other justices, including Justices Alito and Kagan, expressed concern about the possibility that if entities like JCM could not be liable in these circumstances, it is possible that victims of fraud might not have redress.

Siracusano v. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc.

In our Mid-Year Update, we reported on the Supreme Court’s granting of a writ of certiorari to review the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Siracusano v. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc., 585 F.3d 1167 (9th Cir. 2009). In Siracusano, the district court held that information in adverse event reports regarding the safety of a pharmaceutical product is not material unless such reports provide reliable statistically significant information that a drug is unsafe, and it found that 12 user complaints was not statistically significant. The Ninth Circuit reversed, rejecting the statistical significance standard and holding that an omitted fact is material if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important and noting the Supreme Court’s rejection of a bright-line materiality standard in Basic, Inc. v. Levinson. The Ninth Circuit’s decision created a split of authority with the First, Second, and Third Circuits, which have held that drug companies have no duty to disclose adverse event reports until those reports provide statistically significant evidence that the adverse events may be caused by, and are not simply randomly associated with, a drug’s use. The Supreme Court granted certiorari on June 14, 2010.

The SEC and Solicitor General’s office submitted an amicus brief in November arguing that the statistical significance standard conflicts with Basic because other evidence can suggest a causal link between use of a drug and an adverse effect, and a reasonable investor may consider that information important even if it does not prove that the drug causes the effect (for example, it can affect the product’s commercial viability). Additionally, the brief argues that the Supreme Court in Basic and TSC v. Northway rejected bright-line tests regarding materiality at the motion to dismiss stage in favor of a more flexible approach allowing the consideration of a number of factors. Oral arguments before the Supreme Court are scheduled on January 11, 2011.

Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co.

As noted in Gibson Dunn’s Mid-Year Update, the Fifth Circuit confirmed that to certify a Rule 23 class for a Section 10(b) claim based on the fraud-on-the-market presumption, the plaintiff must establish loss causation. See Archdiocese of Milwaukee Supporting Fund Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 597 F.3d 330 (5th Cir. 2010) (reaffirming Oscar Private Equity Investments v. Allegiance Telecom, Inc., 487 F.3d 261 (5th Cir. 2007)). On May 13, 2010, 2010, plaintiffs in Halliburton, now known as Erica P. John Fund, Inc., filed a petition for writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court and in December–at the request of the Court–the SEC and DOJ filed an amicus brief, encouraging the Court to take up the case. The government argued that the Fifth Circuit’s approach improperly considers the merits at the class certification stage without any reason to do so under Rule 23, and that certiorari should be granted to resolve a split between the approach of the Fifth Circuit, the Seventh Circuit (which rejected Oscar outright in Schleicher v. Wendt, 618 F.3d 679 (7th Cir. 2010)), and the Second Circuit (which allows some consideration of the merits at the class certification but does not require the putative class representative to prove loss causation, see In re Saloman Analyst Metromedia Litig., 544 F.3d 474, 479, 483 (2d Cir. 2008)).

The Supreme Court granted certiorari on January 7, 2011, and the case is likely to be argued in the Spring.

Extraterritoriality of U.S. Securities Laws

One of the most significant developments in 2010 was the Supreme Court’s holding in Morrison v. National Australia Bank, — U.S. —, 130 S. Ct. 2869 (2010), that Section 10(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act does not extend to purchases of securities on foreign exchanges, regardless of whether there was a domestic connection to the alleged fraudulent statements. The Supreme Court established a “transactional” rule, holding that Section 10(b) applies only to “the purchase or sale of a security listed on an American stock exchange, and the purchase or sale of any other security in the United States.” Id. at 2884. The Supreme Court rejected the Second Circuit’s “conduct and effects” test, which had construed Section 10(b) to apply to claims on foreign-traded securities if there was a sufficient domestic nexus–either when wrongful conduct (such as the dissemination of misstatements) occurred in the United States, or the conduct’s effects were felt here. Id. at 2879. The Supreme Court held that the Second Circuit’s formulation ignored the “presumption against extraterritoriality,” which provides that absent a clear intent of Congress that a statute apply to overseas conduct, the statute should be construed not to do so. The Supreme Court found that nothing in Section 10(b) suggests it applies abroad. Id. at 2882.

Judicial Response to Morrison

Following Morrison, plaintiffs have asserted a number of arguments that purchases on foreign exchanges should still be subject to Section 10(b) claims — all of which, to date, the lower courts have rejected.

First, Plaintiffs in several cases have argued that Morrison‘s requirement of a “domestic transaction” is satisfied where the plaintiffs are domestic and make their investment decisions in the U.S. The courts have unanimously rejected this construction.

- Plumbers’ Union Local No. 12 Pension Fund v. Swiss Reinsurance Co., No. 08 Civ. 1958 (JGK), 2010 WL 3860397 at *10-16 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 4, 2010) (“[A]s a general matter, a purchase order in the United States for a security that is sold on a foreign exchange is insufficient to subject the purchase to the coverage of section 10(b) of the Exchange Act. There may be unique circumstances in which an issuer’s conduct takes a sale or purchase outside this rule, but the mere act of electronically transmitting a purchase order from within the United States is not such a circumstance.”).

- In re Société Generale Sec. Litig., No. 08 Civ. 2495, 2010 WL 3910286, at *9-10 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 29, 2010) (“By asking the Court to look to the location of ‘the act of placing a buy order,’ and to . . . ‘the place of the wrong,’ Plaintiffs are asking the Court to apply the conduct test specifically rejected in Morrison.”). The court also sua sponte dismissed claims based on American Depository Receipts traded over-the-counter in the U.S., reasoning that a trade in ADRs was a “predominantly foreign securities transaction.” Id., 2010 WL 3910286, at *6.

- Cornwell v. Credit Suisse Group, No. 08 Civ. 3758, 2010 WL 3291800, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 11, 2010) (Section 10(b) does not apply “to any claims related to foreign securities trades executed on foreign exchanges even if purchased by American investors”).

- Stackhouse v. Toyota Motor Co., No. CV 10-0922, 2010 WL 3377409, at *1 (C.D. Cal. July 16, 2010) (“`[D]omestic transactions’ or ‘purchase[s] or sale[s] . . . in the United States’ means purchases and sales of securities explicitly solicited by the issuer within the United States rather than transactions in foreign-traded securities where the ultimate purchaser or seller has physically remained in the United States. . . . [B]ecause the actual transaction takes place on the foreign exchange, the purchaser or seller has figuratively traveled to that foreign exchange — presumably via a foreign broker — to complete the transaction.”).

- Quail Cruises Ship Mgmt. Ltd. v. Agencia de Viagens CVC Tur Limitada, No. 09-23248-CIV, 2010 WL 3119908, at *3 (S.D. Fla. Aug. 6, 2010) (Morrison bars parties from contractually selecting federal law for a securities transaction that otherwise has no relationship to the U.S.).

Second, plaintiffs in several cases have argued that Morrison is satisfied so long as the issuer lists some ordinary shares on a U.S. exchange, even if the particular shares that class members purchased on foreign exchanges. This “listing” argument has not yet succeeded in any case.

- In re Alstom SA Sec. Litig., No. 03 Civ. 6595 (VM), 2010 WL 3718863 at *2-3 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 14, 2010) (“[This] argument presents a selective and overly-technical reading of Morrison that ignores the larger point of the decision. Though isolated clauses of the opinion may be read as requiring only that a security be ‘listed” on a domestic exchange for its purchase anywhere in the world to be cognizable under the federal securities laws, those excerpts read in total context compel the opposite result.”).

- Sgalambo v. McKenzie, No. 09 Civ. 10087, 2010 WL 3119349, at *17 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 6, 2010) (although the Canadian issuer’s common stock was traded on both U.S. and Canadian exchanges, plaintiffs conceded that Morrison “forecloses any potential class members who purchased . . . on a foreign exchange . . . from recovering in this action,” and the court agreed.).

- In re Celestica Inc. Secs. Litig., No. 07 CV 312 (GBD), 2010 WL 4159587, at *1 n.1 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 14, 2010) (where issuer’s common stock traded on both domestic and foreign exchanges; claims dismissed as to purchases on foreign exchanges).

Third, plaintiffs in some cases have attempted to assert claims under foreign law in U.S. federal courts. These claims may be dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, or on grounds of international comity or forum non conveniens.

- In re Alstom SA Securities Litig., No. 03 Civ. 6595 (VM), 2010 WL 3718863, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 14, 2010) (the court dismissed French law claims by a discretionary denial of supplemental jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1367(c), saying that inserting French claims following Morrison would effectively restart a seven-year old litigation and require application of complex French law).

- In In re Toyota Motor Corp. Securities Litigation, No. 10-922 DSF (MANx) (C.D. Cal.), (plaintiff purchasers of Toyota’s foreign-traded common stock have asserted statutory claims under Japanese law, claiming jurisdiction under the Class Action Fairness Act as well as supplemental jurisdiction under Section 1367. Toyota is expected to file a motion to dismiss in January 2011.).

Finally, at the very end of the year, Judge Baer in the Southern District of New York held that swap agreements traded domestically but referencing underlying securities traded on a foreign exchange do not fall within Morrison‘s second prong–i.e., the “purchase or sale of any other security in the United States”–because the “economic reality” is that the swaps were transactions in foreign securities. Elliott Associates v. Porsche Automobil Holding SE, No. 10-cv-04155-HB (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 30, 2010). In Elliott, the plaintiffs entered swap agreements with unknown third parties that were tied to the performance of foreign-traded stock in Volkswagen. Although Section 10(b) can apply to swap agreements, and plaintiffs entered these swap agreements domestically, the court held that plaintiffs could not bring a claim under Section 10(b) because the referenced shares were traded on a foreign exchange.

The court stated that “[s]ince the economic value of securities-based swap agreements is intrinsically tied to the value of the reference security, the nature of the reference security must play a role in determining whether a transnational swap agreement may be afforded the protection of § 10(b). Here, Plaintiffs’ swaps were the functional equivalent of trading the underlying VW shares on a German exchange. Accordingly, the economic reality is that Plaintiffs’ swap agreements are essentially ‘transactions conducted upon foreign exchanges and markets,’ and not ‘domestic transactions’ that merit the protection of § 10(b).” The court also emphasized that the swap agreements did not involve the issuer, and stated that it was “loathe to create a rule that would make foreign issuers with little relationship to the U.S. subject to suits here simply because a private party in this country entered into a derivatives contract that references the foreign issuer’s stock.”

It remains to be seen whether the “economic reality” test articulated in Elliott Associates v. Porsche will affect the analysis for cases outside the swap context.

Legislative Response to Morrison

The Dodd-Frank Act attempted to revive extraterritorial application of the securities laws’ anti-fraud provisions in SEC and DOJ enforcement actions. Section 929O of Dodd-Frank amends the 1933 Act, the 1934 Act and the Investment Company Act of 1940 to provide federal court jurisdiction in any action brought by the SEC or the U.S. Attorney involving (1) conduct within the United States that constitutes “significant steps” in furtherance of the violation, even if the transaction occurs outside of the United States and involves only foreign investors or foreign advisers, or (2) conduct occurring outside the United States that has a foreseeable substantial effect within the United States. These provisions were drafted before the Supreme Court issued its decision in Morrison and were enacted into law after the opinion. Interestingly, they are phrased in terms of federal courts’ “jurisdiction.” Morrison made clear, however, that the extraterritorial scope of Section 10(b) is a matter of statutory interpretation, not jurisdiction. Consequently, Dodd-Frank appears to have created jurisdiction for hypothetical enforcement actions that are not currently authorized by the 1934 Act.

Secondary Liability

Outside of Janus Capital v. First Derivative Traders, there were a handful of decisions touching on secondary liability. In King County, Washington v. IKB Deutsche Bank Industriebank AG, No. 09-Civ-8387, 2010 WL 4366191 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 29, 2010), the court denied a service provider’s motion to dismiss a claim for common law fraud, and held that alleged misstatements could be attributed to it under the “group pleading” doctrine. The court held that plaintiffs sufficiently alleged that defendant Morgan Stanley was directly responsible for the creation, structure, and maintenance of the investment vehicle at issue; made allegedly false and misleading statements about ratings that were later communicated to investors; and was directly involved in creating the core deal documents disseminated to private investors. Morgan Stanley argued that it could not be liable because another entity, not Morgan Stanley, actually made and issued the alleged misstatements and therefore plaintiffs had pled, at most, that Morgan Stanley was merely a secondary actor of the primary fraud. Morgan Stanley relied on Pacific Investment Management Co. LLC v. Mayer Brown LLP, 603 F.3d 144 (2d Cir. 2010), which as we explained in our Mid-Year update, had held the law firm Mayer Brown could not be liable for securities fraud where it was not alleged to have made any false statements attributed to it at the time of dissemination. But the King County court disagreed, and held that Morgan Stanley’s alleged role in this case “far exceeded” merely providing or distributing the alleged misstatements, and instead that Morgan Stanley could be considered an “insider” according to the group pleading doctrine. The court opined that neither the PSLRA nor Central Bank “preclude[s] group pleading or require[s] that each individual defendant actually make the representation,” although the court did note that there is “some tension” between the group pleading doctrine and Central Bank.

Safe Harbor For Forward-Looking Statements

In our Mid-Year Update, we reported on the Ninth Circuit’s decision in In re Cutera Sec. Litig., -610 F.3d 1103 (9th Cir. June 30, 2010) (holding that forward looking statements accompanied by meaningful cautionary language are encompassed by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (“PSLRA”) safe harbor regardless of the state of mind of the person making the statement) and the Second Circuit’s decision in Slayton v. American Express Co., 604 F.3d 758 (2d Cir. 2010) (holding that that defendants were not entitled to protection under the meaningful cautionary language prong because their cautionary language was too vague, but affirming dismissal under the actual knowledge prong because plaintiffs failed to plead facts supporting a strong inference that the statement was made with actual knowledge that it was false or misleading). In the second half of 2010, the Third Circuit and a number of district courts rendered decisions interpreting the meaning of “forward-looking statement.”

- In In re Aetna, Inc. Securities Litigation, 617 F.3d 272 (3d Cir. 2010), the Third Circuit affirmed dismissal of a Section 10(b) claim against an insurance company based on allegedly misleading statements about underwriting practices and premium pricing. It held that the statements came within the safe harbor because they were forward-looking and were accompanied by meaningful cautionary statements. The statements “were partly historical and partly present-tense,” and the court acknowledged that mixed present/future statements are “not entitled to the safe harbor with respect to the statement[s] that refer[] to the present.” The present-tense portions at issue were indistinguishable, however, from the statements’ assertions about the future. “[T]o the extent [they] said anything about current price of premiums, [the statements] did so in the form of a projection . . . . Statements about future profitability and assumptions underlying management’s expectations about the future fall squarely within the definition of forward-looking statements.” Id. at 281. Having found that the statements were forward-looking, the court determined that they were accompanied by meaningful cautionary statements, and alternatively, were immaterial. Because no reasonable investor could have relied on the statements and the statements could not have meaningfully altered the total mix of information available to the investing public, the court found the safe harbor would apply even if the cautionary language had been inadequate.

- In Gissin v. Endres, — F.Supp.2d —, 2010 WL 3468508 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 1, 2010), the defendant predicted that because the company had sufficient capital on hand, “we think working capital will stay about where it was for the balance of the year.” 2010 WL 3468508, at *8 & n.106. The court determined that statements describing existing capital were present facts, but their veracity was not disputed. As to the allegedly false portions, the court found that terms such as “expectation” and “we feel we will” sufficiently designated the statements as forward-looking. The court reasoned that “defendants’ statements in the instant case refer to present circumstances only as a basis for forecasting future performance, not as a guarantee of the status quo.” Id. & n.108. The court concluded that those statements were accompanied by sufficient cautionary language and dismissed the suit.

- In In re Bare Escentuals, Inc., — F. Supp. 2d —, 2010 WL 3893622 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 30, 2010), the court found that “future projections with regard to the Company’s financial guidance and/or general future expenditures” contained in various press releases “easily” met the definition of forward-looking statements. Id. at *24. The court also held that the statements were accompanied by meaningful cautionary language, in part because the press releases incorporated by reference cautionary language contained in the company’s Form 10-Ks. Id. at *15.

- In In re Accuracy, Inc. Sec. Litig., 21010 WL 3447588 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 31, 2010), the court held that statements were forward-looking because they were prefaced with terms of belief and probability. The court found that defendants’ prediction that there was a “substantially high probability” of converting certain contingent contracts in backlog into future revenue was forward-looking, even though it was based on present facts about the backlogged contracts. Id. at 9. Defendant’s emphasis on contingency factors potentially affecting the prediction led the court to conclude that the statements were forward-looking and protected under safe harbor. Id.

- In Sgalambo v. McKenzie, — F. Supp. 2d —, 2010 WL 3119349 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 6, 2010), by contrast, the court held that defendants’ statements predicting the future production value of natural gas wells were not forward-looking. Defendants had reported “positive test results” indicating the wells would be economically productive, but allegedly failed to also include negative information that would have undermined their predictions. Id. at 9. The court found that statements reporting test results from the wells and predicting future well performance based on those results “incorporate[d] forward-looking aspects into statements of present fact.” Based on that conclusion, the court held that the safe harbor was inapplicable. Id. at 11 & n.150 (characterizing as non-forward-looking the statement that, based on recently completed tests, “[t]he ‘Victory’ well has an estimated flowing rate of over 100 mmscf/d of natural gas and is condensate rich”). The Sgalambo case illustrates the somewhat pliable nature of the question whether a statement is truly “forward looking.” The court may have been influenced by allegations that defendants intentionally omitted the contrary data undermining their predictions, and therefore strained to construe the predictions as statements of present fact so as to avoid the safe harbor.

- In Sawant v. Ramsey, 2010 WL 3937403 (D. Conn. Sept. 28, 2010), the court found that the safe harbor was inapplicable because the statements at issue could reasonably be interpreted as misstatements of present fact. Id. at *14. This was because the statements at issue, which were couched as predictions of a contract’s impact, implied that such a contract existed, when it did not. Id. Moreover, the court found that a “boilerplate safe harbor provision” included in the press release at issue would not have constituted meaningful cautionary language, as it referred only to risks associated with generalized market conditions, and did not alert the reader to the “nascence of the touted agreement.” Id. at *15.

- Finally, in Allstate Life Ins. Co. v. Robert W. Baird & Co., Inc., — F. Supp. 2d —, 2010 WL 4581242, at *15 (D. Ariz. Nov. 4, 2010), the court held that the safe-harbor did not apply because the issuer was “not subject to the reporting requirements of the Exchange Act.”. The court cited 15 U.S.C. 78u-5(a), which limits the safe harbor to an issuer “that at the time that the statement is made, is subject to the reporting requirements of section 78m(a) of this title or section 78o(d) of this title.” Id. Further, the court stated, the issuer must actually have “properly filed a registration statement with the SEC and must be in compliance with any applicable reporting requirements. Id. (citing 15 U.S.C. §§ 78l , 78m(a), 78o(d).

PSLRA Discovery Stay

In our Mid-Year Update, we reported on a number of decisions from the first half of the year regarding the PSLRA’s automatic stay of discovery. Since that time, courts have issued the following notable decisions.

- In American Bank v. City of Menasha, — F.3d —, 2010 WL 4812811 (7th Cir. Nov. 29, 2010), the Seventh Circuit addressed the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (SLUSA) provision that amended the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) to authorize the district court to “stay discovery proceedings in any private action in a State court, as necessary in aid of its jurisdiction, or to protect or effectuate its judgments, in an action subject to a stay of discovery pursuant to [the PSLRA]” See 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4(b)(3)(D). The plaintiff bank and other bondholders brought a federal securities class action against the City of Menasha, Wisconsin, which had defaulted on short-term bonds it had issued to convert an electric power plant to a steam-generating plant. The bank submitted a request to the City pursuant to Wisconsin’s public records law to inspect a large number of records relating to the conversion project and obtained an order from state court compelling the City to comply with the request. The district court granted the City’s motion to stay the order pursuant to the SLUSA amendment to the PSLRA discovery stay. In an opinion authored by Judge Posner, the Seventh Circuit held that public records requests are not “discovery” and the statutes’ purpose of preventing “settlement extortion” did not apply because the costs associated with responding to a public records request under Wisconsin law are charged to the requesting party. See American Bank v. City of Menasha, 2010 WL 4812811 at *3-*4.

- In Lindner v. American Express Co., No. 10 Civ. 2228, 2010 WL 4537819 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 9, 2010), the court rejected plaintiffs’ argument that the PSLRA stay should be lifted pursuant to the evidence preservation exception. The court reasoned that although the statute provides that the automatic stay can be lifted to preserve evidence, “there must be ‘imminent as opposed to merely speculative’ risk that evidence will not be preserved.” Id. at *2 (citing cases). Because plaintiff offered no reasonable basis for the court to conclude that defendants had not complied with their statutory obligation under the PSLRA to preserve evidence, the court denied plaintiff’s motion to lift the stay. Id.

- In Anwar v. Fairfield Greenwich Ltd., — F. Supp. 2d. —, 2010 WL 3431126 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 20, 2010), the court held that the PSLRA stay does not apply to arbitration proceedings. The plaintiff investment firms were respondents in a AAA arbitration brought by investors whose funds were invested in the Madoff ponzi scheme. Among other things, the investment firms sought an order requiring that discovery be stayed in the arbitration. The court found that neither the PSLRA nor SLUSA contemplates extending the stay to arbitrations. Additionally, the court noted that even if all the motions to dismiss pending in the federal case were granted, it would not bar document production in the arbitration. Accordingly, the court denied the investment firms’ motion. See id. at *13-*14.

Subprime and “Credit Crisis” Litigation

The pace of new securities litigation filings related to the so-called “credit crisis” continued to decline in 2010, with only 31 such cases filed through November as compared to 57 filed in 2009 and 103 in 2008, according to NERA. Nevertheless, there were many significant cases in this area in the second half of 2010, some of which demonstrated an increasingly high bar being set by courts on plaintiffs to establish actionable misstatements and scienter at the pleading stage. (We reported on several cases decided in the first half of the year in our Mid-Year Update.) Plaintiffs nevertheless secured some favorable results in 2010, including the first ever jury verdict in a credit crisis case.

- Starting with the positive for defendants, in NECA-IBEW Health & Welfare Fund v. Goldman, Sachs & Co. et al., — F. Supp. 2d —, No. 08-CV-10783 (MGC), 2010 WL 4054149 (S.D.N.Y Oct. 14, 2010), the court dismissed section 11 claims because plaintiff purchasers of mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”) failed to allege any diminution of cash flow payments due under the MBS they purchased, and thus they could not show a cognizable injury. The court rejected plaintiffs’ argument that they had been harmed by a decline in the MBS’ resale value because the MBS were issued with the express warning that they might not be resalable. The court distinguished New Jersey Health Fund v. DLJ Mortgage Capital, Inc., No. 08 Civ. 5653 (PAS), 2010 WL 1473288 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 29, 2010), which permitted a similar claim to proceed, because in that case there was no express warning that the MBS might not be illiquid.

- Courts continued to reject lead plaintiffs’ arguments that they have standing to sue over MBS offerings they did not invest in simply because the securitizations were issued pursuant to shelf registration statements. See Boilermakers Nat’l Annuity Trust Fund v. WaMu Mortg. Pass Through Certificates, Series AR1, No. 09-CV-00037 (MJP), 2010 WL 3815796 (W.D. Wash. Sept. 28, 2010); Maine State Ret. Sys. v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., — F. Supp. 2d. —, No. 2:10-CV-00302 (MRP), 2010 WL 4452571 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 4, 2010). The court in Countrywide explained that because the prospectus supplements contain the descriptions of the unique mortgage pools underlying the MBS, plaintiffs’ claims relied on disclosures made in the prospectuses and not a common shelf registration. The Countrywide court also noted that every court to address this issue has reached the same conclusion.

- In Footbridge Ltd. Trust v. Countrywide Home Loans, Inc., No. 09-CV-04050 (PKC), 2010 WL 3790810 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 28, 2010), the court dismissed with prejudice a complaint asserting claims under section 10(b) that challenged disclosures made in connection with two offerings of Countrywide MBS. The court followed the Fifth Circuit’s decision in Lone Star Fund v. (U.S.) L.P. v. Barclays Bank PLC, 594 F.3d 383, 389-90 (5th Cir. 2010), concluding that the offering documents did not promise unequivocally that loans in the mortgage pool would comply with guidelines, but rather that they either did so or would be cured upon request. The court also found that the plaintiffs’ general claims about Countrywide abandoning its underwriting guidelines were not tied to loans in the particular securitizations at issue.

- Claims added by new plaintiffs attempting to cure standing issues have generally been dismissed early on in litigation. This trend continued in In Re Wells Fargo Mortgage-Backed Certificates Litig., No. 09-CV-1376 (LHK), 2010 WL 4117477 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 19, 2010), where the court declined to toll claims asserted by newly added plaintiffs because the original named plaintiffs had no standing to bring the claims in the first place. After the court dismissed Section 11 claims related to MBS offerings in which plaintiffs had not invested, new plaintiffs that had invested in the MBS joined the lawsuit in an attempt to save the claims. The court rejected this tactic, holding that “American Pipe and the cases interpreting it support the declination to extend tolling to claims over which the original names Plaintiffs asserted no facts to supporting standing.” The court distinguished In re Flag Telecom Holdings, Ltd. Sec. Litig., 352 F. Supp. 2d 429, 455 (S.D.N.Y. 2005), which permitted tolling of claims dismissed for lack of standing because there the original plaintiffs had Section 11 standing, but not Section 12 standing, whereas in Wells Fargo the original plaintiffs had no standing to assert any claims over the offerings at issue.

- In Vining v. Oppenheimer Holdings, Inc. et al., No. 08 Civ. 4435 (LAP), 2010 WL 3825722 (S.D.N.Y Sept. 29, 2010), the court dismissed for failure to adequately plead scienter plaintiffs’ Section 10(b) claims alleging Oppenheimer made misleading statements about the liquidity of its auction rate securities (“ARS”). In weighing competing inferences, the court found it was more probable that Oppenheimer simply did not foresee the “wholly unprecedented collapse” of the ARS market, and thus there was insufficient evidence to find a conscious or reckless intent to defraud. The court also found that general allegations of Oppenheimer’s purchases of ARS, without identifying a specific increase in purchases during the relevant time period or the non-public information purportedly used by traders, was insufficient to find the motivation necessary for scienter.

- And in Woodward v. Raymond James Fin., Inc., — F. Supp. 2d —, No. 09-CV-5347 (RPP), 2010 WL 3239411 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 16, 2010), the court similarly dismissed a putative class action complaint alleging defendants made material misrepresentations about the adequacy of the subsidiary’s loss reserves and the quality of its loan portfolio because there were insufficient allegations of actionable misstatements or scienter.

- Several defendants were able to knock out substantial parts of lawsuits, but left enough of the case intact to give plaintiffs hope. For example, in In re Fannie Mae 2008 Sec. Litig., — F. Supp. 2d —, Nos. 08 Civ. 7831 (PAC), 09 MD 2013 (PAC), 2010 WL 3825713 (S.D.N.Y Sept. 30, 2010), the court dismissed two-thirds of plaintiffs’ remaining securities fraud claims. First, the court dismissed claims based on allegations of misleading statements about Fannie Mae’s subprime and Alt-A mortgage exposure because public disclosures contained sufficient cautionary language, plaintiffs failed to explain why the purported misstatements were false, and plaintiffs failed to adequately plead scienter. Second, the court dismissed claims based on allegations that Fannie Mae issued materially misleading financial statements because plaintiffs had not pleaded sufficient facts to establish that they were false when issued. The court appeared to rely heavily on the fact that regulators never alleged Fannie Mae violated GAAP or asked the company to restate its financial statements during the class period. Nevertheless, the court allowed claims to proceed based on allegations regarding misrepresentations about the quality of Fannie Mae’s internal controls. The court relied heavily on three internal emails where the Chief Risk Officer warned, among other things, that the company “was not even close to hav[ing] control processes for credit, market and operational risk.” The court also found that these emails inferred scienter because they demonstrated a conscious and reckless disregard to managing the risks associated with subprime loans.

- Citigroup obtained favorable results on motions to dismiss a putative class action alleging that Citigroup and 14 of its officers and directors made misleading statements regarding its risk exposure and overstated the value of its assets, particularly those associated with the subprime mortgage market. In re Citigroup Sec. Litig., — F. Supp. 2d —, No. 07-CV-09901(SHS), 2010 WL 4484650 (S.D.N.Y Nov. 11, 2010). Seven individual defendants were dismissed from the lawsuit; only statements made between February 2007 and April 2008 were held actionable (reducing the class period from five years to a little over one year); and claims regarding disclosures about Citigroup’s involvement with several other financial instruments were dismissed. However, the court allowed plaintiffs’ Section 10(b) claims concerning disclosures made about the extent, nature and value of Citigroup’s collateralized debt obligation (“CDO”) holdings to proceed as to Citigroup and seven of the individual defendants. The court found plaintiffs pleaded sufficient facts to establish a strong inference of scienter because the individual defendants attended meetings where CDO risks were discussed: “Although plaintiffs do not allege the matters discussed at the meetings, their mere existence is indicative of scienter.” Moreover, the court allowed plaintiffs to use the “group pleading doctrine” to allege the individual defendants were responsible for the misleading statements and omissions in Citigroup’s public filings because they were insiders or wielded significant influence.

- In Friedus et al., v. ING Group N.V. et al, — F. Supp. 2d —, 2010 WL 3554097, No. 09-CV-01049 (LAK), 2010 WL 3554097 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 14, 2010) the court dismissed the vast majority of claims asserted by plaintiffs that purchased ING bonds through offerings made in June 2007, September 2007 and June 2008. First, the court held that claims regarding the June 2007 bond offerings were untimely because the September 2007 offering documents contained sufficient “storm warnings” that the value of ING’s Alt-A and subprime mortgage holdings were at risk. Because plaintiffs did not file their initial compliant until 2009, the claims were barred by the one-year limitation period. Second, the court found there was insufficient evidence to find that any disclosures regarding the September 2007 offering were incomplete or inaccurate. The court held that plaintiffs could not simply rely on generalized statements about market turmoil, but instead had to allege that ING’s specific assets had been effected to show that disclosures about the relatively safety of its holdings were misleading. Finally, the court jettisoned many of plaintiffs’ allegations regarding the June 2008 offering. After noting it was a “close call,” however, the court let stand allegations that descriptions of ING’s mortgage-backed assets as “near prime and of high quality” may have been misleading, finding such allegations “sufficiently link the troubles in the market at large to ING’s portfolio to support a plausible inference that ING’s assets in 2008 were ‘extremely risky.'”

- Not all was positive for defendants in 2010, however. On November 18, 2010, the jury in In re BankAtlantic Bancorp, Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 07-CV-61542 (S.D. Fla.), returned a verdict in plaintiffs’ favor, finding the company and two of the five individual defendants made false and misleading statements about the bank’s loan portfolio and exposure to loan losses. The jury awarded damages of $2.41 per share, which could amount to as much as $42 million. The jury apparently rejected BankAtlantic’s loss causation argument, i.e., that the catastrophic meltdown of the Florida real estate market was responsible for plaintiffs’ losses rather than any allegedly misleading statements made by BankAtlantic.

- The court in In re Am. Int’l Group, Inc. 2008 Sec. Litig., — F. Supp. 2d —, No. 08-CV-04772 (LTS), 2010 WL 3768146 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 27, 2010), denied defendants’ motion to dismiss a securities fraud lawsuit alleging that defendants materially misstated the extent to which AIG had accumulated exposure to the subprime mortgage market through its securities lending program and its credit default swap portfolio. In particular, the company’s statements failed to disclose the CDS’ valuation and collateral risk, which would require AIG to quickly come up with collateral for securities that had been devalued or defaulted on, according to plaintiffs. The opinion also contains an interesting standing discussion. The court cited its prior holding in In re Morgan Stanley Mortg. Pass-Through Certificates Litig., No. 09-CV-2137 (LTS), 2010 WL 3239430, at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 17, 2010), that the structure of MBS offerings requires a different standing analysis than may be appropriate in cases involving ordinary corporate debt securities in which the alleged misstatements are found in common shelf registration statements. The court found that the AIG plaintiffs, who sued on Medium Term Notes, did not rely on the information furnished in the prospectus and pricing supplements unique to each of the 101 offerings, but rather on the alleged material misstatements and omissions located in the common elements of the three different registration statements (that is, the Company’s Forms 10-K, 10-Q, and 8-K incorporated therein). The court therefore allowed plaintiffs to sue on all 101 offerings at issue, because purchasers in each of the offerings could trace their injury to the same underlying conduct on the part of the defendants.

- After allowing the class plaintiffs to amend their complaint, the court sustained section 12(a)(2) claims against the Merrill underwriter because plaintiffs specifically alleged they had purchased securities directly from Merrill. Public Employees’ Ret. Sys of Miss. et al. v. Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc, et al., No. 08 Civ. 10841 (JSR), 2010 WL 4903619 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 1, 2010).

- Defer LP v. Raymond James Fin., Inc. et al., No. 08-CV-03449 (LAK), 2010 WL 3452387 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 2, 2010), was the first auction rate securities (“ARS”) case to survive the preliminary motion stage. Although the court dismissed the majority of plaintiffs’ securities fraud claims with prejudice for failure to plead actionable misstatements or scienter, it did allow limited claims to proceed against one Raymond James subsidiary (“RJA”), finding allegations that RJA failed to disclose the liquidity risks of ARS in order to unload its surplus inventory were sufficient to meet the “opportunity and motive” prong of the scienter standard in the Second Circuit. The court stated that “given the deterioration of the market . . . and RJA’s wish to reduce its own position from November 2007 forward, it is quite reasonable to infer that RJA had a motive to conceal the ARS illiquidity risk from customers.” In a potential blow to achieving class certification, however, the court rejected plaintiffs’ argument that the alleged misrepresentations were part of a larger scheme to defraud. Instead, the court found that the only actionable misrepresentation had been made to a single plaintiff by one RJA broker.

- In what appears to be an outlier case, the court in New Jersey Carpenters Health Fund v. Residential Capital, LLC, No 08 CV 8781 (HB) (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 21, 2010), allowed additional plaintiffs to intervene in an effort to cure standing defects caused by the limited purchases of the initial plaintiffs. The court declined to address whether the new plaintiffs’ claims were time-barred, despite recognizing the consensus that the American Pipe tolling doctrine does not apply where the class representatives lacked standing to assert their claims. Emphasizing that the claims for which the named plaintiffs lacked standing were nonetheless pleaded in the complaint and thus defendants were on notice of them, the court deferred a decision on the statute of limitations until the class certification stage.

- Finally, several more credit crisis cases settled in the second half of 2010, but no discernible trend has yet to emerge. On November 9, the court in In re New Century Financial Corp. Sec. Litig., No. CV 07-00931-DDP-FMOx (C.D. Cal.) approved a settlement agreement calling for approximately $65 million to be provided on behalf of the directors and officers, the outside auditor to provide approximately $44.7 million, and the underwriters to provide approximately $15 million to settle the respective claims against them. Gibson Dunn represented New Century’s independent directors. On October 25, 2010, Toll Brothers, Inc. entered into a stipulation of settlement to resolve a subprime-related class action for $25 million. (City of Hialeah Employees’ Ret. Sys. et al. v. Toll Brothers, Inc. et al., No. 07-01513 (E.D. Pa.)). Plaintiffs had alleged that Toll Brothers and its individual officers and directors misrepresented the company’s ability to succeed during the nation’s housing downturn. On December 15, 2010, Ambac Financial Group announced it reached an agreement in principal to settle two subprime-related securities class action lawsuits against the company and its officers and directors (In re Ambac Fin. Group, Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 08-CV-41 (S.D.N.Y.); Tolin et al. v. Ambac Fin. Group, Inc. et al., 08-CV-11241 (S.D.N.Y). The settlement calls for Ambac to pay a total of $27.1 million, of which $24.6 million will be paid by D&O insurers with the company paying the balance. Of the 230 credit-crisis lawsuits filed so far, Toll Brothers and Ambac represent only the sixteenth and seventeenth settlements, approximately. Both settlement agreements require court approval.

Pleading–Scienter

The scienter element of Section 10(b) claims remains a major hurdle for plaintiffs at both the circuit and district court level. We reported on a number of decisions in the first half of the year in our Mid-Year Update. Courts issued the following noteworthy decisions in the second half of 2010.

- The Sixth Circuit recently issued a notable decision concerning scienter in the context of claims against outside auditors. In Louisiana School Employees’ Retirement System v. Ernst & Young, L.L.P., 622 F.3d 471 (6th Cir. 2010), the court upheld the dismissal of a class securities fraud action against Ernst & Young stemming from its audit of Accredo Health, Inc., a pharmaceutical distribution company. The Sixth Circuit reaffirmed that “[t]he standard of recklessness is more stringent when the defendant is an outside auditor.” Id. at 479. Given this strict standard, the Sixth Circuit rejected the plaintiffs’ attempt to premise scienter on Ernst & Young’s use of “old and stale data” from a previous year to test the allowance attributable to the Company’s receivables. Id. at 481. The court found that “even if Ernst & Young should have included the appropriate data in its audit, its failure to do so does not create an inference that it acted with the requisite scienter.” Id. at 482. In addition, the court noted that for “a red flag to create a strong inference of scienter in securities fraud claims against an outside auditor, it must consist of an ‘egregious refusal to see the obvious, or to investigate the doubtful.'” Id. Additionally, the Sixth Circuit followed several district courts in holding that the magnitude of an accounting error does not give rise to an inference of scienter against an auditor, and rejected the plaintiffs’ allegation that accounting improprieties in a prior year’s financial statement gave rise to an inference of scienter in the audit opinion at issue. Id. at 483-484. Further, the court held that the mere receipt of audit fees could not constitute a sufficient motive to indicate scienter. Id. at 484.

- In another case concerning competing scienter inferences, the Second Circuit in an unpublished disposition affirmed the dismissal of Section 10(b) claims arising from a failed merger. First New York Sec., L.L.C. v. United Rentals, Inc., 2010 WL 3393757 (2d. Cir. Aug. 30, 2010). Plaintiffs had purchased United Rentals stock following reports of a contemplated merger, and alleged that “URI acted with scienter by deliberately and improperly concealing the risks affecting the deal in order to stabilize the market price of its stock,” resulting in damage when the deal fell through. Id. at *1. The Second Circuit held that the inference of scienter was not compelling, and that the more plausible inference was that the defendants failed to disclose any risks because they believed “that the deal was going to close.” Id. at *2.

- In an unpublished disposition, the Ninth Circuit affirmed dismissal of Section 10(b) claims against Jones Soda Company because plaintiffs failed to plead facts sufficient to support any inference of fraudulent intent. In re Jones Soda Co. Sec. Litig., 2010 WL 3394274 (9th Cir. Aug. 30, 2010). Plaintiffs asserted that the company and its former CEO “misled investors by overstating their efforts and accomplishments as Jones Soda entered the carbonated, canned soft drink market, leading to an over-valuation of Jones Soda’s stock.” Id. at *1. The Ninth Circuit noted that the plaintiffs attempted to allege scienter from a single fact–sales data defendants received from retailers. Id. at *2. Noting that the complaint did not say “what sorts of data” were covered in the reports, or which retailers the data covered, the court held that “[t]his single factual allegation [was] not sufficient” to create an inference of scienter. Id.

- The Ninth Circuit also provided guidance on the degree to which subjective recklessness is required to establish scienter at summary judgment. In SEC v. Platforms Wireless International Corp., 617 F.3d 1072 (9th Cir. 2010), the court reaffirmed that a showing of subjective recklessness is necessary to prove scienter. Id. at 1093 (citing Gebhart v. SEC, 595 F.3d 1034, 1042 (9th Cir. 2010)). Nevertheless, the court held that “a defendant ordinarily will not be able to defeat summary judgment by the mere denial of subjective knowledge of the risk that a statement could be misleading.” Id. at 1094. “When the defendant is aware of the facts that made the statement misleading, he cannot ignore the facts and plead ignorance of the risk.” Id. In other words, the court held, “if no reasonable person could deny that the statement was materially misleading, a defendant with knowledge of the relevant facts cannot manufacture a genuine issue of material fact merely by denying (or intentionally disregarding) what any reasonable person would have known.” Id. at 1094 (emphasis added). Applying this standard, the Ninth Circuit affirmed summary judgment against the defendants for issuing a press release that claimed a prototype had been built when none existed. Id. at 1096. Specifically, the court rejected the defendants’ argument that the company’s former CEO did not act with scienter when he issued the press release because he did not subjectively believe it was misleading. Id. at 1095. Instead, the Ninth Circuit found that the CEO acted with scienter because he admitted to knowing that no prototype existed when he authorized the press release. Id. Indeed, the court held that defendants’ admission that they knew the underlying facts meant that “no reasonable juror could credit” their assertion that they did not subjectively believe the contrary statement was misleading. If such “a self-serving assertion could be viewed as controlling, there would never be a successful prosecution or claim for fraud.” Id.

- In another notable decision, United States v. Goyal, 2010 WL 5028896, at *1 (9th Cir. Dec. 10, 2010), the Ninth Circuit reversed the conviction of a CFO charged with accounting and securities fraud. The company allegedly used a practice known as “sell-in” accounting, which allowed it to “recognize revenue from . . . deals earlier than it should have and thereby overstated its revenue.” Id. The government charged the CFO with lying to auditors when he represented the company was compliant with GAAP. The Ninth Circuit held, however, that no reasonable jury could have inferred scienter under the facts. First, the court rejected the argument that intent could be inferred from “Goyal’s desire to meet [the company’s] revenue targets, and his knowledge of and participation in deals to help make that happen.” Id. The court held that this was “simply evidence of Goyal doing his job diligently.” Id. Second, the court held that “Goyal’s presumed knowledge of GAAP as a qualified CFO does not make him criminally responsible for his every conceivable mistake.” Id. As the court noted, “[i]f simply understanding accounting rules or optimizing a company’s performance were enough to establish scienter, then any action by a company’s chief financial officer that a juror could conclude in hindsight was false or misleading could subject him to fraud liability without regard to intent to deceive. Id. Third, the court ruled that the linkage of the CFO’s compensation to the company’s success was irrelevant. Id. “Such a general financial incentive merely reinforces Goyal’s preexisting duty to maximize . . . performance, and his seeking to meet expectations cannot be inherently probative of fraud.” Id. Fourth, the court found no facts to support the argument that the CFO “must have known about various revenue recognition problems because others at the company claimed they were aware of accounting improprieties.” Id. at *7. Although Goyal was a criminal case, the court’s discussion of scienter should influence the inferences courts are willing to accept in civil matters as well.

- In Vining v. Oppenheimer Holdings, Inc., 2010 WL 3825722 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 29, 2010), the court dismissed securities fraud claims arising from the purchase of Auction Rate Securities (which are long-term or perpetual instruments that pay interest or dividends at rates set by periodic auctions). The plaintiffs claimed that the defendants failed to disclose material facts about the nature and condition of the ARS market, and in particular that they suggested the market was more liquid than it was before its eventual collapse. Id. at *4. The district court held that plaintiffs failed to adequately plead scienter. Though the plaintiffs claimed Oppenheimer must have known that the market was illiquid and fragile, the court reasoned that the plaintiffs’ own allegations made clear that the ARS market collapse was an unprecedented event, which yielded a competing–and more compelling–inference that the collapse was also unforeseen. Id. at *14. Moreover, the court held that purported red flags in the form of prior ARS illiquidity were limited to a “narrow segment” of the market, and that the most compelling inference was that “executives did not believe the [prior] failures represented a threat to the remainder of the market.” Id. The court emphasized that this “competing inference appears even stronger when considered in light of the lack of specificity that Plaintiffs provide regarding Oppenheimer’s alleged uniform management directives” regarding what statements to make about the ARS market. Id.

- Similarly, in Footbridge Limited Trust v. Countrywide Home Loans, Inc., 2010 WL 3790810, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 28, 2010), the court dismissed claims stemming from mortgage-backed securities, where the plaintiffs alleged “that a ‘corrupt culture’ at Countrywide, combined with defendants’ ‘lust for high yields and high profits’ motivated defendants to make fraudulent misrepresentations to plaintiffs in order to induce them to invest in the Securities.” Id. at *4. Specifically, the plaintiffs claimed that Countrywide “made material misrepresentations and omissions regarding the quality of the underlying loans and, more specifically the underwriting guidelines used in the origination process . . . .” Id. The court found, however, that express warnings in the offering documents about the risks involved in these investments, as well as the flexible nature of the underwriting guidelines, undermined plaintiffs’ claim that the defendants acted with scienter. Id. at *20. The court also emphasized the failure to connect any of the alleged misstatements with loans in the securitizations at issue. Id.

- A court found that plaintiffs adequately pleaded scienter against Fannie Mae for misstatements involving Fannie Mae’s internal risk management and controls. In re Fannie Mae 2008 Sec. Litig., 2010 WL 3825713 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 30, 2010). Plaintiffs alleged that “Fannie did not have the risk and control management infrastructure necessary to properly assess the risks of subprime and Alt-A mortgages, but misinformed the market that they had such safeguards in place.” Id. at *13. The court found that emails written by the Chief Risk Officer “suggest that Fannie was conscious of its internal inability to manage the risks associated with subprime loans. Proceeding headlong into an unfamiliar market and telling investors that risk controls are in place while working . . . without the internal ability to analyze the risks associated with that market is certainly enough . . . to show an inference of scienter and therefore survive a motion to dismiss. Id. at *15.

- Similarly, in In re CIT Group, Inc. Sec. Lit., 2010 WL 2365846 (S.D.N.Y. June 10, 2010), the court found that plaintiffs satisfied the scienter requirement because the complaint alleged particularized facts demonstrating that “Defendants (1) knew about CIT’s lowered lending standards–and, in some cases, affirmatively approved them–while publicly touting the company’s ‘conservative’ and ‘disciplined’ approach to subprime lending; and (2) learned of the deterioration of CIT’s home loan and student loan profiles, while making public statements indicating that CIT was outperforming the market and would suffer only minimal losses.” Id. at *4. Plaintiffs supported these inferences with allegations that “Defendants made written and oral statements indicating that CIT had ‘disciplined lending standards’ and was ‘much more conservative’ than other lenders and that CIT ‘had ‘tightened home lending underwriting, . . . [and] raised minimum FICA requirements.” Id. at *2. As to misstatements concerning the performance of CIT’s student loan portfolio, the plaintiffs offered evidence that the defendants had received Management Process Reports “which included information on the concentration of private, non-guaranteed students loans at Silver State, Silver State’s abnormally high delinquency rate and low graduation rate, and CIT’s failed attempt to the sell the Silver State loan portfolio.” Id. at *3. The court agreed with the plaintiffs and concluded that “[t]he information gleaned from the Management Process Reports, and from monitoring the Silver State portfolio, tended to contradict Defendants’ reassuring statements regarding the student loan portfolio as a whole. Id.

- In In re Rackable Systems, Inc. Securities. Litigation, 2010 WL 3447857 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 27, 2010), the court dismissed a securities fraud class action where plaintiffs alleged that scienter could be inferred from statements made by the company’s former Executive President of Operations during a conference call, in which he admitted that the company should have realized various issues at an earlier time. Id. at *10. The court found that “[t]hese statements do not show that Defendants possessed contemporaneous knowledge” of any facts contradicting an earlier statement, and instead “merely acknowledge[ed] that the company could have been run better in the past.” Id.

- The absence of allegations demonstrating contemporaneous knowledge of falsity was similarly fatal in Zang v. Alliance Financial Services, 2010 WL 3842366 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 27, 2010). There, plaintiff claimed that defendants knew at the time they took his investment that they would foil the financial deals they promised to enter on his behalf, and that they would not return his investment even though they had promised him that it was refundable. Id. at *16. The court found, however, that the complaint “does not allege facts showing the defendants knew when they took money from him that the deals would not be completed and the money would not be returned.” Id. at *17.

Pleading–Confidential Witnesses

In our Mid-Year Update we reported on Campo v. Sears Holding Corp., No. 09-3589-cv, 2010 WL 1292329 (2d Cir. Apr. 6, 2010), in which the Second Circuit ruled a district court was within its discretion to permit depositions of confidential witnesses to aid in resolving a motion to dismiss. Since that time, we are not aware of any courts that have followed Campo and allowed such depositions. One court outside the Second Circuit, however, has refused to follow Campo, and has strongly criticized it. See In re Cell Therapeutics, Inc., No. C10-414MJP, 2010 WL 4791808 (W.D. Wash. Nov. 18, 2010). In rejecting defendants’ request to depose confidential witnesses, that court opined that “the 2nd Circuit’s language favoring the practice is dicta“; no other court has followed Campo; many courts have refused to allow such depositions; and “neither the Federal Rules nor the [PSLRA] supports the practice.” We will continue to follow and report on other courts’ treatment of Campo in 2011.

Courts in the second half of 2010 continued to apply a strict standard to allegations based on confidential witnesses, dismissing complaints for failure to particularly plead facts supporting confidential witnesses’ purported knowledge. See In re NVIDIA Corp. Sec. Litig., No. 08-CV-04260-RS, 2010 WL 4117561 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 19, 2010) (dismissing complaint based on eight confidential witnesses where two “were never employed by NVIDIA, making it unlikely that they have personal knowledge,” and the others were too remotely placed within the company); Local No. 38 IBEW Pension Fund v. American Express Co., No. 09-Civ-3016, 2010 WL 2834226 (S.D.N.Y. July 19, 2010) (rejecting confidential witness allegations that amounted to “anecdotes and conclusory statements of belief” and where many of the confidential witnesses were rank-and-file employees or outside contractors who were not in contact with individual defendants and did not have access to relevant information).

Pleading–Standing

In our Mid-Year Update, we reported on a number of decisions in which courts dismissed cases at the pleading stage for lack of standing. Standing continued to play significant role in the second half of the year, with courts in particular distinguishing between ordinary corporate securities offerings and those involving mortgage-backed securities. See, e.g., Boilermakers National Annuity Trust Fund v. WaMu Mortg. Pass Through Certificates, Series AR1, 2010 WL 3815796 (W.D. Wash. Sept. 28, 2010), Katz v. Gerardi, 2010 WL 3034358 (D. Colo. Aug. 3, 2010), In re Citigroup Inc. Bond Litigation, — F.Supp.2d —, 2010 WL 2772439 (S.D.N.Y. July 12, 2010), Maine State Retirement System v. Countrywide Financial Corp., — F.Supp.2d —, 2010 WL 4452571 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 4, 2010), Hoff v. Popular, Inc., — F.Supp.2d —, 2010 WL 3001710 (D. Puerto Rico Aug. 2, 2010), Local 295/Local 851 IBT Employer Group Pension Trust and Welfare Fund v. Fifth Third Bancorp, — F.Supp.2d —, 2010 WL 3221813 (S.D. Ohio Aug. 10, 2010).

- For example, in Maine State Retirement System, supra, the named plaintiffs sought to represent all purchasers of certificates issued in 427 separate MBS offerings, arguing that they had standing with respect to any offering issued pursuant to a common registration statement, including offerings in which they did not actually purchase securities. The court rejected that argument, emphasizing that each MBS certificate was described in a unique accompanying prospectus. Even where there was a common shelf registration, the plaintiffs’ claims relied on separate disclosures or omissions made in individual prospectuses. 2010 WL 4452571, at *4. Although the court granted leave to amend to reflect only the securities in which plaintiffs actually invested, it suggested that it would evaluate standing at the tranche level, as it required plaintiffs to specify the tranches in which they had invested as well. Id. Gibson Dunn represents the underwriter defendants in this case.

- Similarly, a court in the Southern District of New York dismissed putative class claims involving MBS because the named plaintiffs had not purchased most of the securities at issue. In re Morgan Stanley Mortgage Pass-Through Certificates Litig., 2010 WL 3239430 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 17, 2010). Plaintiffs alleged that shelf registrations common to each offering contained material misstatements and omissions. Id. The court found, however, that the suit relied on allegations associated with individual certificates, such as service and ratings issues, as well as allegedly false disclosures in individual certificate prospectuses. Because of the differences between the different certificates, the court concluded that the plaintiffs lacked standing to pursue claims concerning any certificates other than the ones they purchased. Id.

- In a recent case involving medium-term notes, the same court distinguished In re Morgan Stanley, holding that plaintiffs had standing to raise Securities Act claims on behalf of all note purchasers whose offerings relied on the same allegedly misleading shelf registrations. In re American International Group, Inc. 2008 Securities Litig., 2010 WL 3768146 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 27, 2010). Plaintiffs purchased securities from some of 101 separate offerings that were made pursuant to three shelf registrations, each having incorporated by reference SEC filings allegedly containing material misstatements and omissions. Id. at 21-22. Unlike in Morgan Stanley, where the relevant misstatements and omissions occurred in unique prospectuses, the AIG plaintiffs could “trace the injury of the purchasers in each of the 101 offerings to the same underlying conduct on the part of the defendants.” Id. at 22. The court concluded that plaintiffs could assert claims based on all 101 offerings, including those in which they did not participate.

- Similarly, another court in the Southern District of New York found that plaintiffs had standing to bring Section 11 claims arising from a series of bond offerings that relied on common shelf registrations, but lacked standing to raise claims pursuant to Section 12. In re CitiGroup Bond Litig., — F.Supp.2d —, 2010 WL 2772439, at *14 (S.D.N.Y. July 12, 2010). The court found that “where a plaintiff alleges untrue statements in the shelf registration statement or the documents incorporated therein–as opposed to an alleged untrue statement in a supplemental prospectus unique to a specific offering–then that plaintiff has standing to raise [Section 11] claims on behalf of all purchasers from the shelf.” Id. Plaintiffs lacked standing, however, to bring Section 12 claims–which require a direct purchaser relationship between plaintiff and defendant–because they failed to “identify a particular purchase from a particular defendant pursuant to a particular prospectus that it contends contained a particular false or misleading statement.” Id. at *12.

Loss Causation

In addition to the circuit split regarding whether plaintiffs must establish loss causation to obtain the fraud on the market presumption at the class certification stage, and the recent grant of certiorari by the Supreme Court in the Halliburton case out of the Fifth Circuit, which we discussed above, the federal courts of appeals issued several other loss causation decisions.

- The Third Circuit rejected the “fraud-created-the-market” theory of reliance in Malack v. BDO Seidman, LLP, 617 F.3d 743, 756 (3d Cir. 2010). Because the plaintiff could not establish class-wide reliance based on a valid presumption, he could not establish the predominance requirement of Rule 23(b)(3). Id.

- The Ninth Circuit in In re Oracle Securities Litigation, __ F.3d __, No. 09-16502, 2010 U.S. App. LEXIS 23531 at * 29-30 (9th Cir. Nov. 16, 2010), reaffirmed its decision in Metzler Inv. GMBH v. Corinthian Colleges, Inc., 540 F.3d 1049 (9th Cir. 2008), that loss causation is only established if the market learns of a defendant’s fraudulent act or practice, and a plaintiff suffers a loss as a result of the market’s reaction; it is not enough that the market learns of the “impact” of the alleged fraud. Oracle case is a strong companion to In re Omnicom Group, Inc. Sec. Litig., 597 F.3d 501, 512 (2d Cir. 2010), discussed in our Mid-Year Update, in which the Second Circuit held that a plaintiff must show that new facts were disclosed to the market, not just a recharacterization or someone’s opinion of previously disclosed facts.

- The court in In re Imax Securities Litigation, No. 06 Civ. 6128 (NRB) (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 22, 2010), denied a motion for class certification of Section 10(b) because the lead plaintiff was an in and out trader unable to establish loss causation, as it sold its holdings before any corrective disclosure relating to misstatements on which it could have relied.

- A recent unpublished decision from the Ninth Circuit appears more lenient for plaintiffs, however, as we reported in our Mid-Year Update. In a remarkably short memorandum disposition in In re Apollo Group Inc. Securities Litigation, No. 08-16971 (9th Cir. Mar. 3, 2010), the court reversed the district court’s grant of judgment as a matter of law in favor of Apollo, which had overturned a jury verdict for plaintiffs. Gibson Dunn represents Apollo in the case. The Ninth Circuit’s order stated only that the jury could reasonably have found that analyst reports (that had appeared a significant time after various newspaper articles reporting the same information) were nevertheless “corrective disclosures,” because they provided additional or more authoritative information that deflated Apollo’s stock price. The court did not address Apollo’s argument, which the district court accepted, that the analyst reports could not be “corrective disclosures” because they did not contain any new fraud-revealing information. It remains to be seen whether this more lenient approach will eventually make its way into binding precedent.

Negative Causation

Sections 11(e) and 12 of the 1933 Act provides a defense where a defendant can prove that any damages suffered by the plaintiff was the result of something other than the alleged misstatement. In our Mid-Year Update, we discussed a number of decisions addressing the negative causation defense. The few courts that have examined this defense in the last six months have continued to show reluctance to apply it, at least during pre-trial proceedings.