The following post comes to us from John Pollack and David Rosewater, partners focusing on mergers & acquisitions at Schulte Roth & Zabel LLP. This post is based on the Schulte Roth & Zabel Middle Market PE Buyer/Public Target M&A Deal Study; the full publication, including appendices, is available here.

Overview

We regularly conduct studies on private equity buyer acquisitions of U.S. public companies with equity values greater than $500 million (“large market” deals) to monitor market practice reflected by these high-profile transactions. Recognizing the importance of M&A activity in the $100 million to $500 million target equity value range (“middle market” deals), we are commencing a new deal study that identifies “market practice” involving private equity buyer acquisitions of U.S. public companies in the middle market. We also compare our findings for middle market deals to our findings for large market deals. During the period from January 2010 to June 30, 2012, there were a total of 36 middle market deals and 43 large market deals that met our parameters.

Part One

Key Observations: Market Practice and Trends in the Middle Market

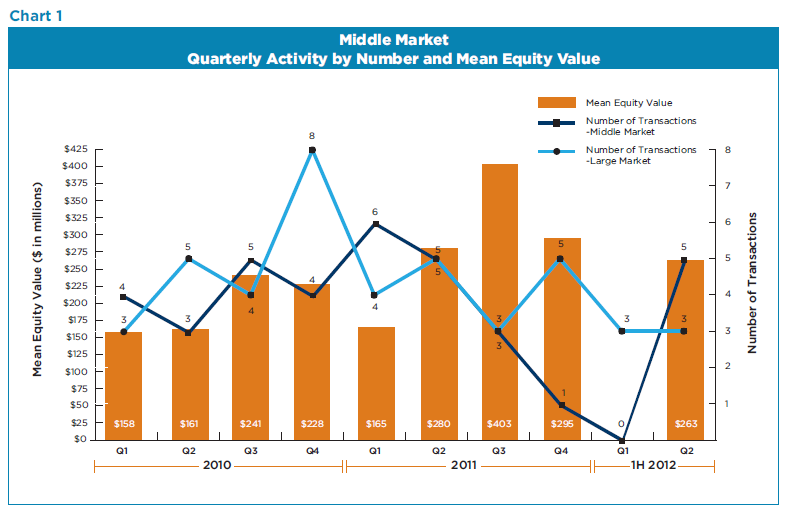

- 1. Activity in the middle market is down year over year. Only 5 deals were signed in 1H 2012 compared to 11 in 1H 2011, a decrease of 55%. Mean equity values of deals in 1H 2012 rose 21% when compared to 1H 2011. The year started with no activity — all of the 1H 2012 deals were signed in the second quarter. (See Chart 1.)

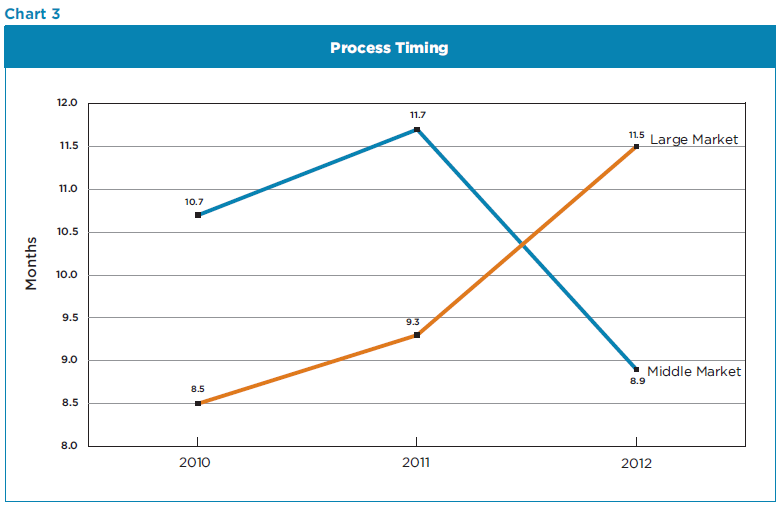

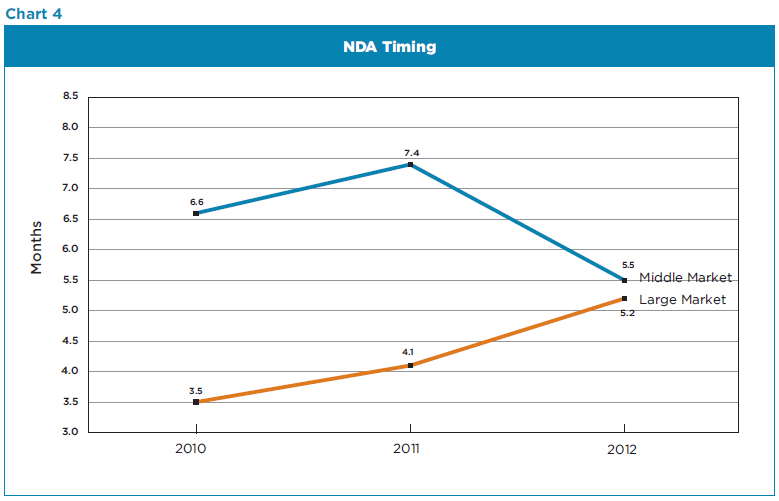

- 2. While fewer deals are getting done, it is taking targets less time to get to signing. In 1H 2012, the mean time from the start of the target’s sale process to the signing of a definitive agreement was 8.9 months compared to 11.7 months for 2011 and 10.7 months for 2010, or approximately 24% faster than 2011. The mean time from the buyer signing a confidentiality agreement to signing a definitive agreement in 1H 2012 was 5.5 months compared to 7.4 months for 2011 and 6.6 months for 2010, or approximately 26% faster than 2011.

- 3. The usage of pre-signing market checks [1] rose in 1H 2012 as compared to 2011, but so did the use of “goshop” provisions. Targets engaged in pre-signing market checks in 40% of the 1H 2012 deals we surveyed as compared to 33% for 2011. Interestingly, while more deals involved pre-signing market checks, more deals also included “go-shop” provisions — 40% of the 1H 2012 middle market deals as compared to 33% for 2011.

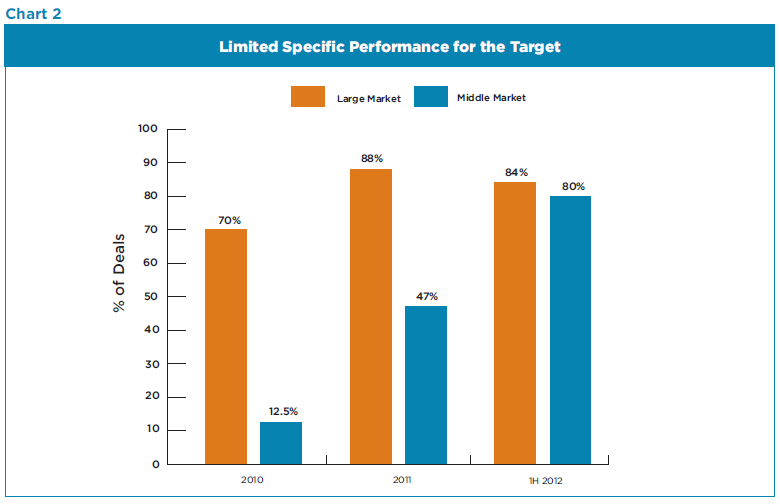

- 4. Since 2010, market practice has changed dramatically on two issues — the target’s right to obtain specific performance to force a buyer to close and use of reverse termination fee (“RTF”). From 2010 to 2011, the number of deals with a limited specific performance right increased significantly (from 12.5% to 47%) and for the 1H 2012 deals, 80% provided for a limited target specific performance right against the buyer (with the remaining 20% providing a full specific performance right). (See Chart 2.) Similarly, from 2010 to 2011, the number of middle market deals where the buyer was obligated to pay a RTF under certain circumstances increased from 50% to 60%, and 100% of 1H 2012 middle market deals included a RTF. Of the 14 deals without an RTF — all pre-dating 2012, none had a financing condition and 13 provided for a full target specific performance right against the buyer. The buyer’s equity commitment in 8 of these 14 deals was for the entire purchase price. The change in market practice on these two issues represents a material change in allocation of risk of deal certainty from buyer to seller.

Part Two

Key Observations: Middle Market vs. Large Market

- 1. In general, market practice is consistent across middle market and large market deals — with a few notable exceptions. Of the key deal terms we analyzed, in general, treatment is the same for both middle market and large market deals. The exceptions are (i) the time it took to sign up deals; (ii) the use of “go-shop” provisions, particularly in deals without a pre-signing market check; and (iii) the size of RTFs payable by buyers. We discuss this differential treatment in greater detail below.

- 2. In 1H 2012, middle market deals were signed up much faster than large market deals. While timing for middle market and large market deals over the 30-month period we surveyed was generally consistent, there was a noticeable difference in 1H 2012. The mean time from start of the target’s process to signing a definitive agreement with the buyer was approximately 9 months for middle market deals and 11.5 months for large market deals. In other words, on average the larger deals took over 25% longer to get signed from the start of the target’s process in 1H 2012. Despite these differences in overall timing, the mean time from buyer signing a confidentiality agreement with the target to signing a definitive agreement in 1H 2012 was consistent for both middle market and large market deals (5.5 months and 5.2 months, respectively). (See Charts 3 and 4.)

- 3. “Go-shop” provisions were used less frequently in middle market deals — in particular, where the target did not conduct a pre-signing market check. Over the 30-month period we surveyed, “go-shop” provisions were included in 42% of the middle market deals and 51% of the large market deals. When we looked at middle market and large market deals that did not include a pre-signing market check, only 48% of the middle market deals included such a provision, whereas 65% of the large market did so. It is difficult to speculate as to why market practice was so different on this issue — it may be that the sensitivity at the board-level regarding satisfying fiduciary duties is greater on large market deals because of a perception that the larger deals attract more attention and therefore have a higher likelihood of shareholder litigation (although research has shown that middle market deals are subject to the same frequency of shareholder litigation as large market deals).

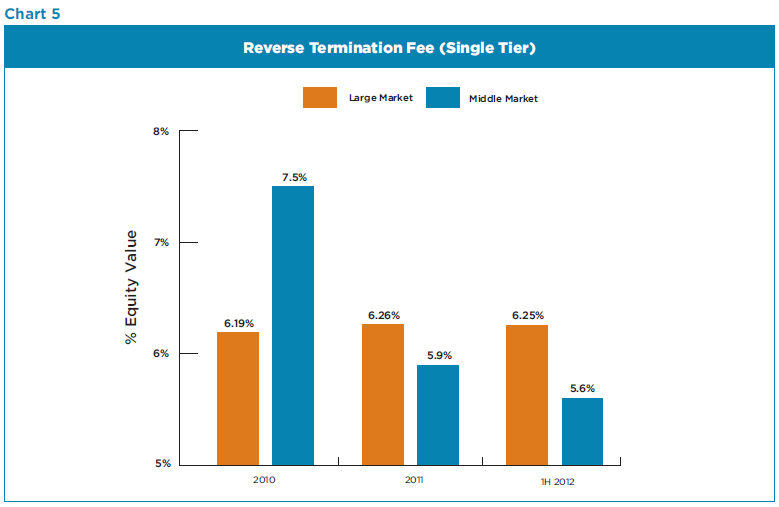

- 4. While RTFs in middle market deals were higher than large market deals in 2010, they have since fallen below those of large market deals. In 2010, the mean size of RTFs (as a percentage of the target’s equity value) in middle market deals decreased from a high of 7.5% in 2010 to 5.6% in 1H 2012, whereas the mean size of RTFs for large market deals slightly increased from 6.19% to 6.25% over the same period. As the use of RTFs in middle market deals has increased as described above, the size of RTFs has decreased. (See Chart 5.)

Survey Methodology

In this deal study, we reviewed selected deal terms of private equity buyer/public company target all-cash merger transactions involving consideration of $100 million to $500 million in enterprise value. We compared treatment of such deal terms in the 16 middle market deals entered into in 2010, 15 transactions entered into in 2011 and 5 transactions entered into in the first half of 2012, as well as the 43 large market deals entered into over the same time period.

Please note that our findings described in this survey are not intended to be an exhaustive review of all transaction terms in the surveyed transactions — instead, we report only on those matters that we believe would be most interesting to the deal community. Our observations are based on a review of publicly available information for the surveyed transactions, which accounted for only a portion of M&A activity during the survey period and may not be representative of the broader M&A market.

Endnote

[1] For purposes of this deal study, we characterized a deal as involving a “pre-signing market check” if the “background of the merger” discussion in the applicable proxy statement or Schedule 14D-9 disclosed that (i) the target solicited interest from at least 25 possible bidders pursuant to an active process prior to execution of the applicable merger agreement; (ii) the target was in discussion with 5 or more possible bidders without engaging in a broader solicitation of interest; or (iii) the target issued a public announcement to the effect that it was exploring “strategic alternatives.”

(go back)

Print

Print