Matteo Tonello is managing director of corporate leadership at The Conference Board. This post relates to an issue of The Conference Board’s Director Notes series authored by Ryan Krause, Kimberly A. Whitler, and Matthew Semadeni.

With recent legislation mandating that publicly traded corporations submit CEO compensation for a nonbinding shareholder vote, a systematic understanding of how shareholders vote under such circumstances has never been so important. Using simulated say-on-pay votes, this post investigates how different levels of CEO pay and company performance can interact to influence how shareholders vote.

In July of 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which, among other things, mandated that all publicly traded U.S. corporations solicit a non-binding advisory vote from their shareholders to approve or reject the compensation of the most highly compensated executives, commonly referred to as “say-on-pay” (SOP) votes. In the short time since the passage of Dodd-Frank, these votes have already made waves. In 2011, the shareholders of Stanley Black and Decker issued a “no” vote, and the board subsequently lowered the CEO’s pay by 63 percent, raised the minimum officer stock requirements, altered its severance agreements to be less CEO friendly, and ended the practice of staggered board terms. [1]

In 2012, Vikram Pandit was forced out as CEO of Citigroup just six months after shareholders rejected an increase in his compensation. [2] As these examples illustrate, SOP “no” votes can require a significant investment of board and firm resources to address shareholder concerns. It would make sense, then, that boards would prefer to avoid “no” votes whenever possible. Knowing this, we set out to understand what factors drive shareholders to vote against their CEO’s compensation.

As discussed in detail below, we conducted two experiments simulating say-on-pay votes. The results suggest that investors value shareholder return over CEO pay. As long as company performance was above average, shareholders supported CEO pay regardless of whether it was high or low.

However, when the company underperformed relative to the market, then shareholders considered CEO pay, voting “no” under circumstances when CEO pay was high and company performance was low. The findings suggest that when the probability of a “no” vote is high (when the recommended CEO pay is high and the firm is underperforming), the board should either reconsider the recommended pay or take steps to mitigate a no vote by educating shareholders on the rationale behind the CEO’s pay.

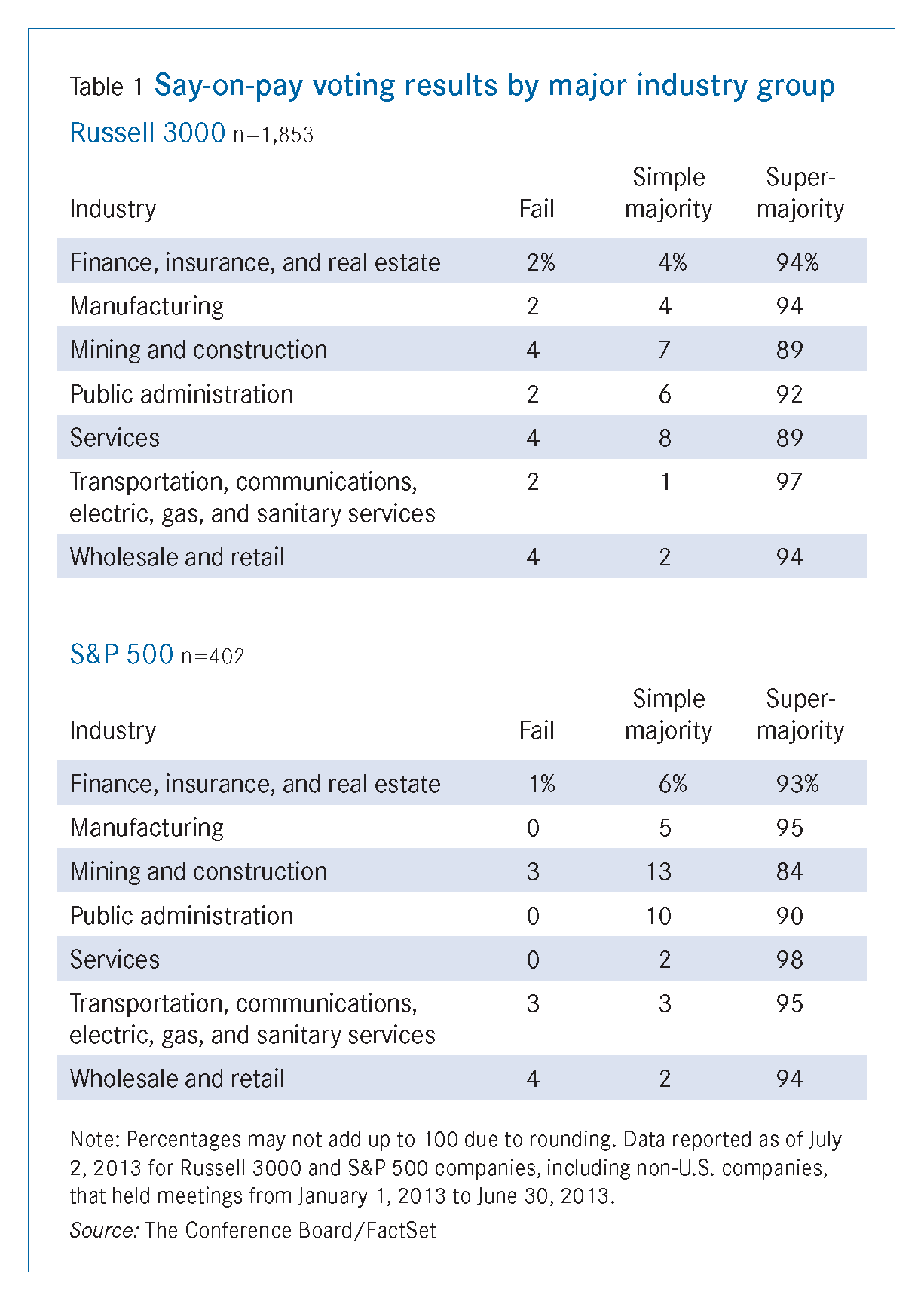

An examination of failed SOP votes by Georgeson Securities found that companies with failed votes underperformed their peers in total shareholder returns (TSR). [3] We examined the results of SOP votes for Russell 3000 and S&P 500 firms that occurred during the first half of 2013. [4] While the votes are often divided into two classes—“pass” or “fail”—we examined three groups: failed votes, votes that passed with a simple majority (greater than 50 percent, but less than 67 percent), and votes that passed with a supermajority (greater than 67 percent). Our rationale for this breakout is that while there are relatively few failed votes, ballots that fail to garner a two-thirds majority are an indication of potential problems, especially since more than 90 percent of the votes analyzed passed with a supermajority. Table 1 shows the three categories broken down by major industry group. The data demonstrate that there is a great deal of heterogeneity among the industries in terms of vote breakout, with some industries (e.g., transportation, communications, electric, gas, and sanitary services) garnering overwhelming supermajorities, and other industries, such as services, not faring well.

We further examined the vote results by analyzing company size (measured in assets), return on assets (ROA), and return on equity (ROE), comparing companies that garnered a supermajority to those that either failed their SOP vote or received only a simple majority. [5] Our results uncovered some important findings. First, for both the Russell 3000 and the S&P 500, companies that failed to receive support were smaller (in terms of assets) than both those that received a simple majority and those that received a supermajority. Companies that received a simple majority were smaller than those that received a supermajority. Turning to ROA and ROE, significant differences exist between companies that received a supermajority and those that did not, but there are no significant differences between companies that failed the vote and those that received a simple majority. This suggests that, as the Georgeson Report found, performance does factor into the outcomes of SOP votes.

But why was SOP mandated? The stated intent of the legislation that was the basis for the Dodd-Frank say-on-pay mandate was to “to prioritize the long-term health of firms and their shareholders.” [6] The hope was that by giving shareholders a voice in compensation decisions, boards would be persuaded to keep CEO pay at “reasonable” levels. But what elicits shareholder opposition to the decision of their elected monitors in the form of a no vote? One condition that might produce a reaction is high CEO pay (i.e., significantly higher than the average Fortune 500 CEO compensation), which, across the board, might be seen as unfair and therefore rejected by shareholders. Conversely, low firm performance (significantly lower than the S&P 500 average shareholder return) may provoke shareholders to register their displeasure with regard to CEO pay. Decades of research in finance and management suggest that shareholders should theoretically be concerned with a strong pay-performance link. [7]

This approach demands symmetry between pay and performance, with high pay linked to high performance (i.e., significantly above the S&P 500 average shareholder return) and low pay (i.e., significantly lower than the average Fortune 500 CEO compensation) linked to low performance. Theoretically, shareholders should vote in favor of a CEO’s compensation as long as it matches firm performance. We would expect to see shareholders voice displeasure when pay and performance are misaligned, such as when pay is higher or lower than company performance.

While academic theory would suggest that all shareholders want is a strong connection between pay and performance, such as high (low) CEO pay coinciding with high (low) company performance, there is a problem with this logic. [8] All the hype and rhetoric that prompted and fueled passage of Dodd-Frank focused on “excessive” CEO pay. Shareholders expressed outrage that the CEOs of companies they deemed “underperforming” were receiving large payouts. Few if any investors complained about CEOs who were underpaid, for whom CEO pay was below average while company performance was above average. SOP votes are frequently discussed in the context of reducing overall CEO pay rather than strengthening the pay-performance link.

Our study was designed to determine whether, as theory suggests, shareholders care about these two outcomes equally, or whether investors focus specifically on CEO pay, company performance, or the misalignment between pay and performance differentially. Stated differently, when shareholders actually vote, do they consider information related to CEO pay and company performance equally? Further, does the shareholder’s “gain” position, where the shareholder is advantaged by the CEO receiving low rewards but providing strong performance discomfort the shareholder the same as the loss position, where the CEO receives high rewards while delivering poor performance as academic theory would suggest? What matters to shareholders as they determine their up or down CEO pay vote?

To answer this question, we conducted two experiments. The reason for using experiments rather than existing data on SOP votes is that it allows us to isolate and manipulate performance and pay conditions and actually determine whether a causal relationship is present. In other words, with a few notable exceptions, the SOP votes to date provide relatively little variance with regard to pay level and firm performance. By using an experimental design, we were able to completely control all the circumstances surrounding the SOP vote, enabling us to determine a clear cause and effect relationship, which is often difficult to do when using secondary data. We conducted both experiments with samples of MBA students at a Top 20 MBA program. Most were shareholders with an average of five or more years of work experience.

For both experiments, we presented subjects with a SOP ballot from a fictional company. The ballot was modeled after the one used in 2010 by Aflac, which was one of the first companies to offer shareholders a SOP vote before it was mandated. [9] Participants were informed that they were to act as shareholders of the fictional company. For the first experiment, we created two pay conditions and two performance conditions. For the pay conditions, we set high pay as a 20 percent increase in pay and low pay as a 20 percent decrease. For the performance conditions, we set high performance as 20 percent above the S&P 500 average of 15 percent (35 percent) and low performance as 20 percent below the same average (-5 percent). Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the four resulting conditions: high pay with high performance, high ay with low performance, low pay with high performance, or low pay with low performance. After reading the SOP ballot, participants were asked to vote on whether or not to approve the CEO’s compensation.

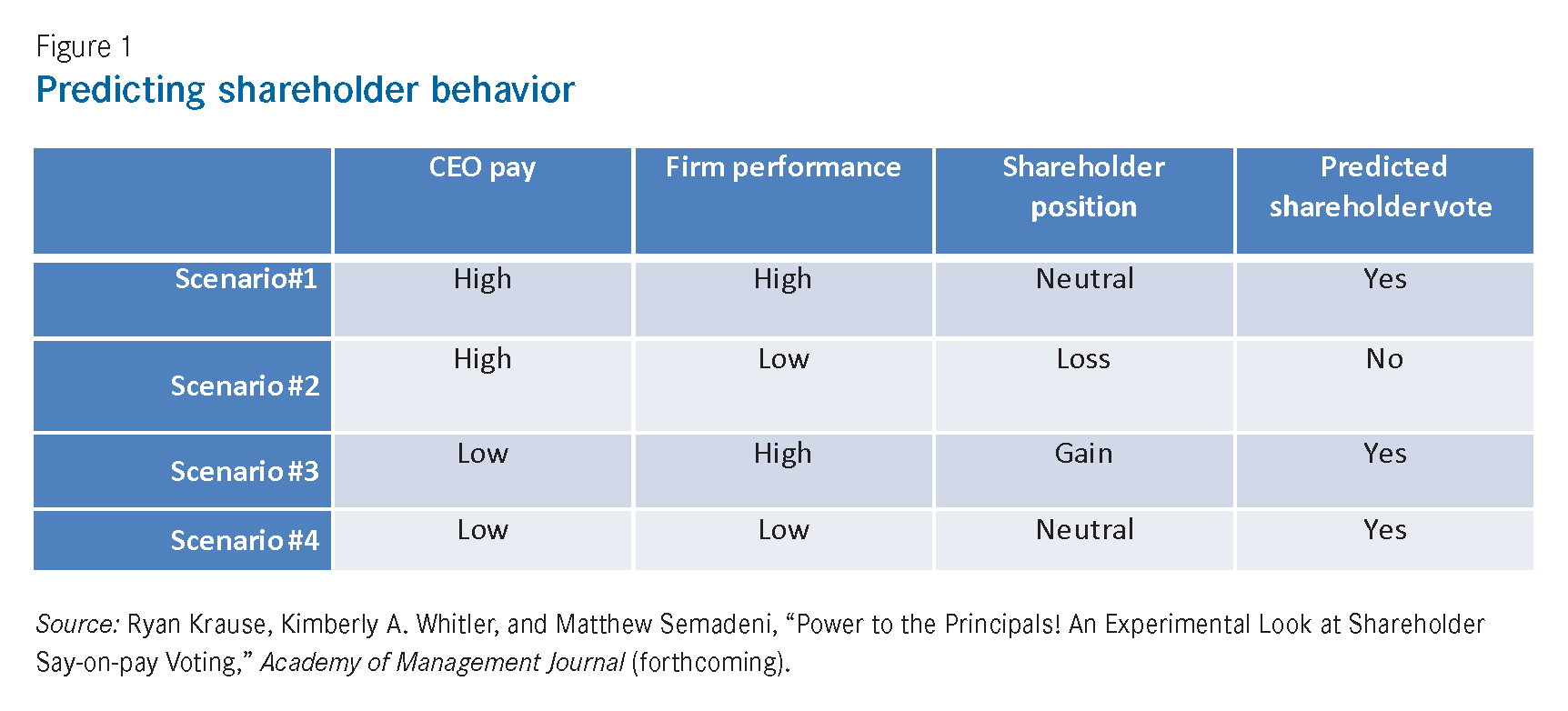

This experiment produced some surprising results. First, “shareholders” overall were no more likely to reject high CEO pay than low CEO pay. This was somewhat unexpected, as recent public ire over high CEO pay led us to believe that a substantial increase in CEO compensation would meet strong resistance. Accounting for company performance, however, illuminated what was going on. The participants in our study were significantly more likely to reject high CEO pay relative to low CEO pay only if company performance was poor (see Figure 1). This is perhaps not that surprising, but what is surprising is that CEO pay exhibited absolutely no effect when firm performance was strong. Shareholders made no distinction between a CEO pay increase and a CEO pay decrease if the firm was performing well. Consistent with our earlier intuition, the results of this study seem to suggest that shareholders are concerned only with CEOs who are deemed to be overpaid, and not with those who appear to be underpaid.

In the first study, to assess shareholder behavior as a general phenomenon, we informed participants only that they were to act as shareholders of the fictional company. While individual shareholder behaviors are of interest, more than 70 percent of shares in the largest 1,000 domestic companies are held by institutional shareholders, making them of interest as well. [10]

To examine institutional investor behaviors, we conducted a second experiment where participants were asked to act as institutional investors with company stock representing 15 percent of their fund’s portfolio. They were also told that their vote would significantly affect the vote outcome due to their fund’s considerable stake in the company. The conditions for the second experiment mirrored those of the first in terms of company performance, but pay was set at the 95th percentile or the 5th percentile of Fortune 500 CEO pay. We changed the pay condition to assess whether the dollar amount of pay would influence shareholders’ actions differently than a percentage increase or decrease. The results of the second experiment confirmed those of the first experiment: shareholders only cared about high CEO pay if they lost money. In other words, investors make voting decisions based first on the performance of the company. When performance is good, investors don’t care about CEO pay. It’s only when company performance is poor that shareholders consider CEO pay and voice their displeasure with a “no” vote when CEO pay is misaligned with company performance (high CEO pay and low company performance).

Our results provide clear evidence that shareholders, even those acting in the role of institutional shareholders, only weigh their own losses when deciding whether to approve a SOP ballot. The findings indicate that underpayment was not of concern to the shareholders. While it can be argued that it is not the shareholder’s role to reject CEO pay when it is low relative to performance, the failure to do so can have important implications for companies. For example, if the company is under-rewarding the CEO relative to the performance delivered, the CEO may leave to seek better opportunities elsewhere. In addition, since pay for the rest of the management team is generally anchored to the CEO’s compensation, and if s/he receives low rewards for strong performance, the rest of the management team may likely be in the same situation, potentially leading to a loss of top talent by the company.

The experiments also clearly showed that raising CEO pay during periods of poor company performance is problematic. While not surprising, the implication is that shareholders do not care about the level of pay as much as they care about the link between pay and performance. This will affect a company where the CEO is hired by the board at a low salary (perhaps as a signal of virtue) and the board later seeks to raise the CEO’s pay. Unless performance is strong, the shareholders may take a dim view of a salary increase without a performance increase. As previously indicated, underpayment of the CEO, even when the company has strong performance, does not appear to be a shareholder concern.

While the results of the study are instructive, what remains unclear is whether a “no” vote is a repudiation of the CEO or of the members of the board of directors (specifically, the compensation committee members). In other words, when a SOP vote fails, are shareholders registering their displeasure with the CEO or with the board members? Though a CEO may be unpopular, s/he does not have authority to set their own compensation and, post-Sarbanes Oxley and Dodd-Frank, should have limited ability to manipulate it. Therefore, a failed SOP vote should be interpreted as a clear signal to the compensation committee members that shareholders disagree with the committee’s assessment of the pay-performance relationship. Further, while boards typically have a data-based rationale for CEO compensation, a failed SOP vote suggests that the board didn’t do enough to educate and win shareholder support for their rationale regarding CEO compensation.

An intriguing consequence of a failed SOP vote is that, while shareholders may be attempting to signal their displeasure with the CEO or the compensation committee, the failure may have repercussions well beyond CEO compensation. A SOP vote failure usually draws negative press for the company that may potentially damage its image. In addition, failed votes can distract both management and the board from focusing on delivering future performance. Third, a failed SOP vote may signal to other top managers that there are limited compensation opportunities moving forward, causing them to seek opportunities elsewhere. Finally, a failed vote on CEO pay may actually affect the pay of all of the top management team.

Predicting—and Managing—Shareholder Voting Behavior

Given the evidence from our experiments presented in Figure 1, we encourage boards, and specifically compensation committees, to actively manage the SOP vote process, particularly if the board plans to increase CEO rewards following a period of poor performance. For instance, the board may seek to provide prospective incentives such as stock options or grants to the CEO if the company is embarking on risky change, such as a turnaround strategy. Boards may also seek to increase pay despite poor performance where a CEO has been underpaid and the increase would represent an adjustment to industry norms. This was the case at Citigroup, and as discussed previously, the board’s decision to raise Vikram Pandit’s pay was rebuked by shareholders. A third potential scenario where the board may seek to raise pay amid poor performance is when the board has hired a high-profile CEO from outside to turn around the company and the pay-performance relationship is not aligned because the initial high compensation required to get the celebrity CEO is misaligned with the company’s poor performance. Under this scenario, the expectation is that the high-profile CEO has been brought in to turn the company around, which takes time to achieve. In the short-term, CEO pay will be high relative to company performance. While there are justifications for cases of high pay coupled with low performance, our research suggests that boards must manage the SOP vote process if they hope to minimize the likelihood of a failed vote. Our results show that, when given basic information about pay and performance and limited justification for the misalignment, shareholders are more likely to vote against the executive pay packages.

Given this information about shareholder voting behavior, boards and companies can take steps to reduce the likelihood of a shareholder “no” vote. Our research assumed that only the required information (proxy statement) was provided to shareholders. Boards typically have a solid rationale for their CEO pay recommendations, but, if this is not communicated to shareholders, investors will not have this information. Explaining the rationale behind CEO pay may make it more palatable to investors. Furthermore, boards could be more transparent about the requirements to achieve bonus targets and could report actual CEO performance against those targets on the back end. To the extent that CEO pay is justified and the rationale is communicated effectively to investors prior to a say-on-pay vote, there is an increased chance of shareholders supporting the board’s recommendation.

Endnotes:

[1] Gretchen Morgenson, “When Shareholders Make Their Voices Heard,” New York Times, April 7, 2012 (www.nytimes.com/2012/04/08/business/say-on-pay-votes-make-more-shareholder-voices-heard.html?pagewanted=all).

(go back)

[2] Suzanne Japner, Joann S. Lublin, and Robin Sidel, “Citigroup Investors Reject Pay Plan,” Wall Street Journal, April 17, 2012 (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304299304577349931225459386.html).

(go back)

[3] “Facts Behind 2013 Failed Say on Pay Votes,” Georgeson Report, June 11, 2013 (www.computershare-na.com/sharedweb/georgeson/georgeson_report/GeorgesonReport_061113.pdf#1).

(go back)

[4] Data reported as of July 2, 2013, provided by The Conference Board/Fact Set Research Systems.

(go back)

[5] ROA, ROE and assets were taken from company annual reports for FY 2012.

(go back)

[6] Martin Lipton, Jay W. Lorsch, and Theodore N. Mirvis, “Schumer’s Shareholder Bill Misses the Mark,” Wall Street Journal, May 12, 2009 (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124208536180008385.html).

(go back)

[7] See Michael C. Jensen and William H. Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics, 3, no. 4, pp. 305–360; Bengt Holstrom, “Moral Hazard in Teams,” Bell Journal of Economics, 13, no. 2, pp. 324–340; James D. Westphal and Edward J. Zajac, “The Symbolic Management or Stockholders: Corporate Governance Reforms and Shareholder Reactions,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 42 no. 1, pp. 127–153; and Catherine M. Daily, Dan R. Dalton, and Albert A. Cannella Jr., “Corporate Governance: Decades of Dialogue and Data,” Academy of Management Review, 28, no. 3, pp. 371–382.

(go back)

[8] Michael C. Jensen and Kevin J. Murphy, “Performance Pay and Top-Management Incentives,” Journal of Political Economy, 92, no. 2, pp. 225-264.

(go back)

[9] Claudia H. Deutsch, “Aflac Investors Get a Say on Executive Pay, a First for a Publicly Traded U.S. Company,” New York Times, May 6, 2008 (www.nytimes.com/2008/05/06/business/06pay.html?_r=0).

(go back)

[10] Matteo Tonello and Stephen Rabimov, The 2010 Institutional Investment Report: Trends in Asset Allocation and Portfolio Composition, The Conference Board, Research Report 1468, November 2010.

(go back)

Print

Print