Matteo Tonello is managing director of corporate leadership at The Conference Board. This post relates to an issue of The Conference Board’s Director Notes series authored by Richard Lee and Jason D. Schloetzer, both of Georgetown University. The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here. Recent work from the Program on Corporate Governance about hedge fund activism includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon P. Brav, and Wei Jiang.

Activist hedge funds merit the attention of corporate directors, as the value of the assets under management increases and activist funds’ targets expand well beyond small capitalization companies. This post reviews the tactics used by two prominent activist hedge fund managers to create change in 13 companies in their portfolio and highlights four perceived governance failures at target companies that attracted activist funds’ attention. This post also includes a review of characteristics of activist hedge funds, the incentives their managers have to generate positive returns, and current research investigating whether and how hedge fund activism affects target companies.

The value of assets managed by activist hedge funds has increased dramatically in recent years. A study by eVestment documents a seven-fold increase in the assets managed by such funds from $23 billion in 2002 to an estimated $166 billion in early 2014. The momentum continues, with total new capital inflows into activist funds reaching $6 billion in the first quarter of 2014, which represents approximately 30 percent of all inflows into event driven funds. According to eVestment, activism continues to be among the best-performing primary fund strategies, posting returns of nearly 10 percent since October 2013 and 18 percent for the year. The number of shareholder activist events has also increased—from 97 events in 2001 to 219 events in 2012. Those trends have led some observers to characterize activist hedge funds as the “new sheriffs of the boardroom.” By 2013, an estimated 100 hedge funds had adopted activist tactics as part of their investment strategies.

As such, it is increasingly important for directors to become knowledgeable of the tactics activists use to advance investor arguments for changes in target companies. In particular, and as recommended by The Conference Board and its Expert Committee on Shareholder Activism, directors should consider maintaining detailed profiles of hedge funds with material investments in the company’s securities.

This post adds to the store of knowledge available on how this class of hedge funds operates by focusing on the tactics deployed by two prominent figures in the activist world: Carl Icahn of Icahn Enterprises and William “Bill” Ackman of Pershing Square Capital Management. The discussion is particularly timely because Icahn and Ackman have recently agreed to end their prolonged feud, with Ackman suggesting that “[t]here is a much greater possibility that we are on the same side than the opposite.”

Hedge Fund Activism, in a Nutshell

A few words on hedge funds

While there is no generally agreed-upon definition of a hedge fund (a Securities and Exchange Commission roundtable discussion on hedge funds considered 14 different definitions) hedge funds are usually identified by four characteristics:

- they are pooled, privately organized investment vehicles;

- they are administered by professional investment managers with performance-based compensation and significant investments in the fund;

- they cater to a small number of sophisticated investors and are not generally readily available to the retail investment market; and

- they mostly operate outside of securities regulation and registration requirements.

The typical hedge fund is a partnership entity managed by a general partner; the investors are limited partners who have little or no say in the hedge fund’s business. Hedge fund managers have strong incentives to generate positive returns because their pay depends primarily on performance. A typical hedge fund charges its investors a fixed annual fee of 2 percent of its assets plus a 20 percent performance fee based on the fund’s annual return. Although managers of other institutions can be awarded bonus compensation based in part on their performance, their incentives tend to be more muted because they capture a much smaller percentage of any returns and the Investment Company Act of 1940 limits performance fees.

Unlike mutual funds, which are generally required by law to hold diversified portfolios and sell securities within one day to satisfy investor redemptions, hedge funds are not subject to diversification and prudent investment requirements. Hedge funds can also allocate large portions of their capital to a few target companies, and they may require that investors “lock-up” their funds for a period of two years or longer. Moreover, because hedge funds do not fall under the Investment Company Act regulation, they are permitted to trade on margin and engage in derivatives trading, strategies that are not available to institutions such as mutual and pension funds. As a result, hedge funds have greater flexibility in trading than other institutions.

Hedge funds also differ from pension funds and many other institutional investors because they are generally not subject to heightened fiduciary standards, such as those embodied in ERISA. Another difference is that, unlike pension funds, hedge funds are not subject to state or local influence or political control. The majority of hedge fund investors tend to be wealthy individuals and large institutions, and hedge funds typically raise capital through private offerings that are not subject to extensive disclosure requirements. Although hedge fund managers are bound by antifraud provisions, funds are not otherwise subject to more extensive regulation. Finally, hedge fund managers typically suffer fewer conflicts of interest than managers at other institutions. For example, unlike mutual funds that are affiliated with large financial institutions, hedge funds do not sell products to the companies whose shares they hold.

Hedge fund managers have powerful and independent incentives to generate positive returns. Although many private equity or venture capital funds also have these characteristics, they are distinguished from hedge funds because of their focus on particular private capital markets. Private equity investors typically target private companies or going private transactions, and they acquire larger percentage ownership stakes than activist hedge funds. Venture capital investors typically target private companies exclusively, with a view to selling the company, merging, or going public, which means they invest at much earlier stages than both private equity and activist hedge funds. Nevertheless, the lines between these investors are often blurred, particularly between some private equity firms and activist hedge funds that pursue multiple strategies.

Trends in hedge fund activism

Hedge funds may adopt activist tactics as part of their investment strategies, and there has been a significant increase in the value of assets managed by such funds. Studies document a seven-fold increase in the assets managed by such funds from 2002 ($23 billion) to early 2014 ($166 billion) in activist fund assets under management (AUM), with total new investments by the top 10 activist funds reaching $30 billion in 2013. The rising AUM and increasingly bold activism have contributed to the business press identifying activist hedge funds as the “new sheriffs of the boardroom.”

One particularly important channel through which activist hedge funds implement their strategies is by requesting that a certain matter be put to a vote at the target company’s annual shareholder meeting. In 2013, hedge funds submitted 24 shareholder proposals (3 percent of all shareholder proposals), up from 20 proposals in 2012 but below the 33 proposals filed in 2009.Hedge funds waged the majority of proxy contests in 2013, accounting for 24 of the 35 contests at Russell 3000 companies. They have consistently been the most active dissident type, constituting the largest percentage of contests waged (69 percent of the total in Russell 3000 in 2013, up from 39 percent in 2009). Most important, they were highly likely to succeed in these contests, winning or earning partial victories in 19 of the 24 contests waged.

Targets of hedge fund activism

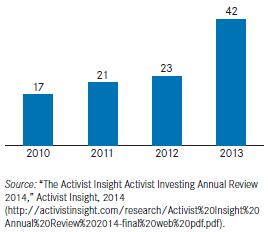

There are a limited number of systematic studies of hedge fund activism, but those that are available provide important insights, both on hedge-fund tactics and their effects on the target company. Hedge-fund activists tend to target companies with low market value relative to book value, although target companies are profitable with consistent operating cash f lows and positive return on assets. Dividend payout at target companies before an activist intervention is generally lower than that at comparable companies. Target companies also have more takeover defenses and pay their CEOs considerably more than comparable companies. Historically, relatively few targeted companies are large-cap companies, which is not surprising given the comparatively high cost of amassing a meaningful stake in such a target. Targets exhibit significantly higher institutional ownership and trading liquidity, making it somewhat easier for activists to acquire a significant stake quickly. However, as activism evolves into an investment class of its own and attracts more and more capital, the characteristics of their target companies may be changing: in 2013, for the first time, almost one-third of shareholder activism took place in companies with market capitalizations of more than $2 billion. In addition, only 23 companies targeted by activist investors were larger than $10 billion in 2012; by 2013, that number jumped to 42 companies.

Does activism generate value?

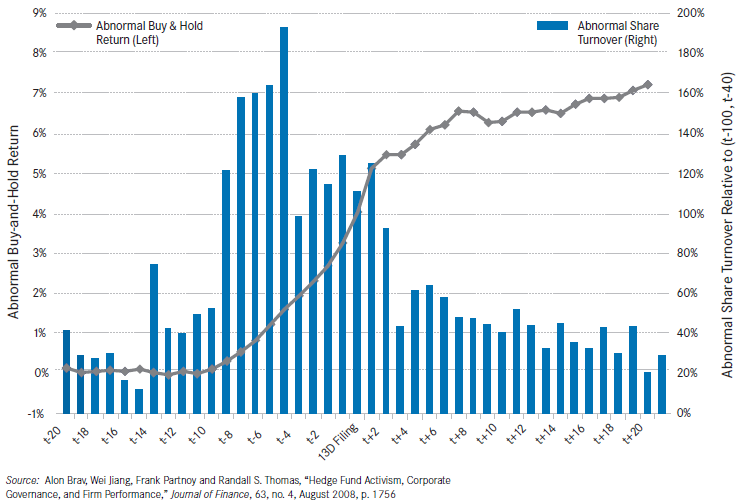

There is substantial debate about the extent to which activist events affect target company value. A study by Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, Randall S. Thomas, and Frank Partnoy documents a 7 percent abnormal stock return around the filing of a Schedule 13D (an indication of an activist fund’s investment in a target company), suggesting that market participants view hedge fund activism as value creating. Most important, the same study finds that the favorable effect on stock price does not reverse within the following year. According to these findings, it appears that promising returns depend on what the activists demand. Activism that targets the sale of the company or changes in business strategy, such as refocusing and spinning-off noncore assets, is associated with the largest positive abnormal partial effects. In contrast, there is little evidence of a favorable market reaction to capital structure-related activism—including debt restructuring, recapitalization, dividends, and share repurchases— or to governance-related activism—including attempts to rescind takeover defenses, oust CEOs, enhance board independence, and curtail CEO compensation.

Chart 1. Number of large-cap companies targeted by activist investors (2010–2013)

Chart 2. Buy-and-hold abnormal return around the filing of Schedule 13Ds

The solid line (left axis) plots the average buy-and-hold return around the Schedule 13D filing, in excess of the buy-and-hold return of the value weighted market, from 20 days prior the 13D file date to 20 days afterwards. The bars (right axis) plot the increase (in percentage points) in the share trading turnover during the same time window compared to the average turnover rate during the preceding (-100, -40) event window.

A separate but related study by Robin Greenwood and Michael Schor argues that the documented increase in stock returns is largely concentrated among activist interventions that involve a subsequent takeover, suggesting there is little relation between hedge fund activism and returns when a takeover is not part of the activist strategy. Aside from equity performance, other investigations reveal that activist interventions by hedge funds are associated with improvements in the operating performance of the target company, changes in corporate governance, lower CEO compensation, higher sensitivity of CEO turnover to company performance, and higher rates of director turnover.

Activist tactics

While activists generally propose a wide variety of changes to targeted companies, approximately 45 percent seek changes in corporate governance and the remaining 55 percent pursue non-board-related proposals. In 2013, the 24 shareholder proposals submitted by activist hedge funds were mostly concentrated on asset divestiture, capital distributions, the election of dissidents’ director nominees, and the removal of board members. Hedge funds led the majority of contests seeking board representation last year, representing 14 proxy contests out of the 22 motivated by the election of a dissident’s nominee(s) to the board of directors.

The following discussion provides detailed insights into the tactics used by two prominent activist hedge fund managers—Carl Icahn of Icahn Enterprises and Bill Ackman of Pershing Square Capital Management—to effect change in 13 target companies from 2002 through 2014. The review highlights four perceived corporate governance failures at target companies that attract the attention of activist funds.

Specifically, hedge fund activism is more likely when an entrenched board fails to:

- establish a clear corporate strategy;

- replace a CEO in a timely manner, impeding the execution of the corporate strategy;

- seek alternative uses for the company’s valuable noncore assets (for example, through divestiture) or fails to maximize shareholder value when taking the company private;

- distribute “sufficient” levels of cash to shareholders through dividend payouts and share repurchase programs.

In addition to these perceived governance failures, the analysis of Ackman’s hostile interaction at Herbalife, Inc. and Allergan provide timely examples of potential emerging trends in hedge fund activism: the use of derivative instruments to target companies with a perceived overvaluation of equity given the company’s economic fundamentals (Herbalife) and combining efforts with a public company to launch a hostile takeover bid of another public company (Allergan).

The Activism of Icahn Enterprises

Carl Icahn is chairman of Icahn Enterprises, a diversified holding company which trades on the NASDAQ and has a market capitalization of $12 billion.

Icahn recently stated that “[t]here are lots of good CEOs in this country, but the management in many companies leaves a lot to be desired. What we do is bring accountability to these underperforming CEOs when we get elected to the boards.” Icahn’s statement highlights one of his main activist strategies: identifying companies with perceived managerial deficiencies and attempting to gain a board seat(s) to discipline boards that fail to remove poorly performing managers.

The case studies reinforce his image as an activist investor who buys large stakes in companies he believes to be undervalued and then seeks to change the business. The studies reveal that Icahn’s primary activist tactic is to identify boards whose directors are unable to deftly navigate fundamental issues with corporate strategy, perhaps due to a failed acquisition (Yahoo!) or multiple strategic setbacks (Netflix, Dell). In addition, Icahn targets boards whose directors do not adequately identify profitable uses of the company’s assets, whether the assets are patent portfolios (Motorola), cash reserves (Apple), or a division (eBay). His recent effort at eBay to target the corporate governance practices of a Silicon Valley company is new and might signal an emerging trend in hedge fund activism.

Icahn actively uses various media channels to advance his agenda. He frequently issues open letters to the shareholders of his targets, appears on television, and makes statements via social media and his Shareholders’ Square Table website. As a result, corporate boards should have an integrated, cross-platform response to the various types of public messages that activist fund managers may employ to reach a diverse shareholder base and communicate their message to market participants in general.

Motorola (2007-2011)

Tactics: Proxy contest to gain board representation; public statements and letter to shareholders; access to company records; threat of litigation

Outcome: Spin off and sale of company for a 63 percent premium over closing price

On January 30, 2007, Icahn revealed that he had accumulated 33.5 million shares of Motorola, representing 1.4 percent of the company prior to its split into Motorola Mobility and Motorola Solutions. Icahn met with Motorola CEO Ed Zander to discuss Icahn’s proposal for the company to buyback $12 billion in company stock. Motorola was struggling as sales of the KRZR mobile phone were below expectations. By April 2007, Icahn had launched a proxy contest to gain a seat on the board. He faulted Motorola’s directors as a “passive and reactive board, which failed to timely steer management in the right direction.” However, on May 7, 2007, the preliminary results of a shareholder vote revealed that the activist had failed to win a seat on the board, despite increasing his ownership stake to 2.9 percent.

In 2008, Icahn changed his tactics. On March 24, he announced that he was suing Motorola to be granted access to documents related to its mobile device business that would be critical for assessing whether the board of directors had failed to protect Motorola’s shareholders. In a heated letter to shareholders, he nominated his own candidates for the board and said, “It is essential to the future of Motorola that its directors realize that the BOARD, especially at this precarious time, is NOT A COUNTRY CLUB OR A FRATERNITY, and that truly ‘qualified’ people whose interests are truly aligned with stockholders are needed on the board in order to save Motorola.” By that time, Icahn had further increased his stake in Motorola to 6.3 percent (or 142 million shares). Two days later, the board gave in to the pressure resulting from Icahn’s public campaign and announced that Motorola would split into two entities, a mobile phone unit and a set-top box and communications equipment unit. By April 8, 2008, Motorola had agreed to appoint two of Icahn’s nominees to the board in exchange for the dismissal of his litigation against the company.

Icahn continued to increase his Motorola holdings, and he owned 10.4 percent (247.1 million shares) by August 2010.After a delay due to the economic crisis, Motorola finally split into Motorola Mobility and Motorola Solutions on January 3, 2011.On August 15, 2011, Google announced that it would buy Motorola Mobility for $12.5 billion, representing a 63 percent premium over its previous closing price. The acquisition was spurred in part by Icahn who, in July of that year, had encouraged Motorola to sell its lucrative portfolio of mobile phone patents.

Yahoo! Inc. (2008-2010)

Tactics: Proxy contest to gain board representation or control

Outcome: $320 million loss in two years; Icahn and two directors appointed to board; failed CEO succession; exited position

In May 2008, Icahn purchased 50 million shares of Yahoo and launched a proxy contest to gain control of its board of directors. Yahoo was losing ground to Google and Microsoft in the core search market, and there was growing disappointment with Yahoo’s management team, which nixed Microsoft’s offer to buy the company for a 35 percent premium. Icahn stepped up his rhetoric and accused CEO and cofounder Jerry Yang and the Yahoo board of being entrenched and unwilling to truly consider an acquisition offer. By August 2008, Yahoo’s board agreed to provide Icahn a board seat and expand the board to 11 directors, allowing Icahn to appoint two directors himself. Icahn sought to replace Yang, who had assumed the CEO post at the board’s request in June 2007.

Yang relinquished the CEO position in November 2008, and Carol Bartz became chief executive three months later. Upon her appointment, Bartz was praised for her technology sector experience and her status as an outsider who could bring a fresh perspective to both the board and the company’s strategy. While Icahn was critical of Yang, and he and his two affiliated directors were Yahoo board members when Bartz was appointed as CEO, the extent of Icahn’s involvement in selecting Bartz is unclear.

Bartz’s tenure was controversial, and she was terminated, reportedly by phone, in early September 2009.In October 2009, Icahn resigned from the board and his departure was reported to be on amicable terms. When he resigned, Icahn stated that it was no longer “necessary at this time to have an activist on the board.” From October 2009 through May 2010, Icahn slowly exited his position. He reportedly lost an estimated $320 million on his investment.

Netflix (2012-present)

Tactics: Public statement on value resulting from sale of the company

Outcome: $825 million earnings in 14 months, despite limited or no action against company; reduced position

On October 31, 2012, Icahn disclosed a 9.98 percent stake in Netflix. Icahn accumulated his position at a time when Netflix was reeling from a failed attempt to raise consumer-subscription prices and split the company into two separate businesses while simultaneously implementing a cash-draining effort to expand overseas and develop original content. Icahn used the announcement of the strategy redirection as an opportunity to tell shareholders that the company would have “significant strategic value” if it were acquired by a larger company. On November 5, 2012, the board of directors adopted a shareholder rights plan that would come into effect if any investor acquired more than 10 percent of the company.

Between November 2012 and October 2013, Netflix continued to execute its strategy of growing international markets and developing original content. During this time, there were no public statements from Icahn about his interactions with Netflix management. While it is conceivable that private interactions did occur, it appears that Icahn supported the company’s management team during the strategic transition, with an Icahn associate stating that the company’s management team was “exceedingly competent.” In October 2013, Icahn reduced his holdings to 4.5 percent, earning $825 million on his Netflix investment in only 14 months.

Although Icahn’s original intent at time the he acquired his position appeared to be to press management to sell the company quickly, it seems that his appreciation for the company’s strategy and confidence in the management team led him to maintain a more passive role in the company’s transformation.

Dell Inc. (2013)

Tactics: Effort to gain board representation or control; public statements on undervaluation resulting from taking the company private via letters to shareholders, media interviews, and social media

Outcome: Estimated $200 million earnings in seven months; failed effort to gain board representation or control; exited position

In February 2013, Michael Dell and Silver Lake Partners sought to take Dell private for $13.65 per share. This price valued the company at $24.4 billion, representing a 37 percent premium over the average share price at that time. Michael Dell sought to take the company private to enable him to transform the company free from public scrutiny from a maker of personal computers into a provider of enterprise computing services. However, several large shareholders, including Southeastern Asset Management and T. Rowe Price, opposed the deal, believing that Dell’s bid undervalued the company. Icahn entered the fray in March 2013, announcing that he had accumulated a 9 percent stake in the company. He began a lengthy and public campaign against Michael Dell and the company’s board to either prevent Dell from going private or to force Michael Dell and Silver Lake to increase their bid.

Icahn used a series of letters to shareholders, combined with relatively newer tactics via media interviews and social media, to communicate with Dell’s shareholders and market participants in general. He called Dell’s board entrenched and pushed for Michael Dell to be fired and for the entire board to be replaced. Using rather extreme language, Icahn even appealed for shareholders to consider “What is the difference between Dell and a dictatorship?”

Icahn also used legal action against the company. He tried to get the courts to force Dell to hold its shareholder meeting at the same time as the special vote on the decision to go private, thereby giving Icahn a chance to propose a slate of directors to replace the current board. However, in August 2013, a judge refused to fast track this lawsuit, which stopped Icahn’s legal efforts on that front. In a separate effort, Icahn encouraged Dell shareholders to exercise their right to an appraisal of the transaction, which would allow shareholders to demand a court hearing on the value of their holdings, a process that would likely have taken months to navigate the court system.

By July 2013, Michael Dell and the board had restructured their proposal by increasing their bid to $13.75 per share plus a one-time dividend of $0.13 per share. Using their own legal moves, Dell’s board was able to change the company’s voting rules to ignore shareholder abstentions instead of counting them as “no” votes, and to change the record date for stockholders to determine eligibility to vote on the proposed takeover, limiting the rights of shareholders who purchased their shares recently. Icahn also revealed that his unnamed CEO-in-waiting backed out at the last minute.

In the end, these setbacks prompted Icahn to end his opposition to Michael Dell’s bid in September 2013, writing that “The Dell board, like so many boards in this country, reminds me of Clark Gable’s last words in Gone with the Wind, they simply ‘don’t give a damn.’”

Apple Co. (2013-present)

Tactics: Public statements on need for company to distribute cash to shareholders

Outcome: More aggressive share buyback plan; maintains position

In April 2013, Apple bowed to Wall Street pressure and said it would return $100 billion to shareholders by the end of 2015, double the amount previously set aside. The cash distributions would include a $60 billion stock repurchase program.

By August 2013, Icahn began to accumulate a position in Apple, and he started to push for the company to complete a $150 billion buyback by taking advantage of low interest rates to borrow funds, a move that Icahn argued could push the company’s share price back to the $700 level it reached briefly in September 2012. The following month, he met with Apple CEO Tim Cook to discuss the potential for a large share buyback program.

In January 2014, Icahn purchased an additional $500 million of the company’s shares, raising his total ownership stake to $3.6 billion. On February 10, 2014, Icahn announced that he was backing down from his nonbinding proposal to force the company to return cash to shareholders due to opposition by proxy advisory firm ISS and the company’s announcement of a more aggressive share buyback plan.

While not entirely successful, Icahn’s actions did appear to affect the company’s capital return program. In April 2014, the company increased its share repurchase authorization to $90 billion from the $60 billion announced in 2013. The company also increased its quarterly dividend by 8 percent and said it will split its stock seven-for-one in June 2014.

In addition, the company announced that it would boost the overall size of its capital return program to more than $130 billion by the end of 2015, up from its previous $100 billion plan. To demonstrate his use of social media, Icahn tweeted that he “agree[s] completely” with Apple’s plans to boost its buyback plan.

eBay Inc. (2014-present)

Tactics: Public statements via letters to shareholders, media interviews, and social media on need for company to revamp corporate governance practices and to spin off a division; effort to gain board representation or control

Outcome: One mutually agreed-upon independent director added to board; failed attempt to spin off division; maintains position

In January 2014, Icahn disclosed that he had taken a nearly 2 percent stake in eBay, nominated two candidates to eBay’s board of directors, and submitted a proposal to spin-off eBay’s PayPal business. Icahn stated that he was prepared for a proxy contest, if necessary.

On February 24, Icahn released an open letter to eBay shareholders, stating that eBay’s lapses in corporate governance were the “most blatant we have ever seen.” In particular, Icahn believed there were conflicts of interest among its board. Icahn highlighted eBay director Marc Andreessen, who has investments in seven startups that compete with eBay’s PayPal unit and was part of an investor group that acquired a controlling interest in Skype from eBay in 2009. Icahn questioned Andreessen’s knowledge of the Skype deal and what information was withheld from eBay shareholders. In addition, Icahn claimed that eBay director Scott Cook has material conflicts of interest; Cook is the founder of Intuit, a PayPal competitor.

eBay’s board responded to Icahn’s claims, citing Icahn’s “mudslinging attacks.” Icahn subsequently released eight additional open letters to eBay shareholders from late February to early March. Icahn was, “growing a bit tired of reading eBay’s repetitive evasive responses” and stated that he was “demanding an inspection of eBay’s relevant books and records pursuant to his right as a stockholder under Delaware corporate law.” eBay’s board replied by stating that Icahn should “stick to the facts” and challenged him to an “honest, accurate debate.” In his fifth open letter to eBay shareholders, Icahn escalated his criticism by accusing eBay CEO John Donahoe for “inexcusable incompetence” over the Skype deal, costing shareholders over $4 billion. eBay retaliated by rejecting Icahn’s nominees for its board and renominating all current directors up for reelection, including Andreessen and Cook. In addition to publishing open letters on his Shareholders’ Square Table website, Icahn used other forms of media including twitter and TV appearances.

On April 10, 2014, Icahn and eBay agreed to settle their months-long debate after Icahn failed to garner support for a spin-off of eBay’s PayPal unit from the company’s major shareholders. Under the agreement, Icahn withdrew his two nominees for board seats and his demands for a PayPal spin-off, while eBay added an additional, mutually agreed-upon independent director, David Dorman.

The Activism of Pershing Square

William “Bill” Ackman is CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management, which, according to a Form 13F filed December 31, 2013, has $8.23 billion in assets under management.

Ackman has a reputation as a brazen activist investor who buys large stakes in companies he believes are undervalued. The case studies—notably, his joint hostile takeover effort with Valeant Pharmaceuticals at Allergan—reinforce that image and highlight several differences between his activist approach and that of Icahn.

In particular, Ackman’s primary tactic appears to be his hands-on efforts to completely transform a company, often through substantial changes in both board representation and top management, as evidenced by his actions at J.C. Penney, Canadian Pacific Railways, and Air Products and Chemicals. Similar to Icahn, Ackman targets boards he feels have not adequately identified profitable uses of the company’s assets, such as his efforts at Target to revamp the company’s credit card holdings and real estate assets.

In contrast to Icahn, Ackman is perhaps best known for his high-profile campaigns to bring down his target companies through detailed and often overwhelming arguments designed to move a target’s share price. The MBIA and Herbalife cases demonstrate how Ackman targets companies that he believes are overvalued given their current economic fundamentals, and the extreme measures he will take to make the case against the target company’s valuation. His heavily publicized presentations, often held with little advance notice, highlight the need for boards of directors to have the ability to quickly respond to such an attack.

MBIA (2002-2008)

Tactics: Public statements and presentations challenging the company’s credit rating

Outcome: Over $1 billion earnings in six years; exited position

In 2002, Ackman’s first hedge fund, Gotham Partners, began to scrutinize MBIA, challenging the company’s AAA credit rating. Ackman released a lengthy report titled, “Is MBIA Triple A?” that criticized MBIA as too highly leveraged to hold a AAA credit rating, citing the firm’s high outstanding guarantee liabilities and a heavy use of off-balance sheet vehicles for fund-raising purposes.

Ackman’s bets against MBIA eventually paid off in 2007, when reports surfaced of potential trouble resulting from MBIA’s guarantee of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). As of March 31, 2007, MBIA had insured $5.4 billion in subprime mortgage-backed securities, which reportedly presented “negligible” risk because the insurer generally insured higher-rated classes of mortgage-backed securities. MBIA, however, had increased its exposure to CDOs. MBIA disclosed that, as of the end of 2006, $2.4 billion of the $7.7 billion in mortgage CDOs it had insured were backed by subprime mortgages.

As the economy began to falter in 2007, Ackman released a presentation provocatively titled “Who’s Holding the Bag?” that contended MBIA had guarantees on some $5 billion worth of potentially low-quality securitizations of subprime-mortgages and other types of asset-backed debt that could ultimately damage the company’s balance sheet. By October 2007, MBIA’s shares had dropped 40 percent on rising concerns that losses from the mortgage-related securities the company insured would deplete the capital reserve required to maintain its AAA credit rating. Ackman profited handsomely from his position in MBIA as the company’s business eroded during the financial crisis, contributing to his returns of nearly 26 percent during a period of economic instability and significant market losses.

Target Corp. (2007-2011)

Tactics: Proxy contest to gain board representation or control; public statements on need for company to spin off a division and sell non-core assets

Outcome: Partially successful sale of noncore assets; failed proxy contest; exited position

In April 2007, Ackman began to accumulate a position in Target Corp., establishing a special fund to invest in the company that eventually held a 9.97 percent stake through a combination of options and stock purchases. Ackman had made further bets on the company through options and derivatives called total return swaps. Although these total return swaps did not confer voting power, Ackman claimed that the swaps brought his total economic exposure to 12.6 percent of Target’s shares.

Ackman argued that Target could unlock shareholder value through the sale of its credit card business and the reduction of its real estate holdings. Target was one of the few retailers that still managed its own credit card operations, while Ackman noted that similar retailers had sold their portfolios. In September 2007, under pressure from Ackman, Target announced it was exploring strategic options for its credit card portfolio. In March 2008, the company said it engaged in talks to divest 50 percent of its credit portfolio for approximately $4 billion. In May 2008, the company announced the sale of an undivided interest that represented 47 percent of its credit card portfolio for $3.6 billion. Target said the proceeds would fund store expansion, debt repayment, and share repurchases.

In October 2008, Ackman pushed for a second strategic change at the company—the creation of a separate company that would own the land on which its stores are located, aimed at unlocking the value of a real estate portfolio with an estimated value of $40 billion. However, Ackman quickly backed down from this proposal and pushed instead for the company to spin off its real estate assets via a real estate investment trust (REIT) with only 20 percent of the land under its stores, instead of the 100 percent he originally suggested only one month earlier. Ackman, who claimed that an IPO of the new REIT would raise about $5.1 billion, said he would invest $250 million in the new company.

Ackman’s vision for the company’s real estate assets proved untenable. In November, 2008, the company publically rejected his proposal to create a real estate investment trust, saying the potential value it would create was “highly speculative.” The investment fund that held Ackman’s position in Target fell 40 percent in the month of January 2009 alone. By February 2009, Ackman had reduced his position in the company to 7.8 percent. Undeterred, Ackman entered into a prolonged proxy contest in an attempt to gain five board seats, including one for himself. Ackman lost the proxy contest with 70 percent of votes cast in favor of management’s proposed board. He estimated that his hedge fund had spent more than $10 million on the failed proxy fight. After this failed attempt to gain control of the board and convert company-owned property into a real-estate investment trust, Ackman continued to draw down his Target position to 4.4 percent by August 2009. By 2011, Ackman had closed his position in Target.

J.C. Penney (2010-2013)

Tactics: Appointed to board; public statements calling for the resignation of the CEO and board chairman

Outcome: $712 million losses in 23 months; resigned from the board; failed CEO succession; exited position

In October 2010, Ackman began to accumulate a position in J.C. Penney for approximately $25 per share. Steven Roth of Vornado Realty Trust also started to accumulate a position, and Ackman/Roth eventually held 26 percent of outstanding shares. Ackman joined the company’s board in February 2011 and promptly pressed for the replacement of the sitting CEO Myron Ullman. On June 14, 2011, the company’s board announced that Ackman’s preferred CEO candidate, Ron Johnson, would replace Ullman as CEO. At the time, Johnson was senior vice president of retail operations of Apple. He assumed the role of CEO in November 2011.

Following Ackman’s plan for transforming J.C. Penney, Johnson revealed a strategy to reinvent the company by converting its department stores into smaller boutiques and eliminating coupon discounts. However, the transformation was not an immediate success, and the strategy required significant cash outflows to remodel stores. By February 2013, Johnson admitted that his turnaround effort was not working as planned, and J.C. Penney reported a much larger than expected fourth-quarter loss. The strategic shift not only alienated existing customers but it also failed to attract new customers. Revenues declined as much as 25 percent during Johnson’s tenure. In early April 2013, the company’s board announced Ron Johnson’s departure and reinstated Myron Ullman as CEO.

In August 2013, a public dispute arose between Ackman and the other directors over the company’s leadership. In a letter sent to fellow directors that was publicly disclosed, Ackman called for the departures of Ullman and the company’s chairman of the board. The board responded in an August 8 letter, stating, “The company has made significant progress since Myron E. (Mike) Ullman III returned as CEO four months ago, under unusually difficult circumstances. Since then, Mike has led significant actions to correct the errors of previous management and to return the company to sustainable, profitable growth.” In the letter, the company’s chairman called Ackman’s actions “disruptive and counterproductive.”

On August 12, 2013, Ackman resigned from the board. By August 27, he had sold his entire stake in the company (some 39 million shares) to Citigroup for $12.90 per share. In total, Ackman lost approximately $712 million on his stock ownership and swaps tied to the company’s share price.

Canadian Pacific Railway (2011-present)

Tactics: Proxy contest to gain board representation or control

Outcome: Successful proxy contest; board control; successful CEO succession; reduced position after 300 percent increase in share price

In late 2011, Ackman acquired a 14 percent stake in Canadian Pacific Railway, making Pershing Square Capital Management the company’s largest shareholder. Ackman quickly pushed for changes to transform the company, including the ouster of its CEO. When the board rejected his plan, Ackman launched a proxy contest and received overwhelming support from shareholders. Hours before the company’s annual meeting in 2012, CEO Fred Green and four other directors resigned, giving Ackman a major victory.

Ackman’s victory was soon tested, as the Teamsters Canada Rail Conference, a union that represented some 4,800 Canadian Pacific rail workers, began a week-long strike shortly after Ackman won his drawn-out proxy battle. The strike was due in part to stalled union contract talks that started in October 2011, and Ackman’s involvement in the company became the tipping point. In particular, union employees were concerned about possible cuts to pension funding by an estimated 40 percent; the issue of work rules was also highly contentious.

By early July 2012, E. Hunter Harrison, Ackman’s pick for the company’s new CEO and a railroad veteran, began to implement a turnaround strategy. Within days, Harrison replaced most of Green’s senior management team with his contacts from Canadian National Railway Corporation. Harrison and his new management team boosted the company’s operating performance to record levels of operating efficiency. Harrison also achieved his original three-year plan within two years, which sent share prices up 300 percent, a result that prompted Ackman to sell one-third of his holdings in late 2013.

However, the company’s longer-term outlook is unclear. Harrison has cut a net 4,800 jobs (from a total of 19,500 when he took over as CEO) and initiated disciplinary actions against employees that reportedly caused many to resign. His actions have revived an image of a “culture of fear and discipline” similar to that during his tenure at Canadian National. Prominent union organizers have publicly criticized his cost-cutting strategy contending that it will leave his hand-picked successor, Keith Creel, who is slated to take the reigns as CEO in 2016, with a hostile workforce and a management team that “lacks experience and independent thought.” Ackman’s actions after Harrison’s departure remain to be seen.

Air Products and Chemicals (2013-present)

Tactics: Public statements regarding “ideas on how to add value”

Outcome: Ongoing; maintains position

In July 2013, Ackman circulated a letter to his investors seeking up to $1 billion for a new investment fund that would target a single company, quickly stirring speculation about the target company’s identity. On July 31, 2013, Ackman announced he had acquired a 9.8 percent stake in Air Products, a producer of industrial gases. This investment, valued at $2.2 billion, represented Ackman’s largest investment at that time.

Ackman stated publically that his company had “some ideas on how to add value.” Pershing Square indicated that it intended to engage in talks with the company’s board, top management, and other major shareholders about the company’s current management and its strategic plans. The firm also announced it might pursue a proxy solicitation.

The company’s board, noting unusual trading in the company’s shares a week prior to Ackman’s announcement, adopted a shareholder rights plan to foil any potential takeover attempts. Shortly after Ackman announced his stake, he reportedly had a phone call with the company’s sitting CEO, John McGlade, to discuss the situation. Several meetings followed, and Ackman presented his proposal to improve shareholder value to the board in late August 2013, which included a search for a new CEO.

Within one month, the company announced that McGlade would depart the company in 2014 and that the board would appoint three new independent directors—two directors proposed by Ackman and one mutually agreed-upon nominee. However, by the end of April 2014, roughly seven months after announcing McGlade’s departure, the company had yet to name a new CEO, increasing concern among Wall Street analysts about the lack of an heir apparent.

Herbalife Ltd.: A Confluence of Activist Conflict (2012-present)

Tactics: Public statements and presentations challenging that the company’s business model; stirred investigations of the company by multiple US regulatory agencies; attempts to motivate investigations by foreign governments

Outcome: Ongoing; restructured position due to $500 million loss in 10 months

There is perhaps no better example of the public tumult that activists can cause than the ongoing interventions at Herbalife Ltd., a nutrition and weight management company.

In December 2012, Ackman disclosed that he had taken a $1 billion short position in Herbalife. His detailed, lengthy, and widely publicized presentation titled, “Who Wants to be a Millionaire?” portrayed the company as a pyramid scheme that lacked any true retail customers. Herbalife shares declined nearly 40 percent following Ackman’s statements.

Ackman’s presentation, however, did not persuade all investors. In January 2013, Icahn and Ackman engaged in a heated televised debate regarding Herbalife’s business prospects. Other hedge funds disclosed that they accumulated significant positions in Herbalife: George Soros’s Soros Fund Management disclosed a 4.9 percent stake, Icahn accumulated a 16.5 percent stake, and Dan Loeb’s Third Point reported an 8.2 percent stake (Third Point has since exited its position.) In addition, Bill Stiritz disclosed a 6.5 percent stake as of late 2013.Stiritz stated his intention to advise Herbalife’s board on “potential strategies for confronting the speculative short position that currently exists in the company’s stock and its attendant negative publicity campaign.”

On October 29, 2013, Ackman, with momentum building against him, sent a 52-page letter to PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Herbalife’s auditor. The letter warned that “PwC may incur substantial liabilities in the event of the company’s failure.” In response, an Herbalife spokeswoman told CNBC, “As Mr. Ackman continues to lose his investors’ money on a reckless $1 billion bet against Herbalife, he has become increasingly desperate.” At least part of this statement was true, as, by October 2013, Ackman had lost an estimated $500 million on his position.

On November 22, 2013, Ackman renewed pressure on the company with a new 62-slide presentation at the Robin Hood Investors Conference that questioned where Herbalife was getting all of its sales and offered to pay for the collection and audit by an independent company of all retail data from Herbalife’s distributors. Ackman claimed that the company targeted vulnerable, low-income minorities. In an interview with Bloomberg, Ackman stated that he would take his efforts against Herbalife to “the end of the earth.”

On December 16, 2013, Herbalife announced the completion of PwC’s review of the company’s financial statements, which failed to identify any significant issues. In response, Ackman circulated a letter to his investors on December 23 that said he would release further information in 2014 about the company’s violations of multi-level market restrictions in China. He stated, “Herbalife is not an accounting fraud; it is a business opportunity fraud that relies on deception.”

An investigation by the New York Times showed the “unprecedented” scale and depth of Ackman’s behind-the-scene efforts to bring down Herbalife. Ackman’s team used a wide reaching lobbying and public image strategy that included organizing protests, setting up news conferences, orchestrating letter writing campaigns, and lobbying members of Congress. His team also paid over $130,000 to civil rights organizations, notably several large Latino organizations, to support his message or collect names of victims. This has not been without controversy, as several of the supposed victims did not recall writing letters to complain about Herbalife and there are instances of letters being nearly identical. There is also evidence of ties between Ackman and several members of Congress. The support of congressmen and congresswomen will be instrumental in pushing regulators to investigate Herbalife, a catalyst that could drive the stock price down significantly. Meanwhile, Herbalife has not been idle; they have hired an entire lobby team, including the Glover Park Group and the Podesta Group, to counter Ackman’s lobby. They have also increased donations to various organizations to neutralize Ackman’s payments.

On January 23, 2014, Senator Edward Markey of Massachusetts filed letters with Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission requesting that the agencies investigate Herbalife as a possible pyramid scheme. Markey also sent a letter to the company’s CEO Michael Johnson that questioned the company’s compensation and sales data. To support his request for an investigation, he cited a single instance in which a Massachusetts family reportedly lost $130,000 by investing in Herbalife. The company’s shares declined more than 10 percent on the day Senator Markey’s letters were filed.

On March 11, 2014, Pershing Square presented the results of an independent investigation it funded into Herbalife’s business practices in China. Pershing Square alleged that Herbalife violated China’s direct selling and pyramid sales laws. Legal experts in China say that the laws are unclear, making it a “regulatory grey area.” In addition, even though “the law in China says one thing, if it’s actually enforced is a completely different thing.” Thus, many do not expect regulators to take strong action against China.

However, on March 12, 2014, Herbalife disclosed that the US Federal Trade Commission was initiating an investigation into the company. Herbalife management indicated that the company “welcomes the inquiry given the tremendous amount of misinformation in the marketplace … We are confident that Herbalife is in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.” On April 11, 2014, the Financial Times reported that that the US attorney’s office in Manhattan and the FBI were investigating Herbalife. Before news of the criminal probe was reported, Herbalife’s shares were down just over 2 percent, and ended the day 14 percent lower at $51.48.On April 17, 2014, the Illinois Attorney General joined the fight, announcing its own investigation into Herbalife. Ackman’s campaign highlights a relatively unique strategy of leveraging political pressure against a company’s business practices. Whether or not Ackman will succeed has yet to be determined, but it is clear that he will go to “the end of the earth” in his tactics against Herbalife.

Allergan (2014-current)

Tactics: Partnered with corporate acquirer to pursue a joint bid for a public company

Outcome: Ongoing

In March and April 2014, Ackman began accumulating a position in Allergan, the maker of Botox and other cosmetic drugs, amassing a 9.7 stake in the company that was reportedly valued at more than $4 billion. In an unusual move, Ackman teamed up with Canadian-based health care company Valeant, which contributed $76 million to support Ackman’s acquisitions and agreed to pursue a joint bid for Allergan with Ackman’s assistance. If successful, the joint bid—which exemplifies Ackman’s penchant for bold activist tactics—could provide a new template for the structure of acquisitions. Critics have questioned the ethics of Ackman’s use of options to obtain $4 billion worth of Allergan stock to circumvent disclosure rules. The Allergan deal represents Ackman’s largest ever investment.

Ackman’s strategy was reportedly months in the making, beginning when Ackman hired his former Harvard classmate William F. Doyle, who was also friends with J. Michael Pearson, Valeant’s CEO. When Pearson and Ackman met to discuss potential partnerships, Pearson confided that he had sought to acquire Allergan for over a year. Ackman agreed to help make the acquisition a reality.

After Ackman acquired the position in Allergan with Valeant’s financial assistance, Valeant’s board met to settle on an exact offer price. A regulatory filing disclosed that Ackman planned to offer a cash component of $15 billion as part of the offer. If the deal succeeds, Ackman will retain a significant stake in the combined drug maker and would be contractually obligated to hold $1.5-billion of Valeant shares for one year following the merger. In the wake of the hostile bid, Allergan announced that it adopted a shareholder rights plan to allow its board more time to craft a response. The rights plan is designed to last one year, and it will become active if one or more shareholders acquire 10 percent or more of its shares.

Within days of the Ackman/Valeant move, in a bid to thwart Ackman’s hostile tactics, Allergan reportedly began preparing its own acquisition bid, targeting Shire PLC for a second time within a year. On May 13, a day after Allergan rejected its bid, Valeant said it would improve its unsolicited $47 billion takeover offer. Valeant is expected to unveil the improved offer at an open meeting to discuss the merger with shareholders of both companies scheduled for May 28.

Conclusion

By 2013, an estimated 100 hedge funds had adopted activist tactics as part of their investment strategies. To increase firm value, activist hedge fund managers often attempt to gain seats on boards, replace underperforming executives, seek alternative uses for the target company’s resources, and return cash to shareholders. Carl Icahn and Bill Ackman are two notable activist fund managers whose tactics put the spotlight on target company directors to respond quickly and capably to activist strategies. The case studies examined in this post are provided to contextualize the strategies activist fund managers employ and detail the tactics activists use to advance investor arguments for changes in target companies.

Print

Print