Mary Ann Cloyd is leader of the Center for Board Governance at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Catherine Bromilow and John Morrow; the complete publication, including interview insights, is available here.

Individual- and family-owned businesses are a vital part of our economy. If you or your family owns such a company you understand how important the company’s success is to your personal wealth and to future generations. If you’re a nonfamily executive at a family company, you also recognize that its profitability and resilience is vital to your job security and financial well-being.

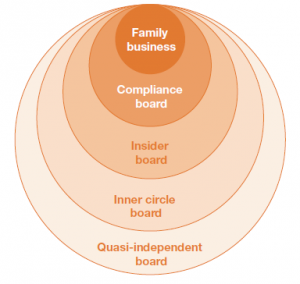

We see more family companies interested in corporate governance today than we did a decade ago, as shown in changes they’ve made to their boards. While some family companies have a board only to satisfy legal compliance requirements, more are moving toward the outer rings on the family business corporate governance model, below. Ultimately, owners will choose which level best suits the company’s needs and when changing circumstances mean the company’s governance should transition to another ring.

Family Business Corporate Governance Model*

* Some companies also have an Advisory Board to advise management (and directors). Advisory Board members don’t vote or have fiduciary responsibilities.

Compliance board. While most states require companies incorporated in the state to have a board, the requirement may be as simple as a board of at least one person that meets at least once per year. A company may have only the founder on its board. In the early stages of a founder-led company, this type of board may well be the best fit for the company, since the founder is usually more focused on building the business than on governance.

Insider board. Such a board often includes family members and members of senior management. This membership can better involve the family in the business, help with succession planning, and introduce additional perspectives to board discussions. The insider board may be created by the founder—who may no longer be the CEO—or by the next generation owner(s) of the company. That said, the founder/owner(s) retain decision-making authority.

Inner circle board. In this type of board the founder/owner adds directors he or she knows well. These may include an accountant, lawyer, or other business professional that guided or influenced the company, or the founder’s close friends. These directors may bring skills or experience to the board that are otherwise missing and may be in a position to challenge the founder/owner(s) in a positive way. Such boards might create an audit committee or other committees. That said, the founder/owner(s)—who may or may not be the CEO—retains decision-making authority.

Quasi-independent board. This level introduces outside/independent directors who have no employment or other tie to the company apart from their role as a director. (See the Family Business Corporate Governance Series module Building or renewing your board for a more complete discussion of independent/outside directors.) These directors introduce objectivity and accountability to the board and they expect their input to be respected. Board processes and policies will likely become more formalized with outside/independent directors on the board. The number of committees may increase. This outermost ring on the family business corporate governance model is most similar to governance at a public company.

We recognize that governance at any family company will be determined almost exclusively by what the founder (or family members who control the company) wants. You may have a compliance board or an inner circle board—and those may be entirely appropriate for where your company is at present. We’ve seen numerous family companies that benefited greatly from moving toward the outer rings in the governance model—especially when anticipating a generational transition.

In this post, we’ll help you understand how to build an effective board for your family company, and how boards can assist with some of the particularly challenging issues family companies face. This first module discusses why you might want to evolve or change your governance model and what you could expect from a board if you do so.

Each family company’s situation is unique and we can’t address every scenario. Our goal is to provide a framework of how corporate governance practices apply to family companies so you can decide what’s best for you.

Advantages of Evolving Your Governance Model

“Inner circle” or “quasi-independent” boards can add tremendous value to family businesses, including in the following areas:

Separating the company’s needs from the family’s needs

Especially in a company’s early years, founders and family members may view company assets as belonging to them. Removing assets—like significant amounts of cash—from a company can impact the company’s health, and even its viability. It can also have tax and regulatory consequences.

Directors can ask questions about how the company’s assets and profits are used. They can also help moderate discussions about the appropriate level of dividends for shareholders. This can help ensure the company retains sufficient funds so it can survive and grow.

Directors can leverage what they’ve seen elsewhere to help managers address challenges or perhaps avoid them in the first place. Some directors may also bring deep industry experience, which can be helpful when setting and implementing the company’s strategy.

Plus, directors often have extensive networks that can prove helpful to the company in other ways.

Help the CEO look beyond tactical issues

CEOs, especially in smaller family companies, often find themselves caught up in day-to-day operations with little time to think strategically about the business. Discussing strategy with a board can help the CEO focus on the big picture and spot trends, changes in the marketplace, and new opportunities.

Accountability

Periodic board meetings can help instill discipline in the executive team as managers will need to report on strategy, projects, financial results, and other matters.

Risk management

Directors can bring an outside perspective and discipline through overseeing risk management. They may bring different views on the importance of the risks that management has identified, and encourage executives to devote appropriate resources to addressing those risks.

Objectivity and independence

Often a company founder or CEO is the champion for certain projects and people. This can be great because it ensures a project will get needed resources and leadership attention. But sometimes it can be a problem if management doesn’t recognize when to pull the plug on something that’s just not working. Outside (i.e., nonfamily, nonmanagement) directors can bring objectivity that can help management make hard decisions when needed. And those directors may be in a better position to deliver sometimes difficult but necessary messages to the CEO.

Planning/advising on CEO succession

Because no CEO or founder lives forever, succession planning is critical. While a planned, orderly succession is ideal, a sudden illness or death could create a leadership vacuum. If the founder or CEO hasn’t considered succession, a board can encourage him or her to address it properly. Indeed, in an emergency an experienced director could even step in on a temporary basis until a permanent leader is found.

In the case of planned succession, the board can assist by encouraging the CEO to identify possible replacements and ensure internal candidates get the various operational roles to help prepare them for the possible chief executive role. (See the Succession planning module in this Series.)

Directors can also participate in coaching and mentoring family members who have joined the business and may aspire to run it one day. Given family dynamics, directors who are not related to the family may be able to identify—better than a parent or relative can—strengths and areas where a son or daughter (or niece or nephew) needs coaching. And those younger family members may be more receptive to receiving and acting on that advice from someone outside the family. By helping family members develop into effective business leaders, a board can improve the odds of a successful leadership transition within the family.

A safe harbor

If something goes wrong in a company—especially if it may involve a family member—employees or outsiders may find it easier to report concerns to directors who are not family members or part of the management team. The board can then decide whether to investigate further.

Smoothing ownership transition to the next generation

In our experience working with family companies, some falter when passing control of the company (which may be different from changing the CEO) from one generation to the next. An established board can provide continuity and guidance to a younger generation and help preserve the founder’s vision for the company. Effective directors build relationships with new family members who are added to the board.

Planning/advising on exit strategies

Sometimes passing the company down to the next generation isn’t the best move to maximize shareholder wealth or to ensure the company’s ongoing survival. A board can provide advice on whether the generation in control should:

- Sell the company

- Merge with another company

- Take the company public

- Wind the company down

Family companies also may have one or more outside investors, and these investors may have a time horizon for their exit from the business. A board can provide input on exiting with minimal disruption to the company.

Possible Concerns About Changing Your Governance Model

It’s all well and good to talk about the value a board can bring, but it’s not unusual for founders to have concerns about adding individuals to their board who aren’t either family members or close friends. Here are some of the common concerns and possible ways to address them.

I don’t want to give up control

If you’re the controlling shareholder you still get final say, regardless of what your board might suggest. You can also draft your delegation of authority policy to preserve the decisions you want to take.

I don’t want to share confidential information with outsiders

One way to avoid doing so is by having only insiders (family and management) on your board. If you choose to add other directors, you can remind them that they’re expected to maintain confidentiality about the company’s operations and results. You may consider reinforcing the expectation by having the directors periodically sign a nondisclosure agreement.

I have no time to go through the formalities of having a board

Having a board does require certain formalities—like preparing meeting agendas and materials, and recording minutes. And yes, these activities take time. Hopefully, your board is effective at bringing value so this time investment pays off.

In some situations these formalities can prove valuable. For example, if at a future point in time some family members allege that the company is not being run properly, having copies of meeting materials and minutes can help demonstrate that there was appropriate board oversight.

It’s expensive

Governance usually costs more as you formalize processes and add directors. If cash flow is a problem you could consider equity-like vehicles for director compensation. However you choose to compensate directors, you can assess whether they are bringing the value you need. If not, you can replace them.

Although it’s not a concern, per se, we also commonly hear from founders that they don’t need a board because they already know what’s right for their company. However, there could be a time when you’ll face a new situation where you are less certain about which direction to take. An established board that understands your business may help you respond to such challenges with sound advice and perspective.

What Can You Expect Your Board to Do?

Boards of private family companies have more flexibility in the roles they play than public company boards. Why? Because they’re not bound by the SEC and stock exchange listing rules that set responsibilities for public company boards and board committees. [1] Directors on private company boards do, however, have legal duties of care and loyalty (See the Building or renewing your board module in this Series for descriptions of these duties.)

There are certain standard responsibilities that boards typically have. Understanding what those are can help you better consider which responsibilities you want your board to take on. [2]

The owners of a family company may decide they don’t want the board involved in all these areas. For example the founder’s strategic vision may be so strong that he or she doesn’t want any input. That said, companies have failed when they missed the implications of a changing business or strategic environment, or were unsuccessful in their expansion efforts. And so we believe it’s worthwhile for whomever is running a family company to consider getting input in the areas described below before reaching major decisions.

Corporate strategy

Most executives agree that it’s management’s responsibility to develop the company strategy and then discuss it with the board. During this discussion, directors draw on their experience to challenge the plan and the appropriateness of the underlying assumptions. Often, the discussion will result in at least some changes to the strategy initially presented. Once management and the board agree on the strategy, the board will approve it and (in many cases) the budget needed to achieve it.

Company performance

How does the board know that management is executing the approved strategy effectively? By asking management to identify and set targets for key performance indicators that can be used to monitor progress. The board then monitors performance and discusses what remediation may be needed if performance is falling short.

CEO evaluation, compensation, and succession

No CEO knows everything—even if he or she founded or “grew up” in the company. For example, a founder who is a technology or service innovator may not fully understand the different financing options for growing the company to the next level. Or a CEO who has developed a concept largely alone may not understand how to build an effective team. An important role for private company directors can be to coach the CEO. That could include acting as a sounding board, helping the CEO manage through an issue, or having sometimes difficult conversations.

The reality is that founders or controlling shareholders who are CEOs usually determine their own compensation. But boards can be helpful in establishing performance targets and pay levels for CEOs who are other family members or professional managers. When a family member is the CEO, a good board can provide guidance and perspective about the appropriate level of compensation. And when the time comes to replace the CEO, whether planned or unplanned, the board will participate in hiring a new CEO. (See the Succession planning module in this Series.)

Risk management

A company might face risks as varied as new competitors, emerging regulations, unreliable IT systems, losing key people, or the impact of severe weather or other natural disasters on operations or the supply chain. Directors can provide feedback on whether they think managers are identifying the relevant risks and addressing those risks effectively.

It’s often difficult to determine how much risk a company should take. For example: Should it take on more debt to finance expansion into new countries or should it delay that expansion until it can self-finance? Should the company invest more into a product line that already accounts for a large part of its income or should it expand to other products to help spread its risk? There is no single correct answer to such questions, and directors can help executives determine the level of risk to take.

Significant investments and transformational transactions

Significant investments (say, purchasing a major product line, building a new plant, or establishing a strategic relationship) and transformational transactions (like mergers and acquisitions or divestitures) don’t always pay off as initially expected. Directors can ask questions to help ensure management focuses carefully on the expected costs and returns of a proposed transaction, and whether it fits with the company’s strategy.

Compliance with legal and ethical standards, the company’s “tone at the top,” and the company’s impact on its community

Most agree there is a clear linkage between long-term, sustainable performance and a company’s behavior as it relates to shareholders, customers, employees, and the communities in which it does business. That’s why many boards monitor the company’s moral compass. How? Partly by ensuring the CEO is setting the right tone at the top.

A board can also help ensure the continuity of the company’s culture through succeeding family generations and leadership changes.

External communications

The board can play an important role in ensuring that the information—whether favorable or unfavorable—the company communicates about its performance is reliable, relevant, and timely. And that includes overseeing the reliability of financial information that goes to the family, other shareholders and creditors, and any regulators or other authorities.

Board dynamics

Bringing the right people together is the first step to creating an effective board. What else is needed?

- An appropriate board structure, possibly including committees

- Enough meeting time to allow the board to carry out all of its responsibilities

- The right information to support board decision-making

- An environment that encourages candid discussions and healthy debate

One way some boards check on whether they are effective is to periodically assess their own performance.

Family company boards may face even more challenges than other companies in ensuring they have effective board dynamics. Why? Because sometimes family issues become intertwined with company issues. When the two overlap they can distract management and the board.

How many boards are involved in the responsibilities described above? A PwC 2013 survey asked CEOs and CFOs of 147 family-owned/owner-operated companies that question.

| What are the board’s main responsibilities? | |

| Monitor company performance | 85% |

| Set corporate strategy | 74 |

| Oversee/approve capital budget and key operating budgets | 62 |

| Set/approve compensation for top executives | 61 |

| Oversee risk management | 59 |

| Evaluate top executive performance | 56 |

| Succession planning | 56 |

These findings are similar to what the National Association of Corporate Directors found in its 2013-2014 Private Company Governance Survey.

| Which three governance issues are the highest priorities for your board in 2013? |

|

| Strategic planning and oversight | 57% |

| Corporate performance and valuation | 46 |

| Financial oversight/internal control | 27 |

| Risk oversight | 25 |

| Executive talent management and leadership development | 24 |

| CEO succession | 17 |

| Board effectiveness | 16 |

| Director recruitment and succession | 12 |

Questions to Consider

(1) Is our current approach to governance working for us right now? Do we expect it will be appropriate given anticipated changes to the company or the shareholder base in the near future?

(2) If we change our approach to governance, what should we do and how should we get there?

(3) What responsibilities should our board take on that it’s not currently doing?

Endnotes:

[1] See PwC’s publication Governance for Companies Going Public—What Works Best for a complete discussion of regulatory requirements. It’s available at www.pwc.com/us/en/corporate-governance/publications.jhtml.

(go back)

[2] See Board Effectiveness—What Works Best, 2nd edition, for a further discussion on board responsibilities. Information about this book is at www.pwc.com/us/centerforboardgovernance.

(go back)

Print

Print