The following post comes to us from Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP and is based on the executive summary of a Fasken Martineau study by Aaron J. Atkinson and Bradley A. Freelan, partners in the Mergers & Acquisitions practice at Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP. The complete publication is available here.

In Canada, there are numerous ways to acquire a public company; however, a take-over bid made directly to shareholders is the only means by which legal control can be acquired without the consent of the target board. Such an unsolicited (or “hostile”) bid is often used to bypass the board and present an offer directly to shareholders after discussions with the target board have failed, thereby putting the target company “in play”.

It is this unique characteristic of take-over bids that has generated such a spirited debate concerning the role of the target board and the appropriate scope of its powers in responding to a transaction that is, fundamentally, one between the bidder and the target shareholders. On the one hand, securities laws prescribe a principally advisory role, with the board being tasked with making a recommendation to shareholders. On the other, Canadian corporate law affords the board great latitude in managing the corporation’s affairs, theoretically allowing a board, within the confines of the business judgment rule, to “just say no” to stop a bid. That theory is not borne out in practice since the principal tool to forestall a bid, a shareholder rights plan (or “poison pill”), is inevitably temporal: when asked to do so, securities regulators have almost always rendered rights plans inoperable after a period of time, enabling the bidder to bypass the board and allowing shareholders to decide. This state of affairs has led some market participants to express the view that “the current Canadian approach generally favours bidders rather than targets and their shareholders, limits board and shareholder discretion and does not necessarily maximize value for shareholders”. [1]

In 2015, Canadian securities regulators will release a proposal to address these and other concerns by making significant changes to the Canadian take-over bid regime. Rather than imposing limits on the duration of rights plans or the actions of the target board, the proposed amendments will substantially increase the period during which a hostile bid must remain open, from 35 to 120 days, and mandate a minimum tender condition of a majority of the target’s shares. Shareholders, rather than the target board, will continue to be the final arbiters of any bid.

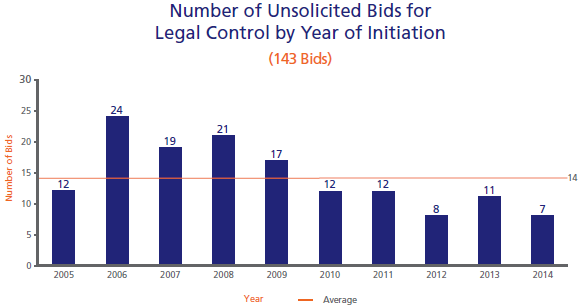

In an effort to contribute to the debate, we have conducted an empirical analysis of all 143 unsolicited take-over bids for legal control of Canadian-listed public companies during the ten-year period ended December 31, 2014. The parties making these bids were overwhelmingly “strategic” (90%) rather than “financial” (10%), confirming the prevailing view that financial buyers tend to shy away from the public pursuit of control in absence of the target board’s support. In addition, two-thirds of bidders were Canadian-based, with the balance comprised of US-based (22%) and foreign- based (11%) bidders.

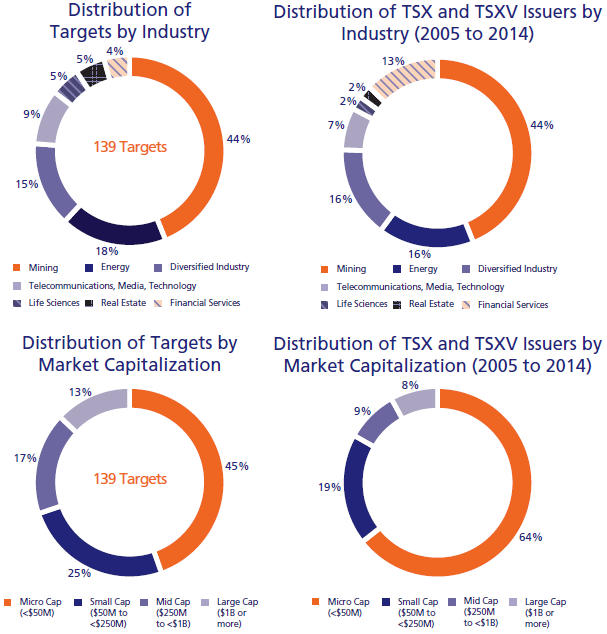

These 143 bids amounted to 139 contests for control, with concurrent bids for the same target arising on four occasions. The composition of issuers targeted roughly mirrored the composition of Canadian-listed issuers over the study period by industry sector (with financial services issuers significantly underrepresented, possibly due to the significant regulatory constraints on ownership of many such issuers) and market capitalization (with the exception of micro cap issuers who were significantly underrepresented, possibly due to the cost of conducting a formal take-over bid relative to the size of the issuer).

127 targets (91%) were the subject of a “first-mover” bid, meaning the bid was initiated in the absence of any other public acquisition proposal. To evaluate whether the Canadian take-over bid regime favours bidders, a logical starting point is to assess the outcomes in these contests as one might safely assume that, in most cases, the target board was not actively seeking a change of control when it was put “in play” by the bidder. While our study started there, it was not the end of our inquiry.

A small minority of targets (9%) were publicly proposing a change of control transaction when a hostile bid was announced, meaning the bidder willingly entered into a competitive auction. Competition also emerged to challenge many first-mover bids. We therefore separately assessed the impact, if any, of the auction dynamic on outcomes. Finally, while the outcome of any hostile bid is the product of numerous factors, we examined, to the extent practicable, the potential impact of certain key factors within the parties’ control, including the premium and form of consideration offered by the bidder, the target’s adoption of a rights plan and the target board’s recommendation.

Our analysis is offered in the hopes of advancing the current debate and is not intended to provide definitive answers. We trust that our study will be accepted in the spirit in which it is offered and, of course, we welcome your feedback.

Highlights

1. When initiating a public contest for control, a hostile bidder was successful more than half the time; however, the sale of the company was by no means inevitable.

A first-mover hostile bid succeeded almost 55% of the time. Coupled with those bids that were trumped by a successful white knight, more than 70% of Canadian-listed issuers were acquired once put “in play” by a hostile bid. At the same time, almost 30% of the targets of first-mover bids remained independent, so a sale of the company was by no means inevitable; however, the desirability of that outcome for shareholders might be questioned: on the first anniversary of the announcement of the bid, more than 60% of those targets traded at a discount to the final bid price.

2. Competitive scenarios occurred infrequently, but when they did, shareholders were the clear winners, while the hostile bidder was most often left empty-handed.

In a one-on-one battle with the target, a bidder won two-thirds of the time. When a bid faced competition, the target was acquired 86% of the time, but a bidder was successful in doing so only 33% of the time. Regardless of the victor, shareholders benefitted from competition since, in a competitive scenario, the final premium offered by bidders was, on average, 76% (an increase of 69% over the average final premium in the absence of competition). While bidders may rightly fear competition, it was not the norm, occurring only 37% of the time.

3. A hostile bidder’s odds improved when offering cash, and offering a healthy premium didn’t hurt either. But more than anything else, it paid to start from a position of strength.

More than three-quarters of all bids offered at least some cash, and for good reason: when facing no competition, a bid offering at least some cash won 72% of contests and, in a competitive scenario, an all-cash offer markedly improved a bidder’s odds of success (42% vs. 17%). While a higher initial premium did not deter competition, a premium of 30% or more carried the day almost 75% of the time in the absence of competition and, in a competitive scenario, a positive relative premium was more than three times as likely to result in success. But of all tactics a bidder may consider, accumulating a toe-hold position and locking up target shareholders proved to be a winning strategy, yielding an 87% success rate when a bidder’s starting position was 20% or more.

4. Shareholder rights plans proved their worth by buying time and driving competition.

Rights plans bought time for target boards by, on average, almost doubling the five week statutory minimum bid period before the bidder took up any shares. This additional time proved critical: where a first-mover bid faced competition, that competition emerged after the statutory minimum bid period almost two-thirds of the time. It should therefore come as no surprise that competition emerged to challenge a first-mover bid twice as often when a target had a rights plan.

5. The board’s support was a prized asset: hostile bidders had a near-perfect record when securing the board’s support and fared poorly without it, particularly where the board’s recommendation was more likely to influence the outcome.

Where a bidder ultimately won the support of the target board, the bid succeeded in all but one contest, or 98% of the time. In contrast, a hostile bid succeeded only 22% of the time in the absence of board support. Furthermore, a board’s decision not to support the bid aligned more frequently with the outcome in those cases where the board’s recommendation would be expected to have had greater influence: 80% alignment when no competition emerged and the target’s rights plan remained in force at the time of the board’s final recommendation;

83% alignment where the shareholder base was less concentrated among insiders such that the board was more likely to serve as both advisor and collective bargaining agent; and 95% alignment in the case of an all-share bid, which is more susceptible to the target board’s critique.

Looking Ahead

A hostile bid is a relatively infrequent event in Canada: of the roughly 3,700 publicly-listed companies in Canada, on average, only 14 were the target of a hostile bid in any given year over our ten-year study period. That isn’t to say that the threat of a hostile bid is an idle one—if a system truly favours one side in an adversarial setting, the behaviour (and bargaining power) of all parties will be informed by the greater likelihood that one outcome will prevail over others. Those concerned that the current system favours bidders over targets will no doubt take comfort from the fact that the new regime, if enacted as proposed, will strengthen the board’s hand, fundamentally altering the dynamics of future take-over negotiations, and may increase the odds of competition. Given the increased risks and potential costs to bidders in the new regime, we may well witness a decrease in the number of unsolicited bids, and perhaps of equal importance, a significant weakening of the very threat of a bid. To the extent that the reforms seek to enhance the auction dynamic with a view to increasing shareholder choice and maximizing shareholder value, that objective can only be achieved if bidders believe they have a reasonable prospect of success, justifying the risks inherent in launching a bid.

Endnotes:

[1] CSA Notice and Request for Comment: Proposed NI 62-105 Security Holder Rights Plans, Proposed Companion Policy 62-105CP, and Proposed Consequential Amendments (March 14, 2013).

(go back)

Print

Print