Emily Liner is a Policy Advisor at Third Way. This post is based on a Third Way publication. The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

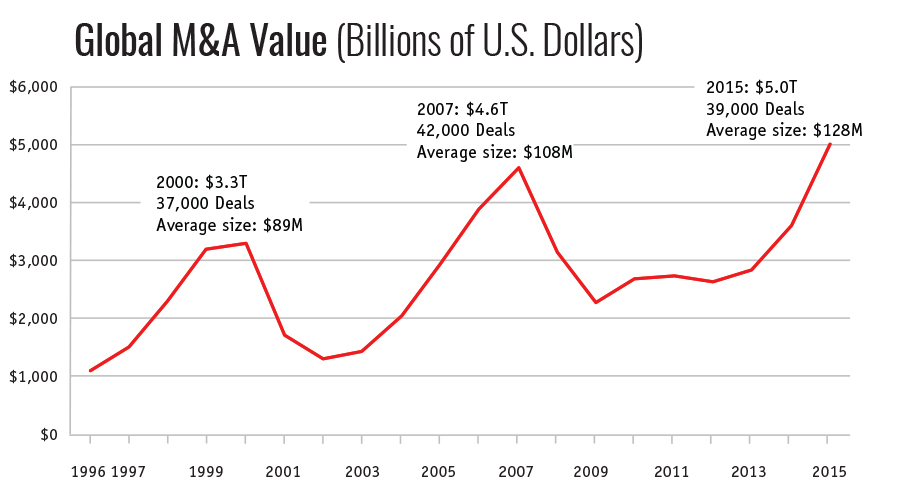

Headlines over the past year have been filled with news of mega-mergers. Big companies across numerous sectors and continents have been joining forces at record rates. Last year’s $5 trillion worth of deals worldwide was more than a one-third increase over 2014 and set a new high. Why the surge in M&A, and what does it mean for the broader economy?

What are mergers and acquisitions?

Mergers and acquisitions tend to be used interchangeably, but there’s a difference. In a merger, two companies agree to join together to form a new entity, whereas in an acquisition, one company subsumes the other. The opposite of an acquisition is a spin-off, which occurs when a company divests one of its internal businesses so that it can become a new, independent firm.

M&A deals generally come in two varieties: strategic and financial. When two companies strike a deal, it’s usually strategic in nature. They may be interested in gaining new sources of revenue through adding product lines, expanding into geographic markets, or acquiring new internal resources like intellectual property. Strategic deals allow firms to cut costs by combining processes, property, or personnel. One type of strategic, cross-border merger is called an inversion. This is when a U.S. company initiates a merger with a smaller foreign company; it is “inverting” by adopting the home—for tax purposes—of the smaller company.

Financial deals, on the other hand, are led by a group of investors, such as private equity (PE) firms. Unlike strategic buyers, who want to make acquisitions that complement their existing businesses, financial buyers are looking to invest in companies that they can enhance and sell at a higher price in the future. For the vast majority of start-ups, their journey ends with some sort of financial deal; 75% of start-ups accept an offer to be acquired, compared to just 11% that launch an initial public offering (IPO) and issue shares on the stock market. Through financial deals, PE firms help businesses access capital and talent that enable them to grow in scale. For these reasons, financial deals are generally a good thing for all involved, as well as for overall economic growth.

Another major difference to note between strategic and financial deals is that they generally have different types of funding. Relatively, strategic deals are more often paid for with cash or stock, while financial deals are more often backed by debt. Financial buyers may use a leveraged buyout (LBO) to fund an acquisition. In an LBO, a group of investors targets a firm to take over and, in the process, pledge the target’s assets as collateral to borrow the money they need to buy it. Although LBOs are a common structure for PE firms to build an investment portfolio, their use in bigger deals has been associated with hostile takeovers by activist investors who want to change a company’s management team.

Why are we talking about M&A?

1. The mega-merger explosion

Mega-mergers drove 2015 to the new record of $5 trillion, beating the previous high set in 2007. Strategic deals in particular have grown in size as larger and larger companies agree to merge or be acquired. There were 69 deals over $10 billion last year, beating the 2007 record of 43, and last year was the first time that 10 deals surpassed the $50 billion benchmark. We saw the biggest deals ever in health care, beverages, chemicals, tech, and food. And, for the first time, Asia outpaced Europe in total M&A.

Such large deals have many wondering how much longer the boom can last—and how painful it might be when it ends. One sign that a merger wave may be at its end is a pattern of falling stock prices for the companies involved in a deal on the day of its announcement. Research by economists Marina Martynova and Luc Renneboog notes that each previous wave of high M&A activity ended with a stock market crash. Many are wondering if that is in the cards in 2016 due to the exceptional volatility that has started the year.

What’s going on?

This chart shows three waves of global M&A activity over the past 20 years, with peaks in 2000, 2007, and 2015. In each peak year, the average size of M&A deals has grown. The total number of deals in 2015 went down, however, indicating that last year’s mega-mergers were an important factor behind the new M&A record.

2. Middle-market inertia

While M&A activity has exploded for companies valued over $1 billion, it has never quite regained its pre-recession momentum in the $10 million to $1 billion category known as the middle market. This is the segment that many start-ups, family businesses, and successful private firms inhabit, and it’s where financial buyers like PE firms tend to play. In the middle market last year, there were 2,220 deals for a volume of $297 billion, slightly down from 2014. Although these figures are well below the 2007 high of 3,567 deals for $423 billion, they are still in line with middle-market deal making over the past five years. Some surmise that this overall decline may be a function of new rules, set in the aftermath of the crisis, that are intended to limit riskier forms of bank lending.

Others say that this dichotomy between mega-mergers and the middle market is simply a consequence of market conditions. Lately, financial buyers have been on the sidelines because valuations—the asking prices—of companies for sale are on the rise. The back-of-the-envelope way to measure this is to divide the valuation of the company by its annual earnings. The result is the multiple. Last year, acquirers paid a 10.3 average multiple on middle-market targets. That tops the 9.7 average multiple in 2007, even though the economy was seemingly much better then (before markets caught onto the financial crisis). Multiples and valuations matter to financial buyers like PE firms because their value proposition is to create higher returns than investors could achieve otherwise. And those investors aren’t just wealthy individuals; they’re also groups that support working Americans like pension funds. So financial buyers will hold back if they can’t negotiate for a price that meets their required internal rate of return on investment.

Why so much M&A?

There are five major factors leading to the explosion of M&A among large firms: slow economic growth, weak consumer demand, cheap money, tax arbitrage, and China.

1. Slow economic growth

Between 1950 and 2000, growth averaged 3.7%. Since 2000, however, growth has averaged only 1.9%, and the last time growth exceeded 3% was 2005. Many economists have described the slowdown in output, productivity, and population growth as the “new normal.”

Worldwide, growth has also been lackluster. Advanced economies have been essentially treading water for the past five years. The Eurozone, for example, grew just 1.5% in 2015 and is expected to hover around 1.7% for the near future.

Public companies are compelled to figure out how to generate higher profits and satisfy impatient investors in a low-growth economic environment. One answer is through a merger or acquisition which can lower costs and increase market share.

2. Weak demand

In his 2013 book, investment banker and author Daniel Alpert writes of the problems economies face in “an age of oversupply.” In short, he argues that there are not enough middle-class consumers worldwide to purchase new products. Firms fear that if they produce more goods there won’t be enough buyers. This has led companies to hoard cash, conduct stock buybacks, and acquire companies as a way to juice returns. This helps explain why nonfinancial firms in the S&P 500 reported over $2 trillion in cash on hand in October 2015, an increase of 8% over 2014.

On the consumer side, relatively flat wages in the U.S. have been coupled with higher savings rates and decreased consumer demand. More earnings are being tucked away into savings rather than spent.

When consumers scale back, that limits companies’ ability to grow through sales, or what the business world calls organic growth. Regardless of these headwinds, CEOs are still expected to deliver profits to their shareholders and show a record of improvement. So how else can companies grow? For these mature firms, the easiest way to get back on the path to growth is to acquire one of these startups or to merge with a competitor. The same forces propelling the new firms forward also push older firms to consolidate.

3. Cheap money

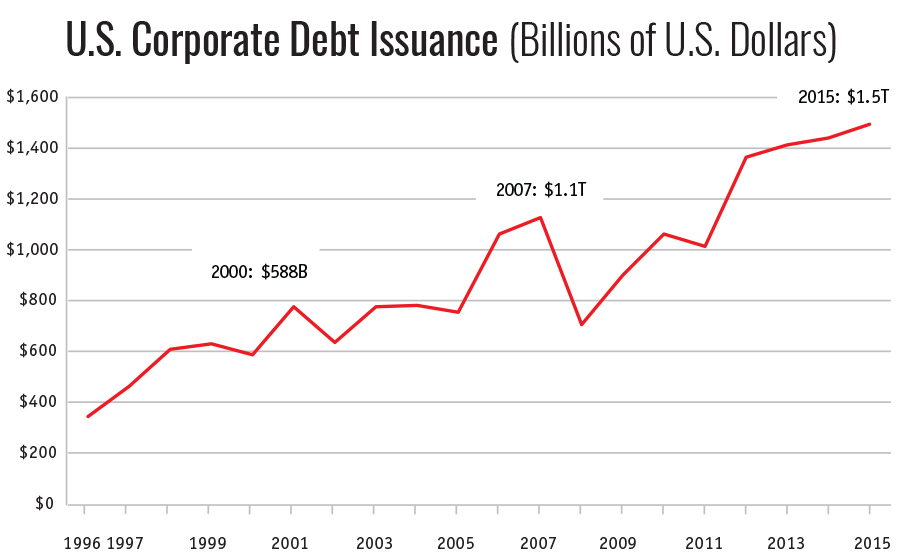

By using debt or equity, companies can hang onto their cash to invest it in R&D, raise wages, pay dividends, or save for the next rainy day. The ability to borrow at historically low interest rates makes debt financing of deals very attractive right now. In addition, because interest payments are tax-deductible, a debt-financed deal can be less expensive than a deal financed by equity or even sometimes cash.

Now that the Fed has started to gradually raise rates, cheap debt may not be around forever. That means that companies are incentivized to act now, before rates go up further. Indeed, corporate bond issuance is at a new peak, topping $1 trillion through the first three quarters of 2015, to help pay for all of this M&A.

For mergers of equals, companies often choose to finance deals with equity. In deals like these, the shares of the two companies go into a common pot and shareholders receive an allotment of shares from the new combined company based on an assigned conversion rate. The percentage of deals involving stock increased to 33% in 2014 from 19% in 2013. With low interest rates, lots of cash on hand, and relatively high stock prices, there are many opportunities for M&A.

What’s going on?

Corporate debt issuance typically increases through the peak of a merger wave. Since the depths of the 2008 financial crisis, new corporate debt issuance has doubled, due in no small part to the extremely low interest rates of recent years. Corporate debt issuance is not inherently problematic and is a common form of funding for large acquisitions.

4. Tax arbitrage

While inversion deals make up a large share of headlines, they are actually a relatively small portion of global M&A. According to Bloomberg, there were nine inversion deals last year. The total value of these inversions was $236 billion, which is a fraction of the $2.5 trillion of M&A involving U.S. companies.

Still, inversions are on the rise and have garnered attention accordingly. They are happening because American companies face a growing tax incentive to incorporate abroad. Over the last two decades, many developed countries have reformed their tax codes to be more competitive and suitable to the modern economy. The United States has not. That has left a growing disparity between the U.S. system and those of European countries in particular. The U.S. has the highest statutory rate in the world, at 35%; its code is cluttered with an abnormally large number of rules and special preferences; and our international tax laws put U.S.-based corporations at a disadvantage when competing abroad.

As the competitiveness gap between the U.S. and Europe has grown, so has the incentive for U.S. companies to move their headquarters to tax-friendly nations like Ireland. But a U.S. company cannot just get up and go—there are tax penalties for that. The tax code does allow, however, for a U.S. corporation to relocate abroad if it combines with a foreign company at least one-fourth its size. To improve their competitiveness internationally, this is exactly what some U.S. companies have done.

It should be noted that inversions don’t necessarily lead to direct job losses—often physical facilities remain in the U.S.—but they do result in the narrowing of the U.S. tax base. Until the U.S. adopts a more competitive corporate tax code, there will remain an incentive for U.S. companies to merge with foreign counterparts. And there will remain an incentive for more conventional, cross border non-inversion acquisitions. Some U.S. firms—particularly those with large portions of their profits overseas have become acquisition targets of larger overseas companies living under more favorable tax rules.

5. New actors

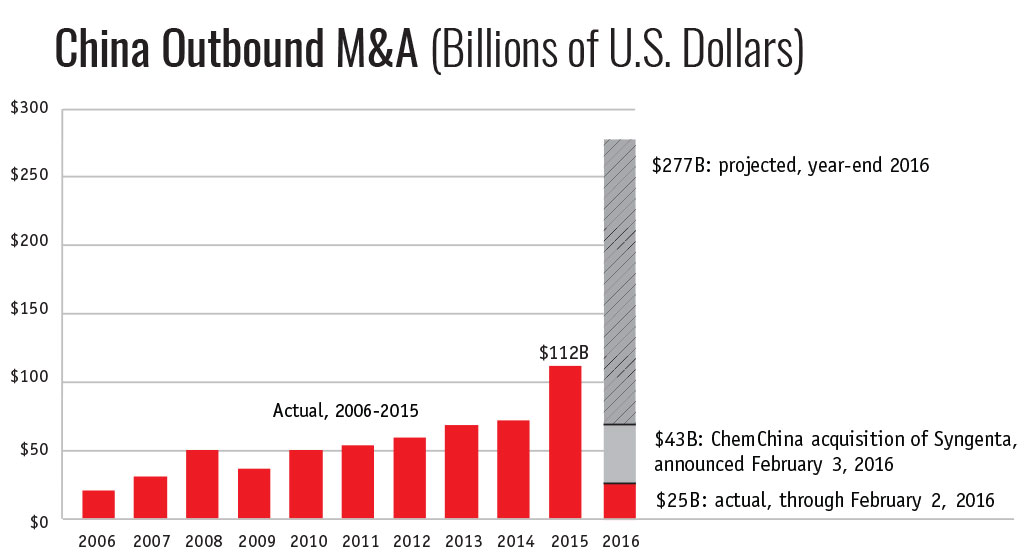

Emerging markets usually fuel overall global growth, but even these dynamos are beginning to slow down. According to the IMF, growth in emerging markets and developing economies has fallen for five years in a row. Nowhere is this embodied more than in China. China’s GDP growth last year was the slowest reported since 1990. Meanwhile, heightened capital controls have driven Chinese firms to search for any way possible to invest money abroad.

One solution: Acquire foreign companies. In fact, outbound M&A from China surpassed $100 billion for the first time last year. And in just the first five weeks of 2016, China has already matched its 2013 level of outbound M&A, thanks to ChemChina’s $43 billion offer for the Swiss agricultural chemical manufacturer Syngenta—the biggest-ever foreign acquisition by a Chinese firm.

China’s appetite for U.S. targets has also gotten stronger. Until recently, the biggest Chinese acquisition in the U.S. was Shuanghui International Holdings’ $7.1 billion buyout of Smithfield Foods in 2013. Compare that to last year, when state-owned enterprise Tsinghua Unigroup made a $23 billion bid for Micron Technology. It would have been over three times bigger than the Smithfield deal, if Micron had accepted it. But China is still pushing forward; as of February 2, 2016, Chinese outbound M&A activity into the U.S. already exceeded the $20.6 billion total from all of 2015. Even small Chinese bids are facing scrutiny, like the $100 million offer for the Chicago Stock Exchange from Chongqing Casin Enterprise Group.

What’s going on?

This chart shows how much M&A activity from China to foreign targets has increased over the last decade. Last year’s outbound M&A activity of $112 billion was 57% bigger than in 2014, and more than double 2011. At 2016’s rate thus far, excluding the record-setting ChemChina-Syngenta deal, China could end the year with as much as $277 billion in outbound M&A.

Conclusion

Even if the pace of M&A slows down from its recent high, it will continue to be part of the economic landscape. In a healthy, dynamic economy, companies morph to stay competitive. Some companies may be better off merging or closing, while others are born through spin-offs and entrepreneurship. All of these possibilities keep our economy moving forward. And for promising new businesses—those known to be most responsible for job creation—mergers can provide access to human talent and capital that enable them to grow.

Yet M&A can also come with downsides for some involved, which is why we have a system of formal and informal checks and balances:

- Mergers can lead to job losses for the firms involved, as managers carry out plans to consolidate the companies’ workforces. When that is the case, unions and the court of public opinion can elevate the voices of workers.

- Reduced competition can result in limited consumer choice and higher prices. That’s why the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division can overrule mergers that threaten to hurt consumers.

- Sometimes, the expected benefits of a deal fail to materialize, putting the new firm in jeopardy. But shareholders can push back against bids that don’t add up—and often they do.

- Finally, national security can enter the picture. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) reviews M&A bids from foreign firms and blocks those that threat national security or critical infrastructure.

Ultimately, mergers are an essential element of a growing economy, and they will continue to ebb and flow with economic conditions.

Print

Print