Andrew J. Patton is the Zelter Professor of Economics and Professor of Finance at Duke University, and an Associate Member of the Oxford-Man Institute of Quantitative Finance. This post is based on a forthcoming article by Professor Patton; Tarun Ramadorai, Professor of Financial Economics at Imperial College London; and Michael Streatfield, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford.

What do we know about hedge funds?

Despite the miles of column inches devoted to the hedge fund industry in the financial and popular press, relatively little is known about their trading strategies, risk profiles, liquidity needs, or potential for impact on systemic risk. In the wake of the recent financial crisis, the Securities and Exchange Commission proposed a rule requiring U.S.-based hedge funds to provide regular reports on their performance, trading positions, and counterparties to a new financial stability panel established under the Dodd-Frank Act. A modified version of this proposal was implemented in 2012, and requires detailed quarterly reports for 200 or so large hedge funds (those managing over $US 1.5 billion) and less detailed, annual, reports for smaller hedge funds. The proposal makes clear that these reports are only available to the regulator, with no provisions in the proposal regarding reporting to funds’ investors or to the public more generally.

One significant disclosure that hedge funds offer to a wider audience is reports of their monthly investment performance. This self-reported information is provided by thousands of individual hedge funds to one or more publicly available databases, which are widely used by researchers, current and prospective investors, and the media. Performance disclosures (as well as disclosures on fund size and a few other fund characteristics) are considered to be one of the important ways that hedge funds market themselves to potential new investors (see Jorion and Schwarz, 2014, for example) given investors’ reliance on this information to distinguish between funds. The importance of these disclosures was even greater prior to 2014, during which period advertising by hedge funds was precluded by the SEC and CFTC.

Hedge Fund Data Revisions

In our 2015 Journal of Finance article, we closely examine hedge fund disclosures to these publicly available databases, and contribute to the debate on hedge fund disclosure regulation. Specifically, we ask whether these voluntary disclosures by hedge funds are reliable guides to their past performance, and attempt to answer this question by tracking changes to statements of performance in “vintages” of these databases recorded at different points in time between 2007 and 2011. In each such “vintage,” hedge funds provide information on their performance from the time they began reporting to the database until the most recent period.

We find that in successive vintages of these databases, older performance records (pertaining to periods as far back as fifteen years) of hedge funds are routinely revised. This behavior is widespread: close to 45% of the 12,128 hedge funds in our sample have revised their previous returns by at least 0.01% at least once, and over 20% of funds have revised a previous monthly return by at least 1% (see Table 1 below). These are very substantial changes, given the average monthly return in our sample period of 0.62%.

Table 1: Size of Revisions

| Fund Count | at least 0.01% | at least 0.1% | at least 0.5% | at least 1% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funds | 12,128 | 5,446 | 4,718 | 3,363 | 2,581 |

| % of Total Funds | 100.0% | 44.9% | 38.9% | 27.7% | 21.3% |

We are careful to check whether these revisions are potentially attributable to corrections of data entry errors (such as sign errors or digit transpositions). However, we find that such potential corrections account for less than 2% of all revisions, meaning that over 98% of the revisions are attributable to something other than innocuous errors.

We also study the “age” of the return that was revised. If the return initially reported by a hedge fund manager was an estimate, perhaps based on an estimated valuation for an illiquid investment, then it might be reasonable to expect subsequent revisions of the initially reported return. To evaluate this explanation, we report the age of the revised return, and find that around a quarter of the revisions that we identify relate to returns that are less than 3 months old (see Table 2 below). However, we also find that almost one half of all revisions relate to returns that are more than 12 months old.

Table 2: Age of Revised Returns

| at least 1 month | more than 3 months | more than 6 months |

more than 12 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revisions | 87,461 | 63,791 | 51,426 | 43,192 | |

| % of Total Revisions | 100.0% | 72.9% | 58.8% | 49.4% | |

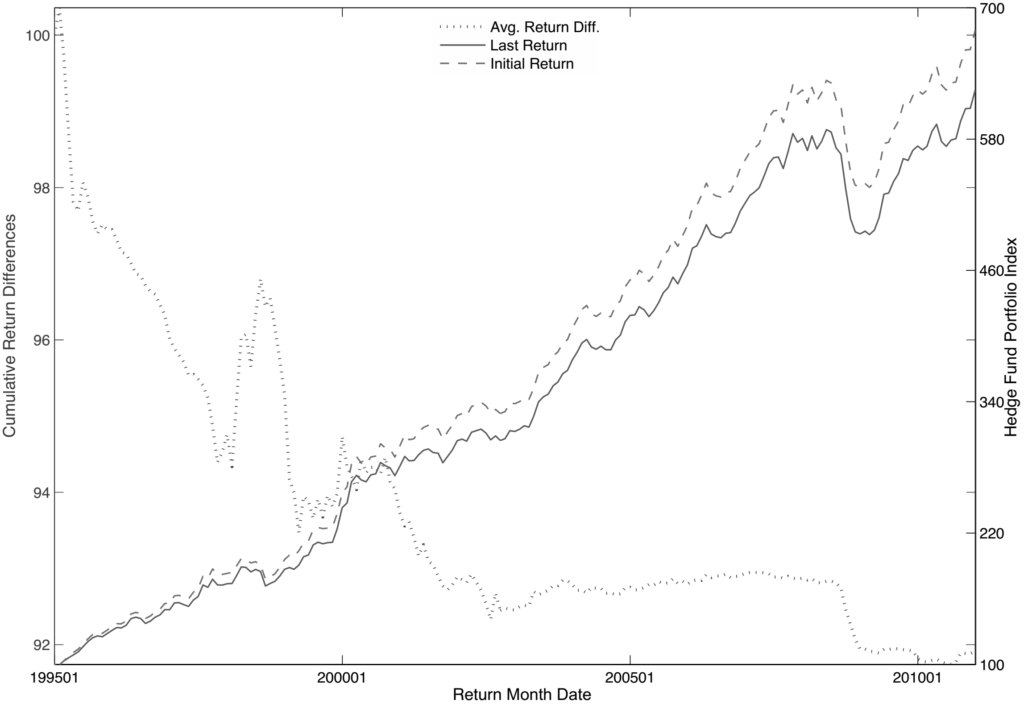

Investigating the pattern of revisions more thoroughly, we find both positive and negative revisions in our sample. However, negative revisions are more common and larger when they occur, i.e., on average, initially provided returns present a rosier picture of hedge fund performance than finally revised performance (see Figure 1 below). This suggests the danger of prospective investors being wooed into making decisions based on initially reported histories which are then subsequently revised.

Figure 1: Cumulative Differences between Last and Initial Returns

Finally, to understand whether there is any predictive content to knowing that a fund has revised its history of returns, we analyze the out-of-sample performance of revising and non-revising funds. At each vintage of data, we categorize hedge funds into those that have revised their return histories at least once (revisers) and the remainder (non-revisers). Following the performance of these funds in the future, we find that non-revising funds significantly outperform revising funds. The magnitude of the average out-performance (measured by “alpha”) is around 30 basis points a month, or 3.6% annually, and is not explained by differences in exposures to various factors that previous researchers have used to explain hedge fund returns (see Table 3 below, which includes the alpha when no factors are used, a standard market factor is used, or the Fung-Hsieh (2001) seven-factor model for hedge fund returns). This finding suggests that while there may be several innocuous reasons for revising past returns, it nevertheless constitutes a negative signal about the future performance of the fund.

Table 3: Monthly Return Differences between Non-Revisers and Revisers

| Model: | None | Market | Fung-Hsieh |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Alpha |

0.309* | 0.309* | 0.278* |

| (t-statistic) | (3.805) | (5.133) | (3.053) |

Looking forward

Recent policy debates on the pros and cons of imposing stricter reporting requirements on hedge funds have raised various arguments. The benefits of disclosures include market regulators having a better view on systemic risks in financial markets, and investors and regulators being able to better determine the true, risk-adjusted performance of funds. Costs include the administrative burden of preparing such reports, and the risk of leakage of valuable proprietary information on trading strategies that may be backed out from portfolio holdings. Our analysis suggests that mandatory, audited disclosures by hedge funds, such as those implemented in 2012, would be beneficial to regulators. Our analysis additionally suggests that it would be worth considering whether these reporting guidelines, which currently only apply to funds’ disclosures to regulators, could also apply to disclosures to prospective and current investors. Our analysis suggests that such information would help hedge fund investors make more informed investment decisions.

The complete article is available here.

References

Fung, William, and David A. Hsieh, 2001, The risk in hedge fund strategies: Theory and evidence from trend followers, Review of Financial Studies 14, 313-341.

Jorion, Philippe, and Christopher Schwarz, 2014, The Strategic Listing Decisions of Hedge Funds, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 49(3), 773-796.

Patton, Andrew J., Tarun Ramadorai, and Michael Streatfield, 2015, Change You Can Believe In? Hedge Fund Data Revisions, Journal of Finance, 2015, 70(3), 963-999.

Print

Print