Emiliano M. Catan is Assistant Professor of Law at New York University School of Law. This post is based on his recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Toward a Constitutional Review of the Poison Pill by Lucian Bebchuk and Robert J. Jackson, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Does the presence of a poison pill really matter for firm value? There are good reasons to believe that when it comes to pills, what really matters is their availability, and not whether they have been adopted. After all, even a firm that has not adopted a poison pill can quickly adopt one if a hostile bid arises. (Coates, 2000). However, empirical studies over the past few years (Bebchuk et al., 2009; Cremers & Ferrell, 2014; Cremers et al., 2016) have documented that the actual presence of pills is negatively associated with firm value (Tobin’s Q).

Although those studies suggest that the association may reflect a causal effect of the presence of pills, their methodologies are not airtight: They are still incapable of ruling out stories whereby firms adopt (or drop) pills in response to changing conditions correlated with firm value.

In my paper The Insignificance of Clear-Day Poison Pills, I follow over 2100 publicly traded firms from 1996 to 2014 to revisit the relationship between firm value and clear-day poison pills—i.e., pills that are adopted in a purely preemptive way, and not in response to bids, stock accumulations, etc. Using my data, I show that the reason why pills are negatively associated with firm value is not that the pill’s adoption leads to a drop in firm value, but the other way around: Firms tend to adopt pills following a substantial drop in their value.

My paper improves upon the methodologies used in earlier analyses by taking increasingly closer looks at the seeming negative association between pills and firm value. I break up the within-firm association into its two components: the association that is driven by pill adoptions and the one that is driven by the dropping of pills. I then document that pill adoptions—and not the dropping of pills—are the exclusive drivers of the within-firm negative association between pills and firm value. As I argue in the paper, the dropping of pills was less likely to be driven by value-related considerations than the adoption of pills. Consequently, the fact that all the within-firm results are driven by adoptions heightens the concerns that those results may be tainted by selection bias.

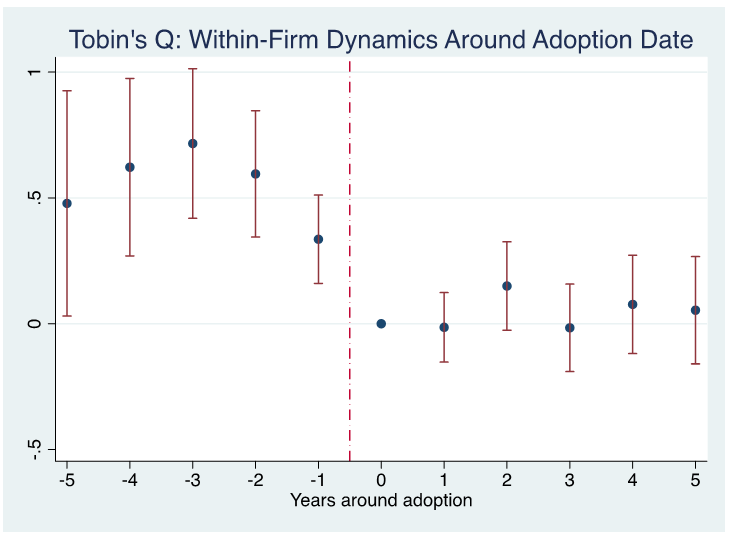

I also take advantage of the richness of my hand-collected data to study the dynamic evolution of firm value in the 10-year window around the adoption of a pill. Focusing on annual data, I document that, although firm value seems to drop significantly during the year of adoption of the pill, firms that adopt pills only do so after having experienced a very substantial relative drop in value over multiple years (see Figure 1). This stylized fact suggests that the “parallel trends” assumption that is necessary for difference-in-difference analyses to be identified is not satisfied. In plain English, if the value of eventual pill-adopters dropped in the years leading to the adoption of the pill, one cannot infer that the drop in value experienced in the year in which they adopt the pill can be ascribed to the adoption of the pill.

Figure 1

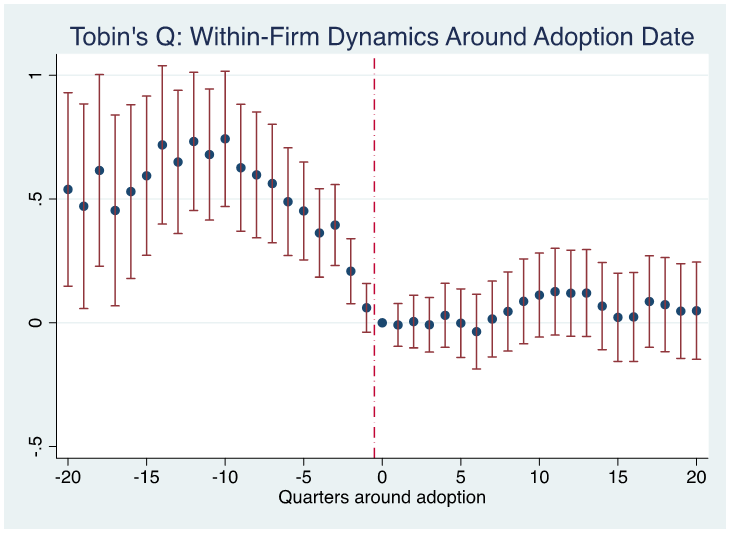

Using quarterly data, I document that (a) the drop in value experienced during the year in which firms adopt the pill is driven by a sharp drop in value in the third and second quarters before the adoption of the pill, (b) that firm value does not drop significantly in the quarter during which the pill is adopted, and (c) that it remains stable thereafter (see Figure 2). The data also reveals that firms adopt pills in the wake of sharp—and to a large extent temporary—drops in their operating performance, and that following the adoption of the pill firms significantly cut back their investments in R&D.

Figure 2

These results indicate that—at least during the past two decades—the ostensive negative effect of pills on firm value is due to reverse causality and that prior analyses were incorrect in concluding that pills are harmful and using pills as indicators of “bad governance” (as, for example, reflected by widely used academic and commercial corporate governance indexes). Additionally, the results call into question the usefulness of the dramatic drop in the incidence of clear-day pills that took place during the last decade due to the pressure of ISS and institutional investors.

The full paper is available for download here.

Print

Print