Mark B. Nadler is Principal and co-founder of Nadler Advisory Services. This post is based on a Nadler publication.

These can be difficult days for anyone in management who frequently deals with the company’s board of directors. That once-comfortable relationship between management and the board, particularly in public companies, is being strained by unprecedented change. It often plays out in ways that can feel intrusive and irritating—requests for more data, reports, presentations and meetings—all requiring more time, effort and attention. That can feel awfully frustrating when the new demands appear in a vacuum, without explanation.

So, for those leaders other than the CEO (and possibly the CFO and Corporate Secretary), who generally see only isolated slices of the unfolding relationship with the board, here is a look at the broader, game-changing context in which these changes are happening.

The headline: Without question, most boards are demanding more of management, but not because directors have capriciously decided to grab more power. To the contrary, boards are responding—often, with great unease—to escalating demands from all sides to exercise unprecedented oversight in ways that sometimes blur the traditional distinctions between boards and management. Here are six trends that help to explain what’s changing, why, and the implications for top managers.

Trend #1—The Mega-Trend: The Balance of Corporate Power is Shifting from the CEO to the Board

The long, often cozy relationship between CEOs and boards was irreversibly upended by the ugly corporate scandals of the early 2000s. Reacting to horrendous management decisions driven by unrestrained greed, shareholders, politicians and the press all pinned ultimate responsibility on weak and inattentive boards; directors were accused of being “asleep at the switch.” The immediate response was a slew of tough new governance requirements imposed by the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation and listing requirements for companies traded on public markets. (It’s worth noting that many private companies have voluntarily adopted many of the same requirements and, as a result, experienced some version of the trends discussed here.)

Just a few years later, reckless corporate behavior helped fuel the 2008 financial crisis. The result was even more aggressive government regulation (the controversial Dodd-Frank rules), greater influence by proxy advisory services that monitor governance practices and, most importantly, heightened attention from the large institutional shareholders that now control about 70% of publicly traded stock in the U.S. Those forces have hastened the gradual disappearance of the “Imperial CEO” and shifted the balance of power from the C-suite to the board room.

Until fairly recently, most U.S. boards tended to be handpicked by the CEO. These days, it’s becoming harder—though by no means impossible—to find boards consisting largely of the CEO’s submissive, hand-picked friends and business associates. It wasn’t that long ago that one of the best-known of the imperial CEOs—Disney’s Michael Eisner—could have his personal lawyer, his architect, and the principal of his kids’ school sitting on the company’s board of directors. Without question, there are still far too many boards—Yahoo’s is a recent example—where some directors have strong, long-term relationships that undermine true independence from management. Nevertheless, the CEO’s boardroom influence has decreased quite swiftly:

- Through the mid-1990s, the titles of CEO and Chairman of the Board were jointly held by the same person at more than 80 percent of U.S. public companies; today, that number is down to 43 percent.

- Today, fully 85 percent of public company directors qualify as “independent”—they are neither employed by, nor do business with, the company or the CEO;

- On the great majority of public company boards, the CEO is the only non-independent director, and powerful committees can only be chaired by independent directors.

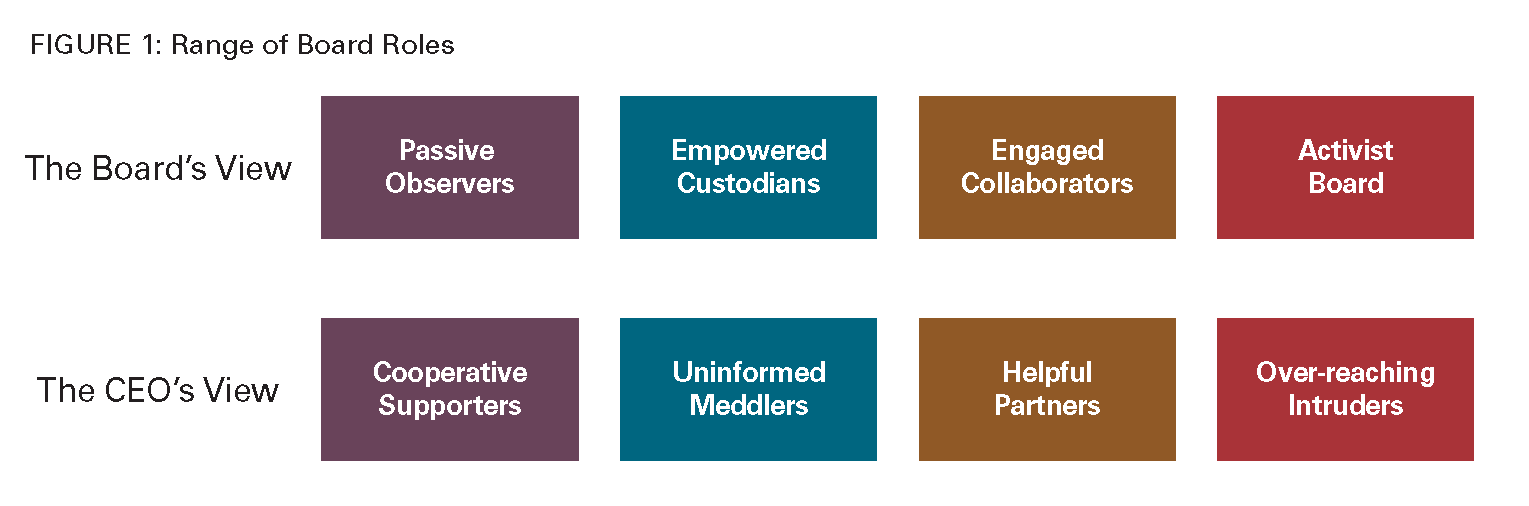

Those changes, and others, have strengthened the board’s role as ultimate guardian of the shareholders’ interests. But the tone and substance of those changes—as well as management’s reaction—differs at each company. What looks to some directors like long overdue reform can strike some CEOs and senior executives as dangerous infringements on essential management prerogatives.

Make no mistake: More and more CEOs understand the board’s potential as a valuable resource rather than a necessary evil. Effective boards help the CEO to avoid bad decisions and make better ones. Good boards bring a wealth of experience, knowledge and insight to the table—and confident CEOs welcome that. But reaching that point of mutual respect isn’t always easy. A major shift in the relative balance of power within any relationship provokes a range of emotional responses, and the relationship between the CEO and the board is no different.

Trend #2: The Board’s New Role Requires a New Level of Performance

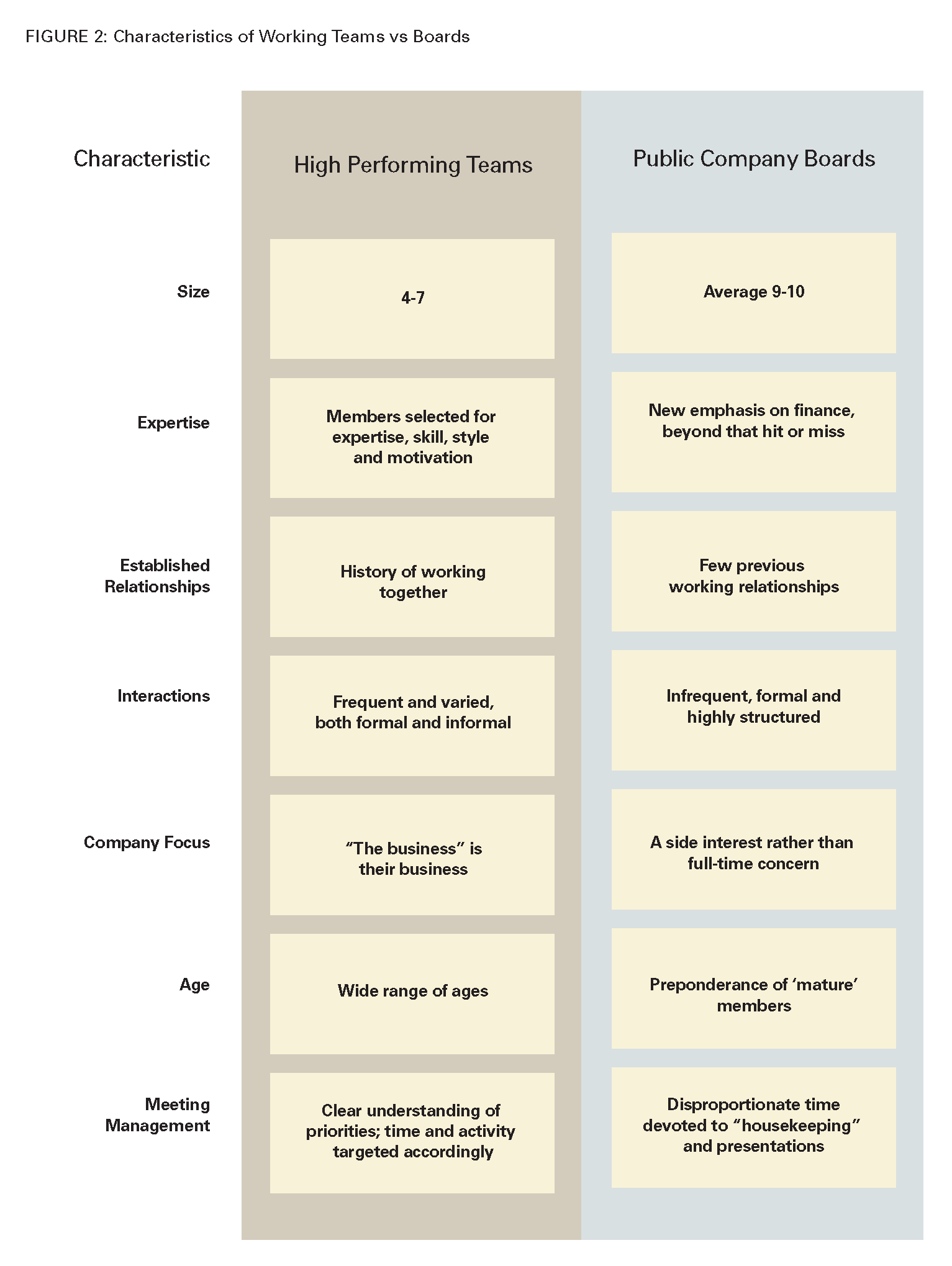

To meet the new demands, directors need to roll up their sleeves and dig into real work. At a great many boards, that requires a fundamental transformation from a ceremonial gathering to a high-performing team. Therein lies the problem: Public company boards were never intended or designed to do real work, and as result, share almost none of the characteristics common to high performing teams.

The best boards are tackling these inherent deficiencies. Boards and their committees are meeting more frequently, both in person and electronically. The average time committed by each director to a public company board has expanded from 90 hours a year at the beginning of the century to 250 hours today, the equivalent of a full month’s work. Boards are reexamining their committee structure, work processes, information flow, meeting schedules, agendas. In the best cases, boards are reassessing their own leadership, culture and social dynamics as they strive to improve their performance.

Though these are positive changes, they are not without cost. The increased workload by the board inevitably spills over onto those in management who support both the information flow and logistics for the board. If you haven’t yet experienced that burden, it’s only a matter of time.

Trend #3: The Board Wants Deeper Involvement in Strategy and Talent

For some time now, directors have identified strategy as the topic on which they’d most like to be more involved. Yet, despite that interest, the quality of engagement has been disappointing. A recent McKinsey study found that:

- Only 34% of directors believe their board fully understands their company strategy

- Just 22% think their board understands how the company creates value

- A mere 16% say their boards understand the dynamics of their company’s industry. Similarly, PwC’s Annual Corporate Directors Survey found last summer that over the previous year:

- 24% of boards had failed to examine major global trends affecting their business;

- 43% had not looked at potentially disruptive initiatives by competitors

- 50% failed to consider any alternatives to management’s strategic options.

My experience supports those dismal numbers. I once worked with the board of a Fortune 500 manufacturing firm whose long-time CEO wanted to crown his tenure with the construction of a new $800 million processing plant, even though the industry was plagued by global overcapacity. When I asked board members if they had any reservations, they invariably responded, “Oh, the CEO knows way more about strategy than we do—we leave that to him.” When I asked the CEO if I might see the corporate strategy statement, he smiled, tapped his forehead and said, “It’s all up here.”

Major shareholders are losing patience with situations like that. Early this year, in his annual letter to 500 CEOs, Larry Fink—the CEO of BlackRock, the $5 trillion investment firm—demanded that each company BlackRock invests in must demonstrate that there has been a strategic review, “a rigorous process that provides the board with the necessary context and allows for a robust debate. Boards have an obligation to review, understand, discuss and challenge a company’s strategy.”

Similarly, shareholders are turning up the heat on some boards’ inattention to executive talent. A 2014 study by the Conference Board and Stanford University found that only 55 percent of directors were confident that they really understood the strengths and weaknesses of their senior executives. PwC’s annual board report found that only 34 percent of directors think their board does a great job of overseeing talent management and succession planning, and only a third said management included an analysis of talent-related risks with each strategic initiative. Our own research, published last year in both HR and board professional publications, produced an even more troubling result: only 12 percent of the directors we surveyed said their head of HR contributed major value to their consideration of risk management, which raises frightening questions about boards factor talent and culture into the risk equation.

The pressure on boards to get up to speed on both strategy and talent is intense, and the implications are clear. Expect more meetings, presentations and information requests as the board becomes an integral part of the annual strategy process. Look for boards to seek more opportunities to meet with the top team, as well as more junior executives, in venues outside the board room. Many directors are realizing that their primary interactions with managers occur in one of the most unnatural settings you can imagine: formal board room presentations, which reveal almost nothing about a manager other than their ability to deliver formal board room presentations.

Trend #4: The Board is Getting More Serious about the Quality of its Own Composition

Far too many U.S. boards still fit the traditional mold of “pale, male and stale.” (I recall an unusually frank discussion of diversity in one board room, where an exasperated director exclaimed, “Look around this table! This looks like a Ku Klux Klan meeting, not a Fortune 500 board!”) Today, both the average age—63—and the average tenure—8.5 years—for public company directors is actually increasing. The percentage of women—22 percent—and minorities—9 percent—rose gradually in recent years, but has now leveled off.

Apart from specific numbers, an absence of demographic diversity can also be a warning signal that the board suffers from limited perspectives and a shared mindset. Even beyond demographics, the greatest gaps in board composition involve relevant experience. Too many boards lack directors with enough industry or relevant functional experience to be able to ask the right questions regarding strategy and performance. Consequently, boards are feeling growing pressure from regulators and shareholders to get serious about filling their experience and skill gaps and replacing directors who lack the energy, expertise or independence the role requires.

Again, this is an area where CEO influence has waned. CEOs still play an important role, suggesting and vetting candidates. But that role is informal; today, the nomination and selection process is owned by the board, and the change can be difficult for some CEOs. I personally observed the painful transition at a company where the CEO had handpicked the directors for 20 years. The directors finally found the courage to own the process when they rejected the CEO’s nomination of his next door neighbor (and, in years past, his children’s babysitter) to sit on their Fortune 500 board.

Trend #5: The Board is Taking Control of the CEO Succession Process

Probably the most visible shift in power from the CEO to the board involves CEO succession. Traditionally, the CEO (who was almost always a male) owned the process; he decided when the process should start, selected an heir apparent, and the board ratified his choice. The situation changed in 2009, when the Securities and Exchange Commission decided that CEO succession would no longer be considered a routine management decision; instead, shareholders suddenly won the right to ask questions about succession planning, and to hold the board—not the CEO—responsible for ensuring an adequate process was in place.

Today, the board is universally acknowledged as the owner of the succession process at public companies; how proactively and aggressively the board pursues that role varies dramatically from one company to the next. The CEO and his or her staff are still responsible for managing and implementing the process—taking the lead in identifying, assessing and developing candidates. But in most cases, the board has become much more involved at critical steps, culminating in the formal selection of the next CEO.

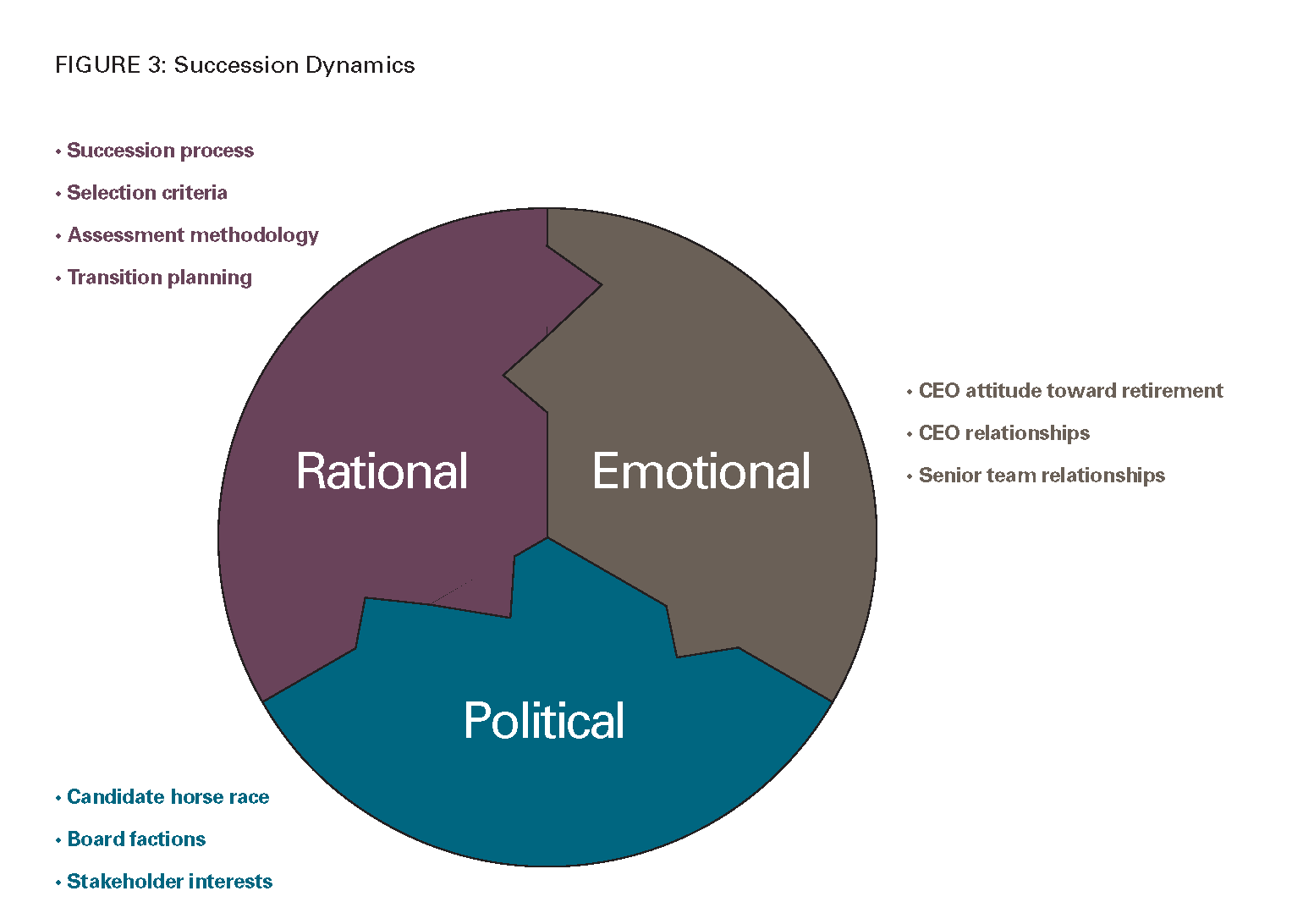

Here’s where it gets sticky. In human—rather than legal—terms, CEO succession is among the most difficult, complicated experiences any company can go through. As illustrated in Figure 3, it involves a complex web of dynamics involving rational processes, political conflict and personal emotions.

These forces collide, for example, when the succession process launches a competitive “horse race” that pits potential candidates against each other. Senior managers often become preoccupied thinking about the impact on their own careers; people start handicapping the race, taking sides and attributing business decisions to political motives—in short, the potential for dysfunction is enormous.

All three dynamics come together for CEOs, who must discourage the political activity and manage the formal succession process while coping with their own emotions, as well as those of the senior team. The saving grace for some CEOs in the past was that, as difficult as the situation might be, at least they were in the driver’s seat. No more. Now, the board is playing a major role in determining the timing, conduct and outcome of the process.

Depending on a manager’s role in the succession drama, the impact of this trend will vary. The change is likely to mean more transparency around the assessment and development process, and more exposure to the board for likely candidates. In many cases, it will also mean that a candidate’s personal relationship with the CEO will likely play a much less influential role than in the past.

Trend #6: The Board (and Management) are Deeply Concerned about Shareholder Activists

The final trend involves the most significant development in corporate governance in recent years: the sharp rise in shareholder activism. The practice of shareholders demanding changes in companies’ leadership, capital allocation, portfolio of businesses and returns to shareholders is nothing new; it’s been going on for almost 100 years. What is new is the emerging alliance between two forces: the relatively small investors and hedge funds, who typically launch activist campaigns; and the enormous institutional investors—the huge pension funds, giant insurers and large money managers like BlackRock—who control the majority of public shares.

Today, no public company is immune from activist shareholders. Even corporate behemoths like Apple, GM and United Airlines have been targeted by recent activist campaigns. There were about 360 publicly disclosed campaigns last year, and many more played out behind closed doors. In all, about 40 percent of the Fortune 500 companies were targets between 2009 and 2015 and there were consequences. McKinsey reports that over the past five years, 30 percent of activist campaigns resulted in a change in the company’s top management, and 34 percent resulted in the removal and replacement of board members.

Consequently, boards know they must become proactive by anticipating activists’ questions about the company’s structure, strategy, management, profitability, and returns to shareholders. The result of activist shareholders will be activist boards that aggressively scrutinize management performance through the eyes of the shareholders. They will demand more and better information, and insist that management consider more options for creating shareholder value: selling businesses, shutting operations, and increasing shareholder dividends at the expense of investing in the business. It remains to be seen how boards will balance short term versus long term value and, in the process, how they will adopt a consistently aggressive stance without creating a perpetually antagonistic relationship with management.

The Common Theme: Coping With Uncertainty

As if these six trends weren’t enough, we should also factor in the impact of relentless regulatory oversight. I would have included that as a seventh trend, except that it varies so dramatically across industries. In some banking firms, for instance, boards struggle with finding time to talk about business and strategy because their agendas are so dominated by regulatory and compliance matters.

Amid this unprecedented turbulence in corporate governance, here are some of the key implications for top managers.

- Assume that your level of contact with the board will change. The pressure on boards to exert tougher oversight, along with the growing presence of directors nominated by investor and shareholder groups, suggests that public company boards might begin acting more like private equity boards—more engaged between formal meetings, more apt to scrutinize business metrics, more likely to seek that information directly from managers. Some of the customary rules of engagement between managers and the board are being reconsidered in real time; don’t jump to conclusions about what’s allowed and what isn’t.

- The board’s changing composition will require directors to step up their performance in the board room beyond well-rehearsed “dog and pony shows.” As more directors with relevant experience join the board, expect sharper questions and direct challenge, and assume you’re in the room to amplify rather than provide a dramatic reading of the pre-meeting materials provided to the board.

- These trends will test each manager’s political skills in navigating an increasingly complicated relationship with both the CEO and the board. Beyond requests for specific data, some directors will pose questions regarding the CEO’s performance, senior team morale and other potentially incendiary topics. These situations require managers to have a clear sense of their own role and of where their loyalties lie. If there aren’t already some helpful ground rules in place within your management team, there should be.

A Final Note

As a former boss of mine used to say, in situations where the rules are changing, “assume positive intent.” Keep in mind that the overall intent of the governance changes are, indeed beneficial. Companies really do perform better when boards are actively, appropriately engaged with management. The trick is figuring out what that looks like at each organization.

Print

Print