Yannick Ouaknine is a senior analyst with the Socially Responsible Investing group at Société Générale S.A. The following post is based on an SG publication by Mr. Ouaknine, Daniel Fermon, Nimit Agarwal, Carole Crozat, and Niamh Whooley. This post relates to an SG publication titled “CEO Value,” issued June 6, 2016, available here.

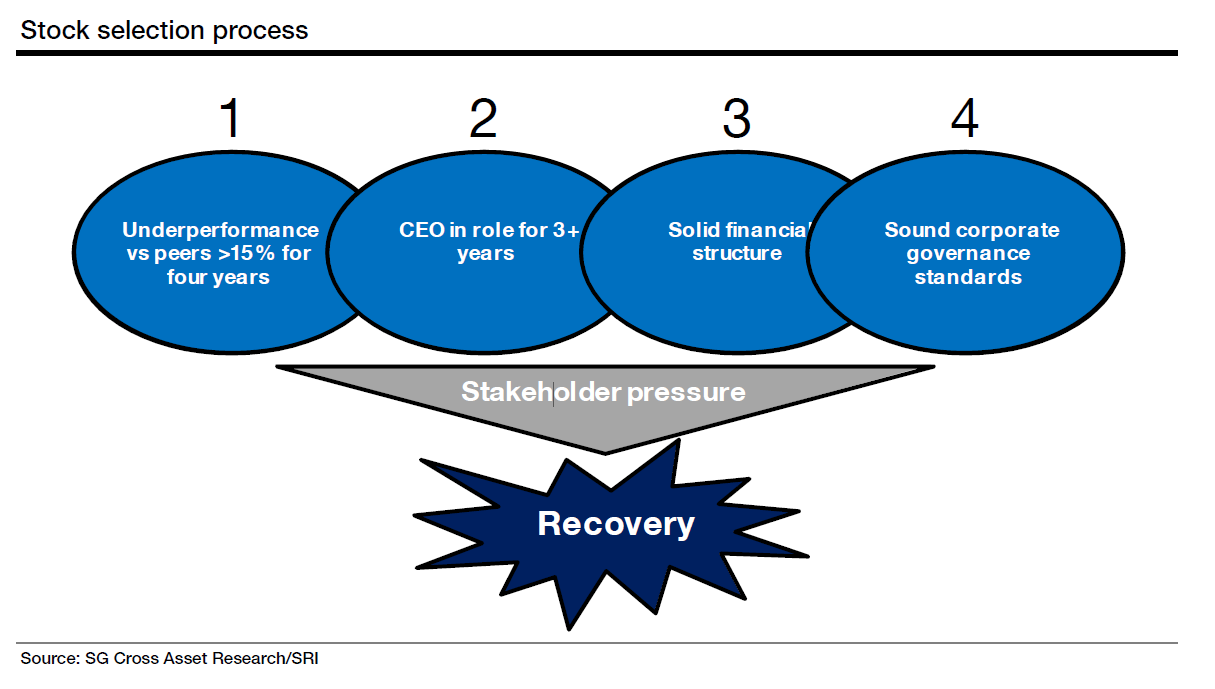

Our CEO Value stock selection process makes a simple assumption: a company that has relatively sound corporate governance principles but that has underperformed peers over four years should see a turnaround in its share performance. Sound corporate governance principles should enable a company to fix weakness or at least prevent deterioration either by changing its strategy or management—or both.

We look for stocks that have the following characteristics: 1) underperformed peers by at least 15% over the past four years; 2) not changed CEO for the last three years—the time needed to implement a strategy and reap the rewards; 3) a ‘solid’ financial structure; and decisively, 4) ‘sound’ corporate governance standards.

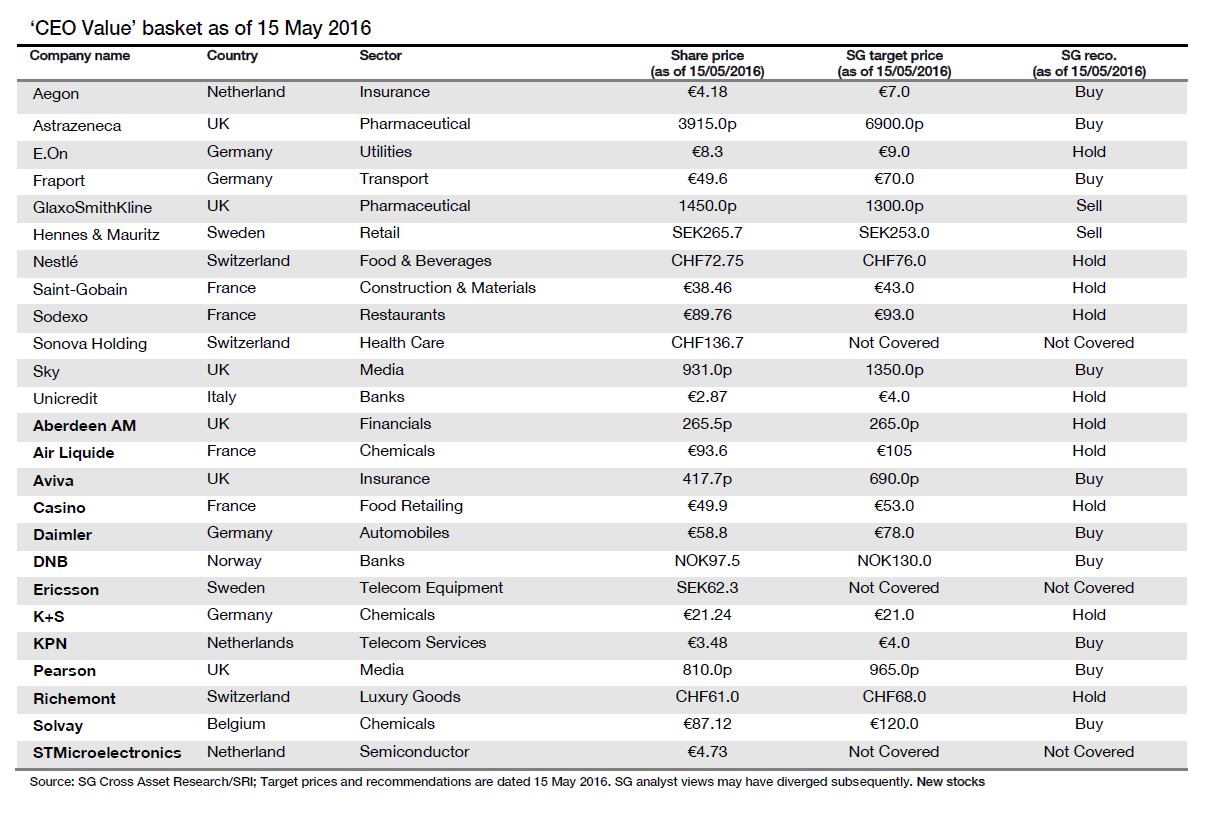

This post updates our CEO Value stock selection. We are replacing 13 stocks (out of 25) that no longer fit our selection criteria. The new entrants are: Aberdeen AM, Air Liquide, Aviva, Casino, Daimler, DNB, Ericsson, K+S, KPN, Pearson, Richemont, Solvay and STMicroelectronics.

Basket rebalancing—13 stocks in, 13 out

We are replacing 13 stocks out of 25 that no longer fit our selection criteria, as listed below. Consistent with the principles underlying our portfolio, the stocks we are replacing are either no longer underperforming their sector or have shown deteriorating financial and/or corporate governance fundamentals.

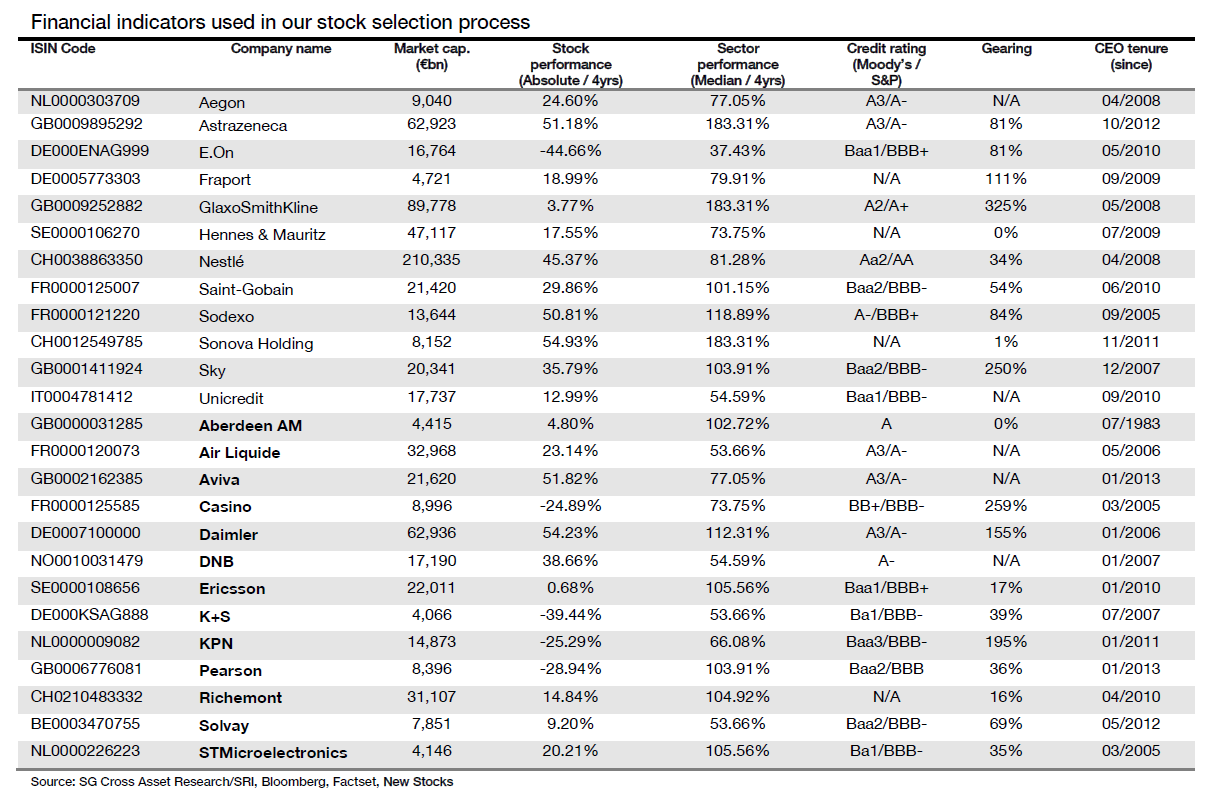

The 13 stocks we are adding have underperformed their sector by 15% or more over the past four years, have had the same CEO in place for more than three years, have a solid financial structure (based on fundamentals), and have sound corporate governance based on our own proprietary measures.

The new entrants are Aberdeen AM, Air Liquide, Aviva, Casino, Daimler, DNB, Ericsson, K+S, KPN, Pearson, Richemont, Solvay and ST Microelectronics.

The CEO Value stock selection process

An efficient four-step stock selection process combining a quantitative approach with a qualitative overlay

Underpinning our CEO Value stock selection is the idea that companies that have relatively sound corporate governance principles but which have underperformed over the previous four years should see an improvement in their share performance, either via a change of situation or a change of management. We described our selection process in detail, especially as regards relevant corporate governance principles, in our report “CEO Value and Corporate Governance stock list—Finding a way to performance…” (October 2008).

Criteria used to select our basket

Our CEO Value screening tool (launched in April 2006) is built using a bottom-up approach. We apply this screening tool to the Stoxx 600 index to obtain a list of European companies that we expect can deliver a “positive” message to investors over the following two years and which are thereby likely to outperform—and in this we also have a clear large cap bias. To be included in our list, stocks have to meet the following criteria:

- Underperformance of >15% relative to their sector over four years (approx. 150 stocks).

- CEO in office for more than three years (or less than one year); we consider this to be the time needed to implement a strategy effectively (approx. 80 stocks).

- A “solid” financial structure (as measured by the company’s credit rating, liquidity, gearing ratio… and a qualitative stock analysis) (approx. 60 stocks).

- “Sound” corporate governance standards (measured by a combination of quantitative and qualitative corporate governance on data ranging from “level of board independence”, to “remuneration”, to our “ESG controversies analysis” (25 stocks).

Our strategy is not without risk

The idea is to select companies that will implement change and move from being underperformers to outperformers. We identify two possible risks in our approach: 1) there is no change, or 2) changes take place, in management for instance, but the company’s situation continues to deteriorate.

Poor performance and CEO dismissals go hand in hand…

s highlighted in its most recent survey (“2015 CEO Success Study”—April 2016), Strategy&, which has been monitoring CEO turnover for more than ten years, has seen a growing correlation between poor short-term shareholder returns and CEO turnover. Furthermore, Strategy& finds that companies that have been experiencing poor returns work harder to ensure they hire or promote the “right” leader (as illustrated in our report “Beyond the Hype—Turning succession into success in the Luxury sector”—February 2015).

… but not all changes are for the better

Our report “CEO Value & Corporate Governance: pressure on management leading to improved stock performance” (June 2007) shows the results of our statistical analysis of ‘the new CEO effect’, and was computed without the addition of additional stock filters at that time (2003-

2006). This study outlines the justification for our investment strategy. We found that:

- On average, a recovery story ensued after the arrival of a new CEO, with the stock catching

up with the performance of its sector. - In the year after the appointment, these stocks outperformed their peers by 0.9% on average (against an average underperformance of 6.4% per year over the prior 3 years).

- However, we also noted that almost half the stocks continued to underperform peers that

same year.

“Sound” corporate governance is our guide to outperformance

In order to improve on this outcome, we therefore added several additional stock filters all related to criteria that identify stocks with good corporate governance. The observed improved performance of our CEO Value basket of stocks using the additional filter based on good corporate governance principles demonstrates, in our view, that “sound” corporate governance does provide a way to mitigate the risk in this kind of investment strategy.

Long investment horizon…

Our work shows that rising pressure on management from all stakeholders (including political and regulatory pressure) can lead to a clear improvement in share performance, but this tends to happen over the longer term, as financial recovery is the first goal. We believe there are two ideal periods for CEO-driven stock selection: first when stakeholder pressure is building, and second following the announcement of a CEO’s departure, when share prices typically dip or pause.

How do we define “sound” corporate governance?

Corporate governance evaluation—how it works

We highlight below some of the key corporate governance metrics that could trigger a business strategy and ultimately the financial performance of a company. To complete this view, some objective elements need to be added based on the intuitu personae and the momentum, but at this stage we recommend evaluating four “core” corporate governance angles:

1) The Board’s independence of judgment regarding the CEO’s vision

First we assess a board’s independence of judgment regarding the CEO’s vision, which is to say, the board of directors’ independence of judgment and ability to question and challenge (and even dismiss) the CEO if necessary. We define board independence using the following criteria:

- Composition of the board: In a two-tier board structure a supervisory board, essentially composed of non executives, oversees the functioning the executive management board. The composition of a board depends on the business profile and needs of the company. The selection process for non-executive board members involves filters like merit, professional qualifications, experience, personal traits and independence with a particular stress on diversity.

- Separation of chairman and CEO functions: This not only makes it easier to question the CEO’s strategy but also limits concern over the balance of power and lowers the risk linked to the departure of a single person who holds both positions. The percentage of the incoming classes of CEOs that has involved the appointment of a joint CEO/chairman has steadily decreased since 2000, reaching an all-time low in 2013, with an average of 9% vs 14% in 2011, 18% in 2008 and 48% in 2002 (Source: Strategy&).

- Other corporate affiliations: The CEO is the highest-ranked executive in the company and is answerable to the board. Given this is a critical position, it is generally good policy to ensure the CEO focuses exclusively on running the business and does not get sidetracked by other ancillary interests.

- Independence of non-executive directors: In addition to the various links that directors can have with a company, which raises the question as to the directors’ actual independence, tenures of more than 12 years are commonly considered inconsistent with genuine independence.

- Professional diversity: Diversity of professional backgrounds and experience should result in superior decision-making through a better understanding of the various impacts of a decision on a company’s markets, its financial performance or its stakeholders, whether employees, customers, suppliers or regulators.

- International diversity: For a company with exposure to international markets, as is the case with most large companies, having non-nationals on the board makes a lot of sense, as it adds knowledge and experience from diverse origins and backgrounds.

- Gender diversity: The proportion of women on the board of listed companies in the European Union is only 25% (as per European Commission findings). Positively, women are found to have different leadership styles, attend more board meetings and have a positive impact on the collective intelligence of a group, all of which would suggest a positive correlation between the percentage of women on the board and corporate performance.

- Proportion of non-executive directors: We positively view a high proportion of nonexecutive directors on the board, as executive directors may be overly dependent on the CEO.

- CEO’s role in the nomination process: We like company policies where the CEO does not sit on the nomination committee and has no role in appointing non-executive or supervisory directors. Board members appointed by the CEO who enjoy substantial pay and prestige because of their position may be less likely to challenge management actions and decisions, particularly in trying times.

2) Board and shareholding structures

We also identify a second set of criteria, related to the board as well as shareholding and voting rights structures:

- Shareholding structure: A higher free float makes for a diverse shareholding structure and (potentially) a meaningful engagement of shareholders at the AGMs. Family ownership can have both positive and negative outcomes, positive through direct oversight and negative by exerting excessive influence.

- Share capital ownership and control: We are in favour of the “one share-one vote-one dividend” principle. Multiple-class shares confer voting rights that are disproportionate to ownership levels, thus potentially penalizing minority shareholders.

- AGM agenda & results: The AGM is the platform for shareholders to agree or oppose the agenda proposed by the board. It is also a forum for shareholders to understand the company’s management strategy and direction of business and ask questions. An AGM with a high proportion of shareholder votes against the items on the agenda may highlight views that diverge from the board’s proposals/strategy. In recent proxy seasons, one of the agenda items that has attracted the most debate is “executive remuneration”.

- Reference shareholder: Firms tend to be sensitive to investor preoccupations when a portion of their shares are held by active shareholders.

- Medium- or small-sized boards: Large boards are considered less effective than small boards as agency problems tend to increase when boards become oversized. The stewardship role of the board therefore becomes more symbolic and the board can be more prone to display weaker monitoring and controlling of managerial decisions.

- Business ethics-related controversies: These controversies may arise when management or employees commit unethical actions like participation in bribery or accounting fraud. Those unethical business actions not only impact the company financially, raising questions about its internal controls, but also creates reputational risk. Therefore, analysing these issues is a good complement to the other analysis criteria.

3) Compensation schemes linked to shareholder returns

We consider this third criterion to be one of the most sensitive corporate governance issues in the current economic environment, attracting considerable public, investor and political attention. Share ownership is supposed to align directors’ interests with those of shareholders. There has been growing pressure to increase the link between executive pay and shareholder returns; several regulations put in place throughout Europe establish a link between severance packages and company performance.

- Directors’ remuneration policy: Directors’ remuneration can be seen as a way to align the interests of shareholders with those of the executive directors. Poor remuneration policy disclosure may give rise to questions on the transfer of value from the company to executives. Also a short-term focus on performance may have an impact on long-term objectives. It is important for the variable remuneration of executive directors to be intrinsically linked to their performance and responsibilities. Various action points in this respect include adequate disclosure of remuneration policy of executive and non-executive directors, disclosure of their remuneration, and a shareholder resolution on remuneration policy. Finally, the remuneration committee should be fully independent with greater autonomy given to non-executive directors in setting up the remuneration policy.

- Remuneration structure: We are in favour of a good balance between short-, medium- and long-term incentives. The variable component should incentivise long-term performance but also have a claw-back clause for accountability for past actions (i.e. corporate fraud). The policy should have a transparent structure, be backed with quantitative indicators and be available for shareholder perusal.

4) Succession planning/CEO tenure

This is the fourth criterion we use to analyse corporate governance. One reason why boards may act slowly when it comes to replacing a CEO is often due to a lack of anticipation and a failure to identify and select qualified candidates well in advance.

- Succession planning structures and schemes: Being proactive allows companies to build

a pool of candidates for key functions within the organisation. - CEO tenure: The longer the tenure of the CEO in a company the better from an oversight or management view point. However, a long tenure also emphasises the need for proper succession planning. A departing CEO takes a lot of management expertise away from the company, so it is important to create a pool of candidates with the ability to drive business momentum in the same direction as in the past.

Note that all of the above criteria should be examined when evaluating corporate governance standards and that it is important to consider qualitative factors (corporate governance analysis is not a “box ticking” exercise!).

From theory to practice: We analyse corporate governance at two levels

We cannot make all of the above criteria mandatory in our stock selection, as our pool of possible stocks would be reduced to close to zero. Instead, we use two levels of corporate governance analysis as an additional filter.

- First, we collect corporate governance data under ‘core’ categories to determine which companies match basic corporate governance best-practice standards in terms of: 1) shareholders, 2) CEO, 3) independence, 4) committees, and 5) remuneration; and then we screen for the following additional categories: 6) diversity, 7) ESG controversies, 8) other policies, and 9) corporate social responsibility (CSR).

- Second, we gauge the views of our equity analysts on corporate governance standards in their sectors.

Using both levels of analysis, we exclude groups that have a poor corporate governance evaluation, i.e. below-sector practices and/or a poor governance perception as provided by analysts.

Bottom line: this is not a “best-in-class” approach

Our screening methodology is not based on a classic “best-in-class” analysis that picks exclusively the best-rated companies on corporate governance in a sector. As we apply multiple filters—in particular the selection of companies that have underperformed their peers over the last four years—our pool of possible stocks is not therefore representative of a best-in-class basket.

“CEO Value” portfolio update

Our “CEO Value” strategy consists of drawing up a list of stocks for which corporate governance principles could be expected to drive improved financial performance. Our selection of ‘CEO Value’ stocks has outperformed its benchmark since launch. In the complete publication, we rebalance our selection, replacing 13 stocks that have either recovered or experienced a negative change in terms of financial and/or corporate governance structure.

Our basket’s features

- Each stock in our selection list is equally weighted.

- When rebalancing the list, we equally weight each stock again.

- Our portfolio selection criteria make no allowance for any balance across sectors or countries; the selection process is based purely on individual stock performance and corporate governance criteria.

- Our “CEO Value” list was first created on 4 April 2006 and has since been rebalanced 13 times (13/06/2007, 29/02/2008, 02/11/2008, 19/08/2009, 03/05/2011, 10/05/2012, 27/05/13, 27/12/2013, 31/05/2014, 01/12/2014, 18/05/2015, 20/11/2015 and finally 15/05/2016).

Stock selection rationale

Our stock selection is based on the potential catalysts for an upswing in performance over the next few years, as identified by our screening model. When relevant, we might add sector-specific metrics (i.e. “Core Tier 1 capital” for the banks).

Company “corporate governance” assessment

Finally we undertake a detailed analysis of the corporate governance criteria used to create our CEO Value basket.

This summarises “Global performance in Corporate Governance” across four categories based on criteria for: 1) shareholders, 2) directors, 3) ESG controversies, and 4) codes, policies and CSR, AND two last criteria for what call “room for improvement’ and ‘good standards.”

The complete publication is available here.

Print

Print