Ronald J. Gilson is Marc & Eva Stern Professor of Law and Business at Columbia Law School, Meyers Professor of Law and Business (Emeritus) at Stanford Law School, and a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Hans Weemaes is a principal at Cornerstone Research. This post is based on a Cornerstone Research publication by Professor Gilson, Mr. Weemaes, Ilene Friedland, and Cameron Hooper.

Corporate governance issues often figure prominently in litigation, but the issues raised typically have a narrow focus. Disputes most often build on the formal legal skeleton of corporate governance created by the state’s corporation’s statutes, the particular corporation’s organizational documents, and the judicially imposed fiduciary duty of directors and officers. However, this structure represents an overly formal and significantly incomplete understanding of what makes up a publicly held corporation’s corporate governance structure. In this article, we outline the much broader corporate governance structure that underlies the operation of a modern public corporation, and show how that structure has important implications for a wider range of litigation than is commonly understood.

What is Corporate Governance?

The basic shape of a corporation’s governance structure is provided by the formal legal skeleton. Indeed, this formal structure addresses a set of high-profile matters, including the allocation of decision-making rights (and, hence, the influence over corporate control) among the board of directors, senior management, and shareholders. However, this structure accounts for only a relatively small part of how the corporation actually carries out its business and how it adapts to its business environment. The rest of the governance structure—what we might call the “dark matter” of corporate governance—lies in the realm of reporting relationships, organizational charts, internal controls, risk management, and information gathering. These are non-legally-dictated policies, practices, and procedures that do not appear in the corporate statute or the corporation’s charter or bylaws. Put differently, corporate governance is the corporation’s operating system.

Specifically, corporate governance encompasses how the corporation:

- Obtains the information it uses in making, implementing, and monitoring the results of its business decisions, including decisions concerning how best to conduct the company’s business and decisions relating to its efforts to comply with applicable regulation;

- Causes that information to move up the corporate hierarchy from where it originates to those in management who have the expertise and experience to evaluate that information; and

- Makes, communicates, and monitors the implementation of the decisions arrived at based on that information.

Since each company has a different governance structure, the totality of the corporate governance structure must be understood before analyzing an individual or specific governance issue.

Corporate Governance in Litigation

When viewed more broadly as a corporation’s operating system, corporate governance has implications not only for litigation that typically arises in connection with contests over corporate control and with claims of fiduciary duty breach, but also for operational matters, including those related to materiality and scienter issues.

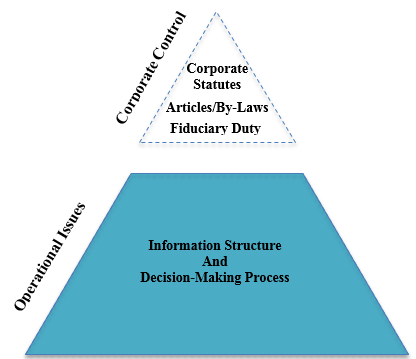

As Figure 1 illustrates, this broader view of corporate governance figures prominently when the litigation calls into question the character of a corporate decision, for example, a decision concerning disclosure under the securities laws or the “state of mind” of a corporation charged with violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). A corporate governance perspective may also be relevant in analyzing product liability issues or mutual fund excessive fee claims. Thus, a corporate governance analysis can be useful in addressing allegations related to bribery, fraud, and reckless conduct in whatever legal context those issues are raised.

For instance, a common pattern in securities fraud class actions is for plaintiffs to identify a “smoking gun”—for example, an e-mail written by a lower-level employee such as a sales manager containing apocalyptic statements about what the employee thinks is happening to the company’s business. Plaintiffs typically claim that had the information contained in the e-mail been disclosed at that time, the company’s stock price would have fallen before the plaintiffs purchased the stock.

Figure 1: Corporate Governance Litigation Pyramid

A common approach to assessing the consequences of the alleged undisclosed or improperly disclosed information is to employ a statistical analysis to determine whether a particular disclosure is associated with a significant change in the total mix of information—often measured by conducting an event study. In contrast, a governance approach to assessing the consequences of the “smoking gun” claims is to examine the company’s corporate governance system.

As discussed above, a corporate governance system can be conceived as an information flow and a decision-making process by which information moves from the operating level up through the managerial hierarchy to where decisions are made. Understanding the system of information flows (including reporting mechanisms) and decision-making structures (such as committees) allows isolated pieces of information to be considered in their proper context. For instance, an analysis of the company’s corporate governance system (including a review of memos, minutes, and other e-mails) might reveal that the information in the “smoking gun” e-mail did in fact work its way up the corporate hierarchy to the level where assessments concerning the corporation’s operating strategies and projections are made. This analysis, along with an open mechanism for allowing lower-level employees to air concerns or grievances, can provide evidence that such concerns were reported and assessed.

These assessments provide the basis for the corporation’s disclosure decisions. A corporation’s governance structure locates the decision about what is material—to the corporation’s business decisions and its disclosure obligations—at the senior management level where the information (and the buck) stops. The decision maker satisfies both her obligations and those of the corporation under corporate and securities law by making this decision in good faith and not recklessly.

In this sense, the information portrayed as a smoking gun can be addressed by the fact that the decision makers had the information at issue and addressed it. A case can therefore be defended by analyzing the operational system of a corporation and placing the “smoking gun” information in its proper context. This type of analysis involves an investigation into:

- Where the information originated;

- How and where the information was disseminated;

- Who recognized and reviewed the information;

- Whether the flow of information was consistent with company policies;

- In what form the information arrived at the relevant decision makers within the governance structure; and

- Whether the decision was made according to the standard of care that would normally apply to the individual(s) in that position.

These represent just some of the considerations that are relevant when addressing the “smoking gun” claims.

Another claim that plaintiffs frequently make in securities fraud class actions is that company managers caused the company to issue false financial statements. Again, the alleged actions of the defendants can be addressed by analyzing the company’s corporate governance system. Management is obligated to have a system in place that provides reasonable assurance that reliable information—information that management can confidently rely on to make business decisions and to comply with financial reporting requirements—is generated at the appropriate place in the governance structure. The alleged actions of the defendant cannot be considered in isolation; they should be assessed with an appreciation of the company’s operating environment. Whether a standard of care has been met will depend on the decision and information structure of the company. Information related to the alleged omission or misleading statement can be traced throughout the company’s operational system and placed in the proper context of the company’s structure, policies, practices, and procedures.

Corporate governance issues are often intertwined with other allegations and thus might initially be overlooked. For example, in litigation related to allegations of accounting misconduct, issues surrounding company processes (such as certification and disclosure processes) may provide important contexts. Similarly, in consumer product failure cases issues of product evaluation processes and testing procedures, as well as the information and decision-making structure through which product decisions are made, may be relevant to responding to the claims and defenses in the litigation.

Corporate Governance Experts Provide Context

The goal of a corporate governance expert is to address the alleged conduct in the proper context of the company’s operating environment and in terms that jurors can relate to the collective experience. Most jurors have had little experience with how a company operates. For them the issue is how the “company” acted. For example, did the company act in a “reckless” manner? Without guidance, they may be unaware that the company can act only through its employees and executives, who in turn act through the company’s governance process. That process determines how the company obtains the information needed to run its business and comply with applicable regulatory requirements, how this information gets to the right decision makers, and how the ensuing decisions are implemented and monitored.

One role of a corporate governance expert thus may be to evaluate how information is collected and disseminated through a specific company’s reporting and information systems. The expert may also evaluate how these systems supported the decisions and judgments at issue in the litigation in the proper context of the information that was available at the time. For example, the expert may opine on the reasonableness of the company’s process in support of management’s certification of its financial statements. The expert might proceed by analyzing how information about the design, implementation, and results of the certification process was collected and disseminated throughout the company’s reporting and information systems and how these systems supported the certification.

Similarly, in an FCPA case, a corporate governance expert may be called upon to examine a company’s policies, procedures, and structures in order to ensure compliance with FCPA laws and regulations. In this context, the expert can assess whether the process caused relevant decisions to be made at a level where information, expertise, and access to professional advice coincided. The expert may also evaluate the activities of directors, officers, managers, and their advisors to determine whether they acted in a manner consistent with the company’s FCPA compliance structure.

This type of analysis is frequently relevant to a broad range of issues and thus the work of a corporate governance expert can often provide a foundation for the work of other experts. For example, in a Rule 10b-5 case, identification of the appropriate class period requires determination of when the alleged stock inflation was first impounded into price. A corporate governance expert’s analysis of the company’s information and decision structures can help determine when the relevant information should have been disclosed to the public. The same inquiry can help the damages expert determine the period over which there are economic damages.

Conclusion

Corporate governance issues in litigation appear most clearly in cases raising issues of corporate control. These issues often require parsing the sometimes conflicting role of directors and shareholders in control contests that have been a familiar pattern for years and show no indication of slowing down. However, corporate control is only the visible tip of the corporate governance iceberg. Assessments of the corporation’s governance system can provide the context within which state of mind assessments, such as good faith and recklessness, are made. Issues such as these pervade a wide range of claims against corporations. A corporate governance expert can provide useful guidance in explaining how a corporation actually acts, assessing the quality of a corporation’s information and decision-making processes, and providing important context for the opinions of other experts.

Print

Print