Jay Bothwick and Hal Leibowitz are partners at Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr LLP. This post is based on a WilmerHale publication.

Market Review and Outlook

Review

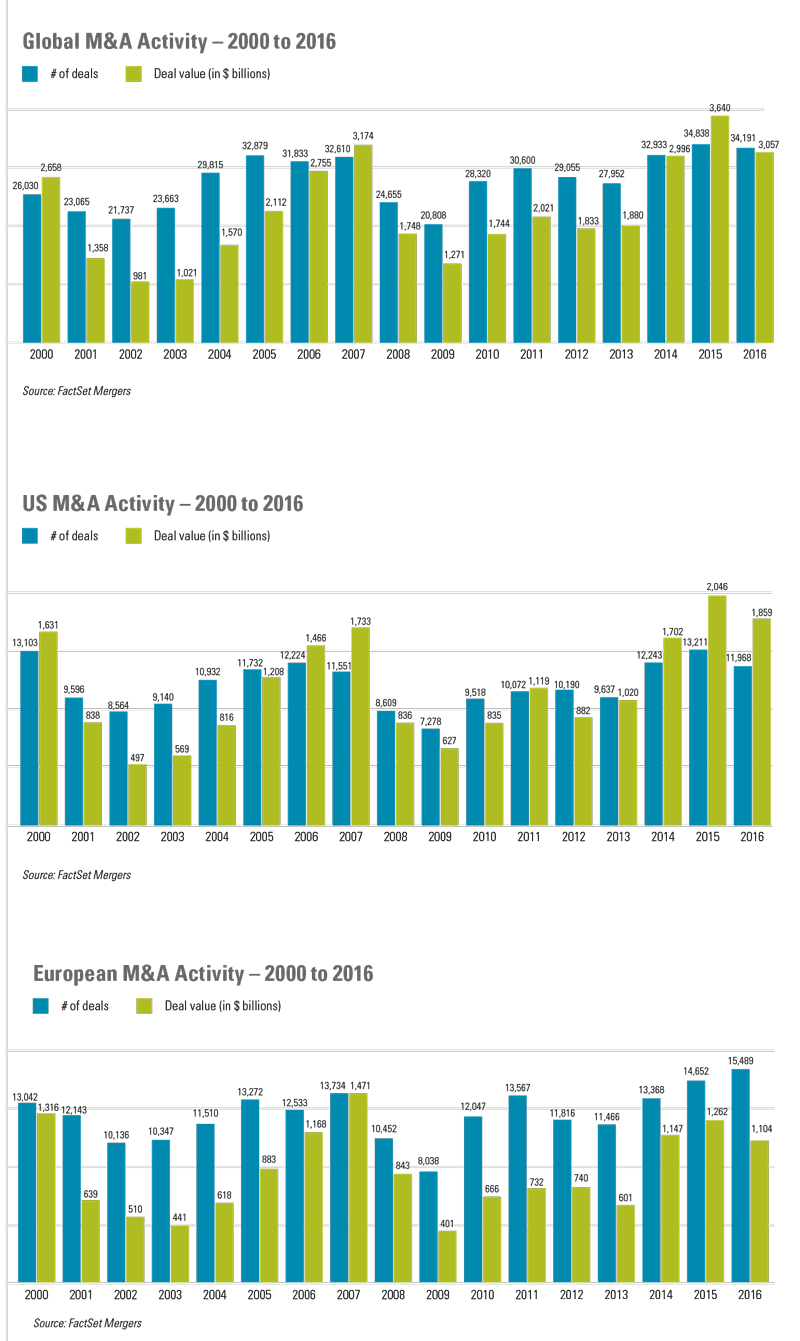

In 2016, the number of reported M&A transactions worldwide dipped by 2%, from a record 34,838 deals in 2015 to 34,191, but still represented the second-highest annual tally since 2000. Worldwide M&A deal value decreased 16%, from $3.64 trillion to $3.06 trillion—a total that was still the third-highest annual figure since 2000, lagging behind only 2015’s record tally and 2007’s $3.17 trillion result.

The average deal size in 2016 was $89.4 million, 14% below 2015’s average of $104.5 million, and just shy of 2014’s average of $91.0 million, but 40% above the annual average of $64.0 million for the five-year period preceding 2014.

The number of worldwide billion-dollar transactions decreased 9%, from 540 in 2015 to 489 in 2016. Aggregate worldwide billion-dollar deal value declined 21%, from $2.68 trillion to $2.11 trillion.

Geographic Results

Total deal value decreased across all geographic regions in 2016, with Europe the only region seeing an increase in the number of M&A transactions:

- United States: Deal volume decreased 9%, from 13,211 transactions in 2015 to 11,968 in 2016. US deal value declined by a similar percentage, from $2.05 trillion to $1.86 trillion. Average deal size inched up from $154.9 million in 2015 to $155.3 million in 2016—the highest average deal size in the United States since

- The number of billion-dollar transactions involving US companies decreased by eight, from 286 in 2015 to 278 in 2016, while the total value of these transactions decreased 11%, from $1.65 trillion to $1.47 trillion.

- Europe: Deal volume in Europe improved in 2016 for the third consecutive year. The number of transactions increased 6%, from 14,652 in 2015 to 15,489 in 2016—the European market’s high point since 2000. Total deal value decreased 12%, from $1.26 trillion to $1.10 trillion, contributing to a 17% decrease in average deal size from $86.1 million to $71.3 million. The 2016 figure was also well below the 2014 average of $85.8 million. The number of billion-dollar transactions involving European companies declined for the second consecutive year, from 180 in 2015 to 157 in 2016. The total value of billion-dollar transactions declined by 18%, from $952.5 billion in 2015 to $778.0 billion in 2016.

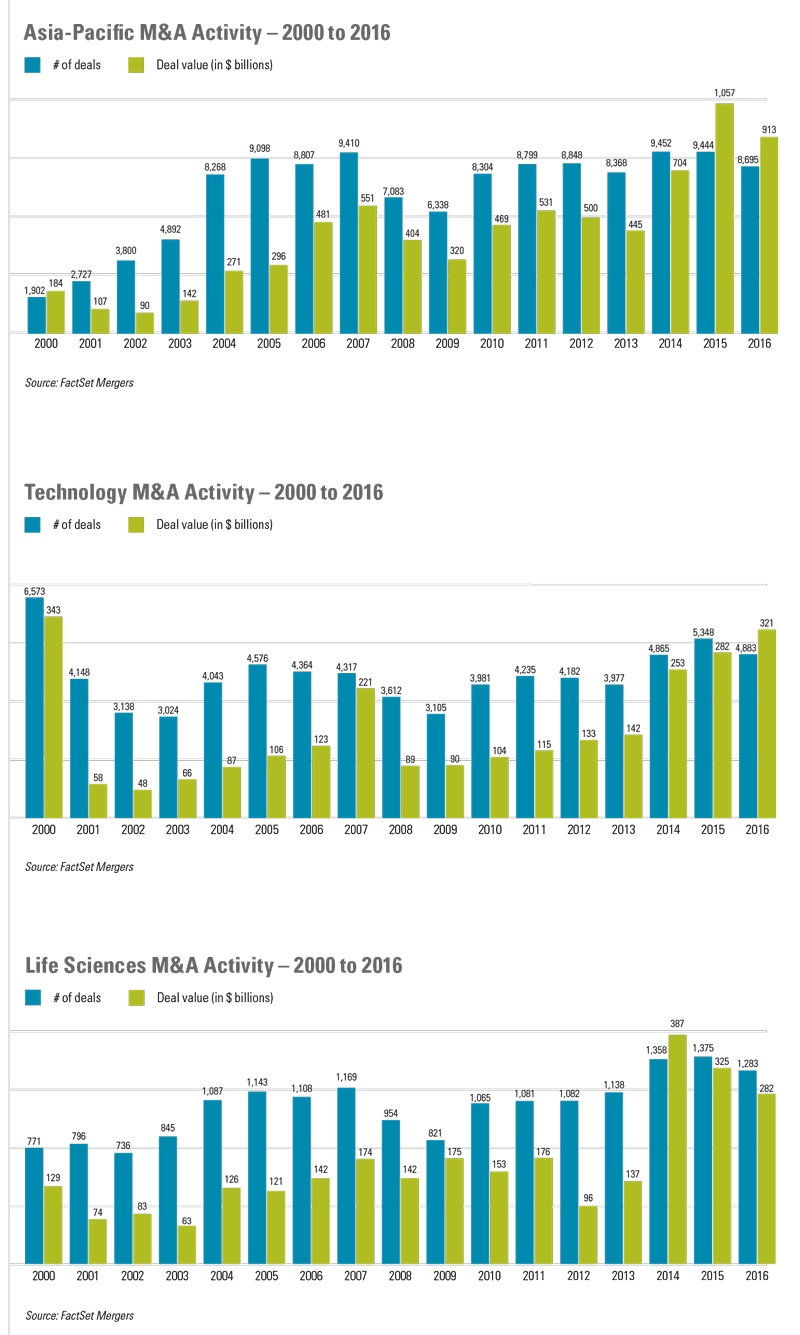

- Asia-Pacific: The Asia-Pacific region saw its second consecutive annual decline in deal volume, by 8%, from 9,444 transactions in 2015 to 8,695 in 2016. Total deal value in the region decreased 14%, from $1.06 trillion to $913.4 billion, resulting in a 6% decrease in average deal size, from $111.9 million to $105.1 million—still the second-highest total deal value and average deal size in the region since 2000. Billion-dollar transactions involving Asia-Pacific companies decreased 11%, from 190 to 170, while their total value declined by 18%, from $674.0 billion to $553.7 billion.

Trends in M&A deal volume and value varied across industries in 2016:

- Technology: Global transaction volume in the technology sector decreased 9%, from 5,348 deals in 2015 to 4,883 deals in 2016. Despite the decline, 2016 represented the second-highest annual tally since the 6,573 transactions in 2000. Global deal value increased 14%, from $281.8 billion to $321.1 billion—the eighth consecutive annual increase in deal value for this sector. Average deal size increased 25%, from $52.7 million in 2015 to $65.8 million in 2016. US technology deal volume decreased 17%, from 2,768 to 2,296. Total deal value in the United States followed the global trend, increasing 26%, from $171.2 billion to $215.7 billion. This jump in turn resulted in a 52% increase in average deal size, from $61.9 million to a record level of $93.9 million.

- Life Sciences: Global transaction volume in the life sciences sector decreased 7%, from 1,375 deals in 2015 to 1,283 deals in 2016, while global deal value decreased 13%, from $324.5 billion to $282.1 billion—the second consecutive annual decline in deal value. As a result, average deal size decreased 7%, from $236.0 million to $219.8 million. In the United States, deal volume declined by 6%, from 621 to 582. Total US deal value, however, increased 14%, from $204.0 billion to $231.8 billion, resulting in a 21% increase in average deal size, from $328.4 million to $398.3 million.

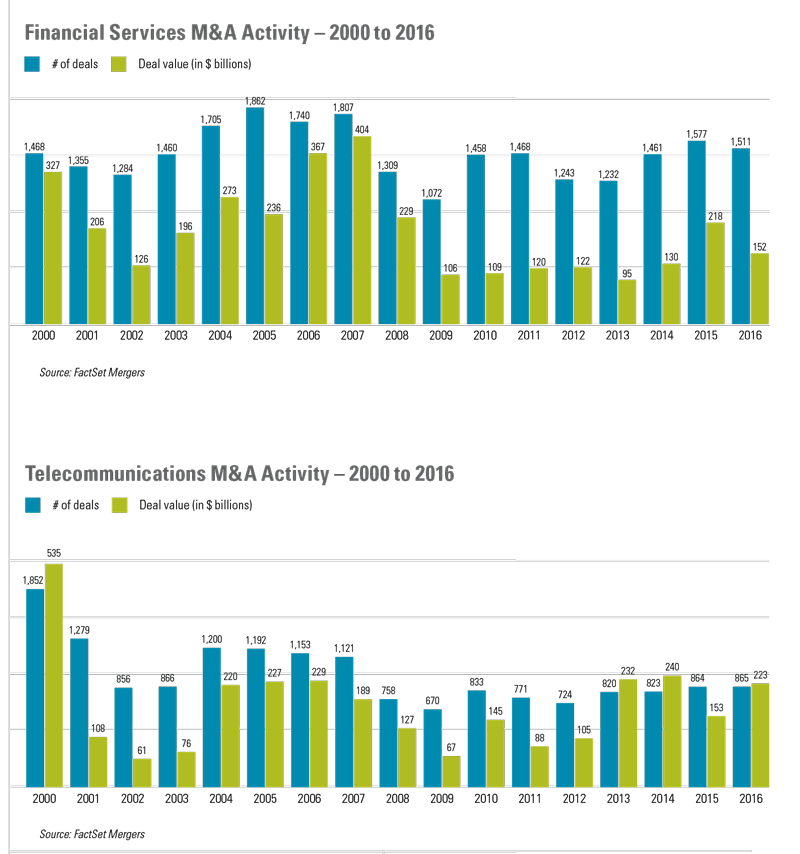

- Financial Services: Global M&A activity in the financial services sector decreased 4%, from 1,577 deals in 2015 to 1,511 deals in 2016. Despite the decline, 2016 yielded the second-highest annual tally since 2007, which marked the end of a four-year period that saw an annual average of 1,779 deals. Global deal value declined by 30%, from $217.7 billion to $152.1 billion, resulting in a 27% decline in average deal size, from $138.0 million to $100.7 million. In the United States, financial services sector deal volume decreased 9%, from 548 to 498, while total deal value declined by 43%, from $116.3 billion to $66.2 billion. Average deal size decreased 37%, from $212.2 million to $133.0 million.

- Telecommunications: Global transaction volume in the telecommunications sector inched up from 864 deals in 2015 to 865 deals in 2016—the fourth consecutive annual increase in deal volume. Global telecommunications deal value increased 45%, from $153.2 billion to $222.6 billion, a total that, when combined with flat deal volume, resulted in a corresponding 45% increase in average deal size, from $177.3 million to $257.3 million. US telecommunications deal volume increased 4%, from 282 to 294, while total deal value more than tripled, from $41.8 billion to $172.6 billion. The average US telecommunications deal size in 2016, at $587.1 million, was nearly four times the 2015 average of $148.3 million.

- VC-Backed Companies: The number of reported acquisitions of VC-backed companies increased 6%, from 531 in 2015 to 561 in 2016. Once all 2016 acquisitions are accounted for, 2016 deal activity should be in line with the total of 574 deals in 2014, but will likely fall short of the tallies of 608 and 589 in 2010 and 2011, respectively. Total deal value increased 42%, from $58.1 billion in 2015 to $82.4 billion in 2016, but was below 2014’s total deal value of $88.5 billion.

Outlook

Heading into 2017, macroeconomic uncertainty and high stock market valuations may create headwinds for the M&A market, despite high levels of cash held by both strategic and private equity acquirers, an uptick in inbound M&A activity, and the continued desire of many companies to pursue acquisitions to supplement organic growth. On balance, the M&A market remains fundamentally sound, and deal activity in 2017 should approach the aggregate deal volume and value of 2016. Important factors that will affect M&A activity in the coming year include the following:

- Macroeconomic Conditions: The US economy lost momentum over the last three months of 2016 and the year ended with an annual growth rate of 1.6%—its weakest performance in five years, while the global economy remains mired in the pattern of low growth that has persisted for a decade. Moreover, after raising its benchmark interest rate only once in the preceding decade, the Federal Reserve increased the rate in December 2016 and again in March 2017, and further rate hikes are widely expected in the coming year.

- Market Conditions: There is growing sentiment that US stocks might have reached their peak valuations in the first quarter of 2017. Record high stock market valuations may discourage buy-side activity by acquirers concerned about over-paying, while also making some sellers less willing to accept buyer stock as consideration because of perceptions of limited upside potential and significant downside risk.

- Private Equity Impact: On the buy side, private equity firms are sitting on record levels of “dry powder” to deploy, but the supply of capital is intensifying competition for attractive deals and driving up prices. On the sell side, private equity firms—having increased their fundraising for the fourth consecutive year—are facing pressure to exit investments and return capital to investors, even if investor returns are dampened by increases in the level of equity invested in deals.

- Venture Capital Pipeline: Many venturebacked companies and their investors prefer the relative ease and certainty of being acquired to the lengthier and more uncertain IPO process. Deal volume for sales of VC-backed companies will depend in part on the extent of the ongoing correction in private company valuations, as well as the health of the IPO market. Although the number of US venture-backed IPOs declined for the second consecutive year in 2016, their solid aftermarket performance is likely to generate demand for additional VC-backed IPOs in 2017.

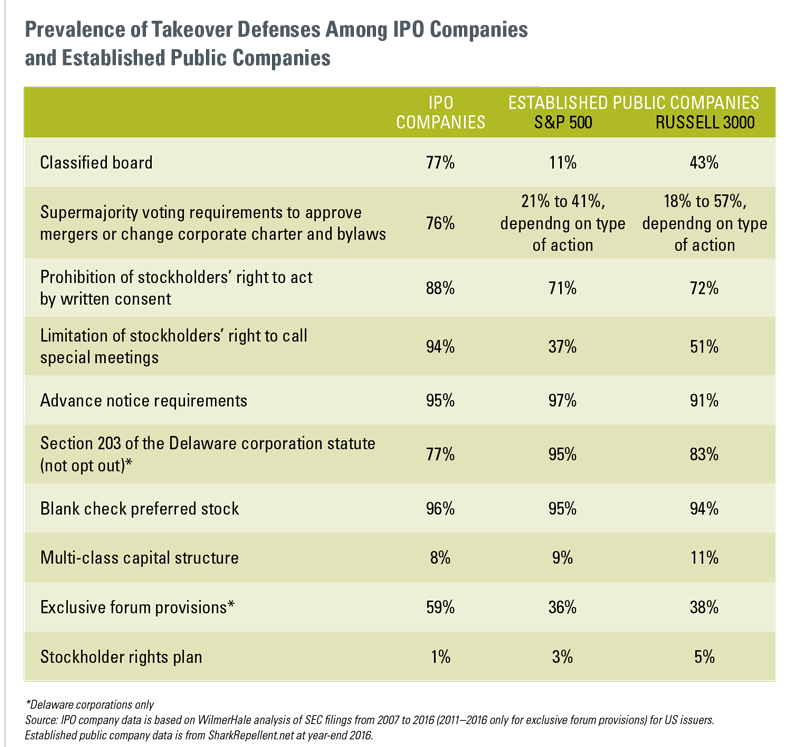

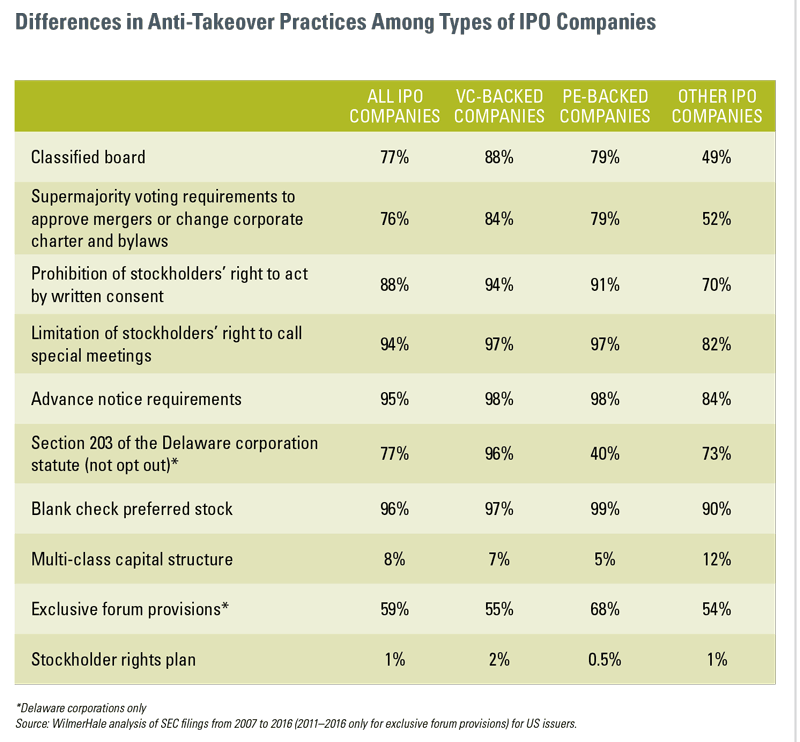

Takeover Defenses: An Update

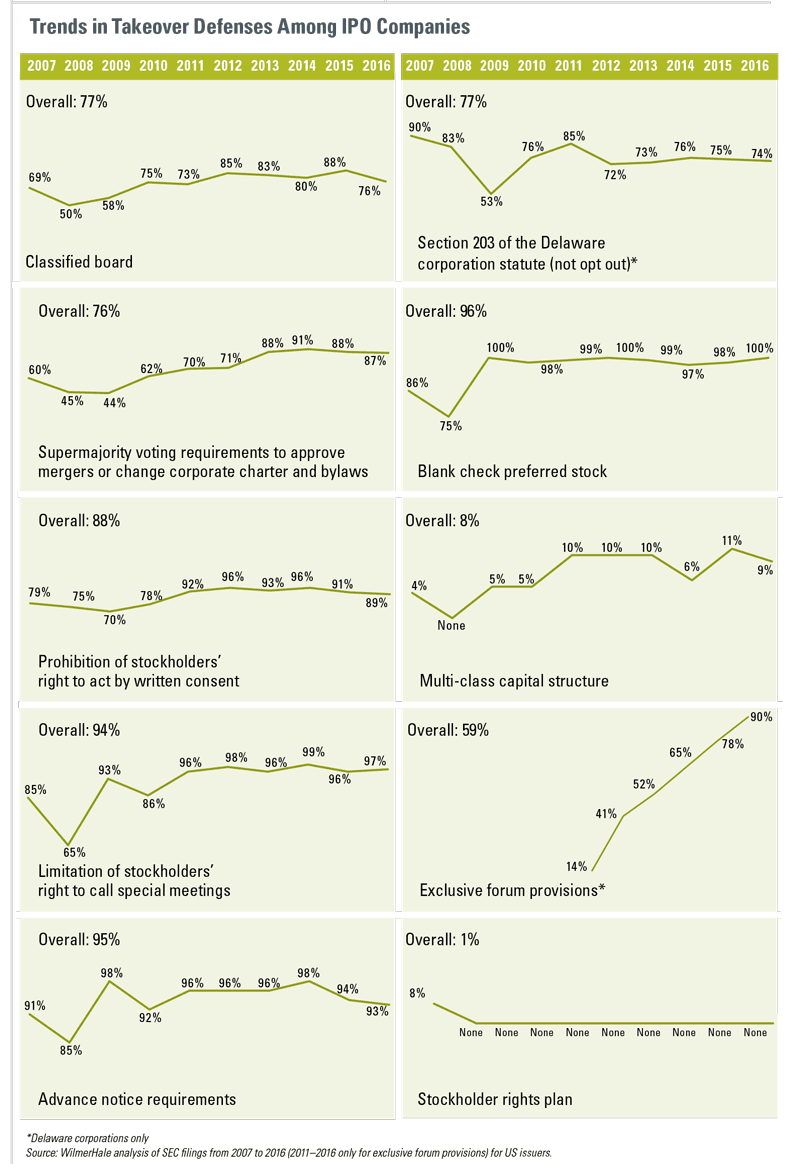

Set forth below is a summary of common takeover defenses available to public companies—both established public companies and IPO companies—and some of the questions to be considered by a board in evaluating these defenses.

Classified Boards

Should the entire board stand for reelection at each annual meeting, or should directors serve staggered three-year terms, with only one-third of the board standing for re-election each year?

Supporters of classified, or “staggered,” boards believe that classified boards enhance the knowledge, experience and expertise of boards by helping ensure that, at any given time, a majority of the directors will have experience and familiarity with the company’s business. These supporters believe classified boards promote continuity and stability, which in turn allow companies to focus on long-term strategic planning, ultimately leading to a better competitive position and maximizing stockholder value. Opponents of classified boards, on the other hand, believe that annual elections increase director accountability, which in turn improves director performance, and that classified boards entrench directors and foster insularity.

Supermajority Voting Requirements

What stockholder vote should be required to approve mergers or amend the corporate charter or bylaws: a majority or a “supermajority”?

Advocates for supermajority vote requirements claim that these provisions help preserve and maximize the value of the company for all stockholders by ensuring that important corporate actions are taken only when it is the clear will of the stockholders. Opponents, however, believe that majority-vote requirements make the company more accountable to stockholders by making it easier for stockholders to make changes in how the company is governed. Supermajority requirements are also viewed by their detractors as entrenchment provisions used to block initiatives that are supported by holders of a majority of the company’s stock but opposed by management and the board. In addition, opponents believe that supermajority requirements—which generally require votes of 60% to 80% of the total number of outstanding shares—can be almost impossible to satisfy because of abstentions, broker non-votes and voter apathy, thereby frustrating the will of stockholders.

Prohibition of Stockholders’ Right to Act by Written Consent

Should stockholders have the right to act by written consent without holding a stockholders’ meeting?

Written consents of stockholders can be an efficient means to obtain stockholder approvals without the need for convening a formal meeting, but can result in a single stockholder or small number of stockholders being able to take action without prior notice or any opportunity for other stockholders to be heard. If stockholders are not permitted to act by written consent, all stockholder action must be taken at a duly called stockholders’ meeting for which stockholders have been provided detailed information about the matters to be voted on, and at which there is an opportunity to ask questions about proposed business.

Limitation Of Stockholders’ Right To Call Special Meetings

Should stockholders have the right to call special meetings, or should they be required to wait until the next annual meeting of stockholders to present matters for action?

If stockholders have the right to call special meetings of stockholders, one or a few stockholders may be able to call a special meeting, which can result in abrupt changes in board composition, interfere with the board’s ability to maximize stockholder value, or result in significant expense and disruption to ongoing corporate focus. A requirement that only the board or specified officers or directors are authorized to call special meetings of stockholders could, however, have the effect of delaying until the next annual meeting actions that are favored by the holders of a majority of the company’s stock.

Advance Notice Requirements

Should stockholders be required to notify the company in advance of director nominations or other matters that the stockholders would like to act upon at a stockholders’ meeting?

Advance notice requirements provide that stockholders at a meeting may only consider and act upon director nominations or other proposals that have been specified in the notice of meeting and brought before the meeting by or at the direction of the board, or by a stockholder who has delivered timely written notice to the company. Advance notice requirements afford the board ample time to consider the desirability of stockholder proposals and ensure that they are consistent with the company’s objectives and, in the case of director nominations, provide important information about the experience and suitability of board candidates. These provisions could also have the effect of delaying until the next stockholders’ meeting actions that are favored by the holders of a majority of the company’s stock.

State Anti-Takeover Laws

Should the company opt out of any state anti-takeover laws to which it is subject, such as Section 203 of the Delaware corporation statute?

Section 203 prevents a public company incorporated in Delaware (where more than 90% of all IPO companies are incorporated) from engaging in a “business combination” with any “interested stockholder” for three years following the time that the person became an interested stockholder, unless, among other exceptions, the interested stockholder attained such status with the approval of the board. A business combination includes, among other things, a merger or consolidation involving the interested stockholder and the sale of more than 10% of the company’s assets. In general, an interested stockholder is any stockholder that, together with its affiliates, beneficially owns 15% or more of the company’s stock. A public company incorporated in Delaware is automatically subject to Section 203, unless it opts out in its original corporate charter or pursuant to a subsequent charter or bylaw amendment approved by stockholders. Remaining subject to Section 203 helps eliminate the ability of an insurgent to accumulate and/or exercise control without paying a reasonable control premium, but could prevent stockholders from accepting an attractive acquisition offer that is opposed by an entrenched board.

Blank Check Preferred Stock

Should the board be authorized to designate the terms of series of preferred stock without obtaining stockholder approval?

When blank check preferred stock is authorized, the board has the right to issue shares of preferred stock in one or more series without stockholder approval under state corporate law (but subject to stock exchange rules), and has the discretion to determine the rights and preferences, including voting rights, dividend rights, conversion rights, redemption privileges and liquidation preferences, of each such series of preferred stock. The availability of blank check preferred stock can eliminate delays associated with a stockholder vote on specific issuances, thereby facilitating financings and strategic alliances. The board’s ability, without further stockholder action, to issue preferred stock or rights to purchase preferred stock can also be used as an anti-takeover device.

Multi-Class Capital Structures

Should the company sell to the public a class of common stock whose voting rights are different from those of the class of common stock owned by the company’s founders or management?

While most companies go public with a single class of common stock that provides the same voting and economic rights to every stockholder (a “one share, one vote” model), some companies go public with a multi-class capital structure under which specified pre-IPO stockholders (typically founders) hold shares of common stock that are entitled to multiple votes per share, while the public is issued a separate class of common stock that is entitled to only one vote per share. Use of a multi-class capital structure facilitates the ability of the holders of the high-vote stock to retain voting control over the company and to pursue strategies to maximize long-term stockholder value. Critics believe that a multi-class capital structure entrenches the holders of the high-vote stock, insulating them from takeover attempts and the will of public stockholders, and that the mismatch between voting power and economic interest may also increase the possibility that the holders of the high-vote stock will pursue a riskier business strategy.

Exclusive Forum Provisions

Should the company stipulate in its corporate charter or bylaws that the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware is the exclusive forum in which it and its directors may be sued by stockholders?

Following a 2010 decision by the Delaware Court of Chancery (and now expressly authorized by the Delaware corporation statute), numerous Delaware corporations have included provisions in their corporate charter or bylaws to the effect that the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware is the exclusive forum in which state-law stockholder claims may be brought against the company and its directors. Proponents of exclusive forum provisions are motivated by a desire to adjudicate stockholder claims in a single jurisdiction that has a well-developed and predictable body of corporate case law and an experienced judiciary. Opponents argue that these provisions deny aggrieved stockholders the ability to bring litigation in a court or jurisdiction of their choosing.

Stockholder Rights Plans

Should the company establish a poison pill?

A stockholder rights plan (often referred to as a “poison pill”) is a contractual right that allows all stockholders—other than those who acquire more than a specified percentage of the company’s stock—to purchase additional securities of the company at a discounted price if a stockholder accumulates shares of common stock in excess of the specified threshold, thereby significantly diluting that stockholder’s economic and voting power. Supporters believe rights plans are an important planning and strategic device because they give the board time to evaluate unsolicited offers and to consider alternatives. Rights plans can also deter a change in control without the payment of a control premium to all stockholders, as well as partial offers and “two-tier” tender offers. Opponents view rights plans, which can generally be adopted by board action at any time and without stockholder approval, as an entrenchment device and believe that rights plans improperly give the board, rather than stockholders, the power to decide whether and on what terms the company is to be sold. When combined with a classified board, rights plans make an unfriendly takeover particularly difficult.

Developments in Merger Control: It Ain’t Over ’til It’s Over

Two recent enforcement actions, one in the United States and one in Europe, serve as reminders that there are antitrust risks to be addressed after a deal is signed and even after it has closed.

Valeant: More Enforcement Against Non-Reportable Transactions

In 2015, Valeant acquired Paragon for $69 million, below the size-of-transaction threshold for notifications pursuant to the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) Act. Paragon makes polymer discs (known as “buttons”) that are used to make gas permeable contact lenses. Bausch + Lomb, a Valeant subsidiary, is also a major producer of buttons for gas permeable lenses. After acquiring Paragon, Valeant later acquired Pelican Products, the only FDA-approved supplier of packaging for a particular type of contact lens, potentially giving Bausch + Lomb sole access to Pelican’s packaging.

Even though neither transaction was reportable and both had been consummated, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) opened an investigation of both acquisitions. In November 2016, the FTC challenged Valeant’s acquisition of Paragon, alleging that Valeant and Paragon combined accounted for 65–100% of all buttons produced for three different types of gas permeable lenses. In settlement, Valeant agreed to divest the Paragon business and Pelican assets it had acquired—more than a year after the deals had closed.

While such investigations are unusual in other jurisdictions, the US antitrust agencies regularly investigate and bring enforcement actions against unreported and/or consummated transactions. If one of the agencies learns about a nonreportable transaction that it thinks may raise antitrust issues, it can and often does open an investigation. Because such investigations are not subject to the strict timelines in the HSR Act, they can be lengthy and wide-reaching. Accordingly, a party to a transaction that raises antitrust issues cannot relax just because the transaction is not reportable.

Altice: Gun-Jumping Becomes International

In 2014, cable operator Altice obtained clearance from the French Competition Authority (Autorité de la Concurrence, ADC) to purchase SFR, one of the main mobile phone operators in France. Shortly thereafter, the ADC conducted dawn raids on both companies (and another Altice subsidiary). In those raids, the ADC discovered evidence that Altice had been informed of and had involved itself in some of SFR’s corporate decisions before obtaining clearance from the ADC and consummating the transaction. For example, it appears that Altice had approved a tender offer in which SFR participated and the renegotiation of an infrastructure agreement with a competitor; Altice apparently also obtained the withdrawal of a specific discount offer and influenced SFR’s M&A strategy. Effectively, Altice gained control of SFR at least in part prior to receiving regulatory approval. To resolve these allegations, Altice paid a fine of €80 million.

In most jurisdictions, including the United States, if a transaction must be reported to the antitrust authorities, the transaction may not be consummated until the reviewing agency has granted clearance, and the parties must remain truly separate entities until closing. If one party begins to operate less than fully independently of the other party before clearance, that is known as “gun-jumping.” To date, the vast majority of gun-jumping enforcement actions have been in the United States. In foreign jurisdictions, enforcement has varied from sporadic to nonexistent; indeed, the case against Altice is the ADC’s first gun-jumping enforcement action. As this case shows, there is growing interest in gun-jumping enforcement outside of the United States, and it is reasonable to expect more such actions from non-US authorities.

Determining what is permissible and what is prohibited in the period between signing and closing of a reportable transaction is complex. In general, the parties must continue to act as independent entities until closing. They may not begin to integrate their businesses before closing, and a buyer may not influence the ordinary course day-to-day operations of the seller. The antitrust agencies have offered limited guidance regarding permissible activities prior to closing. They do, however, understand that parties need to engage in some integration planning before closing and that a buyer may have a legitimate reason for placing limits on the non-ordinary course behavior of a seller.

Takeaways

The Valeant and Altice cases are reminders that merger control is not limited to reportable transactions and the substantive antitrust/competition merits. Valeant is yet another reminder that parties to non-reportable transactions that may bring anticompetitive effects to a US market need to recognize that the lack of a filing obligation does not mean that the transaction is free from antitrust review or enforcement. Parties to mergers between competitors or mergers with potential vertical anticompetitive effects, in particular, should consider potential antitrust risk, even for small transactions. There are ways to manage risk of antitrust enforcement for non-reportable transactions (including, in some cases, voluntary notification of the transaction pre-closing), but parties to a transaction may have inconsistent incentives and so the level of risk and available methods of mitigating risk should be carefully considered pre-signing.

Altice is a reminder that managing the period between signing and closing can be complex when the transaction is reported in one or more jurisdictions. In some cases, the review period may be brief and therefore the complexity is limited. However, if the transaction raises material antitrust issues, the review period may be lengthy, and in those cases any integration planning process or consultation on non-ordinary course matters must be handled with care to avoid gun-jumping violations. While only a few—and, for the most part, only the most egregious—gun-jumping violations result in enforcement, any conduct that the agencies may view as gun-jumping can result in delay of the substantive merger investigation or harm the parties’ credibility in arguing the substantive competition merits, and will definitely increase the cost of the review process.

The Common Interest Privilege: Protecting Legal Discussions Among Deal Parties

During a deal, counsel for both sides confront myriad legal issues regarding valuation, tax treatment and regulatory compliance. Though on opposite sides of the transaction, counsel may believe coordination on these issues will improve the deal’s outcome. But such coordination also risks destroying a privilege that otherwise protects attorney-client communications from disclosure to adversaries in subsequent litigation. Fortunately, the common interest doctrine allows deal parties, in certain circumstances, to share otherwise privileged material while also protecting it from disclosure to future adversaries.

Protected Communications

Ordinarily, confidential communications between attorney and client are protected from disclosure to third parties under the attorney-client privilege. Likewise, the work product doctrine protects documents prepared as a result of reasonably anticipated or ongoing litigation. These protections can be lost, however, if a communication is disclosed to someone outside the attorney-client relationship.

The common legal interest doctrine provides an exception to this rule. It permits parties represented by separate counsel but nonetheless sharing a common legal interest to communicate regarding that legal issue without waiving the attorney-client privilege.

The doctrine presents a tantalizing option—parties can communicate shared legal concerns without fear of being exposed. Nonetheless, parties should proceed cautiously, as the strength of the doctrine’s protection will depend on: (1) the subject of the communication, (2) the persons making the communication, (3) the parties’ relationship at the time of the communication, and (4) the jurisdiction in which the privilege will be assessed.

Subject of the Communication

Courts generally agree that communications regarding a shared threat of litigation are protected. In contrast, communications regarding other shared legal concerns (absent the threat of impending litigation) are less likely to be protected.

Given that communications regarding expected litigation are more assured of protection, parties may be tempted to brand nearly all of a deal’s joint legal concerns as “anticipated litigation.” But that strategy may have unintended negative consequences, including:

- unnerving the other party by unduly emphasizing the threat of litigation;

- triggering disclosure obligations to shareholders, who may use the litigation as grounds to oppose the deal; or

- exposing both parties to disruptive and expensive document retention obligations.

Persons Making the Communication

Communications between non-lawyers are more likely to be viewed as non-legal business communications and less likely to be protected by the doctrine than communications between attorneys. Some courts have even held that the doctrine only protects communications between parties’ lawyers. Deal parties should, accordingly, communicate through their respective counsel to the extent practical or (if non-lawyers must make the communication) make clear that the communication is at the request of lawyers.

Parties’ Relationship at Time of Communication

The timing of the communication is also crucial. Before parties sign a merger agreement, communications regarding due diligence are likely not protected because the parties’ interests are still adverse. In contrast, communications regarding a regulatory inquiry will likely be protected if those communications occur after an agreement has been signed, when the parties’ interests have aligned. Thus, parties should not share sensitive information until their legal interests have aligned in some respect.

Jurisdiction in Which Privilege Will Be Assessed

Perhaps the biggest factor in determining whether the communication will be protected is the court in which it will be examined. Courts have varying interpretations of the common interest doctrine. New York’s highest court recently held that its protections do not apply unless litigation is ongoing or reasonably anticipated. Other states—for instance, Texas and Florida—have a similarly limited interpretation of the doctrine. In contrast, Delaware protects communications from disclosure regardless of whether litigation is pending or anticipated.

Conclusion

The common interest doctrine can protect privileged information shared in a transaction, but it is a tool that should be treated with caution. Communications unrelated to anticipated litigation are vulnerable to disclosure, but parties may guard against this risk by being mindful of the factors noted above.

Key Earnout Lessons for Buyers and Sellers

Acquirers sometimes pay a portion of the acquisition price through an “earnout,” in which the seller (or its stockholders) are eligible to receive additional payments based on the post-closing performance of the acquired business. An earnout can be a useful device to bridge a valuation gap between buyer and seller.

In September 2016, the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, applying New York law, issued an opinion in UMB Bank, N.A. v. Sanofi that builds upon a growing line of cases addressing a buyer’s obligations when operating a business subject to an earnout (or a contingent value right, the public company equivalent). The case provides a number of key lessons for buyers and sellers.

Background

In 2011, Sanofi acquired Genzyme, a biotechnology company, for $74.00 per share in cash plus a contingent value right of up to $14.00 per share payable upon achievement of specified milestones, including FDA approval of Lemtrada, a clinical-stage product candidate for treatment of multiple sclerosis, and achievement of commercial milestones for the drug after approval. The contingent value rights agreement (CVR agreement) entered into by Sanofi in connection with the merger required Sanofi to use “diligent efforts” to achieve the milestones. The CVR agreement defined “diligent efforts” as “using such efforts and employing such resources normally used by Persons in the pharmaceutical business.”

Following the completion of the acquisition, Sanofi did not obtain FDA approval of Lemtrada by the applicable milestone deadline, or meet the first sales milestone. The trustee on behalf of the rights holders then brought a claim for breach of contract, alleging that Sanofi breached the express terms of the CVR agreement by failing to use “diligent efforts” and also breached the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. In support of its claims, the trustee alleged, among other things, that:

- Although the FDA had expressed concerns about the methodology used in Lemtrada’s Phase III trials, Sanofi nevertheless proceeded with the same methodology.

- Sanofi was slow to respond to FDA correspondence prior to the passing of the milestone date, after which date its rate of correspondence increased. This allegedly caused the FDA to approve the drug only as a third-line treatment for the relevant indication.

- Sanofi failed to address FDA concerns or develop an appropriate sales and marketing apparatus in a timely manner.

- Sanofi expended greater efforts to commercialize a competing drug it was developing.

The Court’s Decision

The court, ruling on Sanofi’s motion to dismiss, allowed the claim for breach of contract to proceed. It held that the plaintiffs’ alleged facts were sufficient to find that Sanofi failed to use “efforts or resources normally used in the pharmaceutical business to commercialize or promote the drug” to obtain FDA approval and successfully market the drug. In particular, the court noted that the following arguably fell short of “efforts or resources normally used” by pharmaceutical companies:

- Sanofi’s inadequate response to FDA concerns;

- Sanofi’s delay in rolling out marketing materials or assembling a Lemtrada sales team; and

- Sanofi’s lack of urgency to monetize Lemtrada in light of an expiring patent. The court compared all of these deficiencies unfavorably to Sanofi’s directly analogous efforts to promote its other competing drug.

However, the court dismissed the claim for breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing because it was based on the same facts as the breach of contract claim, noting that, “under New York law … a separate cause of action for breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing … cannot lie when a breach of contract claim based on the same facts is already pleaded.” The implied covenant “does not create obligations that go beyond those intended and stated in … the contract.”

Lessons

Sanofi builds on a line of cases in Delaware and New York offering lessons for parties negotiating post-closing earnout obligations in an acquisition agreement:

- Phrases such as “diligent efforts” and “commercially reasonable efforts,” which are frequently used in earnout provisions, are often undefined or poorly defined and create a significant risk of post-closing disputes. Absent contractual provisions to the contrary, these phrases subject the post-closing behavior of the buyer to an objective test of the sufficiency of its efforts to achieve the earnout, and courts will measure a buyer’s conduct against industry standards or the conduct of peers (or, in Sanofi’s case, its efforts to commercialize a competing drug candidate).

- Buyers should try to qualify any restrictions on their post-closing business operations by providing that their actions or inactions must not be “taken with the intent of avoiding or reducing the payment of any earnout payment” or similar language. Courts have placed significant emphasis on this language in finding that post-closing actions or inactions with a justifiable business justification do not violate the earnout requirements.

- Courts are reluctant to infer obligations on the part of the buyer based on the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing if the acquisition agreement describes in reasonable detail what the buyer is required to do (and perhaps more importantly, what the buyer is not required to do).

- Conversely, courts are more willing to allow breach of contract claims to proceed if the sellers can point to specific obligations in an acquisition agreement that the buyer has allegedly failed to meet. Sellers should consider carefully what obligations are important to the achievement of the earnout and should negotiate for their inclusion in the contract, and buyers should consider what obligations they are willing to accept. It can be in both parties’ interest to describe post-closing requirements in reasonable detail.

- While buyers generally do not have a common law obligation to maximize an earnout, they should not take actions intended to harm the acquired company’s ability to achieve the earnout without a bona fide business reason.

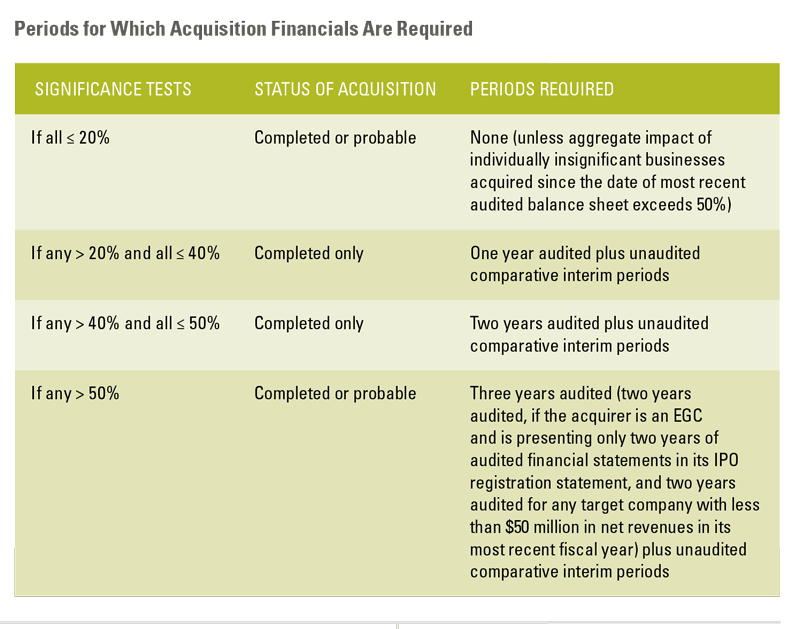

Acquisition Financial Statement Requirements in an IPO

The basic financial statement requirements for a company going public are well known. No sensible company would embark on the IPO process if it did not believe that it could satisfy these obligations. Less familiar to many IPO candidates—and sometimes the cause of unpleasant surprises for unsuspecting companies, even late in the process—is the possible need for additional financial statements and pro forma financial information in circumstances involving significant acquisitions, dispositions and equity investments. These additional requirements, which are described below, are imposed by SEC rules and are not required by GAAP.

Significant Acquisitions

General Requirements

Significance Tests. Subject to the limited exceptions described below and based on the application of three significance tests, Rule 3-05 of Regulation S-X requires separate financial statements for a significant “business” that is acquired by a company during the periods presented in its Form S-1 registration statement. Separate financial statements for a business whose acquisition is “probable” but not yet completed are also required if the proposed acquisition meets—at the 50% level—any of the three significance tests for acquisition financials.

Definition of “Business.” Rule 11-01(d) of Regulation S-X provides that the term “business” should be evaluated in light of the facts and circumstances involved and whether there is sufficient continuity of the acquired entity’s operations prior to and after the acquisition to make disclosure of prior financial information material to an understanding of future operations. A presumption exists that a separate entity, subsidiary or division is a business, but a lesser component of an entity may also constitute a business.

Among the facts and circumstances that should be considered in evaluating whether a lesser component of an entity constitutes a business are whether the nature of the revenue-producing activity of the component will remain generally the same as before the acquisition, and whether any of the following attributes remain with the component after the acquisition: physical facilities, employee base, market distribution system, sales force, customer base, operating rights, production techniques or trade names. In practice, the term “business” is interpreted broadly, and most acquisitions meeting the applicable significance tests trigger the requirement for separate financial statements.

Definition of “Probable.” Regulation S-X does not define the word “probable.” In general, a proposed acquisition will not be considered probable if a definitive agreement has not been signed, and a proposed acquisition will be considered probable if a definitive agreement has been signed and closing is subject only to normal closing conditions. Even if a potential transaction is not probable and thus does not require separate financial statements under Rule 3-05, some disclosure about the transaction may be required in the Form S-1 to satisfy general antifraud requirements, or if a portion of the IPO proceeds will be used to finance the acquisition.

Treatment of Related Businesses. Regulation S-X treats completed or probable acquisitions of “related” businesses as a single transaction for the purposes of determining whether financial statements are required to be included and, if so, which financial statements are needed. For this purpose, businesses are deemed to be related if they are under common control or management; the acquisition of one business is conditioned on the acquisition of the other business; or each acquisition is conditioned on a single common event.

Required Periods. Depending on the significance of the business whose acquisition is completed or probable, the company may be required to include separate financial statements of the business for up to three fiscal years plus any subsequent interim period (and the comparative prior interim period), as well as pro forma financial information presenting the combination of the company and the acquired business for the most recent fiscal year and any subsequent interim period (but not the comparative prior interim period). The periods for which separate financial statements are required are determined by reference to the significance tests for acquisition financials.

In some circumstances, Rule 3-06 of Regulation S-X permits audited financial statements of an acquired business (but not of the registrant) covering a period of nine to twelve months to satisfy the requirement of financial statements for a period of one year. In addition, in an IPO registration statement, an acquirer may apply the period of time in which the operations of an acquired business are included in the audited income statement of the acquirer to reduce the number of periods for which pre-acquisition income statements are required, if there is no gap between the audited pre-acquisition and audited post-acquisition periods.

Standards for Separate Financial Statements. If required, the separate financial statements generally must meet the standards applicable to the company’s own financial statements, except:

- the separate financial statements need not comply with accounting standards that do not apply at all to nonpublic companies (such as those related to segment reporting and earnings-per-share calculations);

- the effects of any nonpublic company accounting standards must be removed from the separate financial statements; and

- the auditor need not be registered with the PCAOB and need not satisfy SEC and PCAOB independence rules with respect to the company, unless the business whose acquisition has been completed or become probable is deemed to be a predecessor of the company.

Pro Forma Financial Information. In addition to the separate financial statements described above, Rule 11-01 of Regulation S-X requires the inclusion of pro forma financial information—presenting the combination of the company and the acquired business after giving effect to purchase adjustments—that meets the requirements of Rule 11-02 if:

- during the company’s most recent fiscal year or subsequent interim period for which a balance sheet is required, a significant business combination (at the 20% level of significance) has been completed;

- after the date of the company’s most recent balance sheet, a significant business combination (at the 20% level of significance) has been completed or become probable (at the 50% level of significance);

- the company previously was a part of another entity and such presentation is necessary to reflect the operations and financial position of the company as an autonomous entity; or

- consummation of other events or transactions has occurred or is probable for which disclosure of pro forma financial information would be material to investors.

The required pro forma information generally consists of a condensed balance sheet as of the end of the most recent period for which a consolidated balance sheet of the company is required in the Form S-1, and condensed statements of income for the company’s most recent fiscal year and any subsequent interim period. The company may elect to include a pro forma condensed statement of income for the corresponding interim period of the preceding fiscal year, but ordinarily does not unless doing so would be helpful to explain some aspect of the combined company’s business, such as seasonality.

When more than one acquisition has been completed or become probable during a fiscal year, the cumulative effect of the acquisitions must be assessed to determine whether pro forma financial information is required. If the cumulative effect of the acquisitions exceeds 50% for any of the significance tests described above, pro forma financial information must be presented for the required periods based on the cumulative magnitude of the significance test.

Potential Complications. Satisfaction of the acquisition financial statement requirements of Regulation S-X can be challenging when the target business is a division, business unit or collection of assets that does not have separate financial statements and was never separately audited. When an acquisition is probable but not completed, additional complications can arise if separate financial statements do not exist and the company does not have a contractual right to conduct an audit. The requirements of Regulation S-X can be especially problematic if an acquired business is in a foreign jurisdiction in which accounting practices do not enable the preparation of financial statements that can be audited for SEC purposes.

Exceptions

Several exceptions to the acquisition financial statement requirements described above provide some relief.

- EGCs: An emerging growth company (EGC) may omit from its Form S-1 financial statements of an acquired business otherwise required by Regulation S-X, provided that (1) the omitted financial information relates to a historical period that the EGC reasonably believes will not be required at the time of the contemplated offering and (2) the EGC amends its Form S-1 to include all financial information required by Regulation S-X at the date of such amendment before distributing a preliminary prospectus to investors.

- Recent Acquisitions: Separate financial statements and pro forma financial information are not required to be included in the Form S-1 for acquisitions completed within 74 days before the date of the final prospectus if none of the significance tests are met at the 50% level and the omitted financial statements and pro forma financial information are filed on a Form 8-K no later than 75 days after completion of the acquisition. The purpose of this exception is to allow IPO companies, in most circumstances, to provide information about significant acquisitions on the same basis as existing public companies are required to do under the Exchange Act.

- Roll-Up Companies: Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 80 provides that, in the case of IPOs by businesses that have been built by the aggregation of discrete businesses that remain substantially intact after acquisition, the company may assess the significance of an acquisition based on the company’s consolidated financial statements at the time of the initial Form S-1 filing (or confidential submission, if applicable) rather than at the time of the acquisition.

Significance Tests for Acquisition Financials

The significance tests for acquisition financials are based on the definition of a “significant subsidiary” under Rule 1-02(w) of Regulation S-X, as follows:

- Investment Test: The investments in and advances to the target by the company and its consolidated subsidiaries exceed 20% of the total assets of the company and its consolidated subsidiaries as of the end of the most recently completed fiscal year.

- Asset Test: The proportionate share of the company and its consolidated subsidiaries of the total assets (after intercompany eliminations) of the target exceeds 20% of the total assets of the company and its consolidated subsidiaries as of the end of the most recently completed fiscal year.

- Income Test: The equity of the company and its consolidated subsidiaries in the target’s income from continuing operations before income taxes, extraordinary items and cumulative effect of a change in accounting principle exceeds 20% of such income of the company and its consolidated subsidiaries for the most recently completed fiscal year.

Significant Dispositions

Rule 11-01 of Regulation S-X requires a company to present pro forma financial information if its disposition of a significant portion of a business—whether by sale, abandonment or distribution to stockholders by means of a spin-off, split-up or split-off—has occurred or is probable and such disposition is not fully reflected in the company’s financial statements included in the Form S-1. For this purpose, the disposition of “a significant portion of a business” means the disposition of a significant subsidiary, as defined above, except that the percentage changes from 20% to 10% for each test of significance.

Rule 11-02 provides that a company must prepare pro forma financial information for a disposition by beginning with the historical financial statements of the existing entity and showing the deletion of the business being divested, along with the pro forma adjustments necessary to arrive at the remainder of the existing entity. For example, pro forma adjustments would include adjustments of interest expense arising from a revised debt structure, and removal of expenses that have been incurred on behalf of the business being divested.

The periods for which pro forma financial information for significant dispositions must be presented are generally the same as the required periods for significant acquisitions. In the case of discontinued operations that are not yet required to be reflected in historical statements, however, three years of pro forma income statements and any subsequent interim period are required. In the case of an EGC that is presenting only two years of audited financial statements in its IPO registration statement, the foregoing periods are shortened to two years.

Separate financial statements for a business whose disposition has occurred or is probable are not required to be presented in the Form S-1. The pro forma financial information described above will suffice.

Significant Equity Investments

The company’s equity investments also may trigger the need for separate financial statements. If either the investment test or the income test is met at the 20% level for a 50% or less owned entity and the company accounts for the investment by the equity method, Rule 3-09 of Regulation S-X requires separate financial statements of such entity. This means, for example, that the company may be required to provide separate financial statements for entities in which it holds equity investments, or for joint ventures.

If the applicable significance tests are met, the requirement for separate financial statements can even extend to equity investments or joint ventures that existed at any point during the previous three years but have since been divested. While all three years are required to be presented once significance is reached, only the years for which significance is greater than 20% are required to be audited. In the case of an EGC that is presenting only two years of audited financial statements in its IPO registration statement, the foregoing periods are shortened to two years.

Relief From Financial Statement Requirements

Relief may be sought from the SEC to permit the omission of any financial statements required by Regulation S-X or the substitution of “appropriate statements of comparable character.” Rule 3-13 requires that the relief be “consistent with the protection of investors.” The SEC will not waive compliance with GAAP accounting requirements.

The process of seeking relief can be time-consuming and its outcome uncertain. The company will stand the best chance of success if it can demonstrate that the required financial statements cannot be obtained and that any substituted financial information will provide all material financial information needed by investors. The company can bolster its case by demonstrating that satisfaction of the requirement would involve “unreasonable effort or expense”—the general standard contained in Rule 409 under the Securities Act for relief from SEC disclosure requirements.

In theory, these standards for relief sound reasonably attainable; in practice, a company is rarely excused from providing historical or pro forma financial information in connection with an acquisition or disposition transaction, although a request to provide substituted financial information may be granted in appropriate circumstances.

Conclusion

If a private company planning to go public has engaged in M&A activity (whether as a buyer or seller), it should review with its auditor whether any additional financial statements will be required as part of its SEC registration process; if so, determine if they are available; and if not, develop a plan to obtain them, which may require auditing or re-auditing the acquired company’s financial statements. In some cases, the company may need to consider shelving its M&A plans until the IPO is completed, to avoid these issues.

Comparison of Deal Terms in Public and Private Acquisitions

Public and private company M&A transactions share many characteristics, but also involve different rules and conventions. Described below are some of the ways in which acquisitions of public and private targets differ.

General Considerations

The M&A process for public and private company acquisitions differs in several respects:

- Structure: An acquisition of a private company may be structured as an asset purchase, a stock purchase or a merger. A public company acquisition is generally structured as a merger, often in combination with a tender offer for all-cash acquisitions.

- Letter of Intent: If a public company is the target in an acquisition, there is usually no letter of intent. The parties typically go straight to a definitive agreement, due in part to concerns over creating a premature disclosure obligation. Sometimes an unsigned term sheet is also prepared.

- Timetable: The timetable before signing the definitive agreement is often more compressed in an acquisition of a public company. More time may be required between signing and closing, however, because of the requirement to prepare and file disclosure documents with the SEC and comply with applicable notice and timing requirements, and the need in many public company acquisitions for antitrust clearances that may not be required in smaller, private company acquisitions.

- Confidentiality: The potential damage from a leak is much greater in an M&A transaction involving a public company, and accordingly rigorous confidentiality precautions are taken.

- Director Liability: The board of a public target will almost certainly obtain a fairness opinion from an investment banking firm and is much more likely to be challenged by litigation alleging a breach of fiduciary duties.

Due Diligence

When a public company is acquired, the due diligence process differs from the process followed in a private company acquisition:

- Availability of SEC Filings: Due diligence typically starts with the target’s SEC filings—enabling a potential acquirer to investigate in stealth mode until it wishes to engage the target in discussions.

- Speed: The due diligence process is often quicker in an acquisition of a public company because of the availability of SEC filings, thereby allowing the parties to focus quickly on the key transaction points.

Merger Agreement

The merger agreement for an acquisition of a public company reflects a number of differences from its private company counterpart:

- Representations: In general, the representations and warranties from a public company are less extensive than those from a private company; are tied in some respects to the accuracy of the public company’s SEC filings; may have higher materiality thresholds; and, importantly, do not survive the closing.

- Exclusivity: The exclusivity provisions are subject to a “fiduciary exception” permitting the target to negotiate with a third party making an offer that may be deemed superior and to change the target board’s recommendation to stockholders.

- Closing Conditions: The closing conditions in the merger agreement, including the “no material adverse change” condition, are generally tightly drafted, and give the acquirer little room to refuse to complete the transaction if all required regulatory and stockholder approvals are obtained.

- Post-Closing Obligations: Post-closing escrow or indemnification arrangements are very rare.

- Earnouts: Earnouts are unusual, although a form of earnout arrangement called a “contingent value right” is not uncommon in the life sciences sector.

- Deal Certainty and Protection: The negotiation battlegrounds are the provisions addressing deal certainty (principally the closing conditions) and deal protection (exclusivity, voting agreement, termination and breakup fees).

SEC Involvement

The SEC plays a role in acquisitions involving a public company:

- Form S-4: In a public acquisition, if the acquirer is issuing stock to the target’s stockholders, the acquirer must register the issuance on a Form S-4 registration statement that is filed with (and possibly reviewed by) the SEC.

- Stockholder Approval: Absent a tender offer, the target’s stockholders, and sometimes the acquirer’s stockholders, must approve the transaction. Stockholder approval is sought pursuant to a proxy statement that is filed with (and often reviewed by) the SEC. Public targets seeking stockholder approval generally must provide for a separate, non-binding stockholder vote with respect to all compensation each named executive officer will receive in the transaction.

- Tender Offer Filings: In a tender offer for a public target, the acquirer must file a Schedule TO and the target must file a Schedule 14D-9. The SEC staff reviews and often comments on these filings.

- Public Communications: Elaborate SEC regulations govern public communications by the parties in the period between the first public announcement of the transaction and the closing of the transaction.

- Multiple SEC Filings: Many Form 8-Ks and other SEC filings are often required by public companies that are party to M&A transactions.

Set forth below is a comparison of selected deal terms in public target and private target acquisitions, based on the most recent studies available from SRS|Acquiom (a provider of post-closing transaction management services) and the Mergers & Acquisitions Committee of the American Bar Association’s Business Law Section. The SRS|Acquiom study covers private target acquisitions in which it served as shareholder representative and that closed in 2015. The ABA private target study covers acquisitions that were completed in 2014, and the ABA public target study covers acquisitions that were announced in 2015 (excluding acquisitions by private equity buyers).

Comparison of Selected Deal Terms

The accompanying chart compares the following deal terms in acquisitions of public and private targets:

- “10b-5” Representation: A representation to the effect that no representation or warranty by the target contained in the acquisition agreement, and no statement contained in any document, certificate or instrument delivered by the target pursuant to the acquisition agreement, contains any untrue statement of a material fact or fails to state any material fact necessary, in light of the circumstances, to make the statements in the acquisition agreement not misleading.

- Standard for Accuracy of Target Reps at Closing: The standard against which the accuracy of the target’s representations and warranties set forth in the acquisition agreement is measured for purposes of the acquirer’s closing conditions (sometimes with specific exceptions):

- A “MAC/MAE” standard provides that each of the representations and warranties of the target must be true and correct in all respects as of the closing, except where the failure of such representations and warranties to be true and correct will not have or result in a material adverse change/effect on the target.

- An “in all material respects” standard provides that the representations and warranties of the target must be true and correct in all material respects as of the closing.

- An “in all respects” standard provides that each of the representations and warranties of the target must be true and correct in all respects as of the closing.

- Inclusion of “Prospects” in MAC/MAE Definition: Whether the “material adverse change/effect” definition in the acquisition agreement includes “prospects” along with other target metrics, such as the business, assets, properties, financial condition and results of operations of the target.

- Fiduciary Exception to “No-Talk” Covenant: Whether the “no-talk” covenant prohibiting the target from seeking an alternative acquirer includes an exception permitting the target to consider an unsolicited superior proposal if required to do so by its fiduciary duties.

- Opinion of Target’s Counsel as Closing Condition: Whether the acquisition agreement contains a closing condition requiring the target to obtain an opinion of counsel, typically addressing the target’s due organization, corporate authority and capitalization; the authorization and enforceability of the acquisition agreement; and whether the transaction violates the target’s corporate charter, bylaws or applicable law. (Opinions regarding the tax consequences of the transaction are excluded from this data.)

- Appraisal Rights Closing Condition: Whether the acquisition agreement contains a closing condition providing that appraisal rights must not have been sought by target stockholders holding more than a specified percentage of the target’s outstanding capital stock. (Under Delaware law, appraisal rights generally are not available to stockholders of a public target when the merger consideration consists solely of publicly traded stock.)

- Acquirer MAC/MAE Closing Condition: Whether the acquisition agreement contains a closing condition excusing the acquirer from closing if an event or development has occurred that has had, or could reasonably be expected to have, a “material adverse change/effect” on the target.

Trends in Selected Deal Terms

The ABA deal term studies have been published periodically, beginning with public target acquisitions that were announced in 2004 and private target acquisitions that were completed in 2004 (not all metrics discussed below were reported for all periods). A review of past studies identifies the following trends, although in any particular transaction negotiated outcomes may vary:

In transactions involving public company targets:

- “10b-5” Representations: These representations, whose frequency had fallen steadily from a peak of 19% of acquisitions announced in 2004, were not present in any acquisitions announced in 2015.

- Accuracy of Target Reps at Closing: The MAC/MAE standard for accuracy of the target’s representations at closing remains almost universal, present in 98% of acquisitions announced in 2015 compared to 89% of acquisitions announced in 2004 (and having peaked at 100% in 2010). In practice, this trend has been offset to some extent by the use of lower standards for specific representations, such as those relating to capitalization and authority.

- Inclusion of “Prospects” in MAC/MAE Definition: The target’s “prospects” were included in the MAC/MAE definition in only 1% of acquisitions announced in 2015, representing a sharp decline in frequency from 10% of acquisitions announced in 2004.

- Fiduciary Exception to “No-Talk” Covenant: The fiduciary exception in 95% of acquisitions announced in 2015 was based on the concept of “an acquisition proposal expected to result in a superior offer,” up from 79% in 2004 but down slightly from 98% in 2012, while the standard based on the mere existence of any “acquisition proposal,” which did not appear in any acquisitions announced in 2011–2012, was present in 4% of acquisitions announced in 2015 (down from 7% in 2014). The standard based on an actual “superior offer” declined from 11% in 2004 to just 1% in 2015. In practice, these trends have been partly offset by an increase in “back-door” fiduciary exceptions, such as the “whenever fiduciary duties require” standard.

- “Go-Shop” Provisions: “Go-shop” provisions, granting the target a specified period of time to seek a better deal after signing an acquisition agreement, appeared in 3% of acquisitions announced in 2007. The incidence of these provisions grew to 11% in 2013, before decreasing to 6% in 2015.

- Appraisal Rights Closing Condition: For the second consecutive year, no cash acquisitions announced in 2015 had an appraisal rights closing condition, compared to 13% of cash acquisitions announced in 2005–2006. An appraisal rights closing condition appeared in 6% of cash/stock acquisitions announced in 2015, down sharply from 13% in 2014 and 26% in 2013 but still above the low point of 4% in 2011.

In transactions involving private company targets:

- “10b-5” Representations: The prevalence of these representations has declined from 59% of acquisitions completed in 2004 to 25% of acquisitions completed in 2014.

- Accuracy of Target Reps at Closing: The MAC/MAE standard for accuracy of the target’s representations at closing has gained wider acceptance, appearing in some form in 43% of acquisitions completed in 2014 compared to 37% of acquisitions completed in 2004.

- Inclusion of “Prospects” in MAC/MAE Definition: The target’s “prospects” appeared in the MAC/MAE definition in 12% of acquisitions completed in 2014, down from 36% of acquisitions completed in 2006.

- Fiduciary Exception to “No-Talk” Covenant: Fiduciary exceptions were present in 10% of acquisitions completed in 2014, compared to 25% of acquisitions completed in 2008.

- Opinions of Target Counsel: Legal opinions (excluding tax matters) of the target’s counsel have fallen in frequency from 73% of acquisitions completed in 2004 to 11% of acquisitions completed in 2014.

- Appraisal Rights Closing Condition: An appraisal rights closing condition was included in 49% of acquisitions completed in 2014, up from 43% of acquisitions completed in 2008.

Post-Closing Claims

SRS|Acquiom has released a study analyzing post-closing escrow claim activity in 720 private target acquisitions in which it served as shareholder representative from 2010 through 2014. This study provides a glimpse into the hidden world of post-closing escrow claims in private acquisitions:

- Expense Fund: Median size of $200,000 (0.25% of transaction value). 75% of deals used less than 10% of expense fund.

- Frequency of Claims: 60% of all transactions had at least one post-closing indemnification claim (including purchase price adjustments) against the escrow. 25% had more than one claim.

- Size of Claims: On average, claims represented 24% of the escrow. 6% of all deals had claims match or exceed the escrow, and 9% of all deals had claims for half or more of the escrow. Largest claims were for fraud and breach of fiduciary duty.

- Bases for Claims: Most frequently claimed misrepresentations involved tax (18% of transactions), intellectual property (11% of transactions), undisclosed liabilities (8% of transactions) and employee-related (8% of transactions).

- Resolution of Claims: 9% of all transactions with claims had claims litigated or arbitrated. On average, contested claims were resolved in seven months.

- Purchase Price Adjustments: 77% of all transactions had mechanisms for purchase price adjustments. Of these, 65% had a post-closing adjustment (favorable to the acquirer in 48% of transactions and favorable to target stockholders in 17% of transactions).

- Earnouts: In non-life sciences transactions, 56% of milestones that came due were paid to some degree and 15% of milestones that were initially claimed to be missed were disputed and resulted in negotiated payouts for target stockholders.

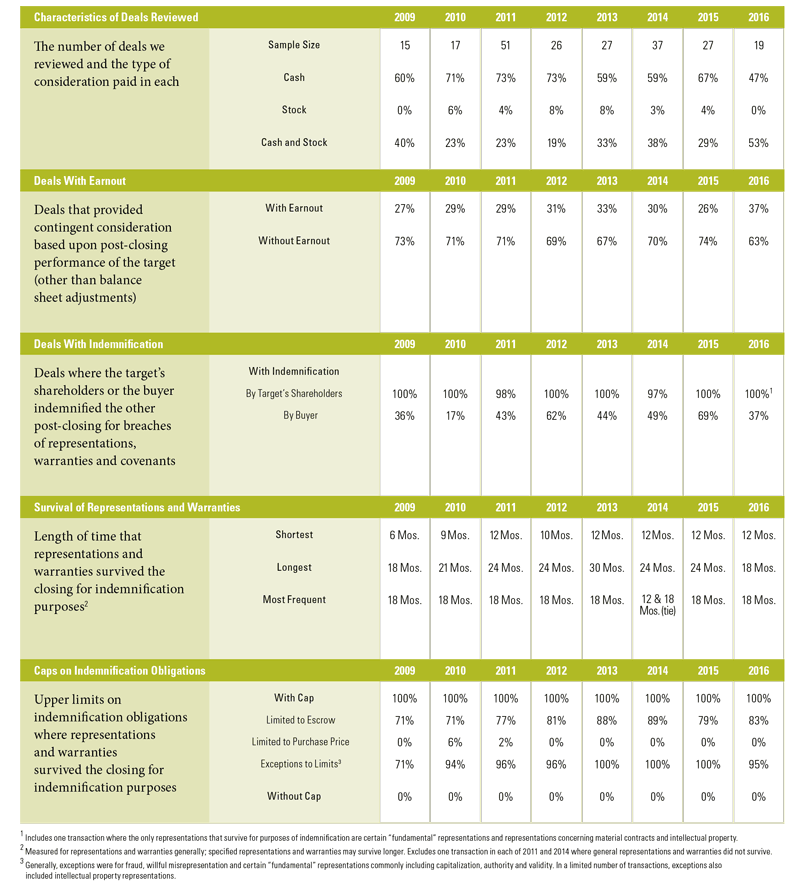

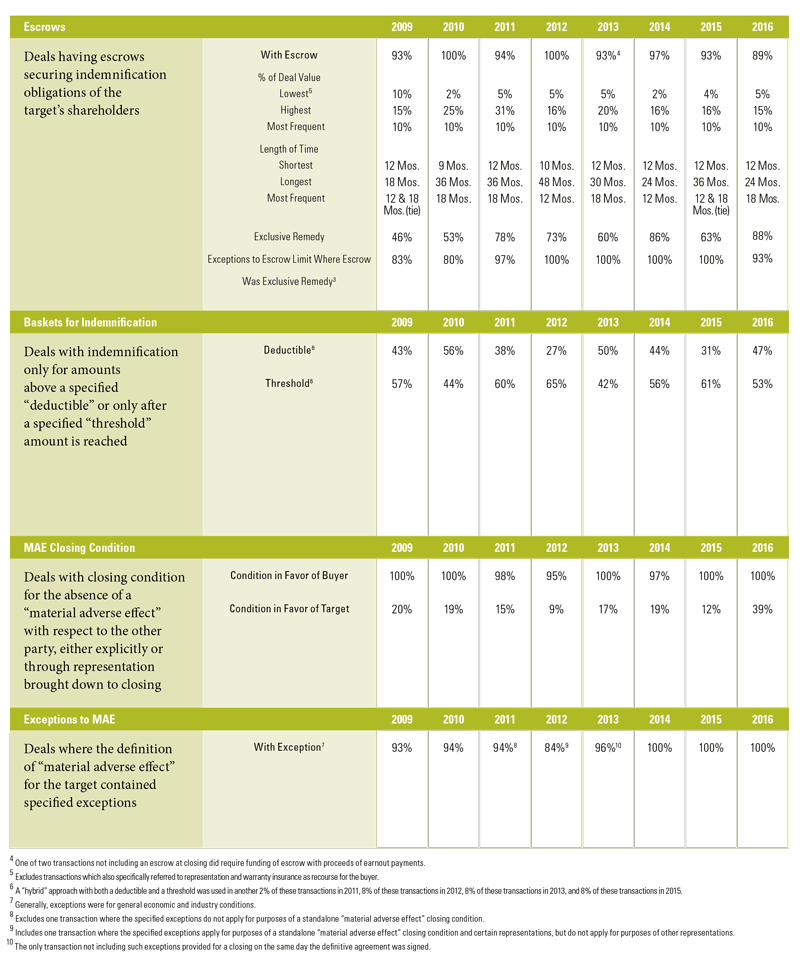

Trends in VC-Backed Company M&A Deal Terms

We reviewed all merger transactions between 2009 and 2016 involving venture-backed targets (as reported in Dow Jones VentureSource) in which the merger documentation was publicly available and the deal value was $25 million or more. Based on this review, we have compiled the following deal data:

Print

Print