Loukas Karabarbounis is Professor of Economics at the University of Minnesota; Brent Neiman is Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. This post is based on a recent article, forthcoming in the Journal of Monetary Economics, by Professor Karabarbounis, Professor Neiman, and Peter Chao-Wen Chen, University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

The sectoral composition of global saving changed dramatically during the last three decades. Whereas in the early 1980s most of global investment was funded by household saving, nowadays nearly two-thirds of global investment is funded by corporate saving. In The Global Rise of Corporate Saving we characterize patterns of sectoral saving and investment for a large set of countries over the past three decades. We measure the flow of corporate saving from the national income and product accounts as undistributed corporate profits.

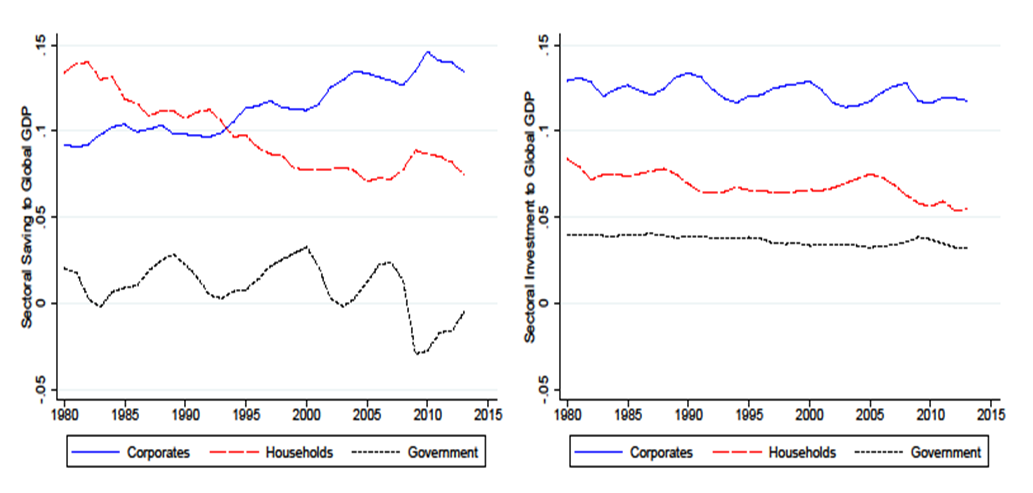

Figure 1: Global Sectoral Saving and Investment Trends

The left panel of Figure 1 shows corporate, household, and government saving as a fraction of global GDP. Global corporate saving has risen from roughly 9 percent of global GDP in 1980 to almost 14 percent in 2015. Household saving has also exhibited a dramatic change but of the opposite sign, leaving the global total saving rate relatively constant. [1] The right panel shows that, unlike saving, the sectoral composition of investment has been relatively stable over time. The corporate sector transitioned from a net borrower to a net lender of funds to the rest of the global economy. Contrary to common belief, this rise of corporate saving significantly predates the global financial crisis.

Using national accounts data, we find that corporate saving increased in the majority of countries, including all ten of the largest economies in the world. Using firm-level data, we find that corporate saving and corporate net lending increased in the majority of industries. We do not find evidence that trends in firm saving relate significantly to firm age or size. Increases in corporate saving within industry and types of firms, rather than shifts of economic activity between groups, account for the majority of the global rise in corporate saving. Taken together, our results suggest that the rise of corporate saving is a pervasive phenomenon and it is unlikely to reflect structural changes (e.g. the decline in manufacturing), idiosyncratic changes of particular firms or industries, or changes in corporate financial practices in particular firms or countries.

Corporate saving is undistributed (accounting) profits, or equivalently the part of corporate value added (or corporate GDP) that is not paid to taxes, to labor, to debt holders, or to equity holders. Using national accounts data, we document that taxes, interest payments, and dividends have remained essentially constant over time as a share of global GDP. Using firm-level data, we show that firms with larger increases in their (accounting) profits experienced larger increases in their saving rates but were not significantly different in their tax, dividend, or interest payments. The rise of corporate saving, therefore, emerged as the decline in the labor share pushed up corporate profits and dividend growth did not keep pace.

An increase in the flow of corporate saving relative to expenditures on physical investment implies an improvement in the net lending position of the corporate sector. How were these additional resources used? Among other possibilities, firms can buy back their shares, pay down their debt, and accumulate cash or other financial assets. Using firm-level data, we document that the balance sheet adjustment involved all three of these categories. However, we find interesting differences over time. Increases in firm net lending were more likely to be stockpiled as cash starting in the early 2000s and were less likely to be used to buy back shares after the financial crisis.

Our analysis highlights that the proximate cause of the rise of corporate saving was the combination of a declining global labor share and the stability of the dividend share of output. What might have been the deeper forces underlying these trends? We develop a model in which capital market imperfections such as dividend taxes, costs to raising equity, and debt constraints affect the flow of funds between corporations and households. We parameterize the model to represent the global economy in the early 1980s and feed into it changes in components of the cost of capital that we measure from the data, such as the declines in the real interest rate, corporate income taxes, and the price of investment goods, alongside an increase in firm markups and the slowdown of growth observed after the Great Recession. Our model generates a rise of corporate saving and a decline in household saving similar in magnitude to those observed in the data. The decline in the cost of capital and the increase in firm markups led to a decline in labor’s share and an increase in accounting profits. Given the stickiness of dividend payments, these additional resources were retained within the corporate sector rather than paid back to shareholders.

The complete article is available for download here.

Endnotes

1Corporate saving together with government and household saving equal total national saving.(go back)

Print

Print