Paula Loop is Leader of the Governance Insights Center at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Ms. Loop.

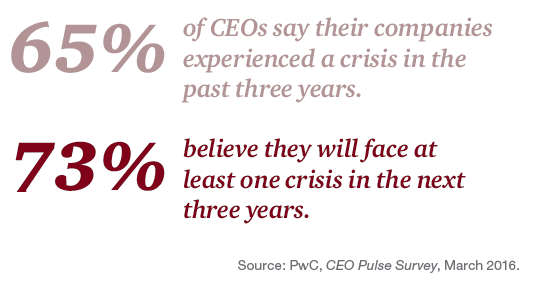

Most companies experience at least one crisis every four or five years. Regularly discussing the crisis plan with management and the results from testing it lets the board understand where there might be gaps in readiness. And it’s always better to know about those gaps before a crisis hits. Directors themselves might even need to take a more active role if a crisis spins out of control. Is your board prepared?

We’ve all seen cases of a company crisis that ballooned out of control and wondered how the company made so many obvious mistakes. Of course, it’s easy to be an armchair quarterback, but ensuring management is ready to handle a crisis is an important part of the board’s risk oversight. Trying to figure this out while a company is in the midst of a crisis is simply too late.

When something starts to go wrong, it can even be tough to figure out if it’s a true crisis. And it may be impossible to predict the full effects—on operations, results or reputation. Even a crisis that’s small at the outset can mushroom if it’s mishandled.

All companies will face a crisis at some point. So it’s important for directors to understand whether management has a sound crisis plan in place and to be alert for challenges that commonly arise in crises—before, during and after a crisis occurs.

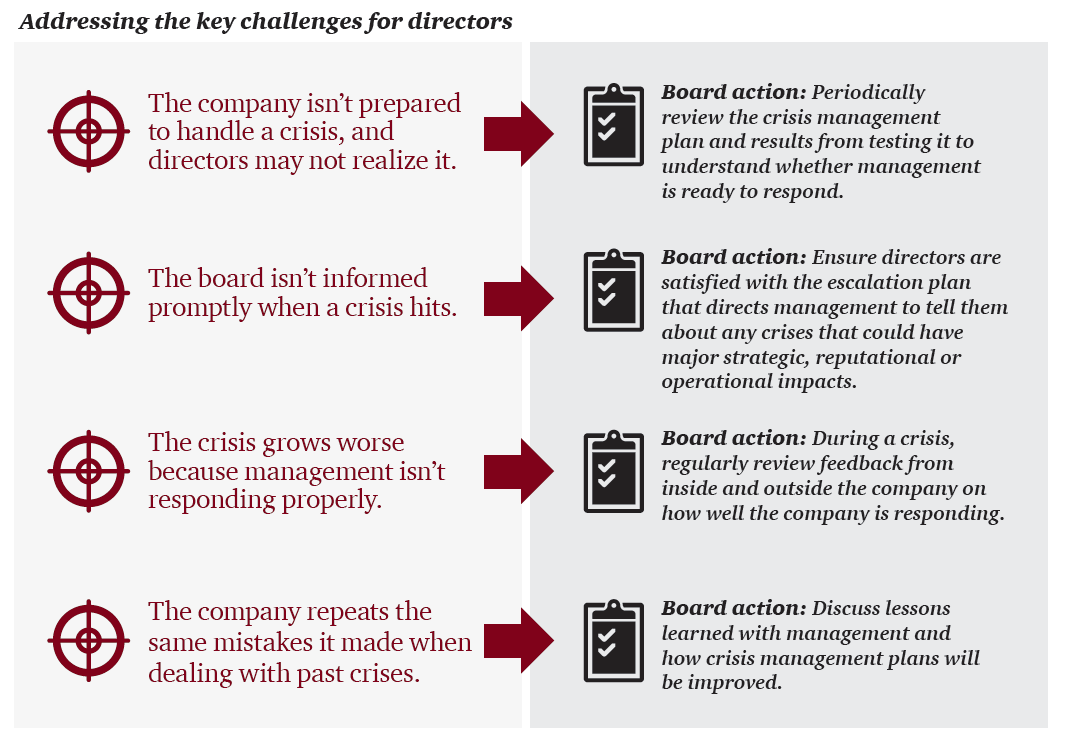

Challenge: The company isn’t prepared to handle a crisis, and directors may not realize it.

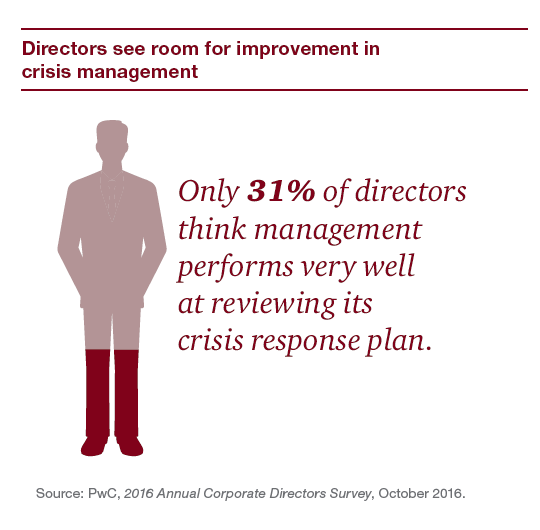

Some boards still aren’t asking about crisis management plans. Perhaps they’re taking the “fingers crossed” approach of hoping management will be able to handle any crisis that arises. PwC’s 2015 Annual Corporate Directors Survey found that 23% had not discussed the subject with management at all and 38% hadn’t discussed management’s testing of the plan. So it’s not surprising that the same survey found that more than a quarter of directors say their board’s performance in overseeing crisis management preparedness needs improvement.

And while directors think their boards need to improve, they also clearly think management can do better.

Board action: Periodically review the crisis management plan and results from testing it to understand whether management is ready to respond.

First, ensure the topic of crisis management is on the board’s agenda—ideally every year. Understand what a plan should cover to be effective and have management discuss any gaps. Directors will particularly want to focus on who will be involved in responding to a crisis, and whether those people understand their roles and responsibilities. It’s also valuable to discuss with management how other companies handled their crises and whether management has considered lessons from what worked and what didn’t to improve its own plans.

Elements of effective crisis management plans

- Engages a cross functional team for planning and execution

- Identifies crisis management leader(s)

- Delineates roles and responsibilities, including the CEO’s and board’s roles

- Defines the crisis escalation process

- Outlines expected crisis management activities

- Defines disaster recovery priorities

- Identifies outside advisors to retain as needed

- Provides guidance on crisis communication strategies, including use of social media

- Requires regular testing of the plan

Next, understand how management tests its plans. Using a simulated crisis can test how a company would respond in real time, and whether roles and activities are working together as envisioned in the plan. Also ask whether the company’s crisis simulations or tabletop exercises require participants to agree on when and how to inform the board and other stakeholders. Often these exercises identify areas of confusion and uncertainty, and expose gaps in the crisis plan. So, ask about lessons learned—and which areas of the plans management needs to update.

Even the best management team with a solid well-tested plan may not have all the tools or knowledge to handle every crisis. When executives think about the likely types of crises the company might face, they should also identify who can help, including legal, crisis management and communications experts. Knowing who to call ahead of any crisis can save time—and minimize impacts.

Finally, make sure senior executives—including the CEO—are involved in crisis plan testing. They set the tone and have critical roles. If they think a crisis exercise doesn’t warrant their attention, others won’t either. These are not “one and done” exercises. Periodic testing helps to build and strengthen the company’s capability.

Challenge: The board isn’t informed promptly when a crisis hits.

The board hires a CEO it trusts to run the company, including to manage the many challenges and problems a company inevitably runs into. Few everyday incidents require immediate board-level attention.

But from time to time, a major event—from a natural disaster like an earthquake to a man-made one like a data breach—can turn into a crisis for a company. These types of isolated incidents are relatively easy to identify as crises. What’s more difficult are the issues that start small—incidents that local business unit management think they can handle and put behind them. It can be difficult to figure out at which point the issue needs to be escalated—and the board informed.

Board action: Ensure directors are satisfied with the escalation plan that directs management to tell them about any crises that could have major strategic, reputational or operational impacts.

First, understand how management defines a “crisis.” It’s not as easy as it sounds. Whether there’s a formal definition or not, the board should discuss when and how it wants to be notified about a looming or ongoing crisis. Much will depend on the nature and scope of the crisis—there is no single answer to when management ought to inform the board. So discuss possible scenarios with management that would require board involvement. And make sure the company’s crisis management plan includes a section on board engagement that clearly outlines the escalation expectations and process.

Examples of triggers that would require management to escalate an issue to the board

- Any time people have been hurt

- A plant has been severely damaged

- The crisis will have a significant financial impact

- Critical systems are offline for a specified period of time

- An event occurs that is getting significant negative social media attention

Challenge: The crisis grows worse because management isn’t responding properly

When a company is in the middle of a crisis, there are many ways the response may fail.

1. Uncertain crisis scope. Perhaps it’s the complex nature of the issue that makes it difficult to understand the scope at the outset. For example, with cyberattacks, it’s difficult to know the extent of information compromised or when some of that stolen information may be published or used. Or maybe it’s an issue with the company’s products—and management is uncertain how widespread the problems are. Or it could be that the crisis occurred in a location that’s almost impossible to reach—whether it’s deep underwater or in a part of the world where transportation routes or communications channels have been cut.

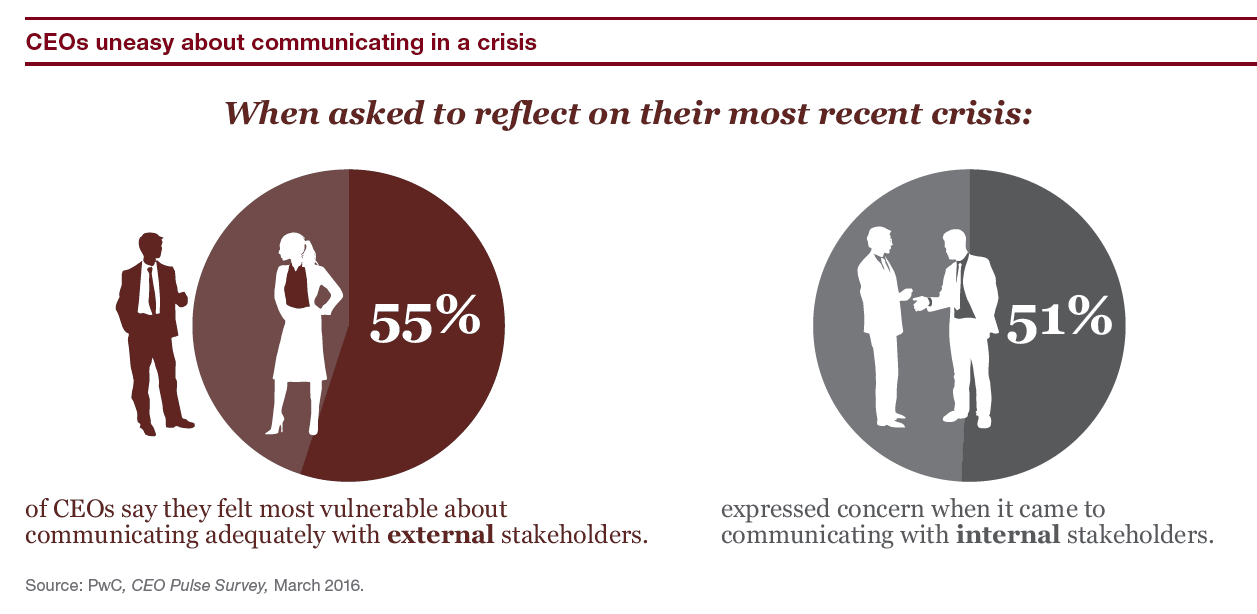

2. Bungled communications. Well-prepared companies may be able to recover relatively quickly from the event that triggered a crisis—whether that’s getting a plant back online or cleaning up an environmental accident. But if the communication about the crisis and the company’s response is mishandled, the impact will reach far beyond an operational problem. That’s when reputation can really be eroded. In a crisis, the media, the public, customers and employees will be demanding information. But it’s tough to provide definitive information about what’s happening when even management isn’t entirely sure of the cause or the status. Compounding that challenge, false stories may circulate through social media. There might also be differences of opinion internally about when management should communicate and what they should say.

In certain high profile cases, politicians or regulators may get involved with inquiries or demands for information. Indeed, congressional committees may call on the CEO to testify before the underlying causes of the crisis are known or fully understood. So CEOs have a tricky balancing act between acknowledging their responsibility and avoiding claims that may arise from sharing information that may be preliminary.

While the company may be focusing on external communications, ignoring internal communications can exacerbate matters. So ensure employees are informed about the crisis itself, that they know where they can get more information if they need it and make sure they know to report all relevant information to a central site.

3. Remembering the rest of the company. It’s easy to get overwhelmed in a crisis. It demands a significant amount of time and energy from the CEO and senior leadership. But losing sight of the ongoing business can make the impact of the crisis worse. Competitors will be watching for ways to profit from a company’s woes. And other more nefarious actors—cybercriminals—may also try to exploit various vulnerabilities, relying on the fact that management is distracted.

Board action: During a crisis, regularly review feedback from inside and outside the company on how well the company is responding.

The CEO is typically the face of the company in a crisis. Companies also depend on their communications executives and often public relations and law firms to help navigate messaging. Law firms can advise on required communications, such as those to regulators, and also offer perspectives on how to ensure that any disclosures the company makes voluntarily don’t expose it to increased liability. Crisis communications experts can guide senior management on a communications strategy, including how frequently to report despite the absence of additional information. People still want updates, even if the answer is, “we don’t know.”

For its part, the board will want to understand the planned approach to communications. Directors should expect to see clear messaging on what has happened, who is accountable, how the company is responding and what will be done to address problems in the wake of the crisis. And they should push back if the communications don’t appear to align with the company’s core values.

While the communications team is developing messages and updates, they—and the board— need to stay on top of how the public and other stakeholders are responding. It’s easy to be caught in an echo chamber without a clear perspective on how the information is being received and processed outside the company.

That means boards should look beyond management for perspectives about the crisis. Directors can follow news and social media channels to stay current, as well as get “sentiment analysis” from outside experts. Directors can also hold executive sessions with these experts just to be sure they’re getting the full picture. The board will need to challenge management and demand course correction if it senses that the messages aren’t working.

While the CEO is typically the main spokesperson, that can present a problem if the CEO’s credibility is badly damaged—particularly if he or she is at the center of the crisis. Such cases often require someone else to step into the spokesperson role. That may be an interim company leader or even the board chair or lead director.

The board should expect to be updated regularly on how the crisis is being handled. During the height of the crisis the briefings could occur daily or more often. That may prompt the board to consider appointing a special committee to help with oversight.

Then there is the rest of the business to consider. Ask which executives are designated to manage the ongoing operations. And make sure they’re getting the resources and support they need. Also challenge whether they understand the full scope of the crisis’ impact on operations. For example, when an earthquake and tsunami hit Japan in 2011, it took some companies an extended period to register how the damage to their suppliers would impact their supply chains.

What role does social media play in a crisis?

Social media has given everyone a public platform, which makes it especially important that someone monitor it during a crisis. Many people turn to Facebook and Twitter first for news when a crisis erupts.

How can companies manage social media chatter, especially in the wake of a crisis? First, policies and procedures do matter, so people need to be trained about what they can and cannot say on social media when representing the company. And it’s important the corporate communications function finds opportunities to use social media productively—to get out messages to the public, customers, employees and their families, and other stakeholders, or to provide updates on how the company is responding to the crisis.

Challenge: The company repeats the same mistakes it made when dealing with past crises.

Once a crisis has passed, people tend to take a breath as they recover and get back to “business as usual.” But unless there’s a thoughtful post-mortem, and adjustments, if needed, to the crisis plan, the company risks repeating any mistakes it made in future crises.

Board action: Discuss lessons learned with management and how crisis management plans will be improved.

Directors will likely want to understand the root causes of the crisis the company has just weathered. This allows the board to weigh in and discuss whether appropriate follow-up actions have been taken.

Management will often lead such investigations. But if management itself seems to be at the heart of the crisis or if the event was significant enough, it may make sense for the board to decide whether an independent investigation is needed. (A natural disaster probably won’t need an independent investigation, for example, unless the crisis management plans were woefully inadequate.) As well as looking at root causes, management should assess what improvements are needed to the company’s crisis plan. Did we have the right people and experts involved? Did our employees know what they needed to do? How strong were our regulatory relationships? Did our communications strategy work? Did we have the information and intelligence we needed to respond? Directors will want to understand what was learned and how crisis plans are changing as a result.

In conclusion…

Knowing the company has a sound crisis plan can give directors greater confidence that management is ready to respond to a future crisis. Since many directors have had to deal with crises in their executive roles, they can use their experience to advise management. The better the plan is, the more likely it will help a company handle a crisis quickly and effectively.

It doesn’t all have to be bad news. Companies that successfully respond to a crisis can ultimately emerge stronger and be viewed more positively by their customers, employees and other stakeholders.

Print

Print