This post is based on a Fried Frank publication by Gail Weinstein, Philip Richter, Warren S. de Wied, Robert C. Schwenkel, Brian T. Mangino, and Scott B. Luftglass. This post is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

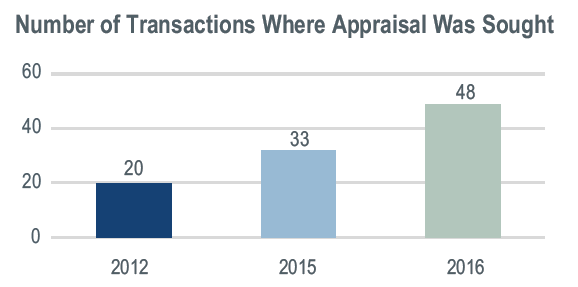

While other M&A-related litigation has decreased dramatically over the past couple of years based on the seminal Corwin and Trulia decisions, there has been a significant uptick in appraisal litigation (notwithstanding amendments to the appraisal statute in 2016 that eliminated de minimis appraisal cases). We note that, nonetheless, appraisal actions continue to be brought in a small minority of M&A transactions.

- Appraisal results. While the court has sometimes relied, solely or primarily, on the merger price, and sometimes on a DCF analysis, to determine appraised fair value, the court has almost invariably found fair value to be significantly above the merger price only in the case of affiliated transactions (i.e., where an affiliated party stands on both sides of the transaction, such as in a controller take-private, majority stockholder squeeze-out, or management buyout). Our updated Delaware Appraisal Chart (with relevant information for all appraisal decisions issued since 2010) appears in the complete publication (available here).

- PetSmart and SWS decisions. In previous publications, we analyze the Court of Chancery’s two most recent appraisal decisions: PetSmart (where the court relied on the merger price notwithstanding that (i) only financial sponsors, and no strategic buyers, submitted bids for the target company, and (ii) the target company experienced significantly improved post-signing financial performance); and SWS (where the court, for only the third time—based on our study of appraisal decisions since 2010—determined fair value to be below the merger price).

- Pending Supreme Court appeals. The Delaware Supreme Court is expected to rule shortly on the appeals of the DFC Global and Dell appraisal decisions. The Supreme Court may endorse the Court of Chancery’s trend toward greater reliance on the merger price to determine fair value where there has been a robust sales process, may instead emphasize the statutory prescription that the court consider “all relevant factors” (and thus should consider a DCF analysis result, even when there has been a robust sales process), or may take some other approach.

Clarification on Unavailability of Corwin Cleansing—“Coercion” and “Unrelated Acts”—Saba Software, Liberty Broadband and Massey Energy

Under Corwin, if the stockholders approve a board action in a “fully informed” and “uncoerced” vote, the stockholder approval “cleanses” any breaches by the directors of their fiduciary duties in connection with the action. Since Corwin was decided in 2015, in every case where the defendants were seeking Corwin cleansing, the Delaware courts have found that the stockholder vote was fully informed and uncoerced—with the only exceptions being the recent decisions in In re Saba Software Stockholder Litigation (April 11, 2017), Sciabacucchi v. Liberty Broadband Corporation and Charter Communications, Inc. (May 31, 2017), and In re Massey Energy Co. Derivative and Class Action Litigation (May 4, 2017).

Key Points

- Corwin, Saba, Liberty and Massey establish five categories under which Corwin “cleansing” may not be available:

- Inadequate disclosure—the stockholder vote was not “fully informed” (Corwin);

- “Affirmative coercion”—stockholders were threatened with retribution of some type if they did not approve the proposed action (Corwin);

- “Situational coercion”—due to a situation created by the board, the stockholders had no practical alternative but to vote for the proposed action (Saba);

- “Structural coercion”—the stockholder vote to approve an action was tied to a stockholder vote on an unrelated action (Liberty); and

- “Unrelated acts”—the defendants sought to cleanse breaches of fiduciary duty with respect to actions the directors took that were unrelated to the action that the stockholders approved (Massey).

- These decisions do not appear to undercut the courts’ general approach of broad applicability of Corwin. Indeed, these decisions appear to confirm the trend of post-Corwin decisions that indicate that Corwin cleansing of non-controller stockholder-approved transactions is likely to be precluded only in unusual and egregious circumstances.

- “Coerced” votes are likely to be rare. “Affirmative coercion” occurs rarely. The concepts of “situational coercion” and “structural coercion” appear to have been developed in Saba and Liberty based on the unusual and egregious facts particular to those cases.

- The concept of “unrelated acts” appears to be simply a commonsense clarification. As explained by the court in Massey, the concept simply confirms that stockholder approval of one action will not cleanse every historical action by directors that led up to that action (although, we note, it does raise the issue of what the parameters will be with respect to how “related” an action must be to the stockholder-approved action for it to be included within the ambit of Corwin cleansing).

Saba Software: “Situational coercion” resulting from the board putting stockholders in a position of having to approve a transaction because it is the better of two bad alternatives. The SEC had determined that, over several years, Saba Software, Inc. had engaged in fraud; and that, for several years thereafter, despite SEC orders to do so, and without explanation, the board had continuously failed to restate its financial statements to account for the fraud, as a result of which the company’s stock was deregistered and, the plaintiffs alleged, the company was sold at a fire-sale price. The defendants asserted that any breaches of fiduciary duty in connection with entering into the $30 billion merger had been cleansed, under Corwin, by the stockholder vote approving the merger. The court held, at the motion to dismiss stage, that the stockholder vote may have been neither “fully informed” nor “uncoerced.” Vice Chancellor Slights acknowledged that there had been no “affirmative coercion”—that is, no “affirmative action by the fiduciary in connection with the vote that reflected some … promise of retribution that would place stockholders who rejected the proposal in a worse position than they occupied before the vote.” However, the Vice Chancellor rejected the defendants’ contention that only “affirmative coercion” would preclude Corwin cleansing. Rather, the Vice Chancellor stated, a coercive situation created by board action also would preclude Corwin cleansing.

The Saba stockholders may have faced “situational coercion,” the court stated, as, based on the board’s actions (i.e., the fraud, followed by the board’s continued and unexplained failure to restate the company’s financial statements), the stockholders had only a “Hobson’s choice” to “choose between keeping their recently deregistered, illiquid stock or accepting [the depressed] Merger price.” The situation, created by the board, left the stockholders with “no practical alternative but to vote in favor of the Merger.” The situation was coercive, the court explained, because the essence of “coercion” is putting stockholders in a position where their vote will necessarily be based on factors other than the economic merits of the action being voted on. While Saba involved unusual and egregious facts that were central to the court’s decision, a board should be attuned to the possibility of “situational coercion” where the stockholders have what could be viewed as a “Hobson’s choice” between an unattractive proposed transaction and only an even more unattractive alternative.

Liberty: “Structural coercion” resulting from the board’s tying together two unrelated actions. In Liberty, the stockholders had approved two proposed acquisitions (the “Acquisitions”) that were conditioned in part on stockholder approval of an issuance of equity to and a proxy voting arrangement with the company’s major stockholder (the “Equity Arrangements”). While the Equity Arrangements were used to partially finance the Acquisitions, they were “not integral” and were “extraneous” to the Acquisitions, according to the court, as the company “easily” could have financed the Acquisitions without them. By conditioning the Acquisitions on stockholder approval of the Equity Arrangements, the court reasoned, the board left the stockholders in a situation where, when they voted on the Equity Arrangements, they were not voting based on the merits of the Equity Arrangements but on the merits of the Acquisitions. In other words, to obtain the benefits of the Acquisitions, the stockholders had no practical choice but to approve the Equity Arrangements. While there was “nothing inherently nefarious” about the Equity Arrangements and “directors can act within their business judgment in the structuring of a transaction or the issuance of equity,” Vice Chancellor Glasscock wrote, “[t]he threshold question here is, assuming that wrongdoing by the Defendants inheres in [the Equity Arrangements], is it nonetheless cleansed by the ratifying vote of the stockholders?” The Vice Chancellor concluded: “Under the unique circumstances here, I find the answer is no.”

While the facts in Liberty were “unique,” a board should be attuned to the possibility of structural coercion where, due to action taken by the board to tie together two non-integral transactions, the stockholders have to approve the proposed transaction to obtain the benefit of the other transaction—particularly if, as in Liberty, the proposed transaction involves benefits to an insider to the possible detriment of the other stockholders. Moreover, we note, there may not have been any vote required for the board to effect the Equity Arrangements—indicating that the vote was imposed for the purpose of obtaining Corwin cleansing of the unrelated action.

Open issue as to the parameters of “structural coercion.” Left for further judicial development is the issue as to when two actions are sufficiently related to be tied together by a board without a court considering the vote to have been structurally coerced. If stockholders vote on two actions, is the second action necessary for the consummation of the first? If not, what is the basis on which the board determined to tie the two actions together? Notably, in Liberty, there was evidence that the Acquisitions could have been financed in any number of conventional ways, without the Equity Arrangements—thus, the Equity Arrangements were beneficial to a corporate insider but not necessarily beneficial to the corporation.

Vice Chancellor Glasscock wrote in Liberty:

I understand that some method of financing is inherent in every transaction, and typically an informed [stockholder vote] in favor of the transaction ratifies the directors’ actions with respect to financing. Certainly, if a deal cannot proceed absent adoption of a particular financing, an informed vote for such a transaction is cleansing with respect to the financing method chosen. The Complaint here alleges that the directors separately, and for reasons unrelated to the business interest of [the Company], chose to issue equity to an insider, then coerced acceptance of the inequitable issuance by tying it to approval of the underlying transaction.

According to the Vice Chancellor, the Liberty directors chose to finance the Acquisitions with the Equity Arrangements even though, according to the plaintiffs, the Acquisitions could have been financed “in any number of ways.” A plaintiff’s pleading that a transaction could have been “easily” financed in other ways, the court stated, “if merely conclusory, might be unpersuasive to implicate coercion.” In this case, however, the court wrote, “the contents and omissions of the definitive proxy statement are telling.” According to the court, the pleadings and record indicated that the board did not determine that the Acquisitions “could be consummated only via the [Equity Arrangements],” and the directors “did not seek or receive a fairness opinion” relating to the issuance of equity to its major stockholder standing alone. Rather, “[w]hat the Complaint and proxy do disclose is that [the major stockholder] wished to make an additional equity investment in [the Company], and communicated that to the Defendant directors, who then structured the [Equity Arrangements]. These are the facts from which I must infer whether the [Equity Arrangements] are an integral part of the Acquisitions, or interested separate transactions for which the Defendant directors coerced stockholder approval….” “Fiduciaries cannot interlard such a vote with extraneous acts of self-dealing, and thereby use a vote driven by the net benefit of the transactions to cleanse their breach of duty.” Otherwise, “fiduciaries could attach self-dealing riders to any transaction under consideration, and avoid being held to account by a favorable stockholder vote. That is not equity; it would represent, not a cleanse, but a white-wash.”

Massey: “Unrelated acts” to the stockholder-approved action are not cleansed under Corwin. The plaintiffs challenged directors in connection with their approval of a merger that was allegedly necessitated by the directors’ having breached their oversight duties over many years—which failure of oversight, according to several investigations, led to systematic, widespread violations of mining safety regulations, culminating in the worst mining disaster in the U.S. in forty years, with the loss of numerous lives and criminal convictions for the CEO and other Massey executives. The court granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss the action based on standing issues—but the decision is most notable for the court’s discussion relating to Corwin. Chancellor Bouchard stated that, notwithstanding stockholder approval of the merger, the alleged breaches by directors of their fiduciary duties with respect to historic director actions that were “unrelated” and “extraneous” to the merger could not be “cleansed” under Corwin. According to the court, the director conduct about which the plaintiffs complained occurred well before and was not sufficiently proximately related to the merger. Chancellor Bouchard wrote that Corwin “was never intended to serve as a massive eraser, exonerating corporate fiduciaries for any and all of their actions or inactions preceding their decision to undertake a transaction for which stockholder approval is obtained.”

Delaware Supreme Court, Reversing Chancery Court, Interprets Post-Closing Purchase Price Adjustment “True Up” Narrowly, Based on the Specific Factual Context—Chicago Bridge v. Westinghouse

In Chicago Bridge & Iron Company N.V. v. Westinghouse Electric Company LLC (June 28, 2017), the Delaware Supreme Court interpreted a purchase agreement net working capital “true up” as a “narrow, subordinate, and cabined remedy.” The buyer contended that the seller’s post-closing net working capital calculations were flawed because the seller’s historical accounting practices in preparing the target company’s financial statements were not compliant with GAAP.

The seller argued that, under the purchase agreement, the buyer’s only remedy for breaches of representations and warranties had been a refusal to close (which the buyer had foregone)—and that, therefore, the buyer could not properly request that the dispute resolving auditor make a determination with respect to claims about GAAP compliance of the financial statements. The Supreme Court ordered that the Court of Chancery “enjoin [the buyer] from submitting to the [auditor] or continuing to pursue” the claims that were based on the historical accounting issues. The only claims that could be submitted and pursued, the Supreme Court held, were those “based on changes in facts and circumstances between the signing and closing.”

As a result of the decision, the buyer’s $2 billion claim with respect to the post-closing purchase price adjustment was reduced to less than $70 million. The Supreme Court emphasized that the decision was grounded in the specific factual context of the case. The first sentence of Chief Justice Strine’s opinion reads: “In giving sensible life to a real-world contract, courts must read the specific provisions of the contract in light of the entire contract.”

Key Points

- The decision confirms that a provision requiring a “true up” at closing of net working capital for purposes of determining a purchase price adjustment will generally be considered to be a narrow remedy, relevant only to changes occurring between signing and closing—and cannot be used as an end-run around purchase agreement provisions that limit liability for breaches of representations and warranties.

- The decision underscores, however, that the specific language of a true up provision, the other provisions of the purchase agreement, and the overall context of the deal, will influence the court’s interpretation of the breadth of the claims that can be made under the true up.

Background. CB&I Stone & Webster, Inc. (the “Company”), a subsidiary of Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. (the “Seller”), had been building nuclear power plants, in partnership with Westinghouse Electric Company (the “Buyer”). As delays and cost overruns mounted, the relationship became “contentious.” To resolve their differences, the Seller agreed to sell the Company to the Buyer, with the Buyer paying zero dollars as a purchase price but assuming all of the liabilities of the Company. (Cost overruns at these projects, in the billions of dollars, ultimately forced the Buyer into bankruptcy in March 2017—also threatening the financial viability of the Buyer’s parent, Toshiba Corp.)

The Purchase Agreement provided as follows:

- True Up. The purchase price of zero was based on a target net working capital amount of $1.174 billion. The Agreement provided for a “True Up” at closing, and a post-closing purchase price adjustment to the extent that actual net working capital at closing varied from the target amount. The Seller was required to continue to run the Company in the ordinary course of business until closing.

- Liability Bar. The Agreement provided that the Buyer’s sole remedy if the Seller breached its representations and warranties was to refuse to close; that the Seller would have no liability for monetary damages post-closing (the “Liability Bar”); and that the Buyer would indemnify the Seller for all post-closing claims or demands against, or liabilities of, the Company.

- Dispute Resolution. Any dispute over the post-closing purchase price adjustment was to be submitted to an independent auditor (the “Auditor”)—who was to act “as an expert, and not as an arbitrator”; to issue a decision, in the form of a “brief written statement,” within 30 days; and to rely on the parties’ written submissions as the sole basis for its decisions.

The Court of Chancery ruled in favor of the Buyer, reasoning that the mandatory dispute resolution provision in the Purchase Agreement meant that all disputed issues relating to the post-closing adjustment were to be submitted to the Auditor. The Supreme Court reversed, finding that the lower court decision—which would have permitted a “wide-ranging” challenge to the Company’s historical financial statements—was inconsistent with (i) the Liability Bar provision of the Purchase Agreement; (ii) the structure of the True Up, which reflected that it was a “narrow,” “confined” remedy that related to the period between signing and closing; and (iii) the general tenor of the deal and other terms of the Purchase Agreement, which indicated an intention to provide a “clean break” for the Seller.

Discussion

The Supreme Court viewed the True Up as a narrow remedy that could not be used as, in effect, an end run around the Liability Bar. In the Supreme Court’s view, the Buyer’s claims were, “in essence, claims that [the Seller] breached the Purchase Agreement’s representations and warranties….” The claims “therefore are foreclosed by the Liability Bar,” the Supreme Court held. The Court of Chancery decision, the Supreme Court wrote, by “reading the True Up as unlimited in scope and as allowing [the Buyer] to challenge the historical accounting practices used in the represented financials, … rendered meaningless the Purchase Agreement’s Liability Bar.” The Buyer’s sole remedy if the financial statements were not GAAP-compliant was to refuse to close, the Supreme Court stated—which the Buyer had chosen not to do.

The Supreme Court confirmed that the main role of a true up, as a general matter, is to account for changes in the target company’s business between signing and closing. The Supreme Court rejected the Court of Chancery’s interpretation of the True Up as “providing [the Buyer] with a wide-ranging, uncabined right to challenge any accounting principle used by [the Seller].” Rather, the Supreme Court wrote, the True Up, “[w]hen viewed in proper context, … is an important, but narrow, subordinate, and cabined remedy available to address any developments affecting Stone’s working capital that occurred in the period between signing and closing.” The Supreme Court reviewed that generally the purpose of a true up is to “maintain the underlying economics of the parties’ bargain”—in this case, to ensure that the Seller would continue to operate the Company “as though it were still its own business, but without worrying that pursuing normal construction operations would benefit [the Buyer] to [the Seller’s] own detriment”; to protect the Buyer against the Seller or the Company “suddently shift[ing] course in how it chose to treat [the Company] from an accounting perspective”; and to protect the Buyer against “end[ing] up worse off than it was at signing” if “[the Seller] didn’t follow through with the construction program or if the Buyer and the utilities paid a bunch of their bills….”

The Supreme Court viewed the language of the True Up as supporting the view that it could not be used to challenged past accounting practices. The Supreme Court noted that the True Up “emphasizes that net working capital should be determined in a manner consistent with GAAP, consistently applied by the seller in preparation of the company’s financial statements.” Other pertinent language in the agreement also requires consistency with past practices and with “the basic idea that the True Up is used to set a Final Purchase Price based on developments after the initial price of zero was set.” Thus, the Court concluded, “the True Up was tailored to address issues that might come up if [the Seller] tried to change accounting practices midway through the transaction or if it stopped work on the projects, rather than continue to invest as expected [and as required by the covenant to run the business in the ordinary course until closing].” The parties expectation, according to the Court, was that, “at closing, [the Buyer] would get [the Company] and [almost certainly would] have to make a payment to [the Seller], [under the True Up,] to account, for example, for the expectation that [the Seller] would make substantial capital expenditures before closing so [the Company]’s construction projects could continue.”

The Supreme Court viewed the limited role of the Auditor as confirming the narrow role of the True Up. Moreover, the Court noted, the structure of the dispute settlement provision confirmed that the True Up was to have a “subordinate and confined purpose.” The settlement procedure required a brief written statement by the Auditor, issued within the “expedited timeframe” of 30 days, with reliance only on the parties’ written submissions. The Court stated:

[T]he reason parties can hazard having an expert decide disputes in this blinkered, rapid manner is because when considering claims under the True Up, the expert is addressing a confined period of time between signing and closing using the same accounting principles that were the subject of due diligence and contractual representations and warranties, and thus formed the foundation for the parties’ agreement to sign up and close the transaction.

The Supreme Court viewed the overall context of the deal as supporting its interpretation of the True Up as a narrow remedy. “The basic business relationship between parties must be understood to give sensible life to any contract,” the Chief Justice wrote. The zero purchase price, assumption of all liabilities by the Buyer, Liability Bar, and other provisions of the Purchase Agreement, and the genesis of the deal as a resolution of the various differences between the parties in running the construction projects, indicated an intent to provide the Seller with a “clean break,” the Supreme Court wrote. The “essence of the deal” was that “[the Seller] would deliver [the Company] to [the Buyer] for zero dollars up front consideration and, in return, would be released from any further liabilities connected with the projects.” Not only would the Buyer indemnify the Seller against future liabilities, the Court wrote, but closing was contingent on the Seller receiving releases from the utility company that would operate the plants when they were completed. The Court concluded: “The key provisions of the Purchase Agreement show and the business context they highlight demonstrates, [the Buyer]’s view that the Purchase Agreement gave it a free license to re-trade the core common basis of the exchange is beyond strained; it involves a rewriting of the contract embodying that exchange.” Moreover, the Court noted, the accounting practices about which the Buyer complained were known to the Buyer prior to its entering into the Purchase Agreement and were reflected in the very financial statements on which the Buyer relied when deciding to enter into the deal.

Justice Strine characterized “the sum total of [the Buyer’s] logic” to be as follows:

Based on challenges to large items included in the [Seller’s] financials that [the Seller] represented were GAAP compliant, which [the Buyer] knew about before closing, and which [the Buyer] did not use as a basis not to close, [the Buyer] now says that it should keep [the Company], which it got for zero dollars, and be paid by [the Seller] over $2 billion for taking it!

Practice Points

- It should be kept in mind that a court’s interpretation of a contract provision will be influenced not only by the language of the provision and the contract as a whole, but also the overall history and context of the deal. Clarity in drafting is key, as unambiguous language will be applied as written.

- Although most of the issues in Chicago Bridge arose because of the Liability Bar in the purchase agreement, the decision is a reminder of the need to draft a true up with clarity and precision. Based on Chicago Bridge, parties should consider stating whether a closing true up is intended to cover only changes occurring in the business between signing and closing (and, if so, which changes). Attaching hypothetical examples can be helpful.

- Parties should be mindful that the timeframe and other parameters set forth for a settlement process may influence the court’s view of the breadth of a settlement dispute provision purporting to cover “all” disputes. Parties should consider stating whether the structure of the settlement process is or is not reflective of the parties’ intent with respect to the substantive breadth of the true up.

The complete publication, including appendix, is available here.

Print

Print