Matthew Schoenfeld is a Portfolio Manager at Burford Capital. This post is based on a recent paper by Mr. Schoenfeld, and is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

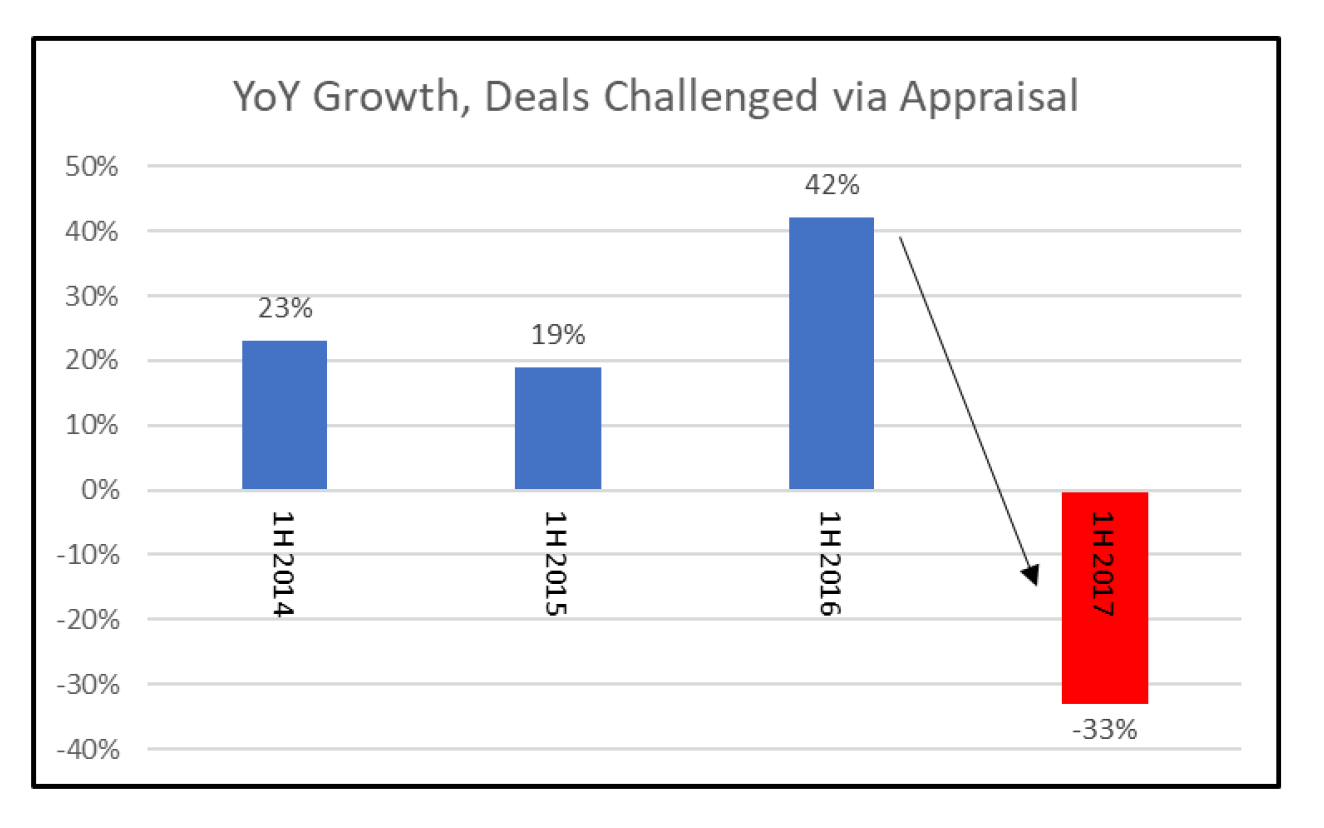

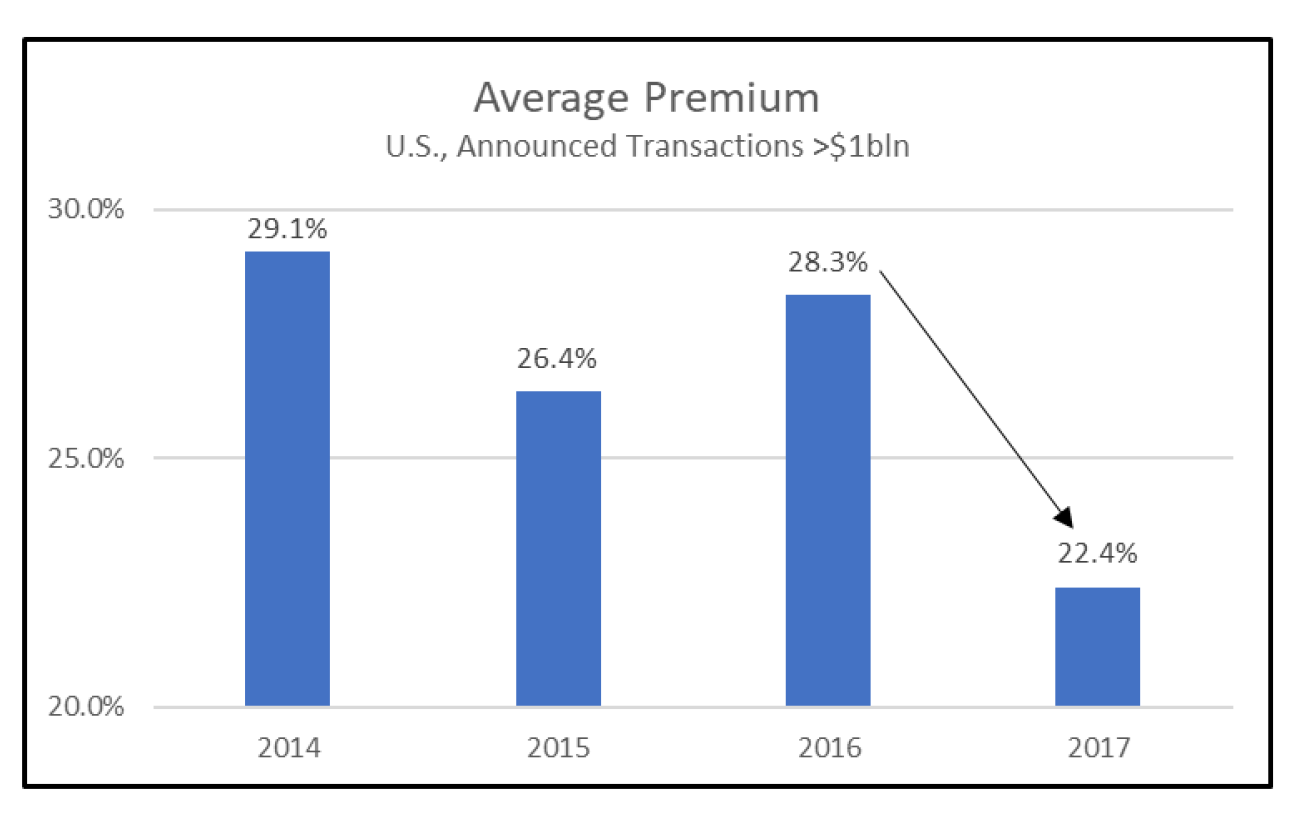

This post considers the preliminary results of an ongoing effort to discourage appraisal litigation. In the year since the August 2016 reforms to the Delaware appraisal statute, Chancery has issued a slew of at-or-below merger price appraisal opinions in cases such as Clearwire and PetSmart, while simultaneously pinioning fiduciary litigation by reiterating the principles of Corwin. The result—as one would expect when costs are raised and benefits are reduced—has been that fewer deals are being challenged via appraisal: In 1H 2017, the number of deals challenged fell by 33%. Those who successfully advocated for curbs on the practice had argued that appraisal claims lowered deal premia by incenting buyers to withhold top dollar, thereby hurting non-appraising shareholders. On their view, curtailment of appraisal should have sent premia upwards. But year to date the average U.S. target premium of 22.4% is the lowest of any year in recent history. The average target premium in 2Q 2017 of 19.3% was the single-lowest of the fifty prior quarterly observations; thus far, 3Q 2017, at 19.6%, is tracking as the second-lowest. Amid the pronounced decline in merger premia, change-in-control payouts have expanded as a percentage of transaction value.

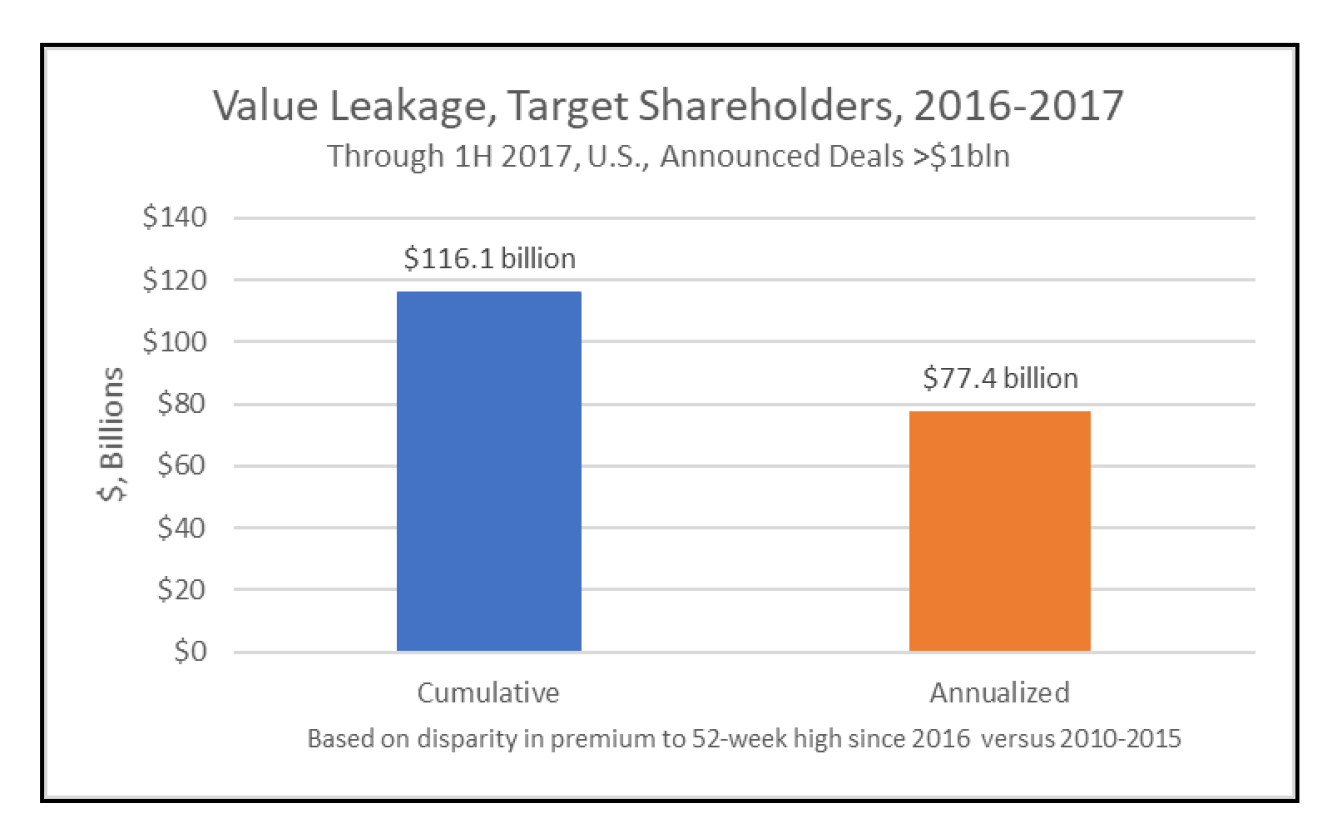

When analyzed in concert with other measures indicative of agent rent-seeking—such as target premium to 52-week high over varying periods—the evidence points to a substantial transfer of value from target shareholders to selling CEOs, who have adapted to an environment rendered more permissive by the weakening of the shareholder litigation “check” that had formerly restrained such behavior.

As Shareholder Litigation Weakens, M&A Premiums Fall

It has been a year since the August 2016 reforms to the Delaware appraisal statute—intended to make appraisal less economically attractive—took effect. Over that period, Chancery has further clamped down on shareholder litigation using a two-pronged approach. It has issued a slew of at-or-below merger price appraisal opinions in cases such as Clearwire and PetSmart, while simultaneously pinioning fiduciary litigation by reiterating the principles of Corwin—a 2015 decision that limited the number of transactions subject to enhanced scrutiny under Revlon—in cases such as Singh v. Attenborough (May 2016), OM Group (October 2016), and Volcano (December 2016).

The result—as one would expect when costs are raised and benefits are reduced—has been that fewer deals are being challenged via appraisal. During the first-half of 2017, 18 deals were challenged, one-third fewer than the 27 challenged during the same period in 2016. One might argue that a year-over-year decline in M&A is responsible for the fall—but this seems a bit beside the point given that the 33% year-over-year contraction in such claims (from 27 to 18) during the first half of 2017 compares to a more than 20% annual growth rate from 2013-2016. To be sure, M&A volume is down in 1H 2017. But declines in M&A volume hadn’t tempered appraisal claims in recent years. Namely, in 1H 2016, M&A was also down, but the number of deals challenged grew by 42%.

So what has happened to deal premia? Those seeking curtailment of the appraisal remedy in Delaware argued that the presence of appraisal-seeking holdouts induces buyers to withhold top dollar, thereby harming non-appraising shareholders. That is, acquirers would maintain dry powder ex-ante for payments to purported rent-seekers in the form of appraisal arbitrageurs ex-post. In the words of one highly respected deal lawyer: “This (appraisal) risk is one that troubles buyers of Delaware companies, especially private equity firms, preventing them from paying the highest prices they can pay…” On their view, curtailment of appraisal should have sent premia upwards as buyers used more of their powder for bids.

But year to date the average U.S. target premium of 22.4% is the lowest of any year since at least 2005 (the extent of the Bloomberg data set utilized). In fact, the target premium in 2Q 2017 of 19.3% was the single-lowest of the fifty quarterly observations in the data set dating to 1Q 2005. What’s more, if the quarter to date average premium for 3Q 2017 holds, it will be the second-lowest quarterly observation in the data set at 19.6%.

The devil’s advocate might say that flagging premiums for target shareholders in 2017 can be attributed to the late-cycle nature of the current expansion and already-inflated equity valuations. Perhaps, although 2015 and 2016 could have been described similarly, and even 2007—the archetypal late-cycle sample—yielded an average premium of 26%, about 360bps better for target shareholders.

Parachutes Trump Paranoia

CEOs typically have substantially lower personal reservation prices in sell-side M&A than do their respective disinterested minority shareholders. This reservation price disparity stems not only from CEOs’ ability to internalize 100% of their CIC package while externalizing most “costs” of a lower transaction price, but also from any additional rents they are able to extract—via transaction-related bonuses or ex-post Parachute augmentations—at the expense of disinterested shareholders. The threat of appraisal, and resultant discovery, can serve as a check on such rent-seeking value transfers.

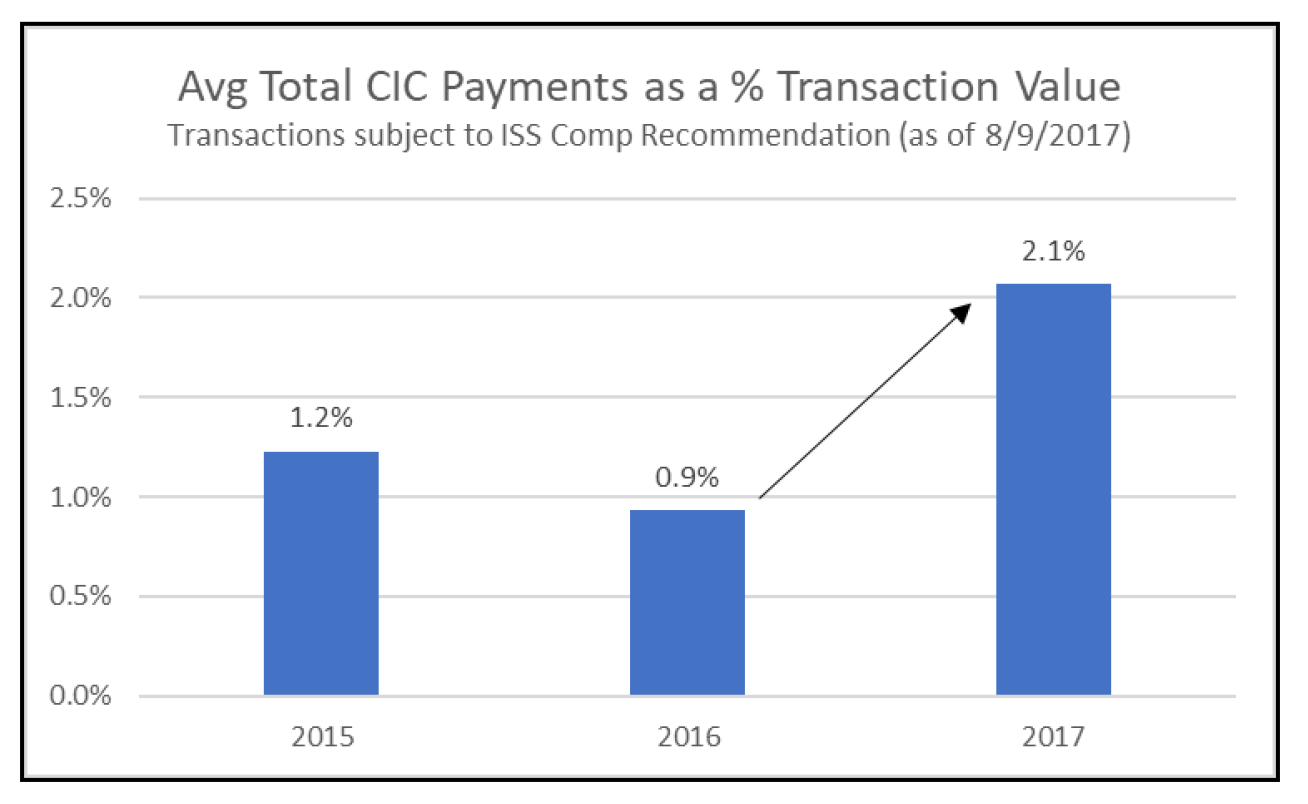

Amid the recent enfeeblement of germane shareholder litigation, it is perhaps not surprising then that as premiums have fallen, Parachutes and related bonuses have burgeoned: In 1H 2017, the average named executive officers (NEO) Change-in-control package (CIC), or “Golden Parachute,’ in deals substantial enough to warrant an ISS recommendation, was 2.1% of transaction equity value, up 52% from its 2012-2016 average of 1.36%. And it doesn’t appear that a handful of outlier transactions are responsible for the surge—the median 1H 2017 Parachute was 1.83% of transaction value, nearly triple the 2012-2016 median of 0.69%.

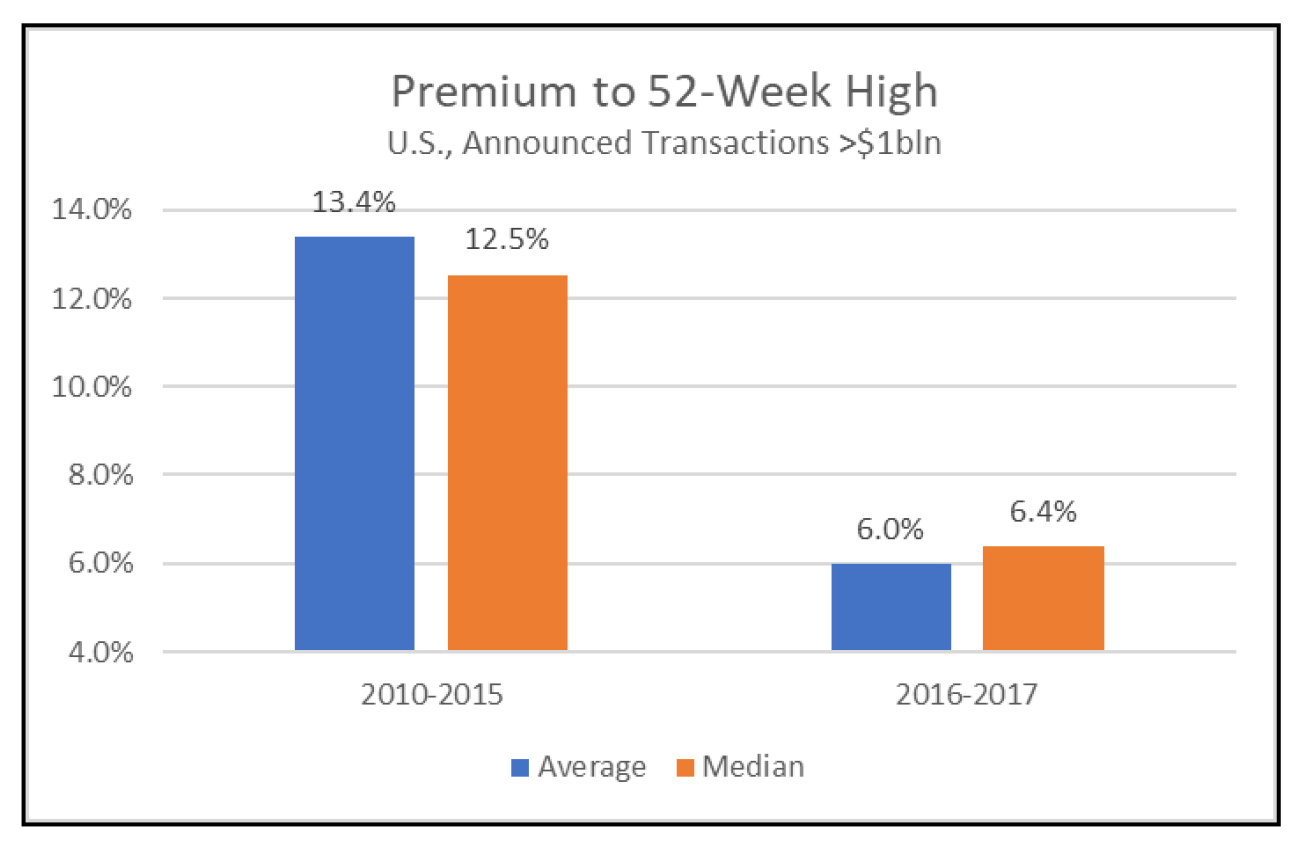

Perhaps the best way to measure the impact of this rent-seeking, from shareholders’ perspective, is via target M&A premium to trailing 52-week high. This measure is better suited to gauge the value siphoned off by rent-seeking—versus simple pre-announcement, T-1, premium—because it tends to eliminate noise engendered by CEOs “talking-down” share prices, or “sandbagging,” ahead of deal announcement to “create space’ for an acceptable T-1 premium and thus avail themselves of CIC payouts.

Per below, from 2010-2015, the average and median premium to 52-week high were 13.4% and 12.5% respectively—but since 2016, as shareholders’ ability to challenge transactions waned, the average and median premium to 52-week high have dropped to 6.0% and 6.4%, respectively:

The notion that CEOs—when afforded the opportunity—will sacrifice merger premia to secure Parachute payouts is not a novel one—a study of 851 acquisitions from 1999-2007 found that:

A one standard deviation increase in parachute importance (relative size) raises the probability of merger completion by 6.9 percentage points but lowers the takeover premium by 2.6 percentage points…Our results are consistent with the following interpretation: as the importance of the parachute to target CEOs increases they negotiate an offer up to their own reservation premium …

The fact that this underlying tendency has recently shifted into overdrive—and adopted a more value-destructive form—isn’t probative of unique avarice among today’s CEOs. They’re simply rational actors adapting to an environment rendered more permissive by the weakening of the shareholder litigation “check” that had formerly restrained such behavior.

A Billion Here, a Billion There, and Pretty Soon You’re Talking Real Money

Had the average premium to 52-week high remained at historical norms since 2016, target shareholders would have received an additional $116.1 billion in cumulative merger consideration, or an additional $77.4 billion per year on an annualized basis:

It’s important to note that CEO rent-seeking need not necessarily involve an explicit “bribe” or quid pro quo via transaction bonus or continuing employment. For CEOs with relatively substantial CIC packages, this prospective payout may not require additional “sweeteners” to incentivize the pursuit of a value-destructive sale, at least from the perspective of the disinterested shareholder.

Granted, this temptation to “cash-in” by consummating even a below-fair-value sale might be tempered by the monitoring capabilities of independent members of a respective firm’s board of directors.

Unfortunately, there is compelling evidence that even this restraint has been substantially eroded.

(Re)Defining the “Self-Interested” Transaction: Reasonable Person Test

Considering the accelerating imbalances delineated above, it may be worth re-evaluating the definitional lens of the “self-interested” transaction.

DFC Global has, of late, become archetypal of the “pristine” sales process, devoid of self-interest—per Chancery, and as cited by the Delaware Supreme Court, “There was no hint of self-interest that compromised the market check,” and “The deal did not involve the potential conflicts of interest inherent in a management buyout or negotiations to retain existing management—indeed, Lone Star took the opposite approach, replacing most key executives.”

Now, for a moment, consider the lens of DFC Global’s then-CEO—who stood to receive a $17.1 million Golden Parachute payout, more than 1,200% his trailing-twelve-month cash compensation, but only if a sale of the company was consummated. The size of his payout varied little based on the price at which the company was sold—just 21% of the Parachute was equity-derived and thus sensitive to transaction price; the remaining 79%, or $13.5 million, consisted of direct cash severance—but it disappeared entirely if he failed to consummate a sale. He presumably had a prominent role in deciding upon an implicitly evolving reservation price during the pendency of the sales process—which lasted two years and which could continue only based on the prospect of exceeding that very reservation price.

Would a reasonable person believe this process to have been devoid of self-interest?

Amid weakened shareholder litigation, dipping premiums, and ever-larger Parachutes, this question should no longer be confined to MBOs and controlling-shareholder squeeze-outs. Indeed, even the “pristine” might be fair game.

The complete paper, including footnotes, is available for download here.

Print

Print