Subodh Mishra is Executive Director at Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. This post is based on a co-publication by ISS and the Investor Responsibility Research Center Institute. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here).

Few business-related topics provoke more passionate discussions than shareholder activism at specific companies. Supporters view activists as agents of change who push complacent corporate directors and entrenched managers to unlock stranded shareholder value. Detractors charge that these aggressive investors force their way into boardrooms, bully incumbent directors into adopting short-term strategies at the expense of long-term shareholders, and then exit with big profits in hand.

Lost in this heated long- versus short-term debate is the significant, real-time impact that such activism has on corporate board membership and demographics. ISS identified a recent surge in its evaluation of refreshment trends at S&P 1500 firms between 2008 and 2016 (see Board Refreshment Trends at S&P 1500 Firms, published by IRRCi in January 2017). This accelerated boardroom turnover coincided with an increase in activists’ success in securing board representation, particularly via negotiated settlements. A recent study of shareholder activism by Activist Insights pegged activists’ annual U.S. boardroom gains at more than 200 seats in 2015 and 2016. While a significant portion of this activism was aimed at micro-cap firms, threats of fights have become commonplace even at S&P 500 companies in recent years.

Despite activists’ recent boardroom gains, little attention has been paid to the influence of activism on broader board refreshment trends. Anecdotal media coverage, often fanned by anti-activist communications strategies, still tends to myopically focus on two long-standing dissident nominee stereotypes: the still-wet-behind-the-ears, 20- or 30-something-year-old hedge fund analyst, and the older, male, over-boarded crony of the fund manager.

These long-standing stereotypes appear to be outdated as activism has entered an era in which most dissident nominees have attenuated ties to their hedge fund patrons. The experience, qualifications, attributes, and skills of dissident nominees can appear indistinguishable from those of the incumbent directors whom they seek to supplant. Nominees’ backgrounds and experiences can become even more interchangeable with those of incumbent directors when the latter transfuse their own ranks with new blood during, or in anticipation of, an activist campaign. This heightened competition can leave shareholders with a bounty of fresh-faced, highly-qualified, independent candidates on both nominee slates. Highlighting this narrowing divide, dissidents’ “hand-picked” nominees have been known to reject their sponsors’ wishes and strategic plans (witness Elliott Management’s first tranche of candidates at Arconic, who were seated via a settlement, opposing the hedge fund’s second attempt to gain board seats). Similarly, nominees selected by incumbent directors to face off against dissident candidates sometimes end up endorsing the very shifts in strategic direction that they were recruited to fend off (witness the DuPont board’s “victory” over Nelson Peltz’s Trian Partners, followed by board-recruited director-turned CEO Ed Breen’s advocacy of a Peltzian-style breakup of the company).

To close this board refreshment information gap, IRRCi asked ISS to explore the broader impact of activism by focusing on nominees—regardless of the entity that backed them—and the impact of dissident campaigns on boards.

Methodology

The complete publication (available here) examines the impact of public shareholder activism on board refreshment at S&P 1500 companies targeted by activists from 2011 to 2015. Public shareholder activism refers to any shareholder activism that (1) occurred between Jan. 1, 2011 and Dec. 31, 2015, and (2) was publicly disclosed. The study period concludes in 2015 so that data for a full calendar year following activist campaigns could be analyzed. Data was captured as of the shareholder meeting dates.

Part I examines individual dissident nominees on ballots (whether they ultimately joined the board or not) in proxy contests, directors appointed via settlements with activist shareholders, and directors appointed unilaterally by boards in connection with shareholder activism.

Part II examines changes to board profiles made in connection with public shareholder activism.

Data was captured for all S&P 1500 directors with less than one year of tenure at meetings scheduled to be held between Jan. 1, 2011 and Dec. 31, 2015. The directors were then assigned to one of four classifications:

- All dissident nominees on ballots in proxy contests;

- Directors appointed or nominated by incumbent boards through publicly-disclosed settlements with activist shareholders;

- Directors appointed or nominated unilaterally by incumbent boards in connection with public shareholder activism; and

- Directors appointed or nominated prior to and not in connection with public shareholder activism.

If a definitive proxy contest was settled, directors added to the board as a result of the settlement were assigned to classification two.

Data for directors assigned to classification four was excluded, as it did not relate to the impact of public shareholder activism on board refreshment during the study period.

In Part II, board profile changes were assessed through a comparison of target boards in the year prior to shareholder activism and target boards in the year following shareholder activism. For example, there was shareholder activism at J. C. Penney in connection with the company’s 2011 annual meeting. The measure of change was therefore based on a comparison of the board profiles at the company’s 2010 and 2012 annual meetings. In cases where there were two or more consecutive years of shareholder activism, board profile changes were assessed through a comparison of target boards in the year prior to the first year of shareholder activism and target boards in the year following the final consecutive year of shareholder activism. For example, there was shareholder activism at Juniper Networks in both 2014 and 2015. The measure of change was therefore based on a comparison of the board profiles at the company’s 2013 and 2016 annual meetings.

Part II examines year-over-year trends. In these cases, study companies with two or more consecutive years of shareholder activism were excluded. Study companies were grouped by market-cap segments, i.e. S&P 500 (large-cap), S&P 400 (mid-cap), and S&P 600 (small-cap). Study companies that changed indexes over the course of the study were excluded from segment-level comparisons.

In Part II, references to changes in average director age and average director tenure at study companies (excluding those discussed in isolation) refer to averages of average company-level data. Company-level data provided average age and tenure for each specific company. For references to average age and tenure at study companies, these data points were calculated by averaging the company-level (rather than director-level) data points.

Key Findings

Part I: Individual Director Demographics

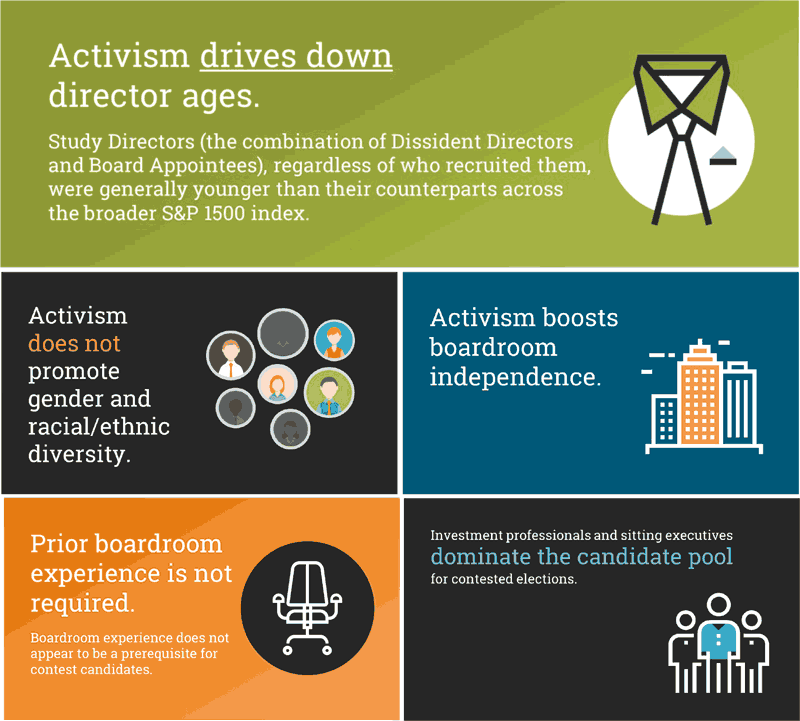

Snapshot: Public shareholder activism generally leads to younger, more independent, but less diverse, board candidates who had previous boardroom experience and relevant professional pedigrees. Typically activists favor nominees with financial experience and incumbent boards favor nominees with executive experience.

Activism drives down director ages. Dissident nominees and directors appointed via settlements (hereinafter Dissident Directors) were younger, on average, than directors appointed unilaterally by boards (hereinafter Board Appointees) in connection with shareholder activism. Study Directors (the combination of Dissident Directors and Board Appointees), regardless of who recruited them, were generally younger than their counterparts across the broader S&P 1500 index. While Dissident Directors generally reflected a wider range of ages, insurgent investors and incumbent boards both favored individuals in their fifties when picking candidates. This preference for nominees in their fifties aligns with practices in the broader S&P 1500 index over the same period.

Activism does not promote gender diversity. Less than ten percent of Study Directors were women. While the rate at which females were selected as dissident nominees or Board Appointees in contested situations increased over the course of the study, it trailed the rising tide of female board representation in the broader S&P 1500 universe*.* There were zero female Dissident Directors in 2011, two in 2012, and three in 2013. Similarly, there were two female Board Appointees in 2011, but zero in both 2012 and 2013.

Activism does not promote racial/ethnic diversity. Less than five percent of Study Directors were ethnically or racially diverse. While minority representation across the entire S&P 1500 board universe slowly increased over the course of the study, from 9.3 percent in 2011 to 10.1 percent in 2015, the rate at which individuals with diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds were selected as Dissident Directors and Board Appointees was relatively uniform and trailed that of the broader index by more than five percentage points.

Activism boosts boardroom independence. Study Directors were generally more independent than their counterparts across the broader S&P 1500. Not surprisingly, dissident nominees and directors appointed to boards via settlements were more likely to be “independent” than directors appointed unilaterally by boards in connection with shareholder activism. It is worth pointing out that the measure of “independence” focused on a nominee’s degree of separation from management rather than from the dissident. Indeed, as the examination of prior boardroom experience suggests, there may be questions of independence from activist sponsors for a subset of Study Directors.

Prior boardroom experience is not required. Boardroom experience does not appear to be a prerequisite for contest candidates. More than half of Study Directors held outside board seats. While most of these directors sat on either one or two outside boards, a sizable minority pushed the over-boarded envelope. Six Study Directors served on four outside boards, four on five outside boards, and one on six outside boards. Many of these “busy” directors appear to be “go-to” nominees for individual activists. The serial nomination of favorite candidates raises questions about the “independence” of these individuals from their activist sponsors.

Investment professionals and sitting executives dominate the candidate pool for contested elections. Occupational data for the Study Directors demonstrates experience, qualifications, attributes, and skills (EQAS) preferences for nominees in contested situations. “Corporate executives” and “financial services professionals” were in a dead heat at the front of the pack. These favored occupations were not evenly distributed, as activists tended to select investors and incumbents tended to select executives. In fact, Dissident Directors were nearly three times more likely to be “financial services professionals” than Board Appointees, while Board Appointees were nearly twice as likely to be “executives” than Dissident Directors.

Part II: Board Profile

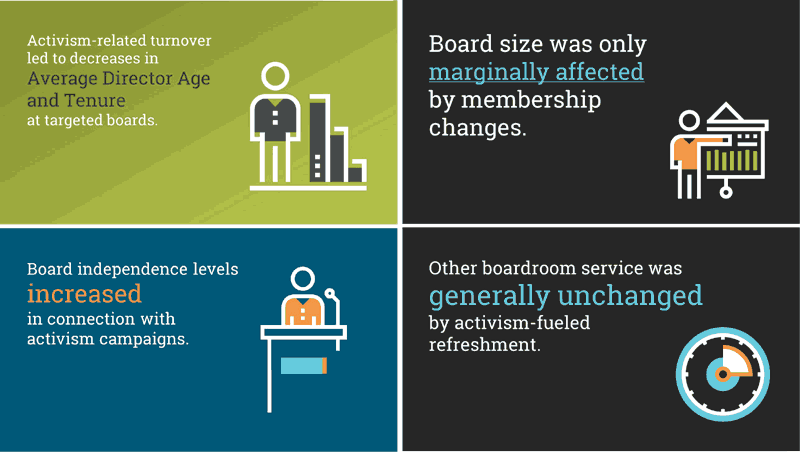

Snapshot: Public shareholder activism generally resulted in boards that are younger, shorter-tenured, slightly-larger, more independent, and more financially literate, but less diverse, than their pre-activism versions.

Activism-related turnover led to decreases in average director age and tenure at targeted boards. Dissident Directors averaged 53 years of age and Board Appointees averaged 56.3 years of age. Average director age decreased by 2.6 years to 59.6 years on Study Boards targeted by shareholder activists, while average director tenure decreased by 3.4 years to 6.1 years. For the broader S&P 1500 in 2015, average director age was 62.5 years and average tenure was 8.9 years.

Board size remained relatively steady despite membership changes. Although average board size at Study Companies increased from nine to 9.4 seats, less than half (41.9 percent) of the Study Companies experienced a post-activism boost in board size. 18.3 percent of Study Companies experienced a decline in board size following shareholder activism, while board size was unchanged at 39.8 percent of Study Companies.

Board independence levels increased in connection with activism campaigns. Average board independence at Study Companies increased from 79.5 percent to 83 percent. More than 60 percent of study companies experienced an increase in independence, 21.5 percent experienced a decrease, and 18.3 percent experienced no change. Average board independence in the S&P 1500 was 80.6 percent in 2015.

Other boardroom service was generally unchanged by activism-fueled refreshment. The average number of outside boards on which Study Company directors served remained virtually flat, increasing from 0.8 to 0.9. Of the 89 Study Companies, the number without a director who sat on more than one outside board decreased from four to two. There was a correlation between company size and outside board service, as directors at S&P 500 and S&P 400 study companies sat on a higher average number of outside boards than their counterparts at S&P 600 study companies.

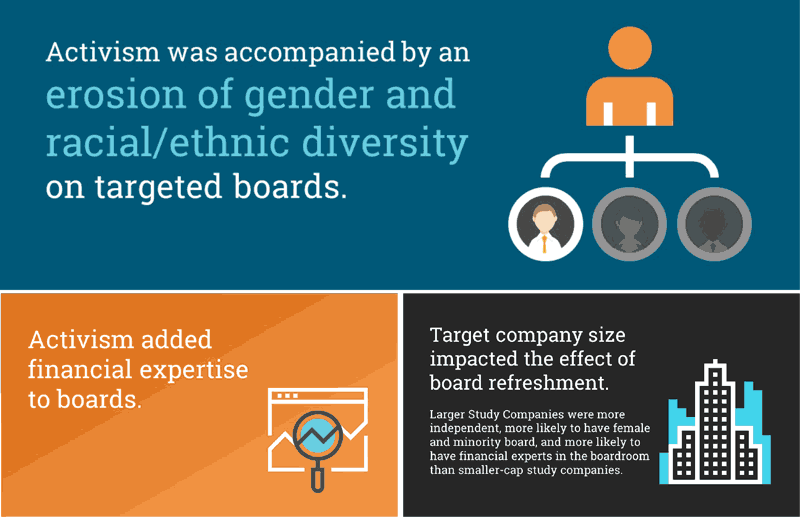

Activism was accompanied by an erosion of gender and racial/ethnic diversity on targeted boards. Study Company boards were less likely to have at least one female director following an activism campaign than they were preceding one, decreasing from 87.1 percent to 82.8 percent. Similarly, Study Company boards were less likely to have at least one minority director following an activism campaign than they were preceding one, decreasing from 55.9 percent to 51.6 percent. According to Board Refreshment Trends at S&P 1500 Firms, the proportion of S&P 1500 companies with at least one female director increased from 72 percent in 2011 to 82.7 percent in 2015 and the portion of S&P 1500 companies with at least one minority board member increased through the course of the study period to 56.8 percent.

Activism added financial expertise to boards. The proportion of board seats at Study Companies occupied by “financial experts” increased from 22.6 percent (189 of 835) to 24.5 percent (214 of 874). The number of Study Companies with at least one, two, or three “financial experts” also increased. (At U.S. companies, ISS considers a director to be a “financial expert” if the board discloses that the individual qualifies as an “Audit Committee Financial Expert” as defined by the Securities and Exchange Commission under Items 401(h)(2) and 401(h)(3) of Regulation S-K. Under the SEC’s rules, a person must have acquired their financial expertise through (1) education and experience as a principal financial officer (PFO), principal accounting officer (PAO), controller, public accountant or auditor or experience in one or more positions that involve the performance of similar functions, (2) experience actively supervising a PFO, a PAO, controller, public accountant, auditor or person performing similar functions; (3) experience overseeing or assessing the performance of companies or public accountants with respect to the preparation, auditing or evaluation of financial statements or (4) other relevant experience.)

Target company size impacted the effect of board refreshment. Larger Study Companies were more independent, more likely to have female and minority board members (both pre- and post- activism), and more likely to have financial experts in the boardroom than smaller-cap study companies. Relative to their larger peers, smaller Study Companies generally experienced more pronounced declines in average director age and tenure, but experienced more significant increases in average board size.

The complete publication is available here.

Print

Print