Subodh Mishra is Executive Director at Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. This post is based on an ISS Governance Insights article by Etelvina Martinez, Associate Vice President, ISS Corporate Solutions, a unit of Institutional Shareholder Services.

Four years ago, the Target data breach brought a spotlight on a “new” type of risk: cybersecurity. Of course, the risk wasn’t really new, but the scale of the breach, and the size of the public reaction, was the tipping point for many boards to recognize that they needed to manage cybersecurity risk at the board level. After all, the magnitude of the financial impact was certainly board-level; reports indicate that the 2013 data breach cost Target (and ultimately their shareholders) more than $100 million (after insurance recoupments and tax impacts).

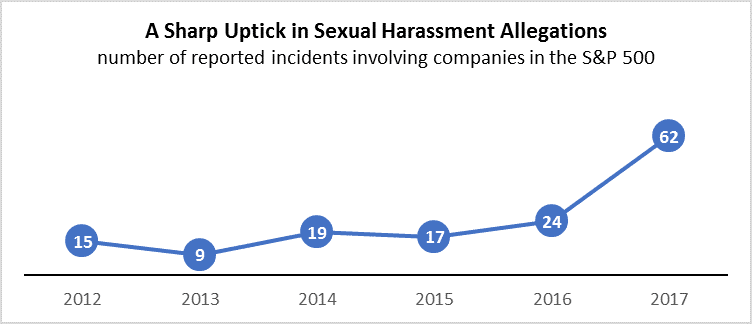

Today, many boards find themselves in the same position yet again. High-profile sexual misconduct cases in the corporate setting are surfacing at a rapid pace, and many companies have not put effective sexual misconduct risk oversight mechanisms in place—particularly at the board level. And again, it’s not a “new” risk—rather, it’s a risk that, based on societal shifts, has now reached its own tipping point. With the growing tide of sexual harassment cases, boards of directors are challenged to broaden their notion of risk and redefine their roles in managing it.

Source: ISS-Ethix

And, like cybersecurity, sexual misconduct can have a dramatic financial impact on investors. The recent disclosure case at Wynn Resorts saw close to $3 billion in market capitalization wiped out in a matter of days. But the impacts of sexual misconduct can hide far deeper within the organization, in places that are not so easily measured. These relate to what abusive and discriminatory workplace environments do to erode employee morale, reduce productivity, and increase recruitment and retention costs, to name but a few.

A cultural problem requiring top-level oversight

Sexual harassment and discrimination are fundamentally issues of culture. An organization can have a robust set of policies and procedures in place, but if it does not embrace the value of gender equality, and does not embed it deeply within its culture, it won’t be successful in combating the problem. Thus, diversity and equality need to be priorities at the highest levels of an organization, starting with the board of directors.

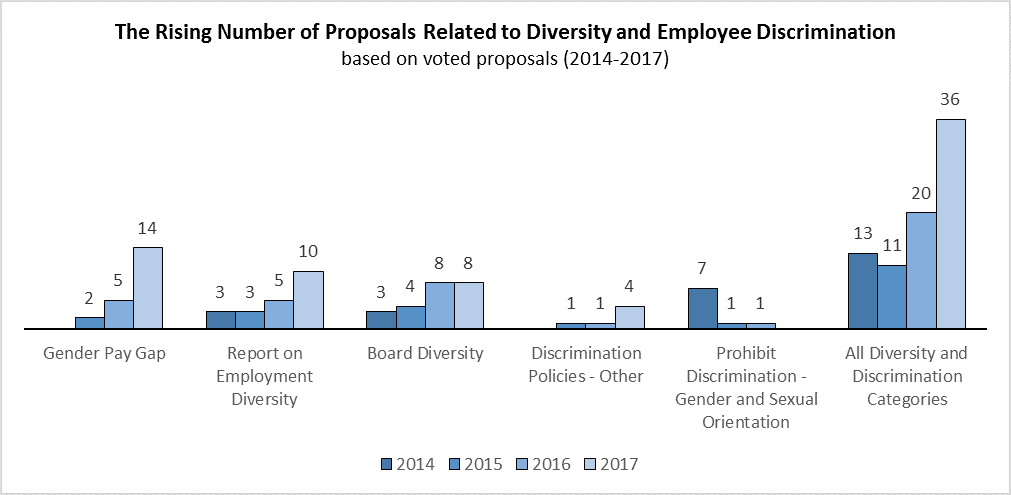

Many investors understand these risks, and have begun to pay closer attention to workplace diversity and gender equity. However, with limited visibility into the inner workings of a corporation’s culture and few externally available metrics, it can be hard to tell the good actors from the bad. Investors typically focus on the few markers available that give a sense of a corporations’ approach to workforce equality, such as the degree of gender diversity at the board and C-suite levels. At the same time, some investors seek greater transparency through direct engagement or by submitting shareholder proposals on an array of gender-related issues like gender pay parity and board diversity.

Source: ISS Voting Analytics

Five signs of effective sexual misconduct risk management

In light of the significant risks involved, the following are some proactive measures boards can take to help formalize their role in overseeing this risk and to signal to investors—and employees—that the board is committed to ensuring a safe workplace.

1. Sexual misconduct risk is specifically enumerated and oversight assigned to a board committee. Making the oversight of anti-harassment and discrimination policies and procedures the mandate of a board sub-committee compels more detailed and focused attention on the matter. Some signs that the board is managing the risk include:

- Regularly reviewing policies and procedures to confirm that effective grievance mechanisms are in place. These policies should not rely solely on reporting by victims, but they should also urge bystanders to come forward.

- Requiring regular reports of complaints and outcomes. In cases involving senior management, complaints should be channeled directly to the committee.

- Proactively performing regular corporate culture health checks. Having access to individuals at various levels of the organization facilitates getting a less filtered read on culture. Through these checks, it is critical to assess general employee awareness of policies and procedures, and whether employees feel safe reporting incidents or fear retaliation. Moreover, these systems should give boards insight into how women and minority employees are perceived within the organization through monitoring of retention and advancement rates for these employees.

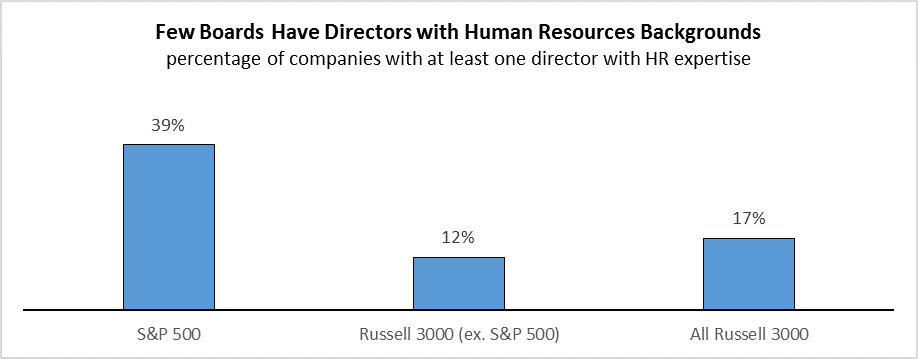

2. The board has expertise in workplace and employee issues. It is uncommon to find directors with deep human resources-related backgrounds on boards. However, dealing with workplace topics such as inclusion and safety are integral parts of HR professionals’ roles. Boards would benefit from this type of background to better understand the nature of the problem and potential solutions.

Source: ISS DataDesk

3. Material penalties are in place for perpetrators and abettors. Imposing real penalties for abusive behavior sends a clear message of non-tolerance. Companies may include a trigger within compensation clawback policies for misconduct relating to sexual harassment or discrimination. Termination of employment for cause may serve as the ultimate corporate penalty for offenders. These policies may also be extended to any individuals that willfully concealed violations or engaged in retaliation against whistleblowers.

4. Executive compensation structures—at a minimum—contain incentives for creating a safe and equitable workplace. Promoting a diverse and equitable workplace culture helps to create an environment where employees feel valued and safe and where an abusive culture is less likely to take hold. Integrating diversity into the organization’s goals and compensation structure will help maintain focus on the objective and offer a means of tracking progress. Currently, a small fraction of companies focus on diversity as part of their incentive schemes. As of January 2018, only 28 U.S. companies included the improvement of culture or diversity in their performance goals for CEOs, based on our review of ISS Incentive Lab data of short term incentive metrics for more than 2,300 U.S. firms.

5. The company models the behavior it seeks to promote. The board’s makeup should reflect the company’s values by including a diverse group of directors. It is difficult to give credence to claims of being an inclusive organization if there is a lack of women and minority directors on the board. And at many organizations, this same principle extends down into the C-suite and even to the layer of management below; ensuring that there is a diverse group of leaders managing the company day-to-day also may help mitigate the risk.

Sexual harassment is hardly a new problem, but the current moment of intense scrutiny serves as an opportunity to make significant progress in facing the issue head-on. The risks of not addressing the problem are too high for companies, and investors expect that boards of directors will play a leadership role.

Print

Print