Jamie Allen is Secretary General and Li Rui (Nana Li) is Senior Research Analyst at the Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA). This post is based on the introduction to their ACGA report.

With its securities market continuing to internationalise and grow in complexity, China appears at a turning point in its application of CG and ESG principles. The time is right to strengthen communication and understanding between domestic and foreign market participants.

Introduction: Bridging the gap

The story of modern corporate governance in China is closely connected to the rapid evolution of its capital markets following the opening to the outside world in 1978. The 1980s brought the first issuance of shares by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and a lively over-the-counter market. National stock markets were relaunched in Shanghai and Shenzhen in 1990 to 1991, while new guidance on the corporatisation and listing of SOEs was issued in 1992. The first overseas listing of a state enterprise came in October 1992 in New York, followed by the first SOE listing in Hong Kong in 1993. Corporate governance reform gained momentum in the late 1990s, but it was less a byproduct of the Asian Financial Crisis than a need to strengthen the governance of SOEs listing abroad. The early 2000s then brought a series of major reforms on independent directors, quarterly reporting and board governance aimed squarely at domestically listed firms.

A great deal has changed in China since then, with periods of intense policy focus on corporate governance followed by consolidation. In recent years, China’s equity market has undergone a renewed burst of internationalisation through Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Connect, relaxed rules for Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors, and the landmark inclusion of 234 leading A shares in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index in June 2018. While capital controls and other restrictions on foreign investment remain, there seems little reason to doubt that foreign portfolio investment will play an increasing role in China’s public and private securities markets in the foreseeable future.

Running parallel to market internationalisation, and facilitated by it, is a broadening of the scope of corporate governance to include a focus on environmental and social factors (“ESG”), and a deepening concern about climate change and environmental sustainability. Pension funds and investment managers in China are now encouraged by the government to look closely at ESG risks and opportunities in their investment process. And green finance has become big business in China, with green bond issuance growing steadily. Indeed, these themes are also part of the newly revised Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies (2018) from the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC); this is the first revision of the Code since 2002.

Turning point

China thus appears at a new turning point in its market development and application of corporate governance principles. While it is difficult to predict how this process will unfurl, we believe three broad developments would be beneficial:

- That unlisted and listed companies in China see corporate governance and ESG not merely as a compliance requirement, but as tools for enhancing organisational effectiveness and corporate performance over the longer term. This applies as much to entrepreneurial privately owned enterprises (POEs) as established SOEs. The view that good governance is not relevant or possible in young, innovative firms is misguided.

- That domestic institutional investors in China see corporate governance and ESG not only as tools for mitigating investment risk, but as a platform for enhancing the value of existing investments through active dialogue with investee companies. The process of engagement can also help investors differentiate between companies that take governance seriously and those which do not.

- That foreign institutional investors view corporate governance in China as something more nuanced than a division between “shareholder unfriendly” SOEs and “exciting but risky” POEs. We recommend foreign asset owners and managers spend more time on the ground in China and invest in studying China’s corporate governance system, if they are not already doing so.

Of course, there are many exceptions to these broad characterisations. It is possible to find companies which view governance as a learning journey—and they are not necessarily listed. Certain mainland asset managers have begun investigating how to integrate governance and ESG factors into their investment process. And there are a growing number of foreign investors, both boutique and mainstream, that have developed a deep understanding of the diversity among SOEs and POEs and which have achieved excellent investment returns from SOEs as well.

Not surprisingly, however, our research has found that significant gaps in communication and understanding do exist between foreign institutional investors and China listed companies. According to an original survey undertaken by ACGA for this report, a majority of foreign investor respondents (59%) admitted that they did not understand corporate governance in China. Only 10% answered in the affirmative, while another 31% felt they “somewhat” understood the system. Conversely, it appears that most China listed companies do not appreciate the challenges that foreign institutional investors face in navigating “corporate governance with Chinese characteristics”.

This report is written for both a domestic and international audience. Our aim is to describe in as fair and factual a manner as possible the system of corporate governance in China, highlighting what is unique, what looks the same but is different, and areas of genuine similarity with other major securities markets. The main part of the report focuses on “Chinese characteristics” and looks at the role of Party organisations/committees, the board of directors, supervisory boards, independent directors, SOEs vs POEs, and audit committees/auditing. Each chapter explains the current legal and regulatory basis for the governance institution described, the particular challenges that companies and investors face, and concludes with suggestions for next steps. Our intention has been to craft recommendations that are practical and anchored firmly in the current CG system in China—in other words, that are implementable by companies and institutional investors. We hope the suggestions, and indeed this report, will be viewed as a constructive contribution to the development of China’s capital market.

The remainder of this Introduction provides an overview of key macro results from our two surveys. We start with the good news—that a large proportion of foreign institutional investors and local companies are optimistic about China—then highlight the challenges both sides face in addressing governance issues. The following chapters draw upon additional material from the two surveys.

ACGA survey—The big picture

Are you optimistic?

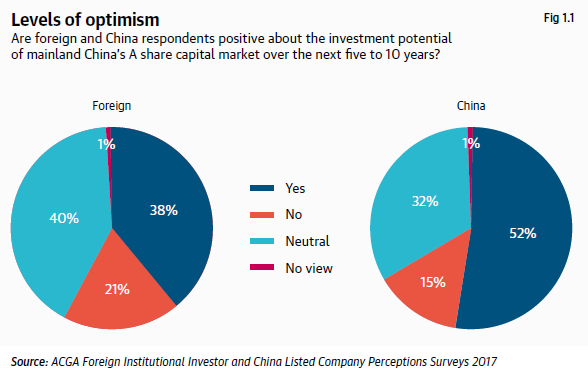

The good news from our survey is that a sizeable proportion of both foreign investors (38% of respondents) and China listed companies (52%) are optimistic about the investment potential of the A share market over the next five to 10 years, as Figure 1.1 below shows. Only 21% of foreign investors are negative, while the remainder are neutral. Not surprisingly, only 15% of China respondents were negative, while almost one-third were neutral.

Do you agree with MSCI?

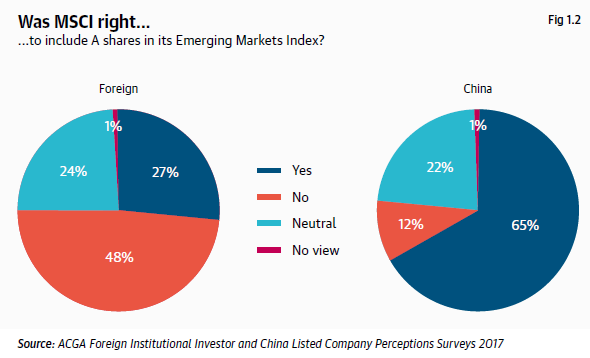

The picture diverges on the issue of whether MSCI was right to include A shares in its Emerging Markets Index in 2018: only 27% of foreign respondents agreed compared to 65% of Chinese respondents, as Figure 1.2, below, shows. Almost half the foreign respondents did not agree compared to a mere 12% for Chinese respondents. A similar proportion was neutral in both surveys.

Challenges—Foreign institutional investors

The investment process

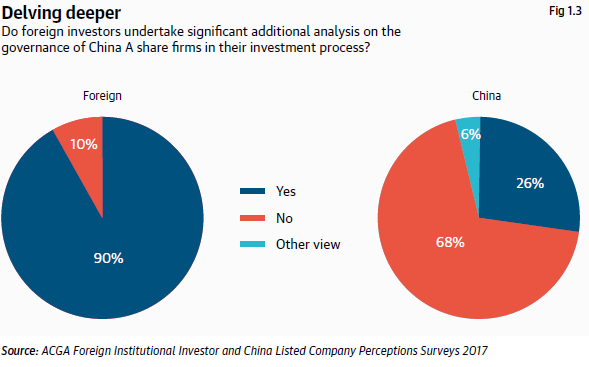

Foreign investors face a range of challenges investing in China, the first of which is understanding the companies in which they invest. As Figure 1.3 below indicates, foreign investors do not rely solely on information provided by companies when making investment decisions, but utilise a range of additional sources. It appears that listed companies are not aware of this issue.

Company engagement

Company engagement

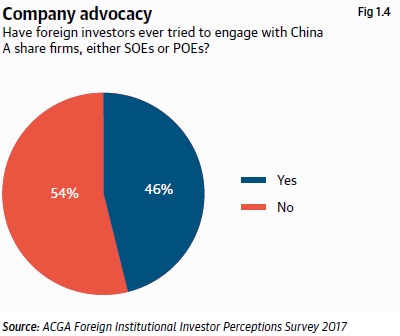

Globally, institutional investors seek to enter into dialogue with their investee companies. It is no different in China, as shown in Figure 1.4.

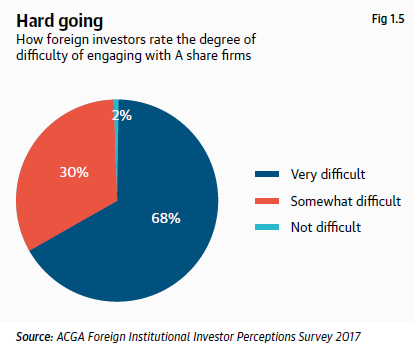

But the process is not easy.

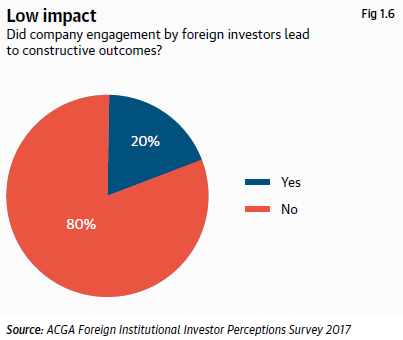

And successful outcomes are fairly thin on the ground to date.

Common threads

Respondents gave a range of answers as to why the process of engagement was difficult and successful outcomes limited, but some common threads were discernible:

- Language and communication: In addition to straightforward linguistic difficulties (ie, companies not speaking English, investors not speaking Chinese), the communication problem is sometimes cultural. As one person said, “Even though I am from China, it is hard to interpret hidden messages.”

- Access: Getting access to companies can be difficult. Getting to meet the right senior-level person, such as a director or executive, can be even more challenging.

- Investor relations (IR): While some IR teams are professional, many are not. As one respondent commented: “IR (managers) are not very well trained and some of them lack basic understanding or knowledge of corporate governance or even financial information.”

- CG as compliance: A common complaint is that companies view CG as merely a compliance exercise. Some refuse to give “detailed answers beyond the party line”.

- Non-alignment: There is a recurring feeling that the interests of controlling shareholders in SOEs are not aligned with minority shareholders. One investor commented on the “lack of responsiveness” to outside shareholder suggestions, adding that SOEs “wait for government to give the direction, not investors”.

- Lack of understanding: There can be a significant gap in the awareness of CG and ESG principles.

Empathy for companies

Conversely, a few respondents expressed empathy for the position of companies. As one wrote: “There also appears to be an under appreciation by international investors of the differences in culture, political context, and the path and stage of economic development between China and the rest of the world. Any attempt at influencing changes without a reasonable understanding of these differences is likely to be ineffective and (may) at times lead to unintended consequences.”

Another explained some of the regulatory challenges facing listed companies: “With a few exceptions, both SOEs and POEs have to deal with stringent and ever-changing industry regulations and government policies.”

A third said that some engagement had been positive: “Generally, where I have had access to the right people, engagement has been constructive. I suspect this is a result of the companies already appreciating the value of good governance in attracting non-domestic investors.”

And perhaps the most positive comment of all: “A number of the Chinese companies we speak to, especially the industry leaders, already address ESG risks in their businesses. Most of them publish ESG reports annually, which help to set the benchmark for their industry and also to garner positive feedback from society and hence, end-customers. Some of such companies end up enjoying a pricing premium on their products once this positive brand equity has been established. This creates a virtuous cycle, where ESG becomes part of their corporate culture. They understand that for the long-term sustainability of their business, and for the benefits of all their stakeholders, such investment can only enhance their competitiveness.”

Brave new world of stewardship

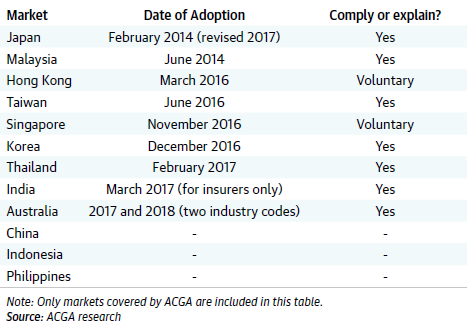

Yet most investors still find engaging with companies a challenge. A further reason may be that China is one of only three major markets in Asia-Pacific that has not yet issued an “investor stewardship code”. Such codes push institutional investors to take CG and ESG more seriously, incorporate these concepts into their investment process, and help to encourage greater dialogue between listed companies and their shareholders (see Table 1.1, below). In recent years, the bar has been quickly raised on this issue in Asia and expectations have risen commensurately.

Without an explicit policy driving investor stewardship, it is unlikely that the average listed company will give proper weight to a dialogue with shareholders. As one foreign investor said: “Generally speaking, it is relatively easier to engage with bigger listed companies. SOEs and larger companies tend to be more responsive. SOEs have more incentive to do so following government guidelines and trends.”

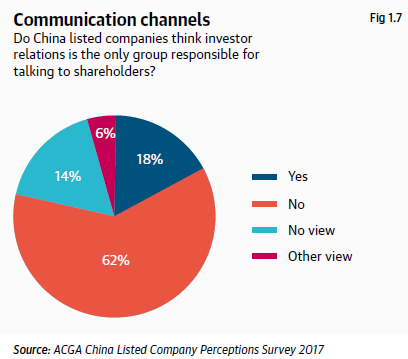

A key question to ask is who within a company should be responsible for engaging with shareholders? The short answer is the board, as a group representing and accountable to shareholders. Indeed, on a positive note, our survey found that most Chinese listed companies do admit that the responsibility for talking to shareholders should not be placed solely on the investor relations (IR) team (see Figure 1.7 below). But given that delegating this task to IR remains a common practice, it would appear that there is an inconsistency between words and actions here.

Challenges—China listed companies

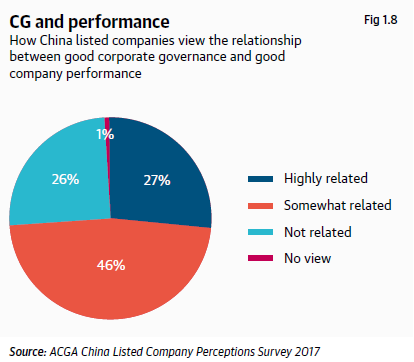

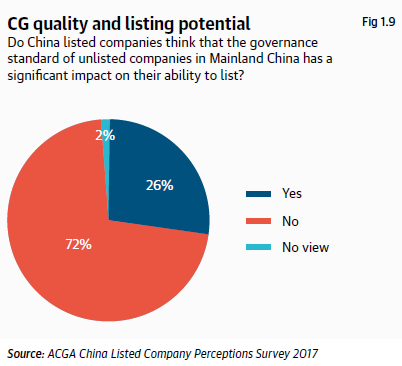

Some additional factors clearly play on the willingness of companies to take CG and ESG seriously, as Figures 1.8 and 1.9 below show.

Does the market reward good CG?

Only 27% of the respondents to our China listed company survey believe there is a close correlation between good corporate governance and company performance. Another 46% think they are “somewhat related”, while a quarter see no relationship. These results broadly align with the view common in most markets, including China, that only a minority of companies (usually the large caps) feel incentivised to improve their governance practices and that they will be rewarded by investors if they do so.

Even more concerning is the largely negative view on whether better governance helps a company to list.

As an aside, this might also help to explain why listed POEs in China are generally not seen as being a better investment proposition or as having better governance than SOEs—an issue we explore in Chapter 3.5.

Only 23% of foreign respondents said they preferred investing in POEs over SOEs, while two-thirds said they did not. Meanwhile, only 10% of China listed companies thought POEs were better governed than SOEs. Around one-third thought they were about the same, while 54% thought POEs were worse.

Even so, in a fast-growing market such as China, there is a risk in taking a static or one-dimensional view.

‘Companies will have to become more ESG aware’

We conclude this section with a wide-ranging comment from a China-based institutional investor on the need to see governance and ESG as a process:

- Chinese companies are generally financial weaker than their more established peers in developed markets. This is a symptom of markets being at different stages of development. For Chinese companies, survival is the top priority. Once they have gained enough market share and accumulated a certain level of capital reserves, they will start to consider ESG issues. This will help them cement their market position and grow more healthily in the long term.

- At the moment, we recognise that the cost of not practicing ESG is not high in China. But things are changing, especially on the environmental front. We can see that the government is very serious about closing down small players who are not compliant with emission standards. The quality of air, earth and water concerns the livelihood of every citizen, and we believe that there will be heightened enforcement of pollution laws.

- Corporate governance is also improving as public shareholders get more actively involved in major corporate actions. Having said that, shareholder structures remain highly concentrated, especially for SOEs in China, and external forces may not be strong enough to ensure a proper division of power.

- We see increasing numbers of entrepreneurs and companies more willing to give back to society and the challenge here is simply that philanthropy is quite new in China.

- As society becomes more civilised and consumers become more aware of issues such as child labour and environmental pollution, Chinese companies will have to become more ESG aware and responsible.

Interview: ‘Character and quality of management is critical’

David Smith CFA, Head of Corporate Governance, Aberdeen Standard Investments Asia, Singapore

What is your view on investing in A shares?

We have an A share fund, so naturally, we have spent substantial time and effort getting comfortable with both the market and the companies. There are well-documented risks surrounding investing in China, but the market has obvious attractions China is leading the world in some of the sectors, like e-commerce, for example. As investors, we always have to balance return with macroeconomic risk, political risk, regulatory risk, and so on, and this is certainly the case for China.

What is your view on stock suspensions in China?

The situation is getting better but companies too often still choose to suspend given a pending “restructuring”, which protects potential investors at the expense of existing investors, something that can be incredibly frustrating given how long we can be locked up for. There is a general misunderstanding in China as to what suspension means: companies should only suspend when there is information asymmetry, not when there is uncertainty. We are paid to analyse and deal with uncertainty, and the market will find a price for it. If companies have to suspend whenever there is uncertainty, we won’t have a stock market in place.

In general, there are too many suspensions in China. If a company has a restructuring plan or a regulatory investigation is going on, it should just disclose this through an announcement; as long as everyone in the market knows the same information, the stock should keep trading.

The issue of price-sensitive information has already been taken care of by regulations around continuous disclosure, so a suspension is often not protecting anyone, it just removes liquidity for existing investors. This issue is exacerbated by the bizarre and unusual situation of dual-listed A/H share companies suspending on one exchange and not the other.

In developed markets, in contrast, suspensions of issuers lasting more than a month for whatever reason are very rare. Part of the issue is also that promoter shares might sometimes have been pledged, so promoters want to avoid a share price fall triggering a margin call.

What are the top CG issues you have observed in Chinese companies?

Entrepreneur risk (people risk) is the most obvious one, including related-party transaction risks, along with operational and execution risks. For Aberdeen, we never invest if we feel uncomfortable with the founder or management. Both the character and quality of the people inside the company is something we value a lot in our investment decision-making process.

Regulatory risk is another issue. Changes in regulations can affect not just SOEs but also POEs to different extents. For example, the recent regulatory change on the reinforcement of Party committees inside Chinese companies is not what foreign investors expected to see as the direction of corporate governance development in China.

Another issue is that given more and more onus put on independent directors, maybe we need to think about another way to elect them. The current situation involves voting for independent directors on their independence, rather than competence. However, “independence” can be easily gamed in Asia. Many independent directors are structurally independent but rely on the company for their living (pension), so investors are increasingly asking if/how they add value to board discussions.

What is your view on voting trends among China listed firms? Does voting lead to engagement

Not much has changed. Any voting against has tended to focus on resolutions like related-party transactions, or other corporate actions, rather than issues across the board.

Engagement is getting a little bit better in China. We have seen more and more companies listening to us, and dialogue is getting much better. Companies increasingly understand that we are not in China for the short-term and that our interests are aligned. That certainly helps.

Methodology

A tale of two surveys

The two surveys in this report, the “ACGA Foreign Institutional Investor Perceptions Survey 2017” and the “ACGA China Listed Company Perceptions Survey 2017”, were developed internally in the first half of 2017 and carried out over 21 July to 1 September of that year. They were distributed through ACGA’s global network of members and contacts, and by a number of supporting organisations both inside and outside China (see the Acknowledgements page for details).

Purpose

We decided to conduct a survey at the preliminary stage of this project for two main reasons. The first was to add a broader range of perspectives to the report and to complement the extensive research carried out by ACGA and our contributing authors.

The second was to develop new data on corporate governance in China. When we began researching this report, we found that much of the information on board structures and governance practices in China was out of date, incomplete or non-existent. We developed the survey to partially fill this gap. To complement this information, we turned to data providers such as Wind and Valueonline to provide raw data on which we could do original analysis—and we carried out our own reviews of specific governance practices among large listed companies.

Foreign Institutional Investor Perceptions Survey

The Foreign Institutional Investor Perceptions Survey contained 22 questions and focused on areas that we believe are relevant to China’s investment potential and governance. They can be divided into the following categories:

- Macro questions, such as capital market development, MSCI inclusion, SOEs vs POEs, and mainland-listed vs overseas-listed firms.

- Shareholder rights, including investor protection in China vs overseas.

- Company governance, including corporate reporting, role of chairman, independent directors, supervisory boards.

- Role of government, including appointment of chairmen, intervention in SOEs and POEs, the role of the Party organisation/committee.

- Investor engagement with companies.

Several of the questions provided options for respondents to give detailed answers and, where relevant, these comments are incorporated into our text.

The survey was developed by ACGA in Q2 2017 and first tested with a select group of ACGA global investor members in June of that year. It was refined based on feedback received before being sent out electronically in July. The recipients were primarily drawn from among ACGA’s list of institutional investor members based in Asia and around the world. This was complemented by recipients from our supporting organisation membership networks.

In total, we received 155 complete and comparable responses. Partial responses were not counted. Based on information gathered about respondents’ titles, they fell into three broad groups: CEOs, directors, managing directors or partners; portfolio managers and analysts; and managers or specialists in CG, ESG or stewardship. A large proportion held senior roles in their organisations.

The total assets under management (AUM) of all respondents amounted to around US$40 trillion, with the range from US$20m to US$6 trillion. In other words, a mix of both boutique investment managers and large mainstream institutions.

China Listed Company Perceptions Survey

The China Listed Company Perceptions Survey contained 12 questions and likewise focused on areas that we believe are relevant to such companies, their directors and managers. While there were fewer questions in this survey, they covered similar categories as in our foreign survey, namely macro issues, company governance, role of government, and investor engagement.

We designed some questions to be identical to the Foreign Institutional Investor Survey, in order to allow direct comparisons between corporate and investor perspectives on the same issue.

We also asked some unique questions of companies, such as whether or not they see a close correlation between corporate governance and performance, and whether better governance helps a firm list its shares.

The survey recipients were drawn from among ACGA’s corporate membership base, as well as clients and contacts of supporting organisations.

In total, we received 182 complete responses from which we extracted the survey results. Most respondents held senior positions in their companies such as directors, executives, board secretaries and senior managers. Most of the companies represented have been listed in China for more than five years and have a market cap of more than Rmb5 billion (US$800m approx). Further demographic data on the two groups of respondents follows:

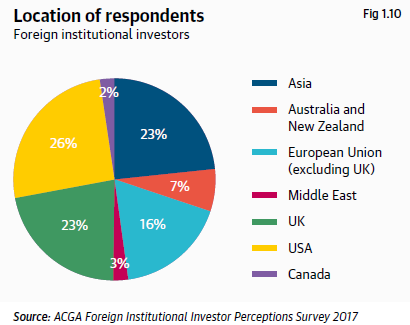

Foreign respondents

The foreign institutional investors who responded are mostly from the US, UK, Asia and the European Union, as shown in Figure 1.10 below. The response is consistent with the distribution of ACGA members by region. Investors from Australia, New Zealand, the Middle East and Canada also responded to the survey.

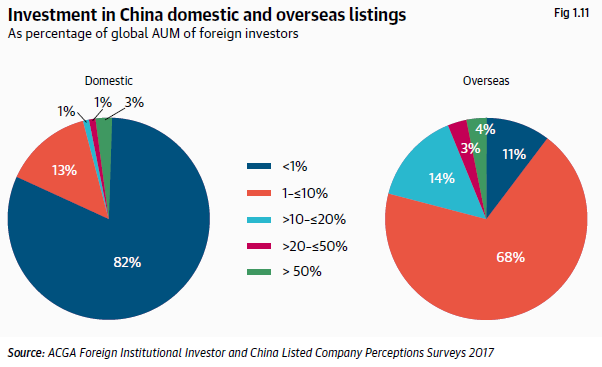

In terms of their global AUM, the vast majority of respondents have less than 1% invested in China A shares, while a significant minority have between 1% and 10%. Very few have more than 10% of their funds invested in China domestic listings, although interestingly a few have more than 50%. The latter would be smaller investment managers with a dedicated China focus, as shown in Figure 1.11.

The picture changes markedly when overseas-listed Chinese firms are taken into account: the majority of foreign respondents allocate between 1% to 10% of their global AUM to such companies and a sizeable proportion, about one-fifth, invest more than 10%.

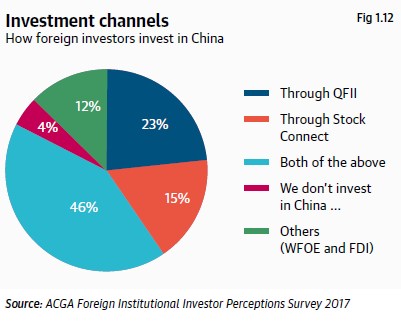

How do foreign investors invest in China? As Figure 1.12 below shows, around a quarter go only through the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) scheme, 15% only through Stock Connect, and almost half through both channels. Interestingly, a significant minority invest directly through wholly owned foreign enterprises (WFOEs) or other foreign direct investment (FDI) channels.

China respondents

Most respondents to our China Listed Company Perceptions Survey work for a company that has been listed for more than five years. Around 40% of the companies have been listed for more than 10 years, which is a relatively long period given that the Chinese stock market is still less than 30 years old (see Figure 1.13).

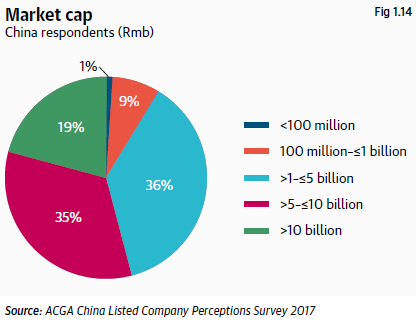

The market cap of 54% of respondents’ companies was more than Rmb5 billion, as highlighted in Figure 1.14, and 19% have a market cap of more than Rmb10 billion. Generally, the larger firms are likely to be SOEs.

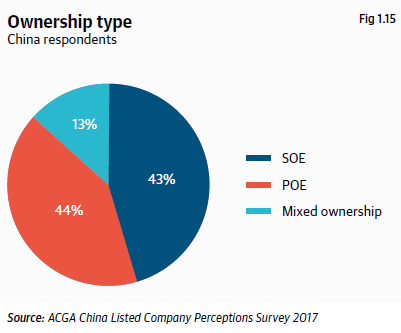

In terms of ownership, the distribution of respondents falls evenly between SOEs and POEs, with 13% being of a “mixed-ownership” type (see Figure 1.15, above). This gives us confidence that the survey results incorporate a range of views from different participants in the Chinese market.

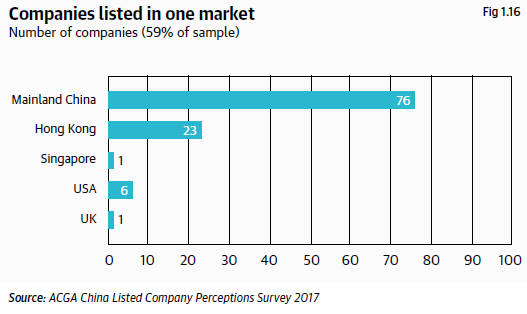

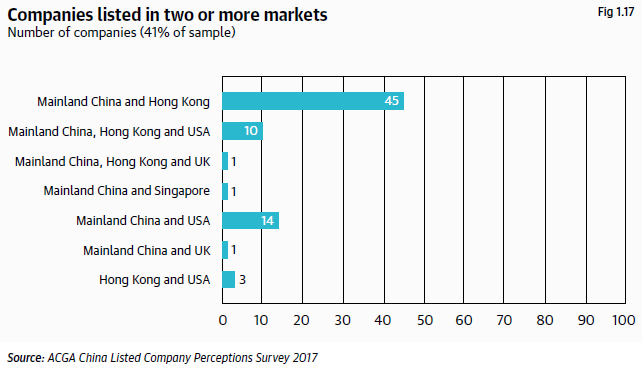

As for where respondents’ companies are listed, Figures 1.16 and 1.17, below, highlight that almost 60% are listed in a single jurisdiction. Mainland China comes first, not surprisingly, followed by a reasonable number in Hong Kong. Only a few respondents work for Chinese companies listed in Singapore, the US and the UK. Regarding the remaining companies listed in more than one jurisdiction, again the most popular venue is a dual-listing in China and Hong Kong, followed by a listing in China and the US. Some companies have a listing in China, Hong Kong and the US.

* * *

The complete report, in both English and Chinese, is available here.

Print

Print