Lucas Davis is the Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor in Business and Technology at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley; and Catherine H. Hausman is an Assistant Professor at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. This post is based on a VoxEU column and is related to their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Executive Compensation as an Agency Problem and the book Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation, both by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried.

Fortunes are made and lost every year as oil prices rise and fall, impacting the macroeconomy, the stock market, investment, and of course the value of oil and gas firms (Hamilton, 2009; Kilian and Park 2009; Baumeister and Kilian, 2016). What happens to the fortunes of the leaders of those oil and gas firms? In this post, we argue that the compensation of U.S. oil and gas executives is closely tied to oil prices—much more closely than economic theory would predict. Theory says that executives should be rewarded for the value they bring to a firm, and that they should be incentivized to take the best actions on behalf of the firm. With billions of dollars at stake each year, we argue that boards and shareholders may want to revisit how compensation is structured at these firms.

Executive compensation frequently comes under scrutiny, with shareholders as well as the general public asking questions such as whether executives are over-compensated (e.g., Costello 2011). This scrutiny at times zeroes in on oil and gas firms (Fowler and Lublin, 2013)—most recently related to questions about conflicts of interest at boards of directors (Casselman, 2009), other corporate governance concerns (Denning, 2018), and even climate change (Kent, 2018).

How Should An Exec Be Paid?

It’s helpful to step back and remember what executives do, and why they might be justified in receiving quite high compensation. CEOs and other executives make important strategic decisions. Oil and gas executives, for example, make critical decisions about where, when, and how much to invest in exploration and production. These decisions have long-lasting impacts on firm profitability. And so companies understandably want to be able to attract and retain the best executive talent possible.

In this context, how should executives be compensated? Hiring an executive is one example of a “principal-agent problem”—a board of directors (i.e., the “principal) hires an executive (the “agent”) to act on the behalf of the firm. The principal wants to reward the agent for working hard and making good decisions. So, compensation is tied to performance in some way, for instance, with stock options or with cash bonuses that are tied to the market value of the firm.

Nobel Prize winning economist Bengt Holmstrom pointed out that executives needn’t be rewarded (or punished) for lucky (or unlucky) breaks that impact firm performance (Holmstrom, 1979). In fact, by tying compensation to what other scholars have since called “observable luck,” the board is simply increasing the volatility of the executive’s compensation. To correct for this, a risk-averse executive would need a higher average level of compensation. Holmstrom and others have argued that it is easy to remove luck from compensation by, for example, basing compensation on a company’s performance relative to its competitors (Holmstrom and Milgrom, 1987).

Pay-for-Luck

In recent research (Davis and Hausman, 2018), we look at how compensation is structured in oil and gas firms, in light of the theory outlined above. We focus on 80 publicly-traded U.S. exploration and production companies, with a combined market value of almost half a trillion dollars. We exclude companies engaged partially or exclusively in oil refining, because the impact of oil prices for those companies is less clear (Borenstein and Kellogg, 2014).

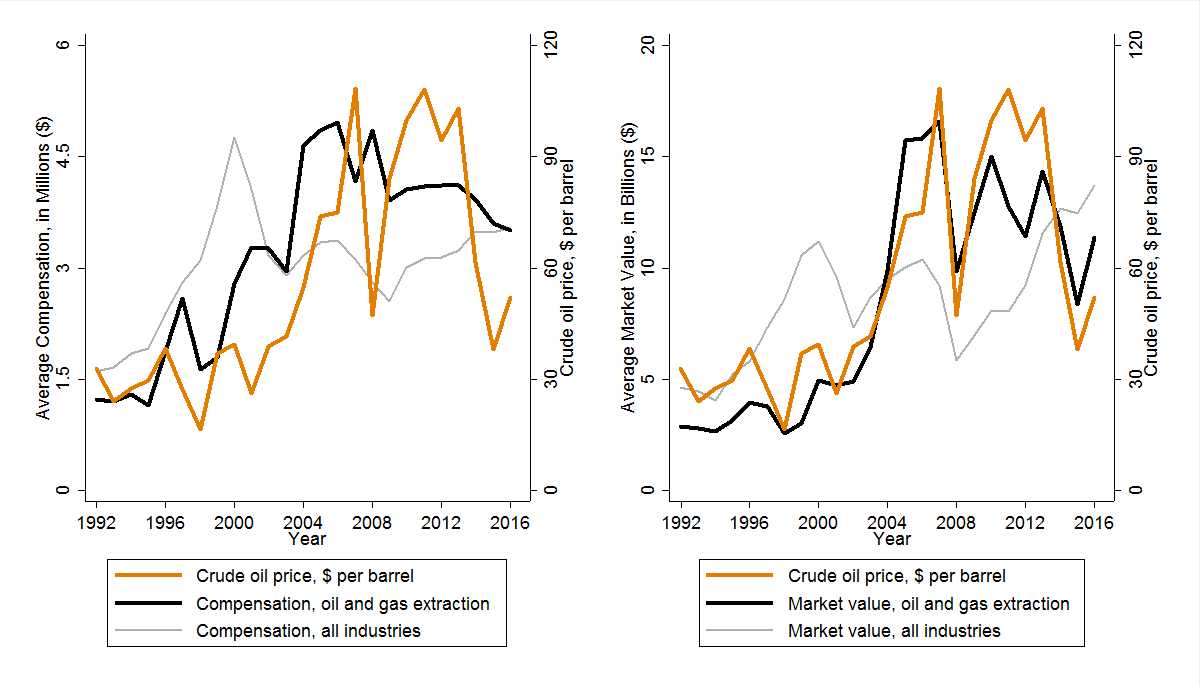

Crude oil prices are incredibly important for oil and gas firms—yet executives have no control over them. We show that a 10 percent rise in oil prices increases the market value of U.S. oil and gas production companies by 9.9 percent—almost a 1-for-1 relationship (see Figure 1). Perhaps in no other industry are so many companies’ fortunes driven by a single global price.

Figure: Energy Company Executive Compensation, Market Value, and Oil Prices

More surprisingly, we find that executive compensation follows a similar pattern. We find that a 10 percent rise in oil prices increases executive compensation by 2 percent. Moreover, compensation is nearly as sensitive to oil price changes as to generic changes in market value.

We are not the first to point out this relationship for oil and gas firms. An influential paper by Bertrand and Mullainathan (2001)—hereafter B&M—documented similar facts for an earlier period. It is striking to us that we continue to find this pay-for-luck relationship in oil and gas, because so many things have changed since the B&M analysis.

The U.S. oil and gas industry has undergone a major transformation, with the rise of new entrants and the shift to unconventional oil and gas plays. Equally importantly, executive compensation in general has changed in a number of important ways since the B&M analysis. Just after their paper, there was a dramatic increase in the use of stock options, followed by a partial reversal of that trend. Public scrutiny of executive compensation has increased, as has the stringency of regulatory rules regarding compensation at publicly-traded companies. Nonetheless, we continue to find pay-for-luck.

Returning to what CEOs do—a natural follow-up question is: can this simply be explained by oil and gas executives needing to exert more effort when oil prices are high? The answer is not necessarily obvious. For instance, perhaps a great executive is needed when times are bad, to weather the storm of low oil prices.

We tackled the question as follows. Supposing executive effort needs to scale 1-to-1 with other inputs (capital, labor), we can control for expenditures on these other inputs to see if that explains the changes in executive pay. But when we include controls for capital and labor in our regression, we still see an economically and statistically significant impact of oil prices on compensation—we still see pay-for-luck.

Interestingly, the most sensitive component of pay is cash bonuses and long-term incentives, implying that pay-for-luck cannot be explained by the use of stocks and options.

Related research has asked whether pay-for-luck can be explained by a “rent extraction story”—namely, whether executives are able to co-opt the pay-setting process (summaries are available in Bebchuk and Fried, 2003 and in Edmans and Gabaix, 2016). To explore this possibility, we considered a number of empirical tests.

Our primary empirical test is to separate companies by the number of insiders versus independents on the board of directors. We find that pay-for-luck is highest at the firms with insiders on the board, and lowest at the firms with independents on the board. These results suggest that when companies are less well-governed, it can be easier for executives to push through lucrative compensation packages.

We also look at a related test, following Garvey and Milbourn (2006) in testing for asymmetric effects. Indeed, we find that pay-for-luck is asymmetric, with executive compensation increasing more with rising oil prices than it decreases with falling oil prices. In the words of Garvey and Milbourn, this is consistent with the view that “important aspects of executive compensation are not chosen as part of an ex ante efficient contracting arrangement, but rather as a way to transfer wealth from shareholders to executives ex post” (p 224).

Implications

It is possible that our results are explained by companies simply failing to “filter out” oil price volatility. If so, one remedy might be relative performance evaluation. Alternatively, compensation contracts could explicitly filter out movements in oil prices, a la Holmstrom and Milgrom, 1987. We suspect that oil executives are at least somewhat risk-averse and might like insurance against this volatility.

It is also possible, however, that our results are explained by executives having co-opted the pay-setting process. That is, at least to some degree, executives are exercising influence over the board of directors—extracting compensation packages that exceed what would be expected in a competitive labor market.

Total compensation of all oil and gas executives in our sample is almost $1 billion per year, so the dollar value at stake here is substantial. Understanding pay-for-luck dynamics in oil and gas can also shed light on other industries where luck is less obvious, but often equally important. With median pay for U.S. CEOs nearly $12 million per year, executive compensation has become more complicated and important to understand than ever.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print