Yaron Nili is Assistant Professor at University of Wisconsin Law School. This post is based on his recent article, forthcoming in the Boston University Law Review.

Recent years have seen a push towards the separation of the roles of CEO and chairperson of the board. While many companies still maintain a combined CEO-Chair role, a majority of the S&P 1500 companies has separated the roles, and investors consistently express their concern that the dual CEO-Chair position jeopardizes the independence and effectiveness of the board.

Many of the proposals to separate the CEO-Chair role seek to install an independent chair and retain the current CEO; however, recruiting a new chairperson is only one way in which the separation of the CEO-Chair roles can occur. In my recent article, Successor CEOs, forthcoming in the Boston University Law Review, I explore a second means of separating these roles: one where the CEO-Chair relinquishes her CEO position but remains the chairperson, allowing the company to bring on a new CEO to take her place. This is what I label as the “successor CEOs” phenomenon. Take, for example, the case of Chipotle Mexican Grill. The founder and former CEO of the company, Steven Ells, served as Chairman-CEO from 2009 through 2016 but stepped away from the CEO role in late 2017 due to investor pressure; former Taco Bell chief executive, Brian Niccol, was named his successor. While Ells is no longer the CEO, he remains the chairman of the board.

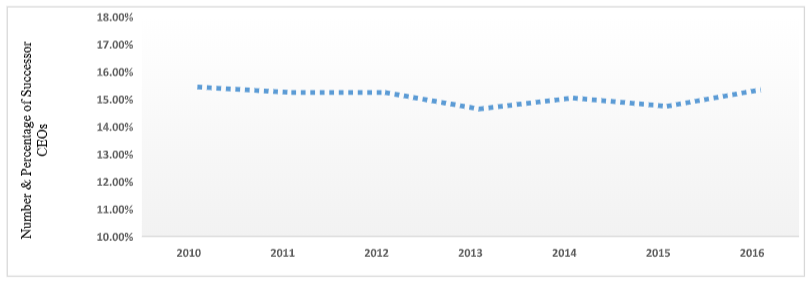

Chipotle is not an outlier. Using comprehensive data on all companies in the S&P 1500 for the years 2010 through 2016, my article reveals that a significant number of companies have a similar successor CEO structure. In 2016, for example, there were 217 (14.8%) companies in the S&P 1500 with a chairperson who had served as the CEO of the company in the past but no longer does so. This trend is sustained over time, as every year about 35-45 companies are making such a transition. In addition, while successor CEO structure is more common in mid and small cap companies it is still prevalent in S&P 500 companies with 13% of the S&P 500 companies having such a structure.

Figure 1. Successor CEO Board Structure in each FY

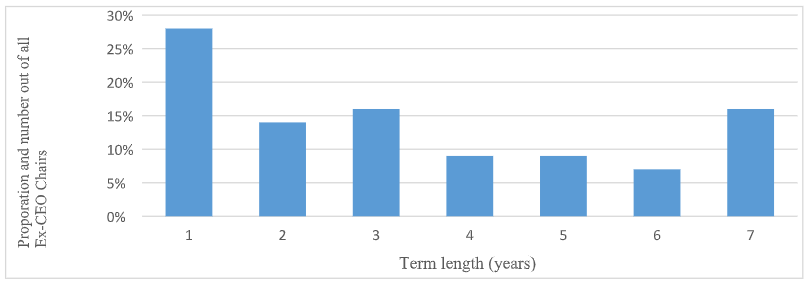

Importantly, the retention of the chair role by a departing CEO is not merely an effort to ease the natural “pass-the-baton” succession process, where the incoming CEO regains the chair position after a few months of wetting their feet. Figure 2 shows that during the years 2010-2016, only 28 percent of ex-CEO chairs served for one year or less, whereas 58 percent served for three or more years, and on a whole, the average term length for a chair in a successor CEO setting is 3.4 years. This suggests that in most cases, the departing CEOs retained their chair positions as part of a more permanent separation policy.

This second channel of CEO-Chair separation, one that does not involve the insertion of an independent chair, but rather focuses on the CEO-Chair relinquishing her CEO role while maintaining her chair title, has important corporate governance ramifications. Should investors view these companies similarly to those that transitioned to having an independent chair? Is the new CEO really free to run the company as she sees fit, or is she effectively controlled by, and operating under, the influence and clout of the former CEO, now chair? More generally, what benefits and concerns does this structure pose from business and corporate governance perspectives?

The article explores these normative implications, both from a traditional management structure prism as well as against the backdrop of the corporate governance case for board independence. The successor CEO phenomenon presents a tradeoff to companies, especially where the former CEO is also a controlling shareholder or the founder. On the one hand, allowing the former CEO to retain power through the chair role provides a significant outlet that may encourage the CEO-Chair to “pass the baton” to a new management team that is more qualified to take the company into the future. It also installs as the chair a person with a vast knowledge of the company, which would allow her to both contribute as a trusted advisor, and when needed, scrutinize management decisions more effectively. On the other hand, questions arise as to the ability of the successor CEO to act independently, and whether the departing CEO-now-Chair may actually retain control of the company, but in a more obscure, less optimal manner.

Similarly, from a corporate governance lens, while the successor CEO separation channel may reduce the incoming CEO’s authority over the board’s work, in many ways, it introduces an equally problematic concern—the possibility that the chair may maintain her grip and control of the company. A board led by the former CEO has the potential to exhibit even less independence and monitoring ability. The departing CEO-now-chair may enjoy a unique power through her position as chair, but she may just as well lack the motivation to monitor the CEO in a manner that would align with investors’ interests. This is particularly concerning since 76 percent of the companies that had a successor CEO in 2016 choose the successor from within, naming a long time employee as the CEO. In these cases, the CEO and the chair may act in unity—not truly independent of one another, consequently curtailing the ability of the remaining directors to scrutinize the actions of the CEO and the ex-CEO chair.

The successor CEO route of separation may also allow companies to camouflage themselves as good governance actors while in reality, their structure lacks the independence that institutional investors aimed to promote through the installment of independent chair. Indeed, 20 percent of the successor CEO companies actually declared the past CEO-now-chair as an “independent chair.” This designation is technically permissible once three years have passed from the date the former CEO left her position as CEO. Yet, it is not clear that passage of time after one has served as a CEO of a company can or should credibly reinstate her independence. Moreover, in many cases, companies with successor CEOs do not even appoint a lead independent director to counterbalance the lack of a truly independent chair. Indeed, 34 percent of the companies with a successor CEO structure had no lead independent director in place.

Finally, the transition of a former CEO to the chairman title alone can have an adverse impact on the incoming CEO. According to one study, CEO-to-chairman transitions can negatively affect replacement CEO performance 60 percent of the time, with 30 percent of those cases being “dysfunctional.” Having two leaders who are trying to “steer the same ship” may lead to inevitable friction that may result in deteriorating company performance.

Recognizing the benefits and costs of the successor CEO structure, the question of whether a successor CEO structure is beneficial may be company dependent. Notwithstanding, the normative analysis and the empirical findings of this article do provide some cause for concern regarding the drawbacks of the successor CEO structure.

One issue that investors, regulators, and stock exchanges may need to address is the treatment of chairs as independent even if they previously served as CEOs of the companies for which they now serve as chairs. Designating a former CEO of the company as independent director, immediately or even after the “cooling off” period, undermines the goal behind director independence designations and is particularly concerning when the person declared as independent is the chair of the board. This, in turn, necessitates a reconsideration of the independence requirements for chairs, and consideration by stock exchanges of potentially prohibiting companies from treating past executives of the company as independent chairs.

Second, where a successor CEO structure exists, it is important not only to have a lead independent director, but also to afford such director with sufficient powers to offset the control that the CEO and the chair may have over the board. In fact, the case of the ex-CEO chair is only an extreme example of the inadequateness of lead independent directors in curtailing the concerns of board capture by management. This capture concern is clearly present, and potentially aggravated, where the CEO and the chair positions are separate but held by company “insiders.” Therefore, investors and regulators should revisit the role that lead independent directors should serve in providing investors with a true watchdog in the boardroom, both in the larger landscape of companies with CEO-Chairs and especially in companies with a successor CEO structure.

Finally, the findings of this article should inform investors and proxy advisors that companies may have legitimate reasons for separating the CEO-Chair roles but also avoiding the appointment of an independent chair. As such, a binary expectation, and a push by investors for the installment of an independent chair may lead to sub-optimal results. For instance, companies that have a founder-CEO may benefit from utilizing this route in order to facilitate CEO refreshment. Similarly, companies who bring in a successor CEO from the outside could benefit from retaining the ex-CEO for the long term through the chair position. On the other hand, where the successor CEO is a long-term company executive, the benefits of keeping the ex-CEO diminish, while the concerns regarding the grip the ex-CEO chair may have on the company may increase. Investors and proxy advisors should therefore engage these companies specifically regarding their CEO-Chair relationship and the presence of sufficiently empowered independent directors.

The complete article is available here.

Print

Print