Steve Van Putten is senior managing director; David Bixby is managing director; and Jannice L. Koors is senior managing director at Pearl Meyer & Partners, LLC. This post is based on a Pearl Meyer memorandum by Mr. Van Putten, Mr. Bixby, Ms. Koors, and Matt Turner. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Paying for Long-Term Performance by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried (discussed on the Forum here).

Pearl Meyer’s annual “Top Five” publication provides a roadmap for boards that are seeking to get ahead of emerging issues. More than ever, we are seeing the compensation committee’s scope of influence expand, while much attention is being paid to how directors themselves are compensated. Measuring and rewarding performance—both financial and non-financial—based on the specific goals of each company continues to be a complicated endeavor. Meanwhile, decisions must be made within a complex and uncertain business and geopolitical environment.

Our five topics for 2019 follow the convention of previous years in that we are offering a balance of practical, near-term ideas, as well as future-looking topics for your consideration.

- Be Ready for An Expanding Compensation Committee Role. Broader-based pay issues (think CEO Pay Ratio and gender and other diversity-based pay inequities), talent development, and culture-related concerns are pushing the boundaries of traditional compensation committee responsibilities.

- Get More Comfortable with Non-Financial Metrics. They may not be right for all companies but given the increasing interest in non-financial metrics and the possibility that they could further your business strategy, a robust discussion on the subject should be included in your 2019 compensation committee’s agenda.

- Revisit and Refine Your Relative Total Shareholder Return (rTSR) Plan. TSR is probably here to stay but satisfying external stakeholders while maintaining any incentive value of an rTSR-based awards is challenging. Some companies are feeling pressure to modify these plans.

- Brace for Changes in Director Pay. Given the increased discussions regarding board diversity, education, and refreshment and additional board and committee responsibilities, committees may want to—or need to—rethink their director pay programs.

- Expect and Prepare for Unexpected Impact to Your Compensation Plans. Remember good plan design—and good executive compensation governance—includes planning for the unexpected. Inevitably there will be things that you haven’t fully anticipated, but thoughtful preparation for the “known unknowns” and brainstorming “black swan” events can help the board mitigate future risk.

Be Ready for An Expanding Compensation Committee Role

One of the biggest trends we’ve seen in corporate governance over the past two to three years is the expansion of “executive compensation” committee oversight. In fact, the term “compensation committee” is increasingly a misnomer. As part of our annual Pearl Meyer/NACD review of director compensation, we found that nearly 20% of the 1400 US public companies analyzed have formally expanded the purview of their board compensation committees to incorporate some aspect of leadership and talent. Committee names include compensation and management development committee; leadership and compensation committee; management performance committee; and people resources committee, just to name a few.

Overview is Broader and Deeper

More and more, the compensation committee is focusing time and attention on issues beyond the determination of compensation for C-suite executives, such as succession planning, corporate culture, and diversity and inclusion. Far from trying to second guess or micro-manage the senior management team, boards understand that these human capital issues present real, strategic business challenges, risks, and opportunities to their companies.

- Succession Planning and Talent Development: CEO succession has long been one of the key responsibilities of the board. We see leading boards expanding their purview beyond the C-suite, to include succession plans for other key positions, including select positions two or three levels removed from the CEO. Most boards already go through an annual “ready-now/ready-soon” review of successors to key positions. That said, in many cases, the process is tilted too heavily towards the status quo rather than the needs of the future. For example, while it’s considered best practice to have succession charts that identify ready-now candidates for key positions, committees should also have alternative succession chart(s) that contemplate i) the actual expected timing of retirements, and/or ii) changes in business/organizational needs. These alternative views can serve to highlight talent development or recruiting needs (e.g., ready-now executives who will be past their “expiration dates” when positions are likely to become open, or skills/experience gaps in the current management population needed to meet the changing business).

- Corporate Culture and Employee Engagement: Corporate culture is a bit like art—we may disagree about what is good, but we all know bad when we see it. However, historically these issues have been squarely in the no-fly zone for directors—under the sole purview of management—unless or until there was a major problem. Today, committees are looking to be more engaged in providing ongoing counsel and oversight. The recent examples of the negative business ramifications driven by toxic environments serve to convince directors that oversight of culture is just as important as oversight of business operations/strategy. But, given the episodic nature of board member interaction with the company, minding the corporate culture will likely remain the responsibility of management. Committee oversight tends to take the form of routinely monitoring trends and reports (e.g., engagement surveys, employee turnover statistics, exit interview findings, Glass Door reviews, etc.). In addition, many directors try to develop a better understanding of the corporate culture through individual efforts and activities (e.g., attending employee town hall meetings, “wandering the halls” before and after board meetings, individual site visits, etc.).

- Diversity and Inclusion: For many boards, their discussions regarding D&I started from a risk and liability perspective (e.g., how to insure against discrimination lawsuits, or concerns over possible reporting on gender pay equity). And #metoo reporting has further highlighted the potential corporate culture risks that can result from a lack of diversity among the management team. Without question, the committee has a responsibility to ensure that the company has policies and procedures in place to address any reported incidents and take remedial action as necessary. Beyond the risk aspects, however, companies increasingly recognize the advantages to being viewed as a leader on D&I issues. Numerous studies have concluded that diversity in the C-suite and boardroom results in stronger financial performance and returns to shareholders. At a broader organizational level, a reputation as an open and inclusive employer can be a competitive advantage in a tightening labor market. And more and more, consumers are considering good corporate citizenship as a factor in their buying decisions.

Practically speaking, the challenge for committees is making time in the annual calendar to address these issues in more than a check-the-box way. As companies look to ensure that new strategic human capital issues get the appropriate attention, we encourage committees to identify opportunities to streamline the more compliance-oriented parts of the annual agenda. In our experience, even seemingly simple things like executive summaries, materials in advance, and consent agendas can help to free up precious time for important strategic discussions.

Get More Comfortable with Non-Financial Metrics

Investors are increasingly asking companies to expand performance criteria beyond traditional financial yardsticks and increase the focus on—and investment in—non-financial drivers of long-term value creation. Implementing non-financial metrics as part of the executive incentive portfolio has its challenges, but if done correctly, the resulting balance of both lead (non-financial) and lag (financial) metrics may provide a more holistic framework to motivate and reward long-term performance. The top questions to ask when starting down this path are:

- Which non-financial metrics should be considered and for what program?

- Should non-financial metrics be a separately-weighted component or a modifier?

- What are the potential pitfalls in implementing non-financial metrics?

Consideration of Non-Financial Metrics

In addition to providing competitive compensation opportunities, a key objective of incentive programs is to signal, both internally and externally, as to what the company’s board and leadership view as important indicators of successful performance. Often, those indicators are based on financial performance objectives such as growth, profitability, and returns on invested capital. However, while those financial metrics are important measures of a company’s ability to execute on existing products and services, they are generally lagging indicators of performance and don’t specifically measure and reward attainment of key strategic value drivers.

In considering whether to introduce non-financial metrics and what types of metrics to incorporate into an incentive program, the following are questions to discuss at your compensation committee meeting:

- Have we identified key drivers of future growth and value creation?

- Are we able to effectively measure how we are viewed by our customers?

- Do we need to raise awareness as to the criticality of certain key strategic imperatives?

Not all companies will need to make this kind of change or need to move toward this at the same pace as others, but given the increasing interest and the possibility that it could further your business strategy, this topic should at a minimum be included on your committee’s agenda in 2019 and likely revisited frequently.

Measuring Non-Financial Performance

Assuming your company has decided to introduce non-financial performance objectives into your incentive plan, how should it be structured? First, it is most common to incorporate non-financial metrics into the annual program since it is easier and more impactful to set goals and measure performance outcomes on a yearly as opposed to a multi-year basis. Ideally, the non-financial objectives are short-term imperatives or areas of focus that will result in long-term value creation.

Another key consideration is whether to structure the non-financial objectives as a modifier to the financially determined incentive or whether it should be a separately weighted component of the incentive. Most companies use them as a modifier, which tends to be a softer measure of performance on those non-financial criteria since, often, the application of the modifier tends to be positive rather than negative. A related consideration is how quantifiable the measurement of the non-financial objectives is. The more subjective the measure, the more likely it is used as a modifier as opposed to a separately weighted component.

Potential Pitfalls

The biggest potential pitfall is that the use of subjective criteria tends to result in different views of the degree of attainment and thus potential for disagreement. Another is having too many non-financial measures, which can lead to a lack of understanding and dilution of importance. Finally, it is important to revisit the metrics annually and adjust as the company’s business strategy evolves.

Revisit and Refine Your Relative Total Shareholder Return (rTSR) Plan

Despite concerns regarding their effectiveness, it looks like rTSR-based incentive plans are here to stay. During the 2018 proxy season, over 50% of S&P 500 companies reported using rTSR in their long-term incentive plan and it’s not hard to understand the key reasons why:

- Relative performance metrics can help mitigate against the impact of industry volatility over multi-year periods in a way that absolute measures cannot;

- Peer selection and performance tracking is simpler for rTSR than it is for other relative financial performance metrics like EPS, EBITDA, or ROIC;

- rTSR is easily defensible, aligning pay outcomes with shareholder experience; and

- rTSR remains a core piece of the pay-for-performance models of both leading proxy advisory firms.

As some companies with these plans may have recently discovered, however, yesterday’s rTSR plan may no longer be sufficient to earn “full credit” with external stakeholders. Many companies are feeling pressure to modify existing plans to fit with “best practices” such as adding modifiers to account for absolute TSR performance or raising relative performance standards. So how should boards be thinking about the rTSR plan in 2019, as they seek to balance the concerns of external stakeholders with the desire to maintain the incentive value of their compensation plans?

The following questions should be asked to ensure your plan is still doing what you want it to do:

- What is the role of rTSR in our mix? If you adopted an rTSR plan in order to have a performance-based vehicle that provides incentives to outperform in up-cycles and down-cycles, be careful about how many additional modifiers you add to your plan. Every time you layer on an adjustment factor, you run the risk of getting further away from the original objective, and you run the risk of diluting the incentive value of your plan.

- Do we already have an absolute modifier built into our rTSR plan? If you are concerned that above-target payouts in years of poor absolute performance sends the wrong message, you may already have an absolute modifier in your plan. For awards that are denominated and settled in shares (as they are for most companies), the full market value of individual shares earned will move with stock price and will impact the realized value at vesting. In these cases, capping the number of shares earned in a down-cycle penalizes plan participants twice for the same tough industry conditions.

- Is absolute performance already captured somewhere else in our compensation program? For the vast majority of companies with an rTSR plan, that plan is not operating in a vacuum. Most companies already pay for absolute performance through the annual incentive plan, or with other long-term incentive devices like stock options or another absolute financial performance metric in the long-term incentive program.

- Has the payout schedule been properly calibrated? Before establishing more “robust” performance standards in your rTSR plan, consider the impact of any change on the target value. If you target the median of the market for pay opportunities, but want to shift your rTSR performance target from the 50th to the 60th percentile of your peers for example, it may be appropriate to adjust other terms such as the maximum payout opportunity in order to ensure that the expected value still aligns with your pay philosophy.

- Are we overthinking things? There are more nuanced ways to apply absolute TSR modifiers than simply capping payouts for negative TSR performance. Some companies opt for collars that set both a floor and a ceiling for different absolute TSR outcomes, while others adopt a matrix approach that can provide for varied payouts across a range of rTSR and absolute TSR performance levels. However, while nuance can help address both external and internal concerns, be careful not to become so clever that the incentive value of your program is lost completely to unhelpful complexity.

As you assess your plan design and answer the questions above, you may find that what you have is already working well and that the best alternative for you is to stick to your original plan and to sell that plan directly to your shareholders. However, if at some point you feel like your rTSR plan is causing you more trouble than it’s worth, with too many extra hoops to jump through, it may be time to start fresh. Maybe the right answer for you is to consider an alternative relative or absolute measure for your plan…or maybe it’s time for something even more revolutionary, like stock options!

Brace for Changes in Director Pay

Last summer, ISS announced that it would be adding a review of director compensation as part of its 2019 voting guidelines. ISS has since announced that it would defer “formal” assessment to the 2020 proxy season but will include their analyses in 2019 reports so that companies—and investors—can become familiar with methodology. Add to this new scrutiny the fact that many activist investors already use director (and executive) compensation as a stalking horse issue that demonstrates lack of independence on the part of the board of directors. This new ISS quantitative analysis will add fuel to that activist fire.

Director Compensation: Where We’ve Been…

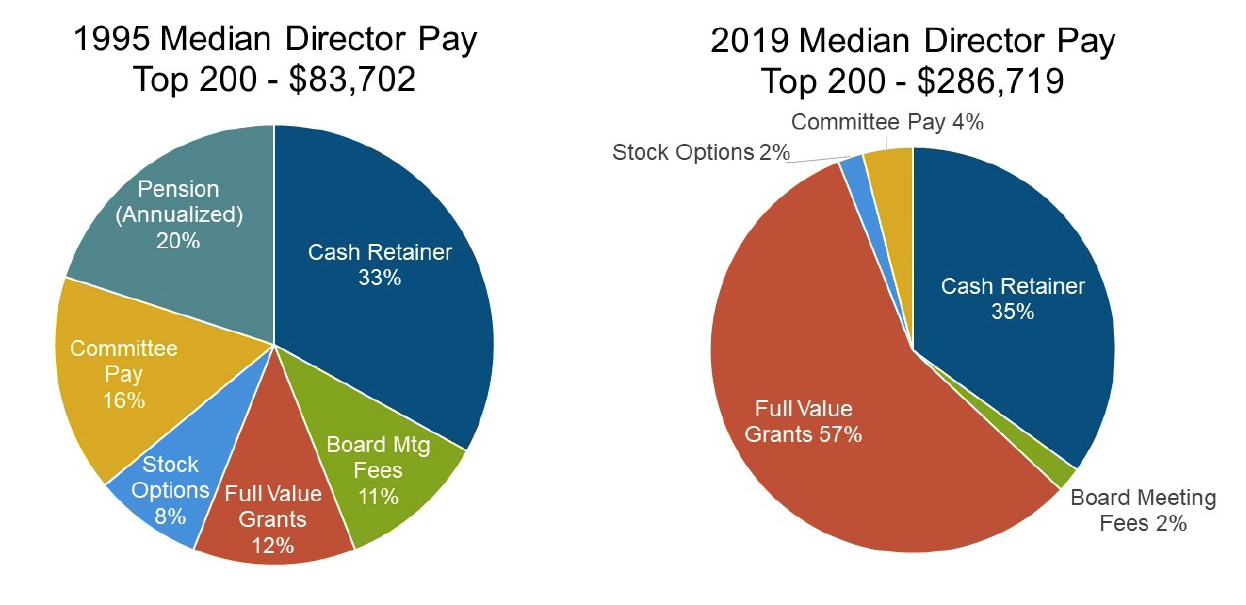

The structure of director compensation tends to be much less complex than executive pay, and annual changes in market practice are fairly incremental. But that doesn’t mean static. The comparison below provides stark illustration of the changes in director pay among the largest US publicly-traded companies over the past 25 years.

As noted above, median director pay has increased just over five percent per year over the past quarter century—a fairly modest growth rate that is not particularly noteworthy. But the chart clearly shows how the delivery of director compensation has been streamlined. The lion’s share of compensation now comes from the annual cash retainer and annual restricted stock grant. Of particular note:

- Only 10% of the Top 200 still use board meeting fees (compared to 85% in 1995).

- Only 7% of companies grant options (compared to 38% in 1995); in contrast, 97% now grant full value shares (compared to 53% in 1995). Furthermore, in 1995 only 11 of the Top 200 companies had share ownership guidelines; now in place at 93% of companies.

- While the majority of companies (58%) still provide some form of compensation to members of at least one committee, and virtually all companies (97%) provide additional compensation to committee chairs, the average value hasn’t actually increased much in 25 years, so it now represents a much smaller portion of the overall pay package.

- Director pension plans, which were offered by 70% of the Top 200 in 1995, no longer exist at any Top 200 company.

…And Where We’re Going

While many of these trends will continue, we’ve started to see some caveats and expect some new twists in the future.

- Median director pay will continue to increase at low-to-mid single digit rates, but the range in market pay may narrow even more. In 1995, Top 200 quartile pay (i.e., 25th and 75th percentiles) was roughly +/-20% compared to median. This year, the quartiles are only +/- 7.5% versus median. The new scrutiny on director pay will only put more pressure on “outliers.”

- As a result, we will likely see companies consider smaller, more frequent adjustments to director pay levels and we may eventually find that companies review and adjust director pay annually, as they do with executive pay.

- Companies will continue to eliminate meeting fees in favor of cash retainers, which are more suited to the increasingly fluid and individual nature of board member time commitment. That said, we have seen some companies incorporate contingencies to provide additional compensation (e.g., meeting fees, per diems, etc.) in situations where time requirements are significantly greater than “normal.”

- Companies will continue to favor full value shares over options for directors. Current thinking among governance experts is that full value shares are more consistent with the objective of conferring real stock ownership to directors to align their interests with the shareholders they represent. However, there are pockets of activists and private equity investors who believe directors should also be subject to pay-for-performance expectations. Others argue that since directors certify company results it could create conflicts if their pay were tied to performance. We expect this debate will intensify and may cause, at a minimum, renewed interest in options for directors—at least among smaller, or newly-public companies. Interestingly, while no companies among the current Top 200 have performance plans, in 1995 there were six companies in the Top 200 that had performance-based equity awards for directors.

- On the committee front, it seems that we may have hit the peak on differentiated pay, and the pendulum is swinging back. In fact, for the past two to three years, the majority of Top 200 companies have stopped providing committee compensation to members of all but their audit committees. The trend toward differentiation, which began as a result of Sarbanes-Oxley legislation, is being reversed in many companies under the premise that all committees bear different burdens and all board members make equal contributions to the whole. Lastly, we wonder if companies might consider how director pay programs could support board refreshment and diversity goals. For example, younger or first-time directors might benefit from a cash-equity balance closer to 50-50, or a guaranteed annual education stipend. To date, companies have increasingly relied on mandatory retirement (used by 81% of the Top 200 today, compared to only 20% in 1995) to address board refreshment. Maybe companies need to devise a “carrot” to accompany this “stick.” Consider the pension plans of old. They were designed to transition long-tenured directors off the board by providing a multi-year payout post-termination. Might there be a way to recreate this concept in a new, more shareholder-friendly way?

Looking ahead, board compensation levels will be under new scrutiny at a time when the demands on board members continue to intensify. Boards will have to think creatively to find the balance between offering a compelling package to attract qualified directors and keeping compensation totals within guidelines acceptable to shareholders.

Expect and Prepare for Unexpected Impact to Your Compensation Plans

These are turbulent times. From trade wars, tariffs, and tax law changes to major environmental events and the impact of global climate change, events external to businesses are buffeting financial results and impacting incentive compensation outcomes. These new challenges to your pay-for-performance commitment make this a good time to review your adjustment policies.

Even in “normal” times, there are plenty of occasions to consider use of discretion to adjust incentive outcomes. These occasions may include acquisitions and divestitures; unusual swings in commodity prices, exchange rates, or interest rates; lawsuit settlements or regulatory actions; legacy asset write-downs; windfall gains and the like. Your compensation committee should ensure it has thought through if, when, and how you might make modifications to the incentive plan before you begin an incentive cycle. Talk about the various scenarios by asking:

- What has been done in the past? Fairness for both management and shareholders begins with consistency and predictability. Understand your history of incentive plan adjustments. Much like that with the Supreme Court, stare decisis should be given due consideration. But with changing times, new approaches may be warranted. The corollary to this question is, “what precedent is being set?”

- Is the event unusual/extraordinary or is it the new normal? Truly one-time events might be treated differently, with greater emphasis on getting the right and fair outcome. But a new normal requires a greater focus on the impact such conditions will have on decision-making and the path to value creation. Insulating management from new economic realities they must manage can result in a chronic handicap to your business’ bottom line results.

- How might decision-making be influenced if adjustments are or are not made? The very purpose of incentive compensation is to align the interests of management with shareholders. As referenced in the last point, you must understand the decision-making signal being sent by an adjustment (or lack of one). Sometimes it makes sense to provide accommodations in short-term incentives, while sticking closer to bottom line results in long-term calculations.

- What is the magnitude of the event on incentives? Would an adjustment only result in a small, incremental change to the incentive outcome, or will it change a no-payout situation to a maximum payout (or something in between these cases)? Fairness and disclosure concerns may be different depending upon the magnitude of the adjustment.

Remember good plan design—and good executive compensation governance—includes planning for the unexpected. Thoughtful preparation for the “known unknowns” and brainstorming “black swan” events can help the compensation committee mitigate future risk, improve perceptions of fairness, and reinforce the commitment to pay-for-performance.

Moving Ahead

“Expect the unexpected” says much to summarize what we anticipate in 2019. We have already seen major compensation-related themes begin to emerge that are not on this short list. For example, the demand for addressing gender-based pay issues is only increasing, as is the appetite for non-financial metrics that are specific to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals. How to effectively plan for and manage long-term leadership development within an organization is taking on more urgency as companies struggle with both executive succession and an incredibly tight labor market overall. The long list goes on.

We propose that boards keep an eye on the horizon, but focus on the active, current issues that are most relevant for the continued growth, innovation, and healthy corporate culture of their organization. Not an easy task, yet one that compensation plans can help support with careful thought and attention.

Print

Print