Brandon L. Garrett is the L. Neil Williams Professor of Law at the Duke University School of Law. This post is based on his recent article, forthcoming in the American Criminal Law Review.

A new article, titled Declining Corporate Prosecutions, forthcoming in the American Criminal Law Review, describes the results of a series of empirical analyses of corporate prosecutions, focusing on what has changed under the new Trump Administration. Two years into the Trump Administration, newly collected data available on the Duke / UVA Corporate Prosecution Registry, allows one to assess what impact a series of new policies have had on corporate enforcement. To provide a snapshot comparison, in its last 20 months, the Obama Administration levied $14.15 billion in total corporate penalties—with 71 financial institutions and 34 public companies prosecuted. During the Trump Administration, corporate penalties declined. During its first 20 months, there were $3.4 billion in total penalties, with 17 financial institutions and 13 public companies prosecuted. Consistent with these data, this Article describes changes in written policy, practice, and informal statements from the Department of Justice that have cumulatively softened the federal approach to corporate criminals. This Article also describes continuity between administrations. A rise in corporate declinations, for example, represents a continuation of Obama Administration policy. A decline in use of corporate monitors similarly reflects prior policy.

For example, the steady and low level of individual charging in corporate cases, reflects an ongoing lack of success of efforts to prioritize individual prosecutions, exemplified by the 2015 “Yates Memo.” That policy, like others, has now been formally relaxed. An earlier empirical analysis of individual prosecutions accompanying deferred and non-prosecution agreements from 2001 to 2012, in my book, Too Big to Jail, found that individuals were prosecuted accompanying 89 of 255 agreements. In a more detailed follow-up study, examining data through 2014, and also describing outcomes in these federal prosecutions, the pattern was unchanged. Of 306 deferred prosecution and non-prosecution agreements with organizations, 34%, or 104 companies, had officers or employees prosecuted, with 414 total individuals prosecuted. Most were not high-up individuals. Of the individuals prosecuted, thirteen were presidents, twenty-six were CEOs, twenty-eight were CFOs, and fifty-nine were vice-presidents.

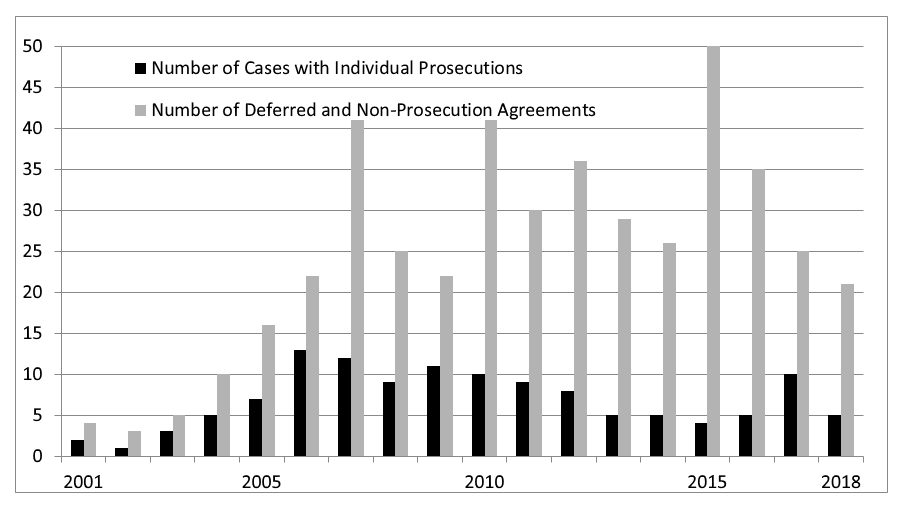

In a new analysis of post-Yates memo individual prosecutions accompanying federal corporate deferred and non-prosecution agreements, presented here to include further data from 2015 through 2018, the pattern has not noticeably changed. In the four years from 2015 to 2018, 59 individuals were charged accompanying deferred prosecution agreements. During the entire time period, from 2001 through 2018, there were individual prosecutions in 134 of 497 deferred and non-prosecution agreements, with 447 total individuals prosecuted. Of those, 34 were CEOs (typically former CEOs), 30 were CFOs, and 17 were Presidents. Thus, since the end of 2014, there have been thirty additional corporate deferred and non-prosecution agreements in which individuals were prosecuted alongside the firm. For the entire time period from 2001-2018, one observes individuals prosecuted alongside 27%, 134 of the 497 total agreements with organizations. Figure 4 in the Article displays these data, displaying both total agreements and the number of agreements in which individuals were charged for each year.

Figure 4. Individual Prosecutions Accompanying Deferred and Non-prosecution agreements, 2001-2018

The decline in individual charging is more apparent when one focuses just on recent years and not just the lower average over the entire time period. While it might seem notable that there have been 178 deferred and non-prosecution agreements during that time, the main reason why is the large number of non-prosecution agreements entered in 2015 with Swiss Banks as part of a program to offer lenient settlements as part of self-reporting and cooperation. None of those cases involved individual charges filed, including for practical and jurisdictional reasons; the banks tended to be small or mid-sized Swiss banks (albeit ones providing tax shelters to U.S. taxpayers).

If one focuses just on 2017-2018, however, one sees that any decline is less stark. There were forty-seven deferred or non-prosecution agreements in 2017-2018, and fifteen of those were cases in which individuals were charged, or 32%. That rate would be smaller (28%), though, if one takes into account the eight declinations in which no individuals were charged (in 2019, however, Cognizant Tech. received a declination in which individuals were charged). The result is that no meaningful change can be observed in the time period before or after the Yates Memo was adopted, and if anything, individual charging has declined in the years since it was adopted.

In addition to examining individual prosecutions accompanying deferred and non-prosecution agreements, I also examined plea agreements entered with public companies. After all, it is conceivable that individual prosecutions became more common post-Yates Memo in cases involving convictions of corporations. During the time period from 2001-2012, I found that 25 percent of public companies prosecuted had individual employees charged. Including cases from 2001 through 2018, I find that 48 of 169 public companies had individuals charged, or an only modestly higher 28%.

These data confirm the views of some observers who predicted early on that prosecutors would over time “retreat” from any strict or “all-or-nothing” approach towards the Yates Memo. Similarly, some observers, this author included, have argued that in context, the Yates Memo changes were not as dramatic as they appeared and that they might largely be aspirational. They could not or would not realistically be strictly enforced, due to the practical challenges in pursuing individual charges before setting a case with a corporation. Indeed, in announcing a change to the policy in Fall 2018, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein noted that the Yates Memo had not been strictly enforced: “we learned that the policy was not strictly enforced in some cases because it would have impeded resolutions and wasted resources.” These data bear out those observations. The Yates Memo may have never been fully implemented in the way the strict language in the U.S. Attorney’s Manual suggests. These policies are guidelines. They are not binding on prosecutors, and they seek only to inform decisionmaking. The experience with the Yates Memo suggests that such guidance and policies may not be fully implemented if there are practical and resource-based obstacles to doing so.

This series of DOJ corporate prosecution policy changes have been accompanied by important institutional shifts. For example, high-level vacancies within the DOJ and other enforcement agencies may compromise ability to coordinate resolution of complex cases. This Article concludes by proposing structural changes, such as an independent corporate enforcement functions, to enhance capacity and prevent pendulum shifts in the administration of enforcement. How we handle corporate crime goes to the root of power imbalance in the economy that produced the financial crisis. Ten years gone, if we still have not learned the lessons of the last financial crisis, then the next one cannot be far ahead.

The complete article is available for download here.

Print

Print