Josh Black is Managing Editor, and John Reetun and Eleanor O’Donnell are Financial Journalists at Activist Insight Ltd. This post is based on an Activist Insight memorandum by Mr. Black, Mr. Reetun, Ms. O’Donnell, Jason Booth, Iuri Struta, and Dan Davis. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Dancing with Activists by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, and Thomas Keusch (discussed on the Forum here); The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here); and Who Bleeds When the Wolves Bite? A Flesh-and-Blood Perspective on Hedge Fund Activism and Our Strange Corporate Governance System.

2019: An Overview

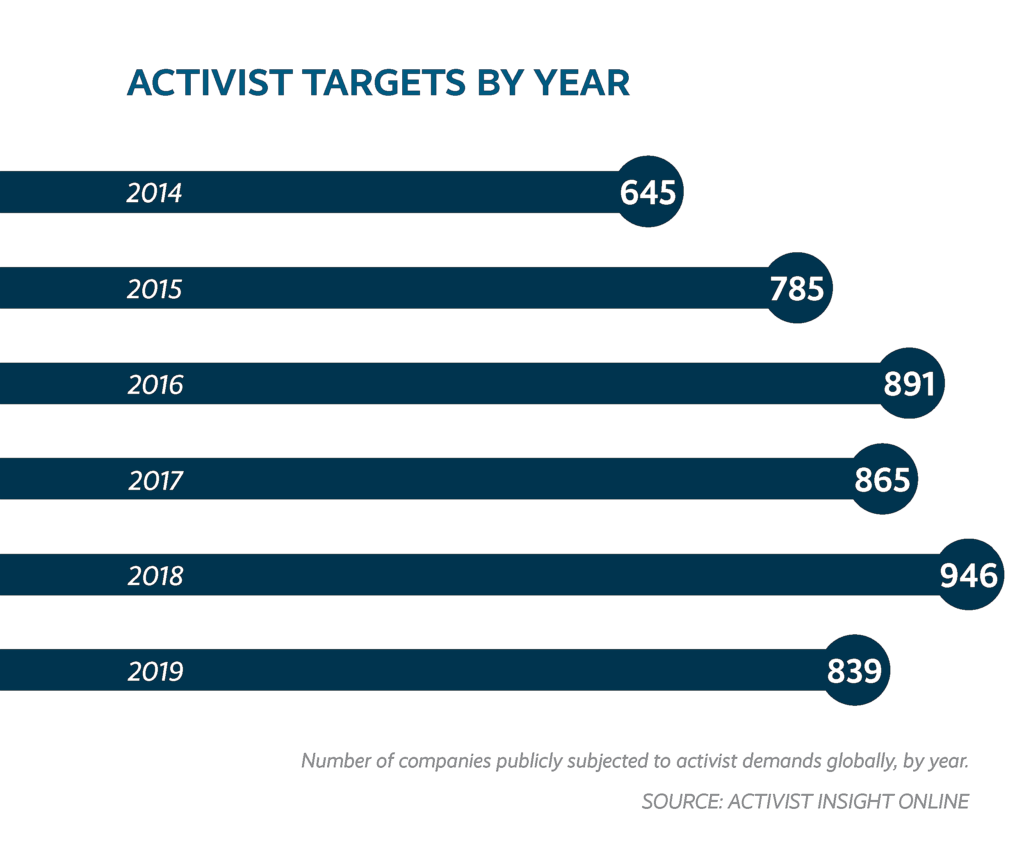

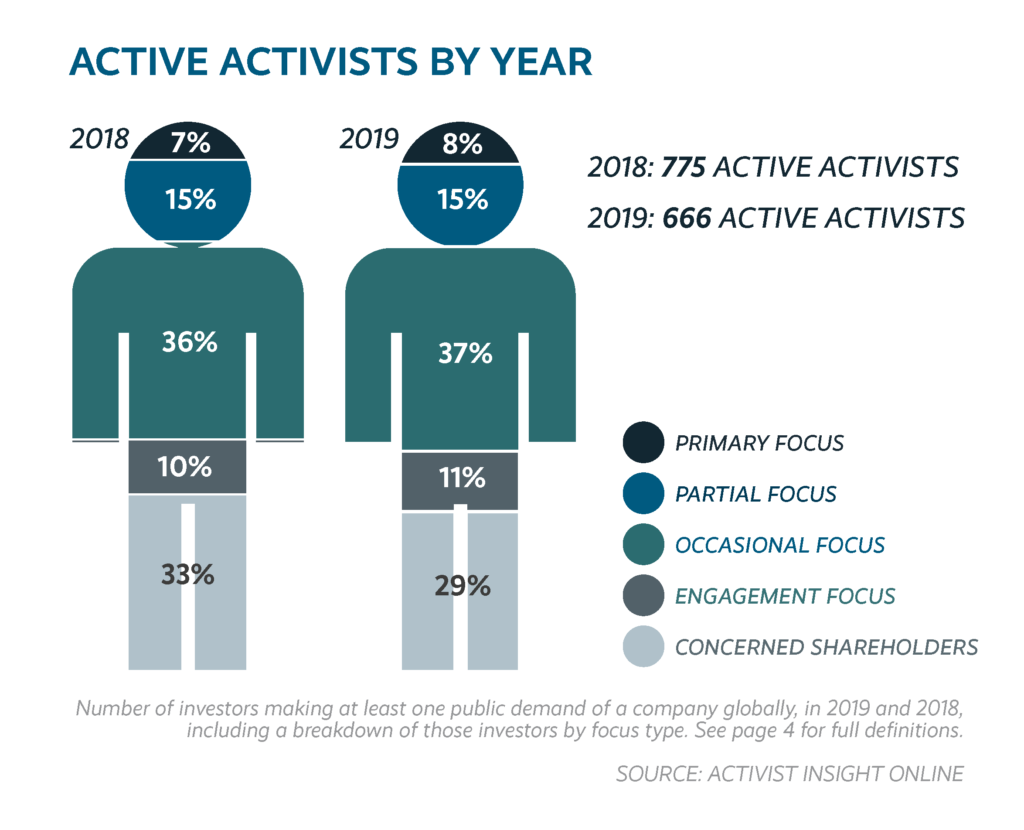

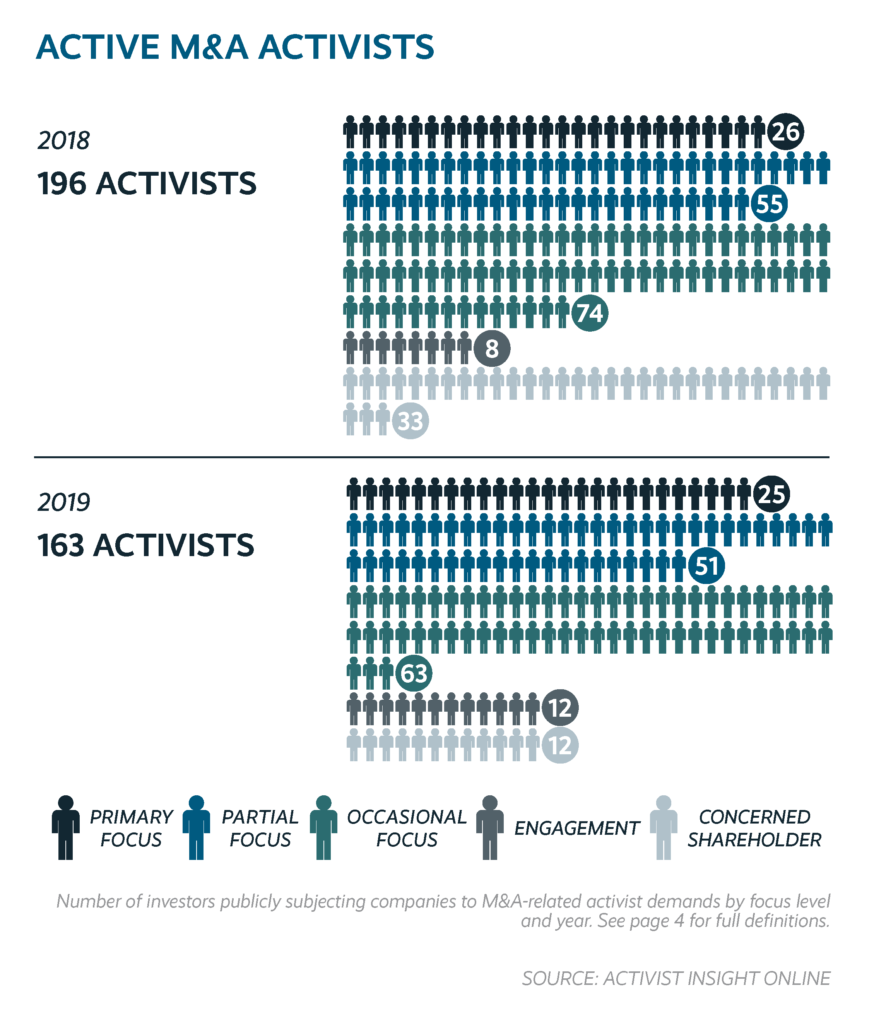

By some measures the slowest year since 2015, 2019 might look like the end of that boomlet. Although not the first down year in recent memory (2017 was too), the 839 companies publicly subjected to activist demands worldwide and the 666 investors making those demands were both four-year lows.

Yet the type of activist involved belies that impression. In 2015, 32% of investors making public demands had a primary or partial focus on activism. In 2019, the comparable figure was 23%. Concerned shareholder groups have taken up a lot of the slack but the activist toolkit has become frequently used by institutional investors and occasional activists too. In these pages, we make the case that private equity firms are increasingly being drawn into competition with activists that requires them to ape some of their strategies.

For years, onlookers have debated how much room activism has to grow. On the one hand, there will always be laggards—relative underperformers. On the other hand, many speculated that the “low-hanging fruit” was mostly picked over, forcing activists to adopt more operational strategies.

Perhaps a combination of the time involved in developing more robust investment theses and an evolving fundraising environment that prefers single-idea funds will limit the number of opportunities some activists can exploit. In the future, we may see more activists that look like Mantle Ridge, which launched its second fund and invested in Aramark in 2019. On the other hand, fund-based activists like Starboard Value and Elliott Management have found plenty to do, even if the latter may be busier on the debt side before too long.

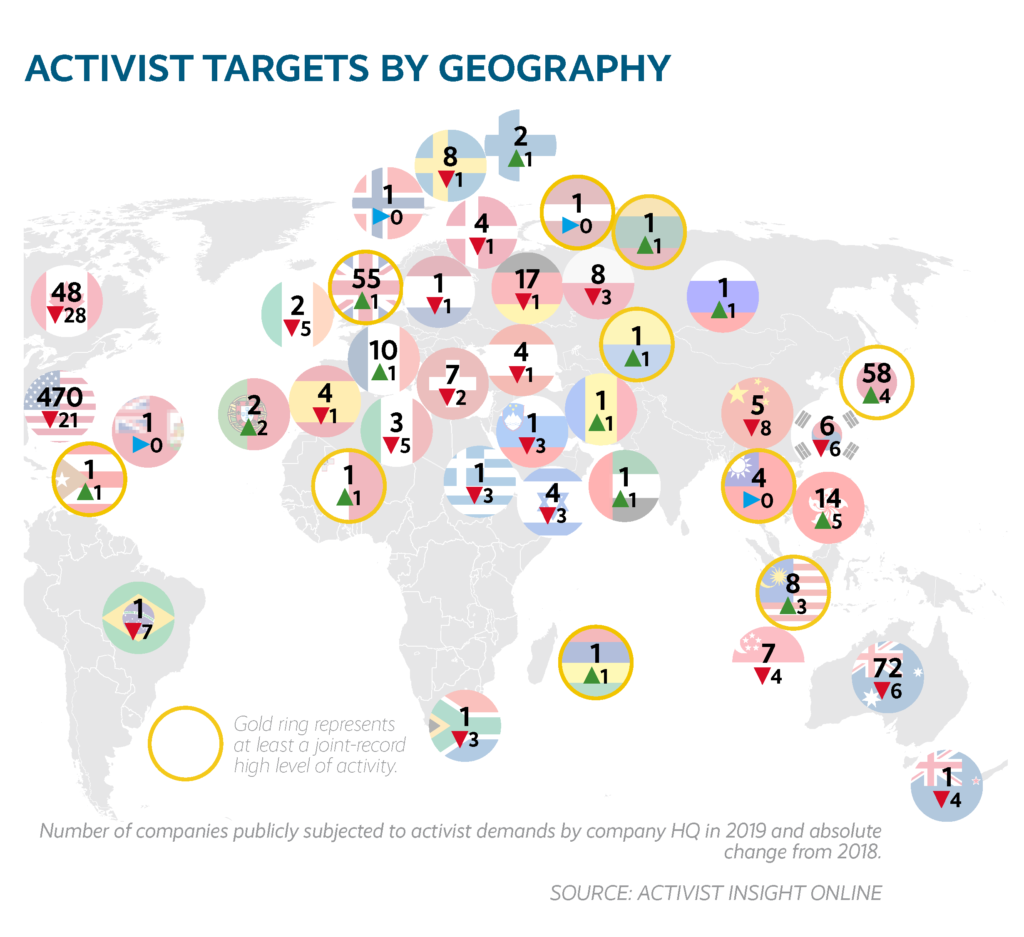

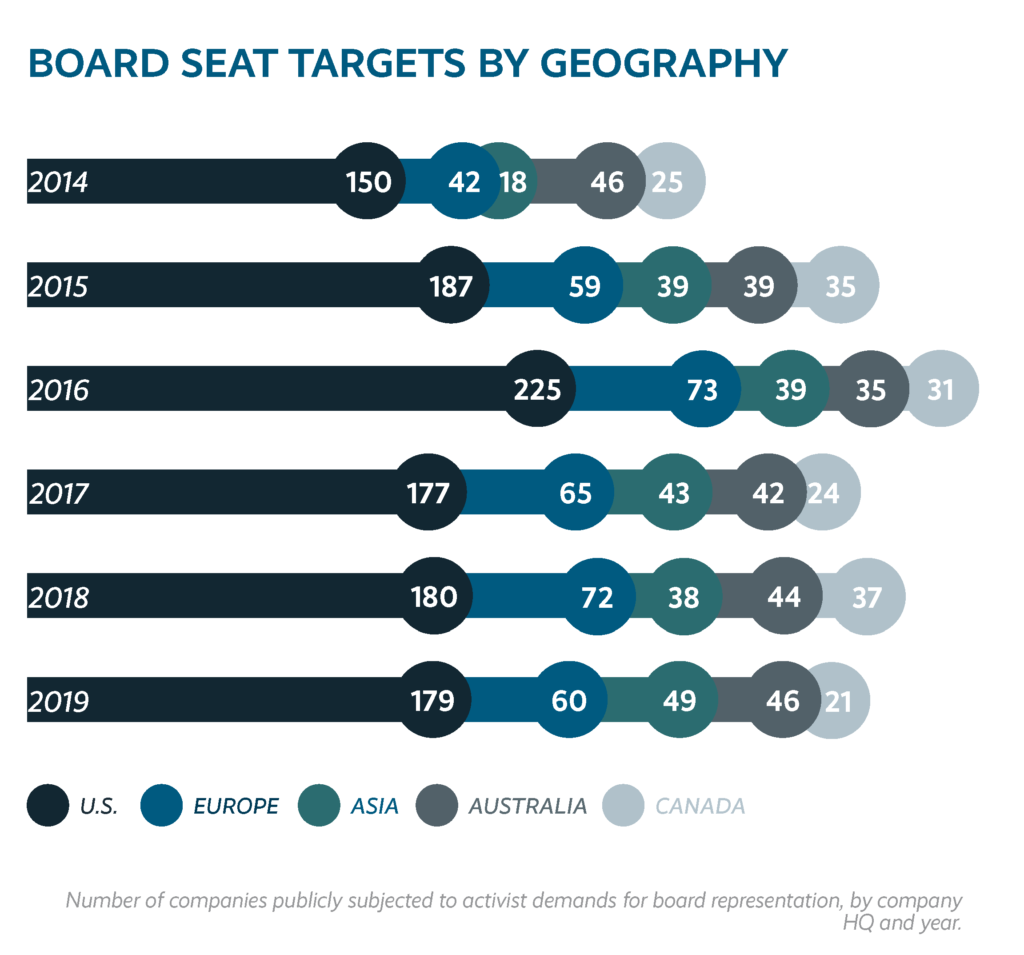

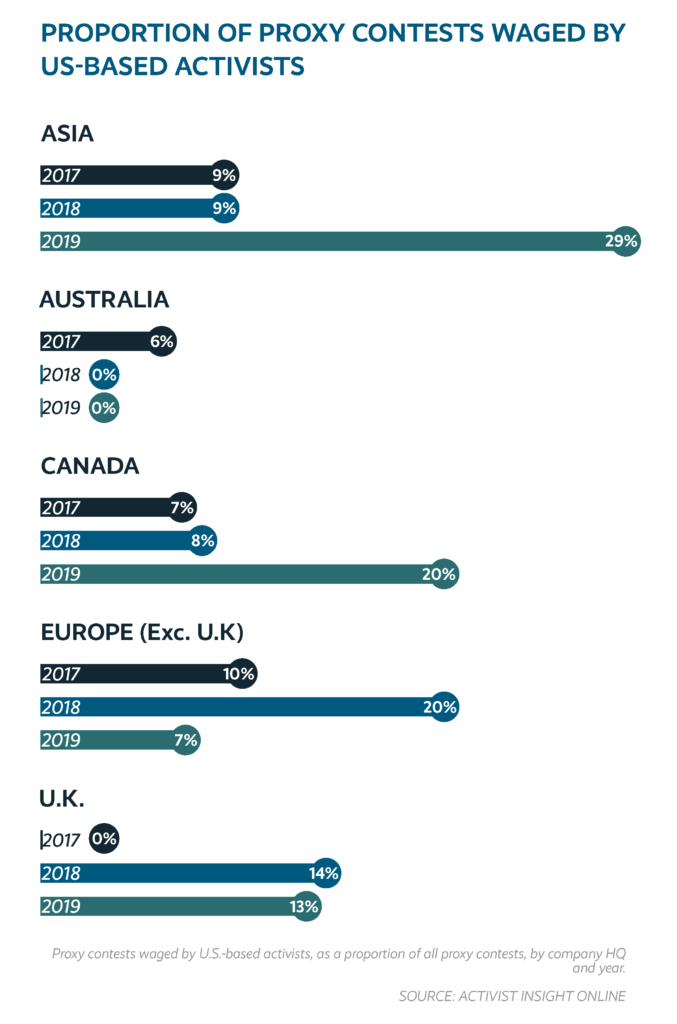

Another solution is to go abroad. The number of non-U.S. companies publicly subjected to activist demands by American investors increased sharply starting in 2015 and has remained at elevated levels. Many markets have seen a rapid development in business practices and particularly activist defense industries as a result. An increase in settled demands for board seats in Japan and the U.K. in 2019 may be a sign of increased sophistication or of pressure, given both also saw an increase in contested meetings.

U.S. activists retreated from overseas activism somewhat in 2019 compared with 2018’s recent peak. The exception was Japan, where attention was focused in a dramatic proxy season. Indeed, Japanese companies represented between 2% and 3% of activist targets globally (including by local investors) between 2013 and 2016. In 2019, they represented 7%, behind only the U.S. and Australia.

Then again, 2020 could be a year of rebirth for dedicated activists after a fortifying rally in the markets that many were able to ride. Activist Insight’s Follower Returns, which measure total shareholder return performance, suggest the annualized total return for primary and partial focus activists was 17.7% in 2019, ahead of that for all activist positions and more than three times the median return of occasional activists.

Perhaps fortified by those returns, a quieter 2019 proxy season in the U.S.—fewer contested meetings, more settlements—gave way to a busy second half of the year and an increase in consent solicitations. That could set 2020 up as a year to watch. By contrast, 2020 could be a year for activist short sellers, who increased their activity in 2019 for the first time since 2015 (coincidence?) and saw improved performance. Wherever the action is, it won’t be boring.

2020: An Outlook

With borrowing so cheap, any company can get a loan to buy back stock or acquire a competitor, ValueAct Capital Partners’ Jeff Ubben said recently. Unlike the San Francisco-based impact evangelist, other activists will have strong opinions about which option boards should take and will continue to explicitly oppose empire-building M&A, with a streak of breakup activism. In particular, environmental activism has proven a popular lever in the utility space for ValueAct and Elliott.

Environmental and social activism was a less influential theme in 2019 while the market was soaring, but it isn’t going away. If the proxy fight at Pacific Gas & Electric represented the first to incorporate these issues, 2020 might see the first proxy fight or CEO targeting campaign over a company’s environmental impact.

Japan and the U.K. were attractive markets for activism in 2019 and should be again in 2020. U.S. activists might also stray into Australia, but more will use earnings misses to find things to do at home. Breakup plays could be the best way to exploit high valuations.

Debt overhangs in the energy sector and the impact of the election cycle on healthcare may force activism toward tech and consumer stocks. Crowding might ensure a second successive down-year and greater focus on existing portfolio positions at the expense of new investments.

A large private equity fund might run its first semi-public campaign. Hostile and opportunist takeover bids will pick up as the election approaches.

A rising market is a good excuse for CEOs and activists to share the credit, where incremental changes can be conceded, and investors might view board seats as restrictive if there is the prospect of a sell-off. However, the punishment for companies that underperform their own predictions will be severe. Expect friendly gentlemen’s handshakes at a few large companies and an increasingly warlike footing in the small- and mid-cap space.

As companies have used advance nomination deadlines and delays to neuter some of the impacts of proxy fights, so activists have gone looking for new ways to cut the knot. Consent solicitations and books and records demands allow for a public relations campaign with teeth, although so far, the latter has not delivered on expectations.

Break It Up

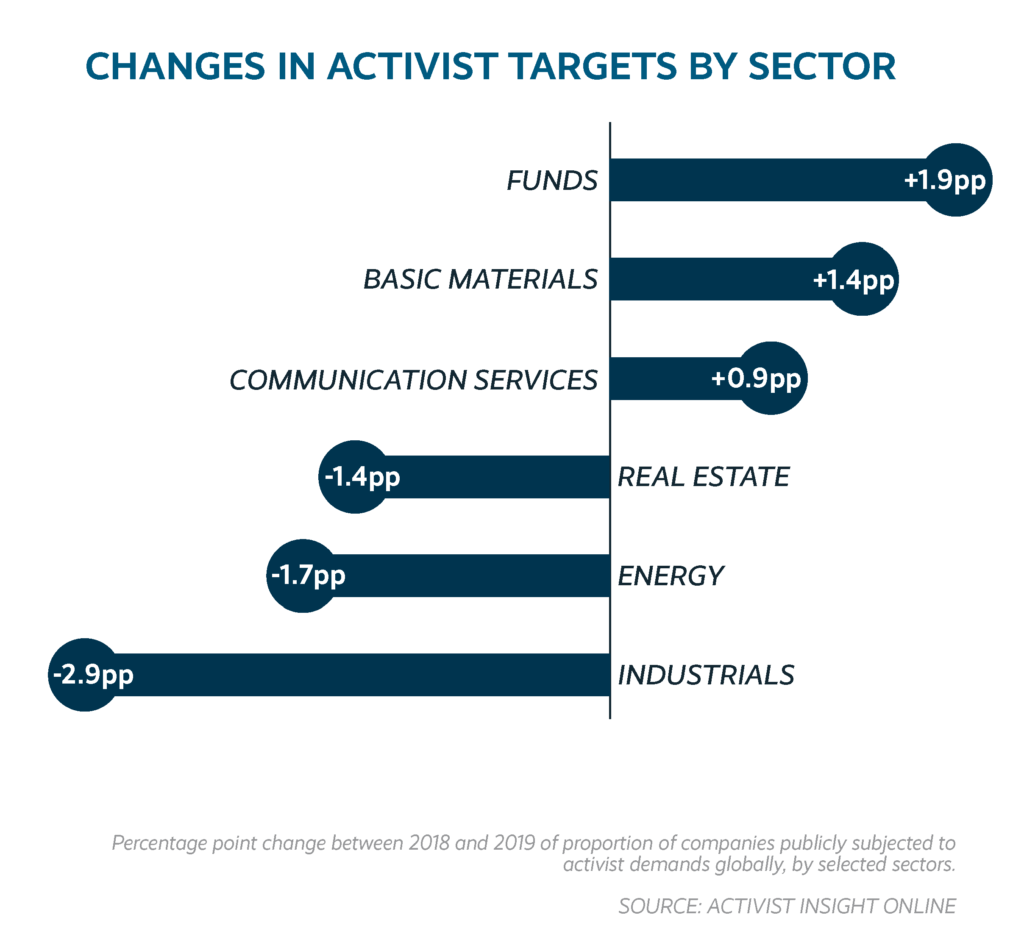

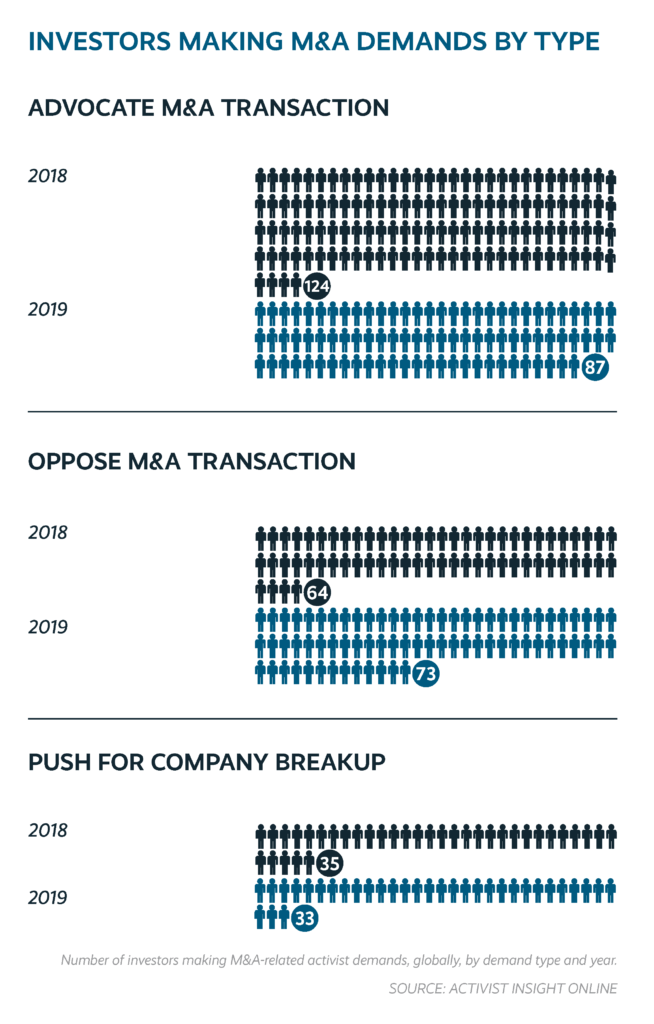

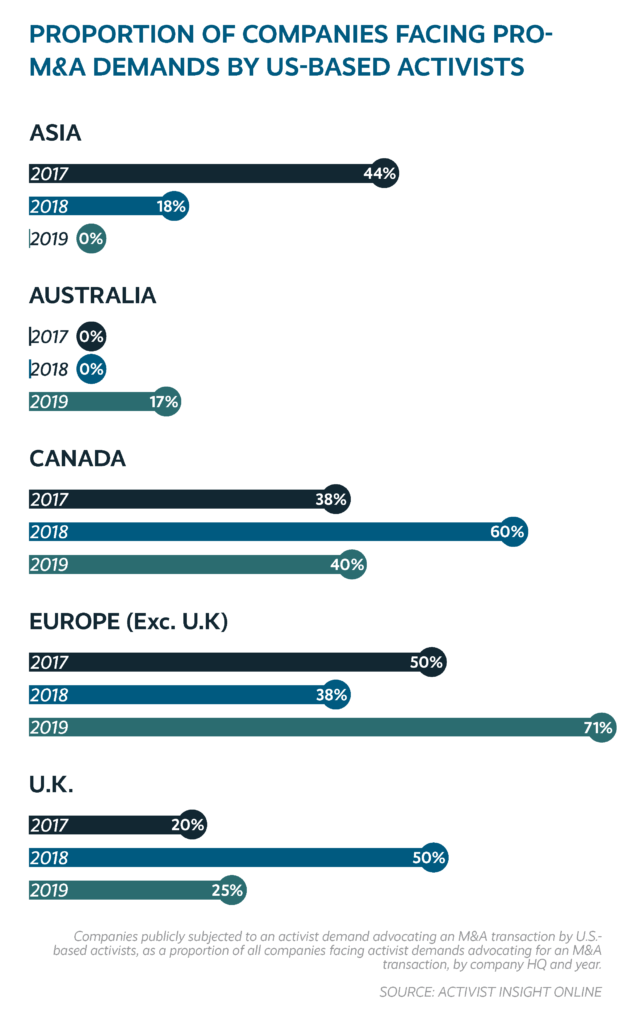

Opposition to M&A and breakup campaigns were prominent in 2019 as activists sought to navigate a toppy dealmaking environment.

While the U.S. saw the lowest number of companies publicly pushed into M&A since 2013, dragging down the overall number of M&A activism targets, above-average deal opposition dominated headlines. M&A-related activism is “now essentially a permanent fixture of the capital markets,” David Whissel, executive vice president at MacKenzie Partners, said in an interview for this report.

Confidence in the market may have been a factor, judging by the rising number of demands that companies break up. A record number of companies were subjected to such demands worldwide, rising two years in a row from a shaky 2017.

Playing Hard to Get

Overall opposition was most notable in the U.K. and Europe, where 21 companies saw deals opposed. Canada was stable in 2019 with six companies facing opposition to M&A deals. A slight dip in the U.S. saw the number of companies facing public demands opposing M&A fall from 28 in 2018 to 25 in 2019—still above the near-term average.

Such campaigns can lead to a bump in the stock price—as at Hudson’s Bay Co.—or force companies to justify their deals with additional information—as at Inmarsat. According to Whissel, they also demonstrate that profits are not always the priority. Indeed, Cat Rock Capital spurned a cash deal for the U.K.’s Just Eat that was preferred by fellow occasional activist Eminence Capital, in favor of a stock-for-stock merger with Takeaway.com that gives Just Eat’s shareholders a majority stake.

Investors “are scrutinizing deals more closely,” Whissel said, with criticism against “growth for the sake of growth.” Occidental Petroleum’s $55 billion takeover of Anadarko Petroleum, involving pricey financing from Berkshire Hathaway, angered asset manager T. Rowe Price Group and led Carl Icahn to threaten a proxy contest that could run into 2020.

Look, Don’t Buy

Eight U.S. companies saw acquisitions opposed by one of their own shareholders in 2019, the highest since at least 2013. The tactic all but disappeared elsewhere in the world. “Given the high levels of stock prices of many public companies, there’s likely going to be a substantial amount of opposition to deals,” Alfredo Porretti, managing director at Greenhill, told Activist Insight.

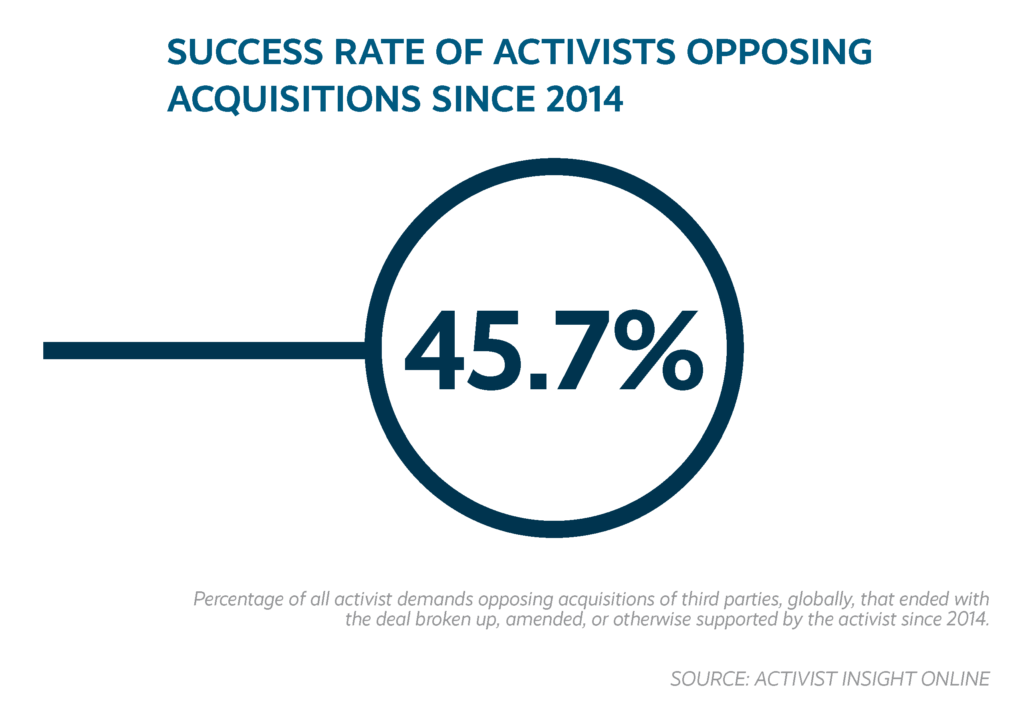

Such tactics can still pay off. Paulson & Co. opposed Callon Petroleum’s sale to Carrizo Oil & Gas and succeeded in changing its terms. But that was an outlier in 2019, where outcomes were divided almost equally between success, failure, and activists withdrawing their demands. Across the prior two years, more than half of activist campaigns against acquisitions globally were at least partially successful.

Notably, Starboard Value’s call for Bristol-Myers Squibb to break off its engagement with Celgene failed despite a vigorous campaign when both proxy advisers supported the deal. Though the activist made the case for a full operational overhaul as a third option, investors owning both Bristol-Myers and Celgene shares and the uncertainty of throwing out the deal made for an uphill battle.

Despite the significance of that fight, most market participants expect a continuation of the trend in 2020, so long as M&A markets hold up. “We’re still nearly in the same place,” Goldman Sachs’ Managing Director Pete Michelsen told Activist Insight. “Activists would rather companies sell right now and aren’t buyers. You’d expect more activism against buysides or mergers of equals.”

Offboarding

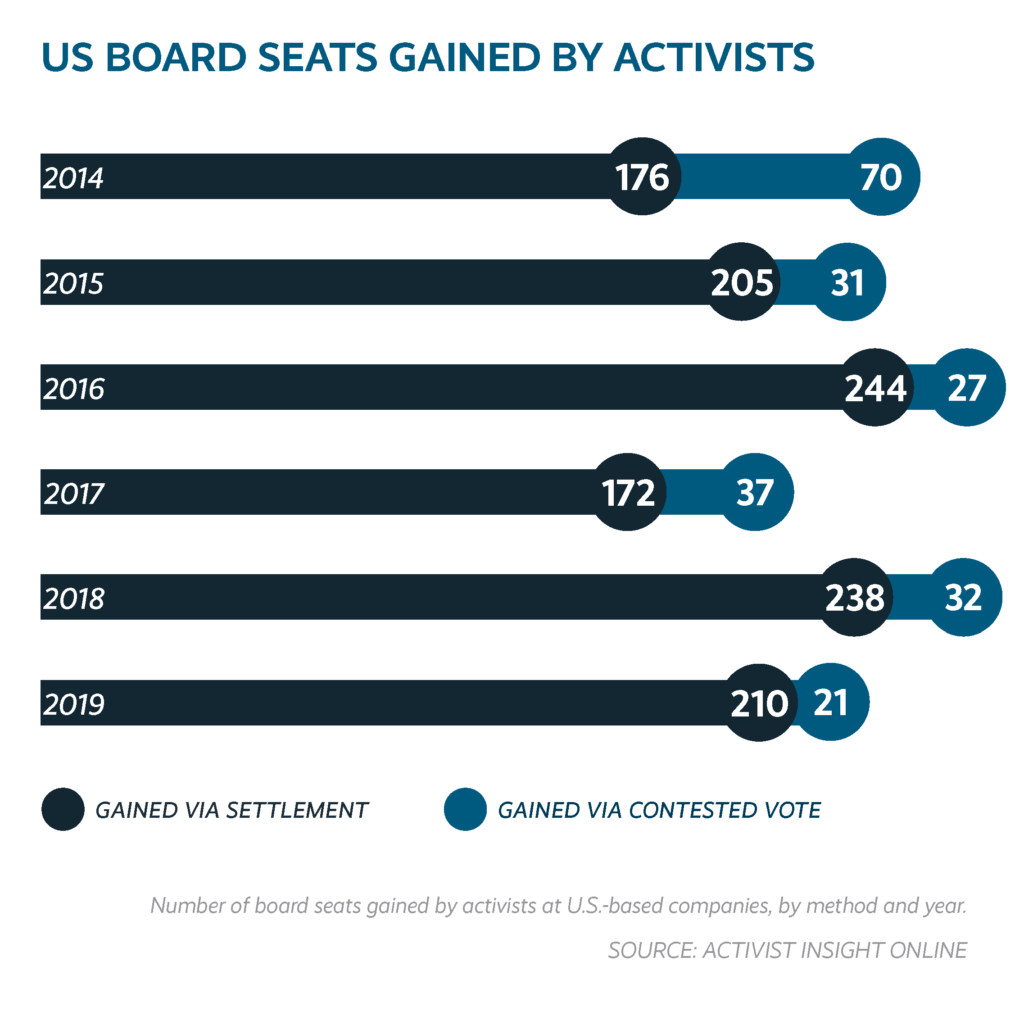

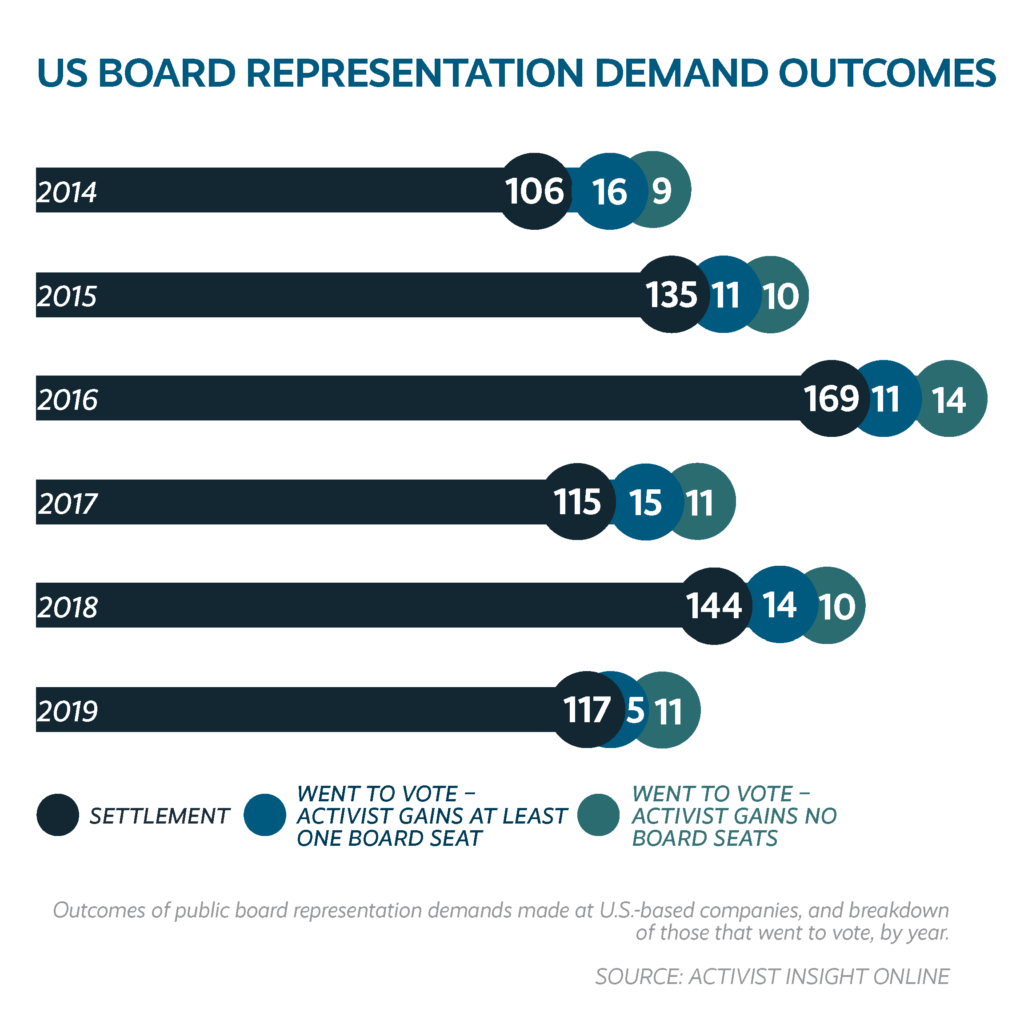

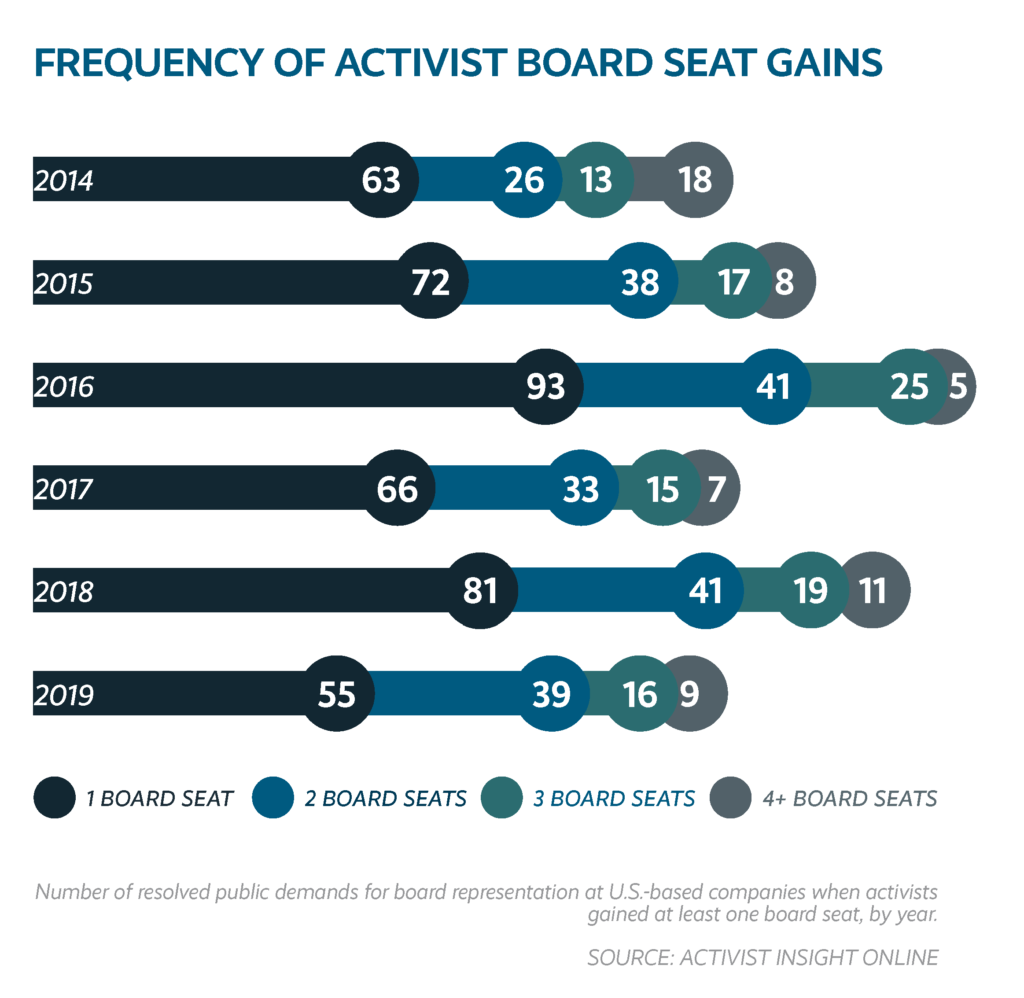

The 179 U.S.-based companies that received public demands for board representation from activists in 2019 marked a five-year low, accompanied by a dearth of proxy contests and speculation that activists were looking for more flexible arrangements with their targets. The 231 board seats won fell short of the 246 averaged by activists since 2014.

Standstills Backtracking?

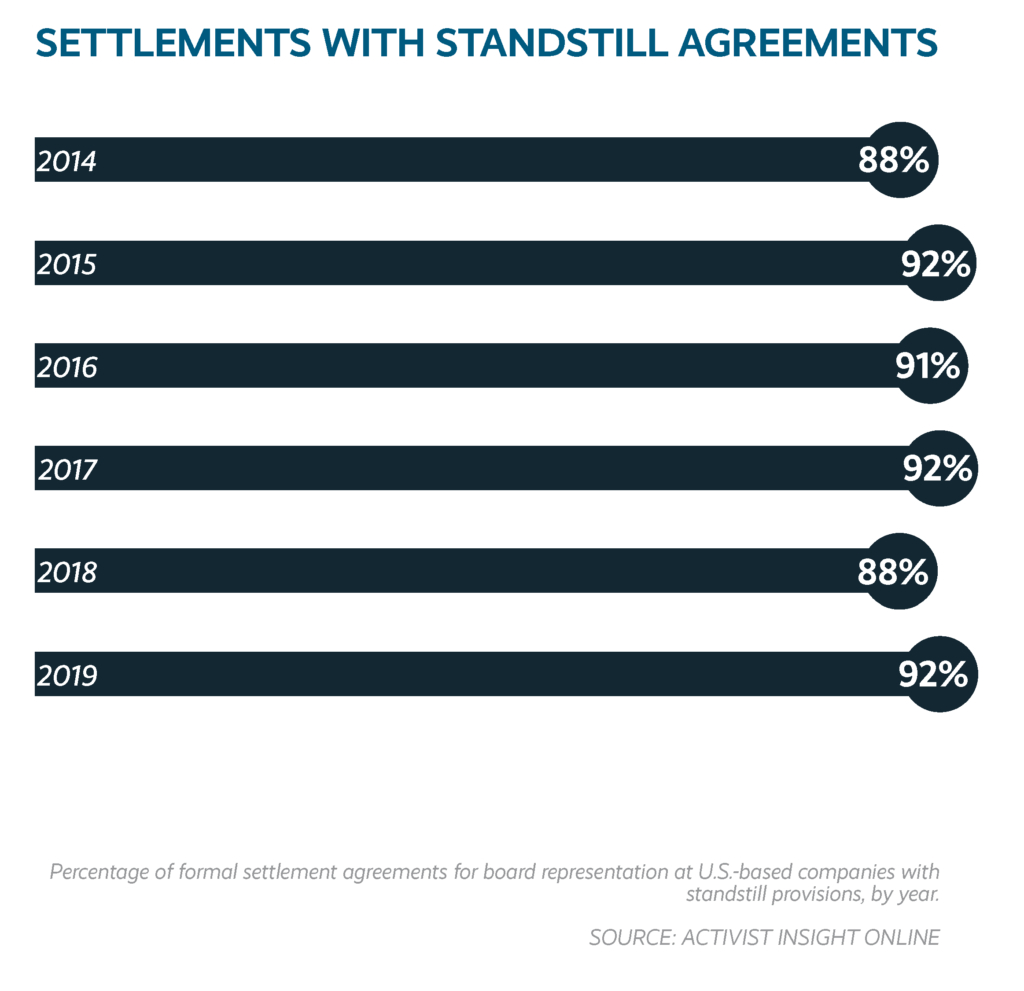

Concessions to activist investors without binding standstills by the likes of Emerson Electric, SAP, AT&T, and Marathon Petroleum gave rise to a view that more informal settlements were on the rise. If so, that would be a big change. In an academic article covering the years 2000 to 2013, Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, and Thomas Keusch described standstills as “the most important and almost universal concession” of settlements.

Evidence for the rise of non-standstill settlements is mostly anecdotal, however. Activist Insight Online data show the proportion of formal settlement agreements containing a standstill rose from 88% in 2018 to 92% in 2019. And while activists did sometimes shy away from explicit demands for board representation, Spotlight Advisors’ defense adviser Greg Taxin argues that, “For the most part, companies are going to insist on a standstill if an activist is going to get special treatment or a say on board composition or strategy.”

The non-standstill settlement may be a bluff. Indeed, months after Marathon announced plans for a leadership change and breakup, the company signed a cooperation agreement with Elliott Management, complete with standstill, and agreed to add a new director. ValueAct Capital Partners ended 2019 with a non-disclosure standstill at Citigroup and not the board seat it had been expected to take.

“Most activists are looking for a catalyst to move the stock, whether it’s a public statement or a formal settlement,” Stifel Managing Director Juan Bonifacino told Activist Insight. And while noting that activists are become more creative about how they create that catalyst, he added that, “For funds that have relatively longer investment horizons, board seats are an attractive way of pursuing that catalyst.”

A Year Without Fights

Proxy fights going to a vote at U.S.-based companies dropped precipitously in 2019, falling by one-third from a year earlier to 16—the first time below 20 since at least 2013. Companies won 69% of votes, ceding just 21 board seats.

“2019 experienced fewer proxy fights that went to a vote, in part because investors put forth ideas that would be very well accepted by other participants in the market,” Okapi Partners CEO Bruce Goldfarb told The Activist Insight Podcast in December. “Where we still had proxy fights were the situations where the sides were so far apart that they couldn’t reach an obvious conclusion.”

Those fights that did go the distance were typically by more inexperienced activists. Veterans such as Starboard Value and Elliott Management busied themselves with more innovative tactics, while Occidental Petroleum’s nomination deadline closed before its annual meeting, leaving Carl Icahn to wage an ultimately ineffective consent solicitation. Newcomers Bow Street Capital and Rice Investment Group won seats at Mack-Cali and EQT respectively—the latter in a ringing demonstration that the universal ballot can still deliver overwhelming board change. By October, the outlook was bright enough for Doug Braunstein’s avowedly pacifist Hudson Executive Capital to launch its first-ever proxy contest, at USA Technologies. Following a legal battle, the fight will take place in April 2020.

Settlements for the Win

Other factors behind settlements included exhaustion and the rising costs of litigation. At least two fights—at Argo Group International and Texas Pacific Land Trust—ended up settling after being unable to proceed to a vote.

Though fewer in number than in 2018, the 117 settlements at U.S.-based companies accounted for 72% of board campaign outcomes, up slightly from 2018’s 70%.

Us and Them

U.S. activists made public demands at 64 companies based outside of the U.S. in 2019, down from 87 a year earlier. Even so, an abrupt halt is unlikely.

Asia

Settlements for board seats involving ValueAct Capital Partners at Olympus and King Street Capital at Toshiba highlighted the strides U.S. activists have made in Asia, while Third Point Partners also received a notably less hostile response to the resumption of its campaign at Sony after a five-year hiatus. Although Sony’s management rejected the suggested separation of its semiconductor business, the stock has been a runaway success in 2019, justifying Daniel Loeb’s campaign.

“There continues to be interest in doing things abroad,” Pete Michelsen, a managing director in Goldman Sachs’ activism defense team, told Activist Insight for this report. “From a fundamental perspective, Japan remains a clear opportunity. It’s just the pathway with shareholders that’s unclear.”

Indeed, excitement about the Japanese market saw U.S. activists make public demands at a record 11 companies. Across Asia, the number of U.S. targets was just one below 2018’s record.

In their enthusiasm, U.S. activists also threw off a self-enforced conservativism, participating in seven of the 24 proxy fights resolved across Asia in 2019, (up from an average of 2.8 per year), and five of Japan’s total of 14.

That may have been inspired by domestic upstarts shaking up management, says Alfredo Porretti, an activism defense banker at Greenhill & Co. in New York. “Domestic activists should bridge the cultural gap for foreign ones.”

Europe

U.S. activists were less likely to take the bait in Europe, where they were behind three proxy fights in 2019 even as the U.K. saw an upsurge in fights by domestic activists. And though Sherborne Investors and Coast Capital were both unsuccessful at Barclays and FirstGroup’s ballot boxes, respectively, each forced significant changes in approach from their targets.

For the most part, activists that have made the trip across the pond in recent years have tempered their approach, especially since ValueAct Capital Partners negotiated its way onto the board of Rolls-Royce Holdings in 2015. That campaign, which seemed to come to a close in 2019 as Bradley Singer left the engineering company’s board, introduced the U.K. to standstill agreements of a kind common in the U.S. But Trian Partners needed nothing of the kind to persuade Ferguson to spin off its U.S. division.

“There was a maturity in terms of the U.K., where boards are realizing that if they have a serious engaged shareholder, they need to respond to it and respond to it quickly,” says Andrew Honnor, managing partner at Greenbrook Communications.

Although Elliott Management continued to push into Continental Europe, including with a campaign at German software giant SAP led by the investor’s New York office, interest in the U.K. held up much better.

“We get very polarized views in the U.S.—some don’t want to touch the U.K., can’t get their heads around Brexit, others think Brexit is overdone, there’s huge value,” Honnor said, adding that the return of a Conservative majority in December’s general election could spur dealmaking. “You get a lot of views that U.K.-listed stocks with an international component look cheap.”

U.S. activists may also temper their demands that companies sell themselves. In 2019, they made no such demands in Asia and just one-quarter of the U.K.’s push for M&A demands, although that could be explained by the size of targets required to lure activists to foreign shores. “The level of comfort in terms of ability to perform adequate ‘due diligence’ is going to be lower for a foreign activist, but if you can find companies that have a pedigree or global footprint, you’re not going to be as concerned,” Porretti concluded.

Less Private, More Equity

As the private equity space becomes crowded, anecdotal evidence suggests its players are increasingly using the tools of activist investing as fear of repercussions recedes.

Elliott Management’s adoption of take-private deals is widely considered to have put pressure on some private equity funds, even when the activist has partnered with industry stalwarts. In 2019, Elliott showed for the first time that the strategy could be a response to the short-lived effects of an activist campaign. Its private equity affiliate, Evergreen Coast Capital, teamed up with Francisco Partners to take LogMeIn private in a $4.3 billion deal, two years after Elliott’s representative had left the board and it had exited the stock.

In the past 18 months, activist funds Trian Partners and Engaged Capital reportedly considered taking Papa John’s International and Medifast private, respectively. Papa John’s instead received a strategic investment from Starboard Value—another private equity-like move—and no bid has yet emerged for Medifast. In Canada, Catalyst Capital Group rivalled an insider buyout of Hudson’s Bay Co., using a tender offer to build its stake, but withdrew when the management group upped its offer.

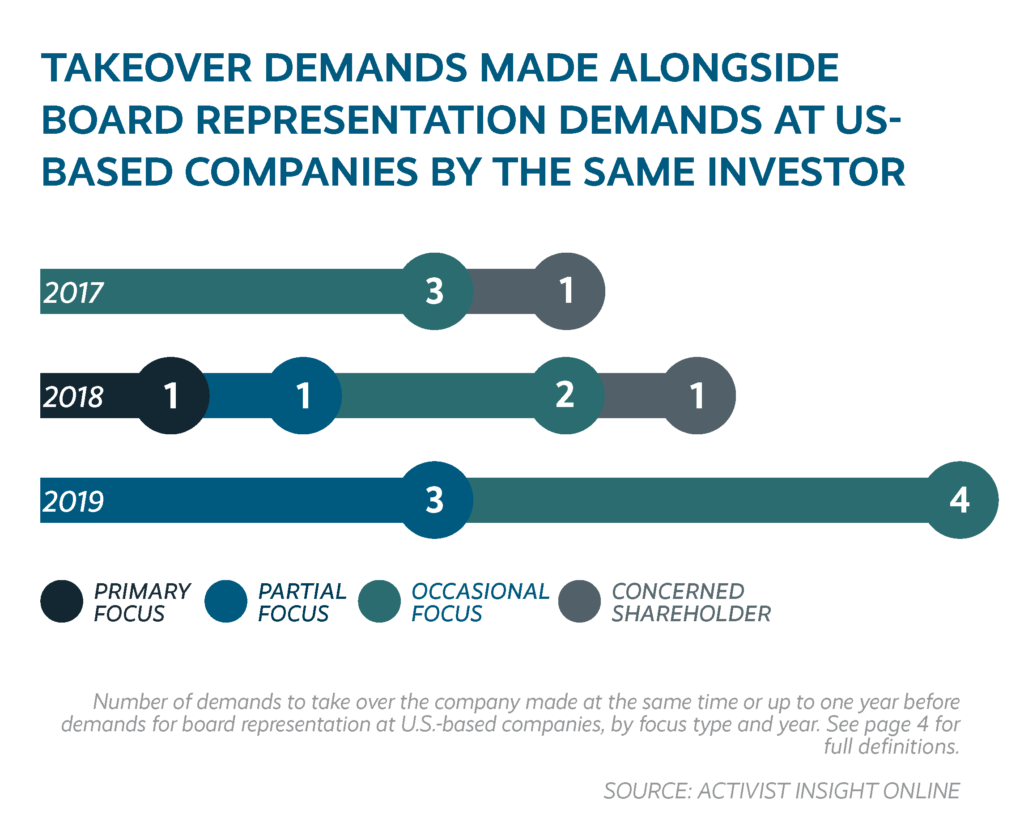

Retaining Trust

In a sign that hostile approaches may be on the increase, data from Activist Insight Online reveal that seven U.S. companies received demands for board representation at the same time or shortly after a takeover bid from the same investor, the highest since at least 2013 when records began.

Outright proxy fights by private equity firms are so far uncommon. As with traditional activists, many board campaigns end in settlements. In 2019, Altaris Capital Partners placed co-founder Daniel Tully on the board of Tivity Health and Capital Point inked a settlement with Can-Fite Biopharma, as part of which the fund was appointed as a consultant to advise Can-Fite on capital raisings, potential deals, or finding “suitable” investors. A two-year agreement between Deutsche Bank and Cerberus Capital Management ended discordantly in the same year, highlighting the difficulties of such relationships in turnarounds.

Nonetheless, private equity firms are realizing that “a more aggressive approach will not necessarily preclude them from earning management’s trust in a buyout,” MacKenzie Partners Executive Vice President David Whissel said in an interview.

While Whissel outlined that there are contractual and cultural limitations on a private equity fund’s ability to wage proxy contests or hostile takeovers, he sees similarities with operational activist strategies. “The amount of research and due diligence that goes into each investment, the long-term nature of each project, and the focus on using different capital allocation and operational efficiency levers to drive returns—it’s understandable that private equity investors would begin to borrow certain tactics from activists,” he says.

Natural Progression

Innisfree Chairman Arthur Crozier sees the movement of private equity into activist investing as natural and board representation as an effective way to bring about change. “As Willy Sutton said when asked why he robbed banks: ‘because that’s where the money is,’” he told Activist Insight. “Private equity is now very crowded… expanding into activism provides a wider range of targets.”

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print