Alma Cohen teaches at Harvard Law School and Tel-Aviv University School of Economics, and Moshe Hazan and David Weiss teach at Tel-Aviv University School of Economics. This post is based on their recent study. Related program research includes their article with Roberto Tallarita on The Politics of CEOs, available here and discussed on the Forum here.

In a new study placed on SSRN, Politics and Gender in the Executive Suite, we investigate the relationship of CEOs’ political preferences (as reflected in their political contributions) with the prevalence and compensation of women in leadership positions at U.S. public companies.

We find that CEOs who favor the Democratic Party (“Democratic CEOs”) are associated with the presence of more women in the team of non-CEO top executives (“the executive suite”). To explore causality, we use an event study approach and show that replacing a Republican CEO with a Democratic CEO is accompanied by an increased female representation in the executive suite.

To further explore causality, we examine whether CEO political preferences are associated with gender diversity in the boardroom and find no such association. This lack of association is consistent with CEOs’ preferences having less influence over gender diversity in the boardroom than the executive suite because CEOs have less power over the appointment of directors who supposed to supervise the CEO than over that of executives reporting to the CEO.

Finally, examining the gender gaps in the level and performance-sensitivity of executive compensation we documented in the literature, we find that they are driven by companies headed by Republican CEOs and disappear or at least diminish under Democratic CEOs.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the relationship between the incidence and compensation of females among companies’ top executives and CEOs’ political preferences. Significant separate literatures exist on both subjects, and our work seeks to contribute to each of them.

Below is a more detailed account of our analysis:

To investigate our subject, we examine all U.S. companies ever listed in the S&P 1500 during the period 2000-2018. Our analyses draw on data about the personal political contributions of CEOs put together for a companion paper (Cohen et al., 2019). Following the literature, we assume that contributing significantly more to one of the major parties reflects a personal preference for this party. We combine our data on CEO political preferences with data on the gender and compensation of non-CEO executives.

We start by showing, using an OLS analysis, that companies led by Democratic CEOs are associated with a significantly higher fraction of female executives than those run by Republican CEOs. In particular, a Democratic CEO employs 13% more female executives than a Republican CEO does, controlling for company characteristics and company fixed effects. This effect is statistically significant.

There are a number of reasons why Democratic CEOs and Republican CEOs may have different preferences or attitudes toward female executives:

- Democratic and Republican CEOs might have different perceptions about women’s relative skill at business;

- Democratic and Republican CEOs might differ in their support or opposition to gender diversity and gender pay equality;

- Democratic and Republican CEOs might have different exposure to career-focused women in top positions and in the network opportunities they have to hire such women.

- To the extent that CEOs prefer to work with executives sharing similar political views, because women tend to support Democrats more than men, CEOs’ preferring like-minded executives might lead Democratic CEOs to be more willing than Republican CEOs to hire female executives.; and

- Democratic CEOs might be more open to changes, which adding women into the executive suite would introduce, than Republican CEOs.

Alternatively, there may be a problem of omitted variable bias that drives our results. That is, there may be omitted company characteristics that lead companies to hire both a Democratic CEO and more women in the executive suite.

To explore whether the association is at least partly driven by CEO political preferences, we use an event-study approach in which the event is the replacement of a CEO. We find that prior to the replacement of a CEO, regardless of CEOs’ political preferences, there is no noticeable trend in the executive suite’s gender diversity.

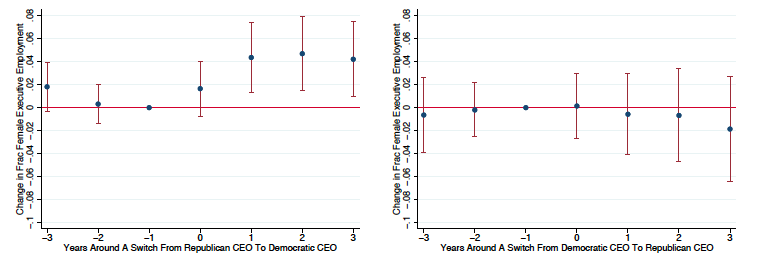

However, when the CEO changes, a switch from a Republican CEO to a Democratic CEO produces, compared with a switch to another Republican CEO, an increased female representation in the executive suite on the order of 40% over three years. This effect is statistically significant. By contrast, a switch from a Democrat CEO to a Republican CEO produces, compared to a switch to another Democratic, a 13% decrease in female representation in the executive suite over three years (though this decrease is not statistically significant due to the small size of the sample). Figure 1 displays the above patterns:

Figure 1. Event Study

Note: The left panel shows the change in the fraction of executives who are female around the time of a switch from a Republican CEO to a Democratic CEO. The right panel does the same for a switch in the opposite direction. The dots show the point estimates and the bars represent 95% confidence intervals around the estimates. 0 is the year in which a CEO is replaced.

To further explore whether the association between CEO political preferences and female representation in the executive suite is at least partly driven by CEO preferences rather than fully by omitted variables, we examine the presence of more women on the corporate board. To the extent that the association between Democratic CEOs and women in the executive suite is driven by omitted company characteristics that drive the choice of both a Democratic CEO and more women in corporate leadership, Democratic CEOs should also be expected to be associated with more women on the board.

By contrast, if the association between CEO political preferences and women in the executive suite is driven at least partly by CEO preferences, the association between Democratic CEOs and more women on the board should be weaker or even non-existent. CEO preferences are likely to have less influence on the choice of directors than on the choice of member of the executive suite for two reasons: First, CEO have more power over appointments of top executive reporting to them that over the appointment of directors overseeing them. Second, corporate decision-makers face discretion-reducing pressure from institutional investors to appoint women to the board (but do not face similarly strong pressures with respect to the executive suite).

Using both OLS analysis and an event-study approach, we find no evidence that CEO political preferences are associated with the gender composition of corporate boards. Whereas this evidence is merely suggestive, these findings are consistent with CEO political preferences being at least partly responsible for the identified association between such preferences and women in the executive suite.

Turning to the gender gap in compensation, we document that female executives are paid about 7-10% less than their male counterparts. This gender gap in compensation levels is comparable to what has been documented in the literature. However, this pay gap largely disappears under Democratic CEOs. Statistically, we cannot reject the hypothesis that there is no gender pay gap in the compensation of non-CEO top executives under Democratic CEOs. Thus, our findings indicate that the gender pay gap documented in the literature is driven by companies headed by Republican CEOs.

We next examine the gender gap in compensation structure, using three standard measures of the performance-sensitivity of compensation. We find that these measures are lower for female executives than for their male counterparts. However, we show that these gender gaps in pay structure largely disappear in companies headed by a Democratic CEO.

The findings of our study indicate that CEO political preferences play an important role in both female representation and gender pay gaps in the executive suite. Therefore, future research on female representation and gender pay gaps should take CEO political preferences into account.

While our analysis suggest that CEO political preferences have some influence on female representation and gender pay gaps in the executive suite, our evidence does not speak to the relative roles of the several possible reasons for such an association that we noted above. Further work on this issue would be worthwhile.

Our study is available here, and comments would be most welcome.

Print

Print