David F. Larcker is the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business and Brian Tayan is a Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This post is based on their recent paper.

Introduction

We recently published a paper on SSRN, The First Outside Director, that examines the individual chosen by private and public companies as their first outside director.

Little is known about the process by which pre-IPO companies select independent, outside board members—directors unaffiliated with the founder or investor groups. Private companies are not required to disclose their selection criteria or process. They are also not subject to public listing requirements that stipulate independence standards or impose specific monitoring obligations through committees and executive sessions. Instead, board choices are driven largely by company insiders (such as the founder, management, and investors) in consultation with advisors and affiliates to address specific strategic, leadership, or operational issues facing the company. Even the timing of when to invite an external director to the board tends to be discretionary. The result is that a startup company goes from having a closely controlled board comprised entirely of shareholder representatives, to one with unaffiliated outside directors who have equal and independent voting rights, with no standard road map for making this transition.

Here, we look at when, why, and how private companies add their first independent, outside director to the board.

Why An Outside Director?

Companies recruit an outside director to supplement the knowledge and network of personal contacts that the company’s founders, investors, and managers have about managing a business in a specific industry. The challenge that companies and boards face is how to prioritize the issues requiring attention and identify an outside professional with the requisite skills. The list of potential criteria is vast. Directors are expected to help with strategy, oversee management, refocus managerial attention on critical items, advise on internal system development (IT, HR, finance and accounting, etc.), refine marketing and pricing strategies, mediate customer acquisition and business partner development, contribute to talent recruitment through personal and professional networks, provide access to additional financing, and prepare for a potential IPO or sale, while showing the proper levels of commitment, engagement, and professionalism and not overstepping management. All these tasks cannot be accomplished by any one person.

One manual for startups categorizes professional directors by the contribution they make to the firm. The first type are reputation directors, those who bring industry expertise and market credibility because of their name recognition. The second type are active directors, those engaged in the details of board work and ensuring fiduciary obligations are satisfied. The third type are supplemental directors, those who bring functional expertise in specific areas where the company needs development. Once the board is fully established, each of these should be represented on the board. But which type of director should be recruited first?

Research on public company boards offers only modest insight into outside director selection and impact. The most relevant finding is that directors with related-industry expertise contribute positively to performance. Dass, Kini, Nanda, Onal, and Wang (2014) find that companies whose directors have related-industry experience trade at higher valuations and have better operating results. Faleye, Hoitash, and Hoitash (2018) find that directors with industry expertise contribute to product innovation and firm value. Masulis, Ruzzier, Xiao and Zhao (2012) show that directors with industry experience contribute to performance, CEO oversight, earnings quality, and investment. Adams, Akyol, and Verwijmeren (2018) find that, even though companies recruit directors with a variety of skill sets, performance and decision making improve when director skill sets are less diverse and have more commonality.

At the same time, personal factors might contribute to director quality. Adams and Ferreira (2007) argue that it is optimal to recruit boards that are friendly to management: CEOs are more likely to share information with friendly boards and, in return, receive better advice; at the same time, an informed board provides more effective monitoring of management. Khanna, Jones, and Boivie (2014) argue that, while companies benefit from the prior experience and education of board members, the contribution of these directors is limited by their engagement and total workload across all directorships.

Research also shows that director quality can contribute to IPO pricing. Certo (2003) argues that investor perception of board prestige signals legitimacy for the entire organization and improves IPO performance. Bertoni, Meoli, and Vismara (2014) show that boards with value-creation skills are more important to IPO pricing when the company is relatively young; among more mature companies, board monitoring skills are more important to IPO pricing. Similarly, Baum (2017) provides a historical review of the evolution of boards and shows that their monitoring duties, including the independence requirements of public companies, are a relatively late emphasis; boards historically were relied on primarily for advice rather than oversight.

All of this is the 30,000-foot view. Each company faces its own set of managerial, commercial, and competitive challenges, with varying prospects for success. What do actual companies look for in their first outside director, and what does this person contribute to the company and its governance?

The First Director

In fall and winter of 2019, we surveyed 47 private and recently public companies to understand the reasons why they recruited their first outside director. Sample companies include a mix of technology, medical device, biotechnology, energy, real estate, and other service companies. Forty percent of the companies in the sample are publicly traded; the rest are privately held with majority ownership by venture capital (27 percent), private equity (18 percent), or other individual or institutional owners (11 percent). On average, the companies in our sample were founded in 2013 and recruited their first outside director two years later. Those that are public completed their IPO in 2016. Among those that are still private, 36 percent intend to go public, 28 percent do not, and 36 percent are undecided.

Skills and Experiences Requirements

Companies recruit an outside director primarily and clearly to add industry and leadership expertise to the board. The first director is almost always someone with senior-executive level experience within the industry. They are recruited to satisfy a specific advising need, and while governing skill and management oversight are sometimes desired attributes, they are almost never the primary reason for selecting a director.

Eighty-six percent of companies in our sample recruited a director whose primary profession was as an active or retired executive of another company. (These break down as: 36 percent active CEO, 25 percent active senior executive, and 25 percent retired CEO or executive.) By contrast, only 14 percent recruited a first director without executive experience (primarily an unaffiliated investor or other professional director).

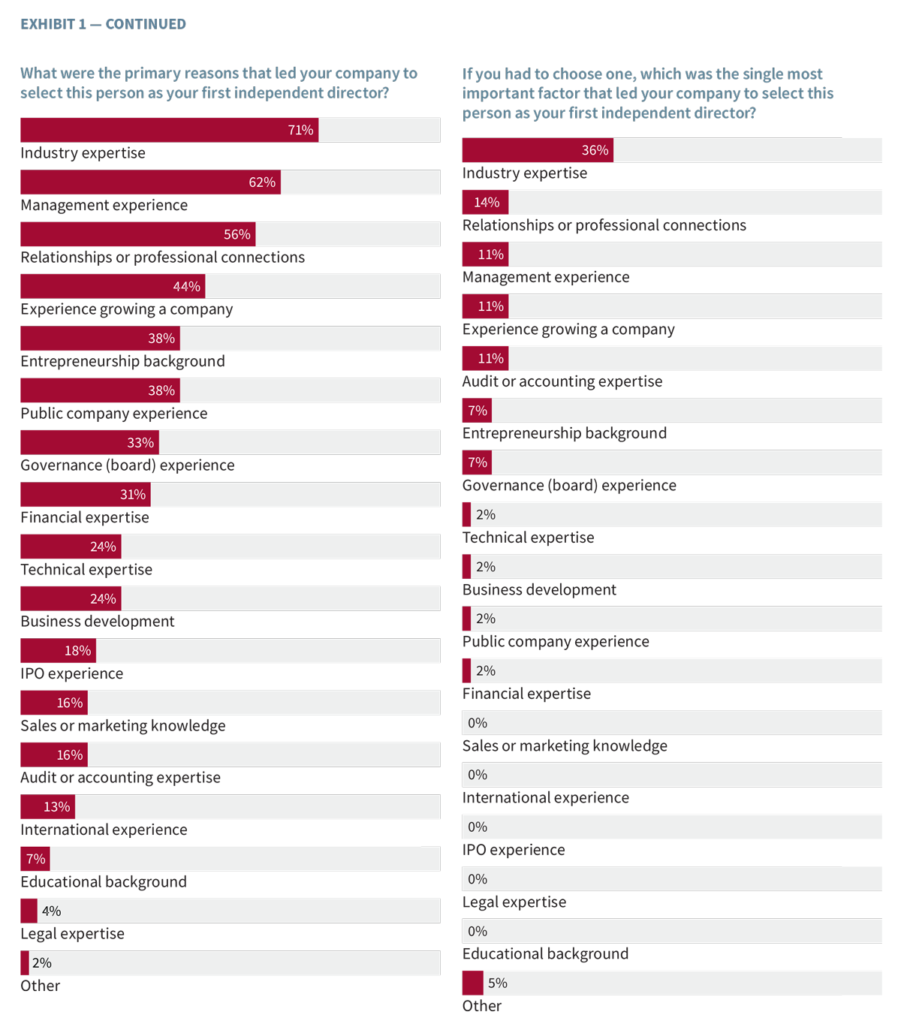

Companies identify a laundry list of reasons for selecting their first outside director. The most frequently cited are industry expertise (71 percent), management experience (62 percent), relationships or professional connections (56 percent), experience growing a company (44 percent), and entrepreneurial background (38 percent). When asked to identify the primary reason for selecting this individual, industry, management, and growth-related reasons are almost always cited. Only 7 percent recruited their first outside director because of his or her prior governance experience (see Exhibit 1).

Source: Proprietary survey of 47 public and private companies conducted in the fall and winter of 2019.

Companies recruit their first outside director to help them address specific pain points they are dealing with. One respondent wanted a director with independent experience to advise management and serve as a counterbalance to the viewpoints of the company’s investors. Another respondent wanted an outsider to provide honest, constructive debate about growth plans and to mentor senior leadership. A third respondent wanted help identifying key trends in the industry and developing metrics for tracking company performance. A fourth respondent needed help bringing product to market. Several companies said they wanted their first outside director to help with talent recruitment, build external partnerships, or position the company for an eventual sale or IPO. Some needed help with internal accounting systems, particularly to ensure future compliance with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

Somewhat surprising, companies do not necessarily look for or highly value prior board experience when recruiting their first outside director. While this is consistent with the statements they make about prioritizing industry growth and managerial issues, it is somewhat surprising that the first outside board member would not necessarily have to be someone with actual board experience. Only 69 percent of first directors had previous experience on another private company board. Just under half (48 percent) had previous public-company board experience. A quarter of first directors did not have any prior board experience or the company did not know if they had this experience (see Exhibit 2).

Source: Proprietary survey of 47 public and private companies conducted in the fall and winter of 2019.

Recruitment Process

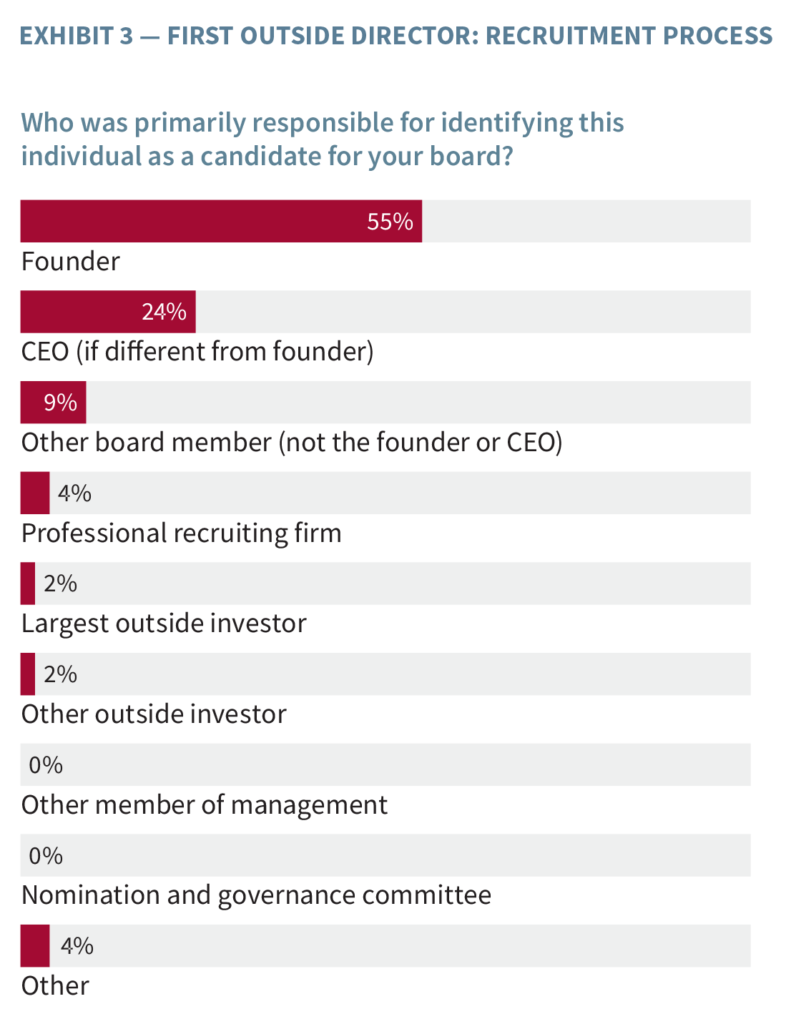

The recruitment process for the first director of a company is quite different from the search process used among more established, public companies. First, the management team is primarily responsible for identifying the first director. This is consistent with the first director serving an advisory rather than oversight role, but something that would be considered a bad governance practice were it to occur in a public company. Over half of the time (55 percent) the founder was responsible for identifying the first outside director; 24 percent of the time it was the CEO (if different from the founder). Board members and investors identify the first recruiter 13 percent of the time. Rarely is a professional recruiter given this responsibility (4 percent).

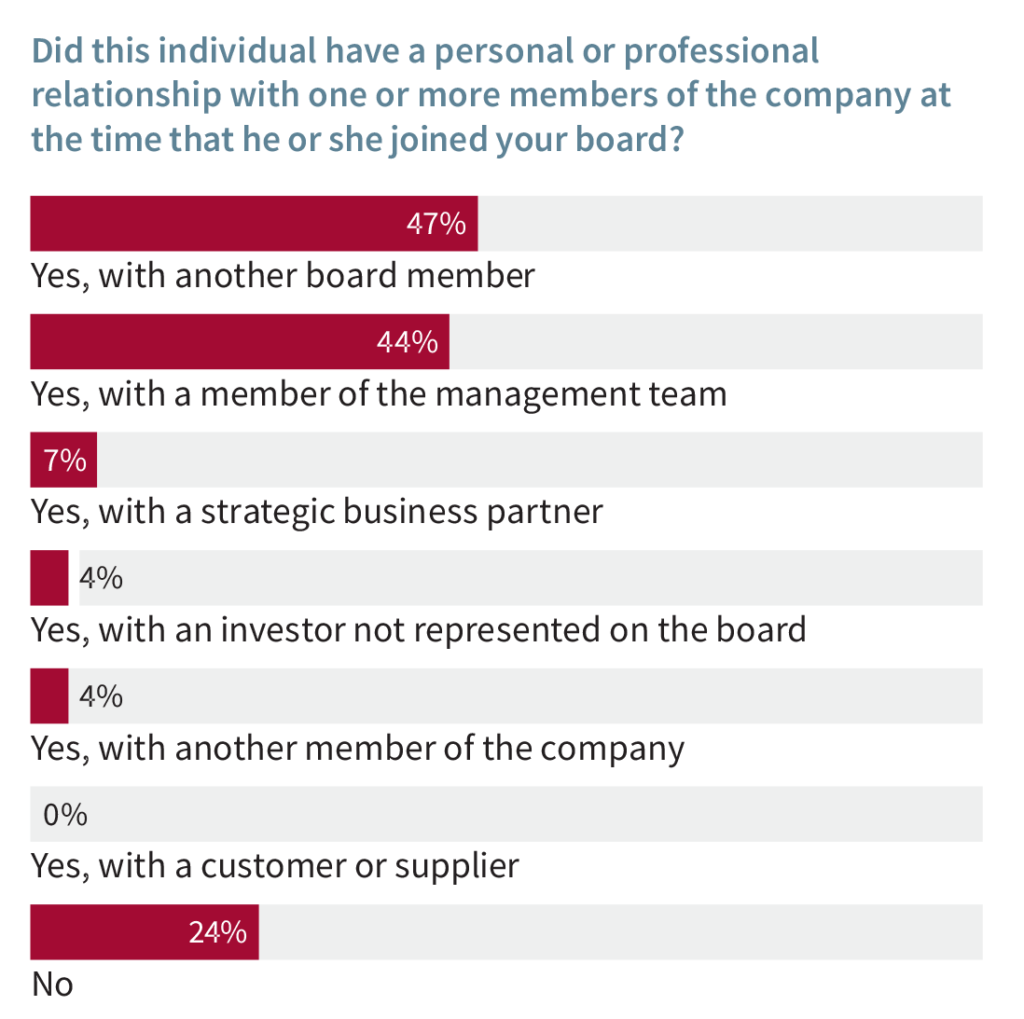

Second, the person selected as the first outside director tends to be personally or professionally connected to insiders at the company. They are less likely to be an unaffiliated, professional director that a public company would recruit. Forty-seven percent of companies said that their first outside director was connected with a board member, and 45 percent with a member of the management team. Others reported that the director was connected to a strategic business partner, an investor not represented on the board, or another member of the company. Only 24 percent of respondents said their first director had no prior connections to the company.

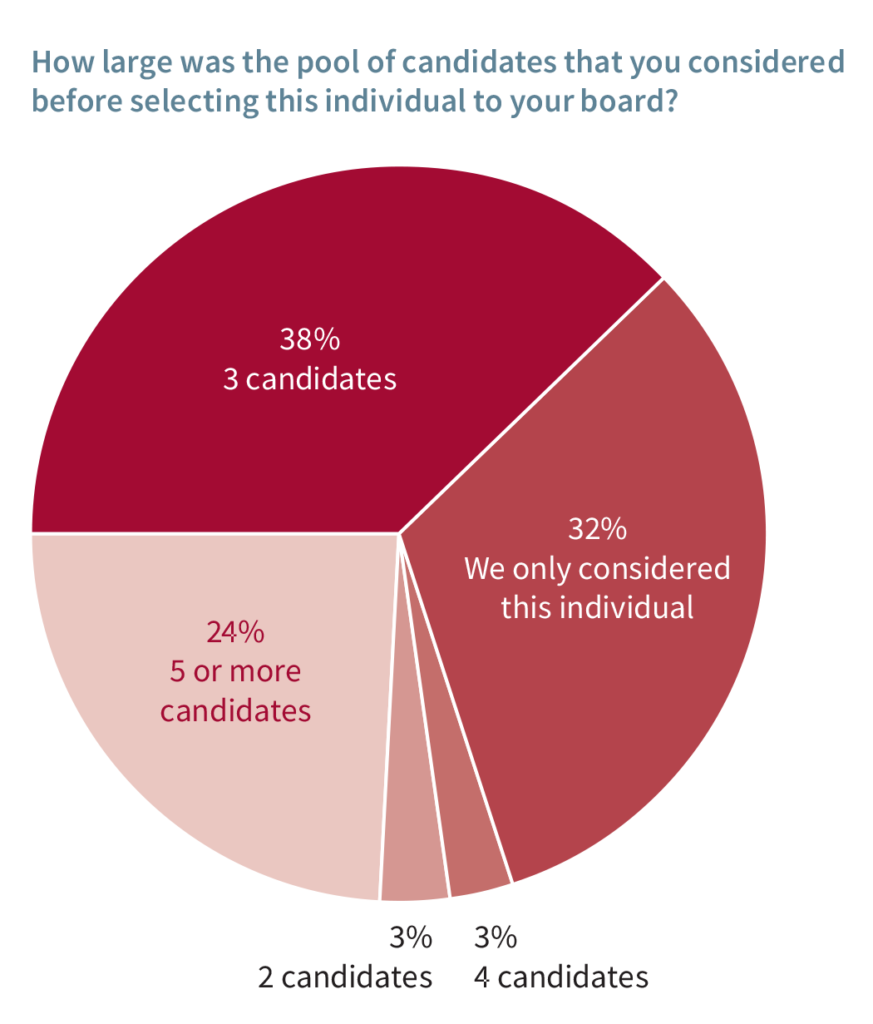

Third, companies consider a very narrow pool of candidates before making their choice of first outside director. A third of the time (32 percent), the company says that they only considered one candidate. Forty-three percent considered between two and four candidates. Only a quarter (24 percent) considered five or more candidates.

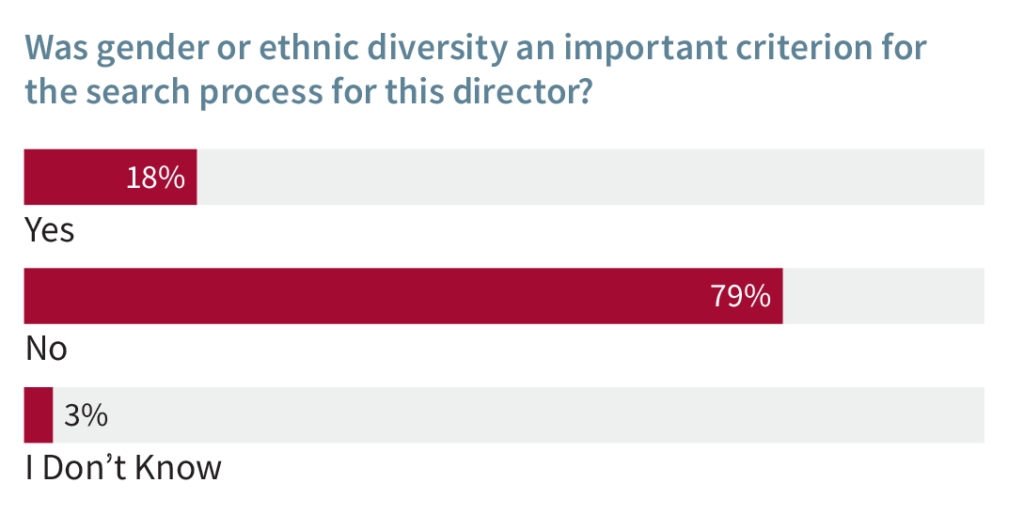

Fourth, unlike among established public companies, diversity is not an important attribute. Only 18 percent of respondents said gender or ethnic diversity were important considerations in selecting their first director. By contrast, gender and ethnic diversity are considered highly important attributes of newly recruited independent directors in large public companies (see Exhibit 3).

Source: Proprietary survey of 47 public and private companies conducted in the fall and winter of 2019.

Source: Proprietary survey of 47 public and private companies conducted in the fall and winter of 2019.

Contribution to Performance and Governance

Companies report that their first outside director makes important contributions to strategy, operations, and governance quality, and this impact is realized in a short period of time.

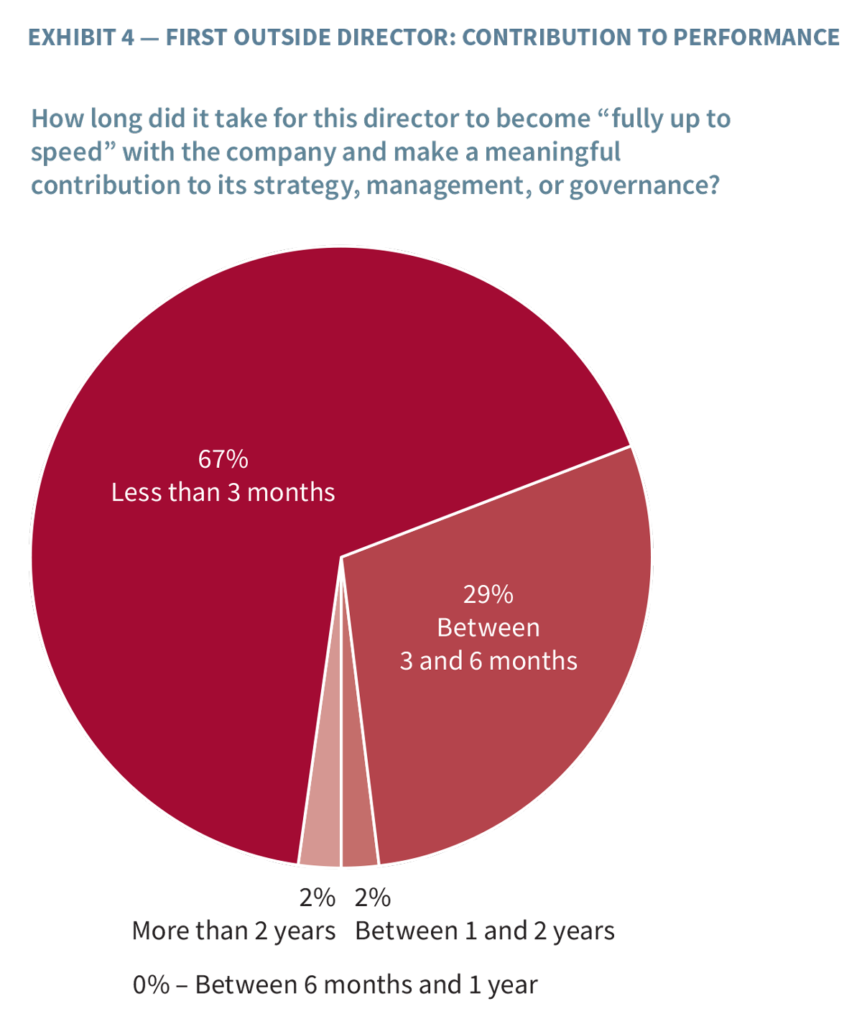

Because of the relative size and simplicity of their businesses, companies report that their first director is able to get fully up to speed in a very short period of time. Two thirds (67 percent) say it took less than 3 months for their first director to get fully up to speed, and 29 percent say it took between 3 and 6 months. A ramp up of this duration would not be possible among large, complex companies, nor would it be possible if the executive did not already have significant industry and managerial experience.

Their first director made his or her most meaningful contributions to strategy (76 percent) and mentoring management (64 percent). Other notable contributions include identifying new customers or business opportunities, bringing products or services to market, formalizing board processes, building up accounting systems and processes, interacting with external stakeholders, preparing for an IPO, and helping to manage legal and regulatory issues. It is interesting to note that, while first directors were not widely expected to contribute to governance oversight when recruited, many of the main contributions that companies cite are to their governance systems and processes.

Specific examples of impact include working with management to develop a more formal growth plan with rigorous, targeted metrics; advising on the timing of growth initiatives; advising on timing for expanding the management team; forcing out underperforming senior managers; and planning the transition to a more experienced CEO to succeed the founder. Some respondents reported improvements in financial reporting quality.

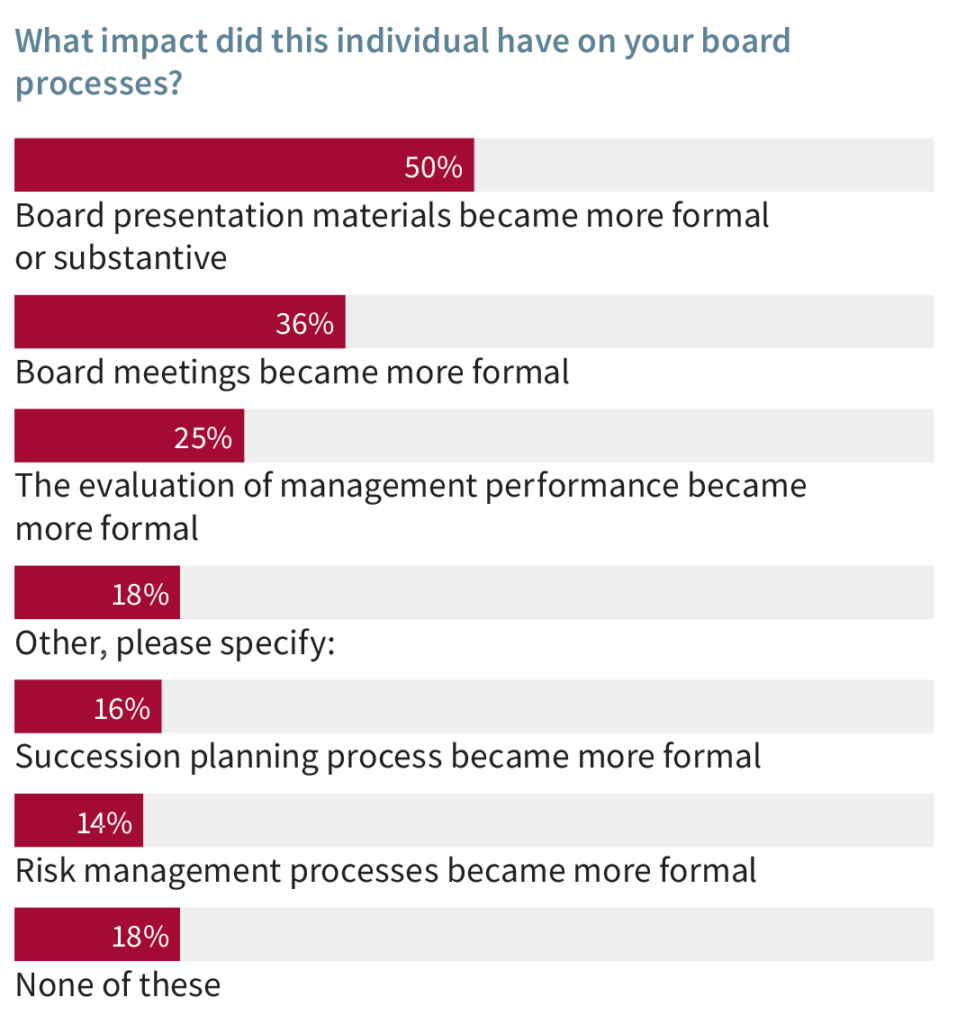

Most companies note that governance processes became more formalized because of their first outside director. Half (50 percent) say board presentation materials became more substantive, a third (36 percent say meetings become more formal, and a quarter (25 percent) say their management performance evaluation process became more rigorous. Other notable contributions include improved succession planning and risk management (see Exhibit 4).

Source: Proprietary survey of 47 public and private companies conducted in the fall and winter of 2019.

Eighty percent of respondents noted that their first outside director is still a member of their board. Among the remaining 20 percent, the first outside director stayed on the board for an average of 3 years. Only one respondent noted that they recruited a director who was the wrong fit, noting that this director was a “smart, good person” but did not have the specific skills the company needed. They noted that removing an underperforming director is a very delicate process.

Why This Matters

- The recruitment process, attributes, and contribution of the first outside director of a pre-IPO company are all very different from those observed among large, publicly traded companies. Considerable attention is paid to the advising contribution of this individual and almost none to their ability to monitor the company in the manner commonly required for public company boards. How does this challenge our view of “good governance”? Are there benefits to having directors who focus less on oversight and more on practical advice—directors with responsibility and real accountability for performance?

- Pre-IPO companies recruit their first director with a specific, targeted business need in mind. These almost always concern strategic, competitive, or organizational dynamics. The individuals recruited to address these challenges are almost always current and former executives with directly relevant experience. Would board quality improve among large, publicly traded companies if greater attention were paid to recruiting directors with this professional profile? Or would board quality suffer because of less diversity of experience and thought?

- The first independent, outside director of a pre-IPO company is not truly independent by the litmus test applied to public company directors. They are almost always someone personally or professionally affiliated with the company, and the founder and CEO often have primary responsibility for identifying them. This approach allows companies to benefit by better assessing director engagement and fit prior to recruitment. However, it dramatically shrinks the pool of qualified candidates and heightens the risk that a director is coopted by insiders and does not provide truly independent oversight. Does a tradeoff exist between engagement and fit on the one hand, and independence on the other? Which is more important to board quality?

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print