David F. Larcker is the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business and Brian Tayan is a Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This post is based on their recent paper.

We recently published a paper on SSRN, Blindsided by Social Risk: How Do Companies Survive a Storm of Their Own Making?, that examines how companies respond to social risk using a proprietary dataset from Marketing Scenario Analytica.

Our concept of risk continues to broaden. Historically, risk managers concerned themselves with strategic, operating, and financial breakdowns that could disrupt business activity and harm shareholder or stakeholder performance. Following the collapse of Enron, risk frameworks broadened to include financial reporting and fraud. Companies developed more rigorous internal control environments to mitigate the likelihood of these events. After the financial crisis of 2008, the scope of risk assessments expanded further, as corporate directors were asked to evaluate how compensation incentives might contribute to risk by rewarding decisions that run counter to or are in excess of the firm’s risk appetite (so-called “excessive risk taking”). Dodd-Frank required expanded analysis and disclosure of the relation between incentives and risk in the annual proxy, and shareholders were given an advisory vote on executive pay (say-on-pay).

More recently, our concept of risk has evolved to include instances in which firm representatives (executives, board members, managers, or general employees) make statements, actions, or decisions that damage the firm by inviting public scrutiny, sparking a reaction among customers, employees, regulators, or the public. This risk is more amorphous than the risks identified above—and harder to plan for. Boards do not know when or where an event might arise; whether it will be triggered by an executive, employee, or customer interaction, or another unexpected catalyst; or the degree to which it will be amplified or distorted through the media. And yet, so called “social risk” can be just as material as any operating, financial, or strategic disruption.

Here, we examine social risk, how it manifests itself, and actions boards and companies might take to mitigate its impact.

Social Risk

Social risk is a loosely defined term that describes events that impair a company’s social capital.(Social capital is the goodwill or positive perception of a company among its stakeholders that contributes economic value through dimensions such as purchase intent by customers, employment attraction or engagement, willingness of suppliers or providers of capital to contract with the firm, etc.) We can distinguish it from other risks in that the primary cause of damage is reputational, whereby an incident harms reputation and, subsequently, performance. In some cases, the risk event involves an interaction with the company’s products or services; in others, it is wholly unrelated to the company’s products and involves actions, decisions, or statements by a company affiliate. Either way, media attention (social or traditional) amplifies the impact, sparking a backlash that extends well beyond the directly affected parties.

For example, in 2017, a passenger was forcibly removed from an overbooked flight on United Airlines. Multiple people on board recorded the man kicking and screaming as he resisted being dragged from the plane by airport agents. The incident became a reputational nightmare for United, which subsequently revised policies to address negative perceptions about its customer service. Even though the direct harm from a customer interaction standpoint was limited, the social damage created by the event was significant.

In another example, in 2017, Papa John’s pizza chain faced a backlash after company founder and spokesman John Schnatter publicly criticized the National Football League’s handling of player protests against the national anthem. Even though the event was unrelated to the sale of pizza, Papa John’s was a sponsor of the NFL, and his comments were received negatively by those who supported the players. Same-store-sales immediately declined, and Schnatter resigned as CEO and was removed from the company’s commercials.

There are a variety of reasons why social risk has intensified in recent years. One is the proliferation of platforms that facilitate the spread of information—news, video, and imagery—in ways not possible even a decade ago. A second reason is heightened sensitivity to issues that might previously have been tolerated or ignored. A third is a growing trend of CEO’s taking public stances on social issues about which they traditionally would have remained silent, sometimes at the instigation of employees or customers wanting to know their position. A fourth is a shift in the public’s view of the purpose of the corporation and a growing sense that corporate actions should be evaluated based on their impact on stakeholders and not solely shareholder value. In this way, the increased prevalence of social risk is coincident with the rise of ESG advocacy.

Research demonstrates the damage that social risk can have on a company’s bottom line. Makridis and Zhou (2018) use Glassdoor reviews to show that corporate misconduct harms the engagement, morale, and productivity of a company’s workforce. The authors find that employee ratings of their firms and managers decline significantly following public announcements of misconduct. Gatzert (2015) finds that events that reflect negatively on a company’s reputation subsequently harm performance. She recommends that firms “place more emphasis on identifying potential reputation risks and invest in mitigation measures … because their financial impact can be severe.”

Research also shows the asymmetric nature of social risk. A 2018 survey by the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University finds that members of the public are more likely to remember corporate stances that they disagree with than those that they agree with, and are more likely to stop using a company’s product because of a position they disagree with than start using one because of a stance they agree with. Robinson, Dirks, and Ozcelik (2004) highlight the bifurcated outcomes of social risk events: in some instances a company’s prior reputation provides a buffer that insulates it from damage (through a reserve of goodwill), while in others it leads to a heightened sense of betrayal that exacerbates damage. Chen, Gainseson, and Liu (2009) show that proactive reputation management strategies can actually increase financial damage by signaling to the market that a problem is worse than it is. The unpredictable nature of social risk underscores the difficulty companies face in anticipating how events resonate among diverse constituents.

Finally, some data suggests that boards are unprepared to manage social risk. One survey finds that reputational risk is the most important area of risk management that boards are concerned about, ranking above operational or regulatory risks such as product risk, succession management, cybersecurity, and fraud. At the same time, a third of boards (32 percent) have few or no plans to address reputational risk.

Social Risk Events

To gain insight into the variety and impact of social risk events, we examine proprietary data from Marketing Scenario Analytica (MSA). MSA advises companies on social risk. As part of their work, they extensively track marketing, operational, and legal situations that damage company reputations. MSA provided us with two samples of data.

Our first sample includes 222 social risk events involving U.S. companies during the month of August 2019 (a month chosen at random to reflect the general level of social risk events). The most notable feature of the sample is the sheer variety of incidents that can introduce social risk. These include corporate policies, employment, and workplace practices that garner public criticism; customer interactions, marketing decisions, and product issues that gain outsized public visibility; or social, environmental, or political issues that ensnare a company—whether or not their actions precipitated their involvement. All of these types of events manifested themselves within just one month’s timeframe. Examples include the following:

Corporate policy, employment, or workplace practices: Google announced a policy of limiting political debate among employees on internal message boards. According to a spokeswoman, “This follows a year of increased incivility on our internal platforms, and we’ve heard that employees want clearer rules of the road on what’s OK to say and what’s not.”

Customer, marketing, or product interactions. Texas-based brewery Manhattan Beer Project Company faced a public backlash for naming a beer after an island where the U.S. government conducted nuclear testing after World War II (Bikini Atoll). According to a critic, “The bottom line is your product makes fun of a horrific situation here in the Marshall Islands … to make money for your company.”

Environmental, social, or political issues. Big data company Palantir was criticized for renewing a $50 million contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) because of that agency’s work in deporting illegal immigrants. Whole Foods employees lobbied parent company Amazon to discontinue all contracts with Palantir because of its work for ICE.

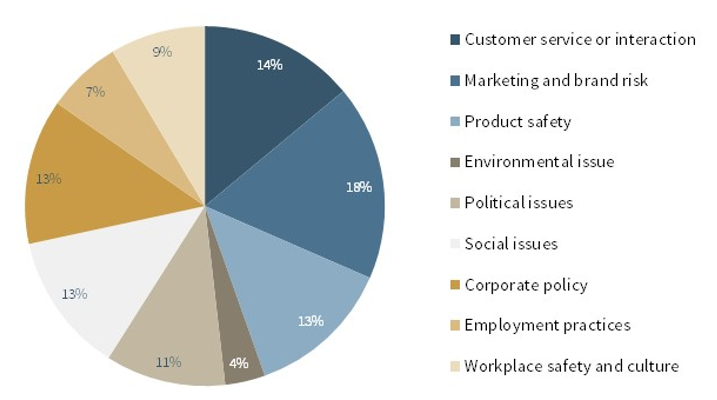

The distribution of social risk events in our sample is fairly evenly distributed across these three broad categories, with 45 percent of events involving customer, marketing, or product interactions; 28 percent involving policy, employment, or workplace practices; and 27 percent involving environmental, social, or political issues (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Social Risk Events

Note: Sample includes 222 risk events in August 2019.

Source: Event data from Marketing Scenario Analytica’s (MSA) Risk Event Database; research by the authors.

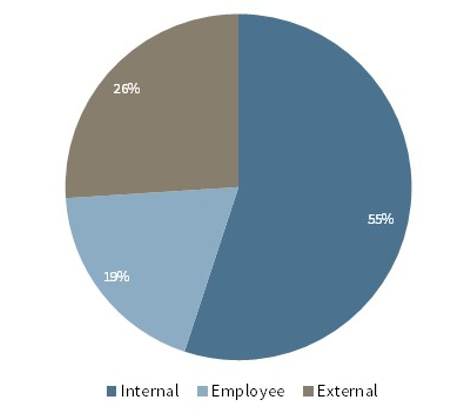

The catalyst that initiated the social risk events in our sample more frequently involved internal corporate decisions or employee actions, and less frequently external catalysts. Just over half (55 percent) of the risk events in our sample were initiated by a corporate policy, product, or branding decision or other action taken by a company representative; an additional 19 percent involved employee protests or employment-related issues that gained public attention. By contrast, 26 percent of events were the result of external scrutiny that the company did not invite through deliberate actions or choices (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Catalysts That Precipitate Social Risks

Note: Internal catalysts includes corporate policies, product, or branding decisions.

Source: Event data from Marketing Scenario Analytica’s (MSA) Risk Event Database; research by the authors.

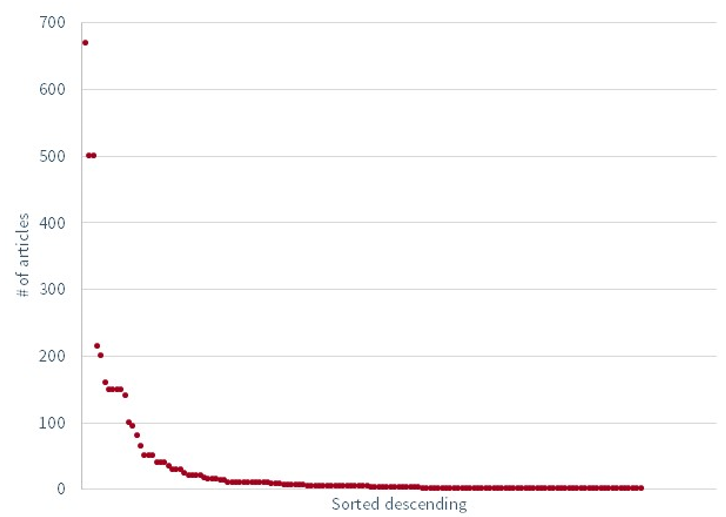

Media coverage of these events is significantly skewed, with most events the subject of only a handful of articles or references, and a handful of events the subject of hundreds of articles. Consistent with this, most events have a very short shelf life, disappearing from print after a few days or weeks, while a small number remain in the media spotlight for months (see Exhibit 3). For example, a public feud between CVS and Pill Club over the rates charged for birth control pills was mostly forgotten after a few days, while reports that Apple’s digital assistant software Siri recorded personal conversations and could be accessed by contract workers was cited in hundreds of articles months after it was first reported.

Exhibit 3: Media Coverage of Social Risk Events over Subsequent 9 Months

Note: Captured as number of articles referencing the event between August 2019 and May 2020.

Source: Event data from Marketing Scenario Analytica’s (MSA) Risk Event Database; article counts based on Factiva searches by the authors.

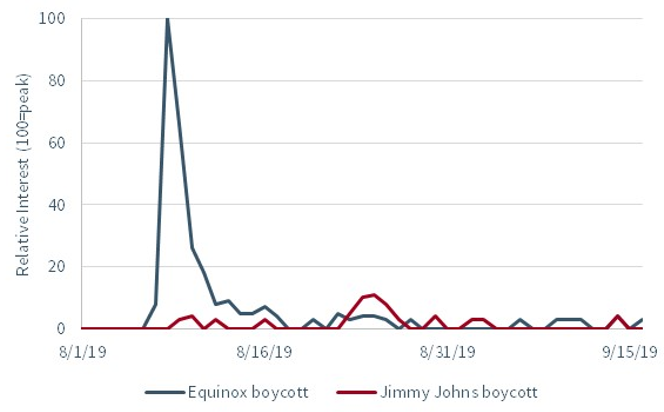

This pattern of asymmetrical impact also manifests itself in social media. For example, data from Google Trends shows the disproportionate impact of fairly similar risk events: one, a boycott of fitness company Equinox because of a political fundraiser hosted by the company’s chairman; and two, a boycott of restaurant chain Jimmy John’s because of photos posted of the company chairman hunting endangered elephants. The Equinox boycott received over 10 times the interest on social media than the Jimmy John’s incident (see Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: Google Trends: A Comparison of Two Boycotts

Source: Event data from Marketing Scenario Analytica’s (MSA) Risk Event Database; Google Trends analysis by the authors.

Another feature of social risk events is that, once significant ones occur, they frequently reemerge in some new way to further damage the company’s reputation. They also transfer across companies as public attention looks for analogous occurrences at unrelated firms. For example, allegations of employee harassment encourage deeper scrutiny of other workplace practices at the firm or across firms, and one company’s public stance on a societal issue invites inquiry into the stance of peer organizations on the same issue. A third of events (36 percent) in our sample can be categorized as these types of repeat events.

The tangible impact of social risk events on corporate performance is less clear. We find an average (median) market-adjusted decline in stock price of 0.4 percent (0.4 percent) over the 3-day period surrounding the first article mentioning the issue. Often, the company issues a public statement (55 percent). Less frequently does the board launch an investigation (9 percent) or is a senior executive or manager terminated (15 percent). In only a minority of cases did the event lead to formal lawsuits, regulatory scrutiny, or trigger SEC disclosure. These almost exclusively involved higher profile social risk events impacting prominent corporations, such as Alphabet, Capital One, Uber, or Wal-Mart.

Race-Related Social Risk Events

We also analyzed a second sample of MSA social risk events involving corporations caught up in the national debate on race following the death of George Floyd. This sample includes 143 incidents between May 25 and June 25, 2020.

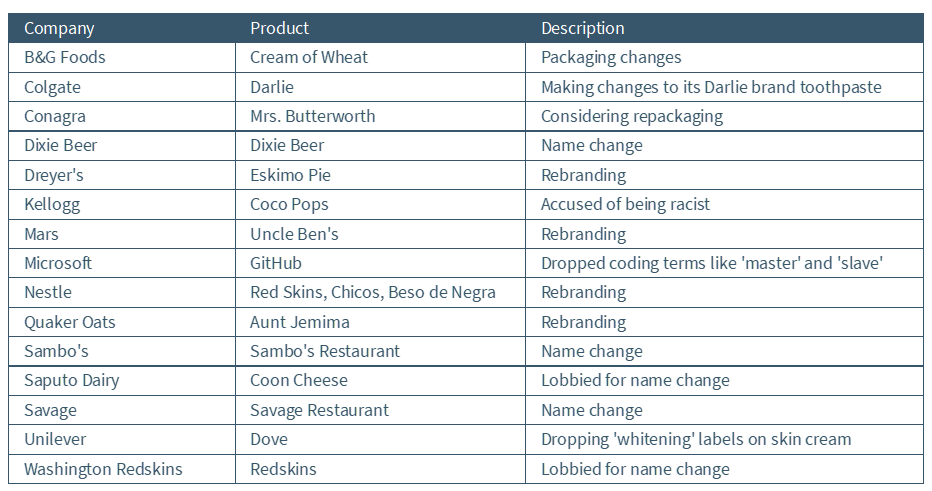

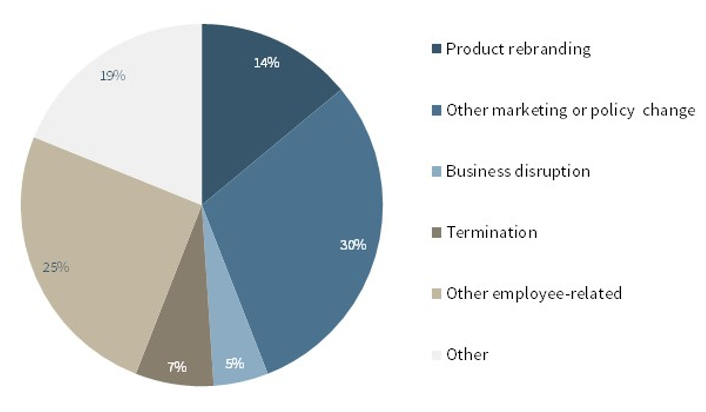

Despite being focused on a single issue, these race-related social risk events are also remarkable for their diversity. They involve product branding decisions (14 percent), marketing or other policy changes (30 percent), business disruption or cancellations (5 percent), employee terminations (7 percent), employee-related initiatives or protests (25 percent), and other issues, initiatives, or boycotts involving a company (19 percent). See Exhibit 5.

Exhibit 5: Selected Product Rebranding Decisions (Proposed or Actual)

Source: Event data from Marketing Scenario Analytica’s (MSA) Risk Event Database; research by the authors.

The media coverage of corporate involvement in race-related issues during this period is predominantly negative in tone. Three-quarters involve allegations of racism, forced changes to products or policies deemed racist or discriminatory, or terminations for allegedly racist behavior or for condoning racism. By contrast, only a quarter of coverage emphasizes positive policies to promote equality or awareness, or donations or investments to promote positive outcomes. Of note, the vast majority of these positive actions took place in the second half of the measurement period, indicating that most companies were somewhat slow to respond to events as they unfolded.

Finally, it is remarkable how many companies, in a very short time frame, made changes to or actively considered changing the names of products whose brands in some cases extended back for over a century. This surprising outcome underscores the severity of social risk (see Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: Race-Related Social Risk Events

Note: Sample includes 143 race-related social risk events between May 25 and June 25, 2020.

Source: Event data from Marketing Scenario Analytica’s (MSA) Risk Event Database; research by the authors.

Recommendations

In order for boards and CEOs to prepare for, manage, and mitigate social risk, MSA recommends the following:

- Use knowledge of the past to inform future plans. Companies can accomplish this by examining social risk events that have impacted peer groups and related industries. By developing a comprehensive history of social risk, managements and boards can understand the variety of potential risks it faces and evaluate patterns in how risk events have evolved over time.

- Conduct scenario planning to identify the highest likelihood risk events. This involves identifying events that are most likely to manifest themselves based on the company’s industry, profile, and vulnerabilities. Quantify the severity by looking at the potential impact on brand, product, suppliers, employees, and overall reputation.

- Prepare responses and identify the resources necessary to prevent or mitigate the highest likelihood risks. Consider both preventative and responsive measures, over both short-term and long-term time horizons, and develop resources, programs, and policies to protect the company on an ongoing bases.

Why This Matters

- Companies face an array of social risks brought about by branding, product, or policy decisions, or by employee or customer interactions, many of which are outside the company’s control or difficult to predict. How can companies prepare for and mitigate social risk? Given the sheer diversity of risks, how can boards of directors prioritize their focus?

- Social risk appears to inflict unpredictable damage on corporations and their brands. A risk event at one company might gain widespread attention and attach itself permanently to a brand, while a similar event at another company might pass by with little impact. How can a company gauge at the onset whether a social risk will be major or minor? What actions can senior officers take to mitigate the life of the risk?

- Many social risk items appear immaterial from a financial standpoint and because they lack definition are difficult to capture, track, and plan for under standard risk management frameworks. How can social risk be incorporated into risk management programs? What roles do management, audit, legal, and human resources play in this process? Is mentioning social risk as a “risk factor” in the Form 10-K sufficient?

- Many social risk events have a cultural or leadership component. How can boards evaluate the quality of the company’s culture and leadership to determine how they influence the risk profile of the company? What actions should boards take if culture and leadership are deemed to increase risk?

The complete paper is available here.

Print

Print