John Borneman is Managing Director, Tatyana Day is Senior Consultant, and Olivia Voorhis is a Consultant at Semler Brossy. This post is based on a Semler Brossy report by Mr. Borneman, Ms. Day, Ms. Voorhis, and Kevin Masini. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); and Paying for Long-Term Performance by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried (discussed on the Forum here).

Shareholders have increasingly highlighted the importance of measures of social and environmental sustainability as a key component of ESG. The COVID-19 crisis and growing focus on racial inequities will only accelerate the demand for companies to expand their definition of social responsibility to include the broader societal impact of the corporation.

In recent years, debates over the role of the corporation in society have become more prominent, with corporations increasingly seen as responsible towards a broad group of stakeholders. Though some critics have argued that these debates don’t portend a fundamental departure from how businesses currently operate, there does seem to be a true shift in shareholder demands. Pushing for responsibility to a wider range of stakeholders is an attempt to encapsulate and operationalize these demands, with a growing emphasis on the long-term social and environmental sustainability of the corporate model.

As part of, and in response to, these demands are growing calls for increased transparency and standardization of companies tracking and disclosing ESG progress. The “Big Four” accounting firms, for example, are partnering with the World Economic Forum International Business Council to set standards for disclosure on ESG issues, with the intention of identifying common, verifiable ESG metrics for all companies to report on. Third-party ESG rating systems are gaining prominence as sustainability-linked loans and ESG investing gather momentum. The SEC’s Investor Advisory Committee has also recommended the SEC require standardized ESG disclosures. Environmental and social sustainability metrics are key pillars of many of these disclosure initiatives.

As measures of progress become more widespread, standardized, and scrutinized, we expect ESG metrics to become integrated more often—and more firmly—into compensation plans, with a growing emphasis on sustainability issues.

“As CEOs, we want to create long-term value to shareholders by delivering solid returns for shareholders AND by operating a sustainable business model that addresses the long-term goals of society”

—Brian Moynihan Chairman and CEO, Bank of America, and Chairman, International Business Council of the World Economic Forum

Sustainability vs. Operational Metrics

In our last report we shared the finding that 62% of companies in the Fortune 200 incorporate stakeholder metrics—ESG measures—in their executive compensation programs. However, the influence these metrics have on pay outcomes can differ drastically, with many companies using a largely discretionary assessment to determine payouts.

In this post, we look beyond the prominence of ESG and delve into the specific types of metrics being used. In particular, we note that while many measures of “stakeholder interests” are often categorized as “ESG”, most of these measures do not explicitly relate to progress toward the longer-term, broad environmental and social sustainability objectives that are at the center of recent shareholder demands.

For the purpose of this post we have allocated ESG metrics into two broad groups:

| Sustainability ESG Metrics

Measures concerned with longer-term, broad social/economic stability |

Operational ESG Metrics

Other stakeholder metrics that are more aligned with day-to-day business results |

|---|---|

|

|

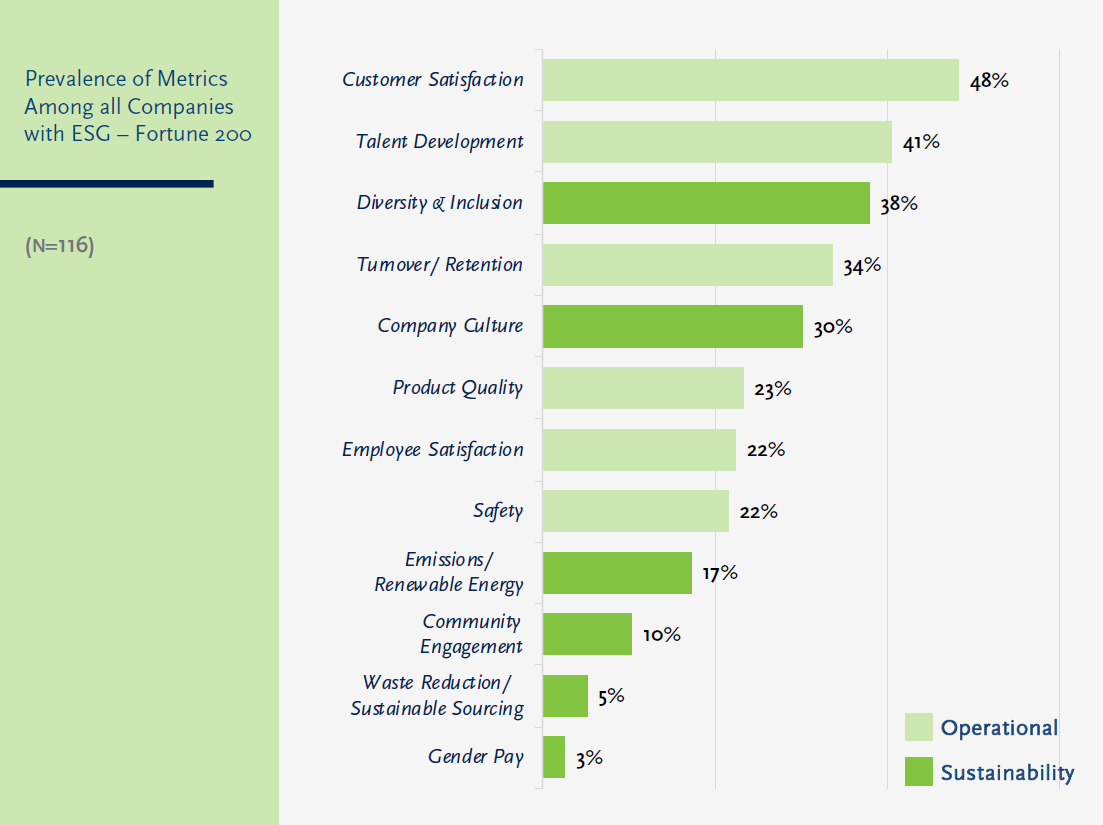

The most common ESG metric overall is customer satisfaction, with 48% of companies that use ESG metrics including it in their plans. The next four most prevalent involve measures of workforce-management and culture:

- Talent development and turnover are the most prevalent “Operational ESG” metrics overall, though are often incorporated discretionarily

- Diversity & inclusion is the most prevalent “Sustainability ESG” metric, followed by culture

Other sustainability ESG metrics, including environment, are low prevalence.

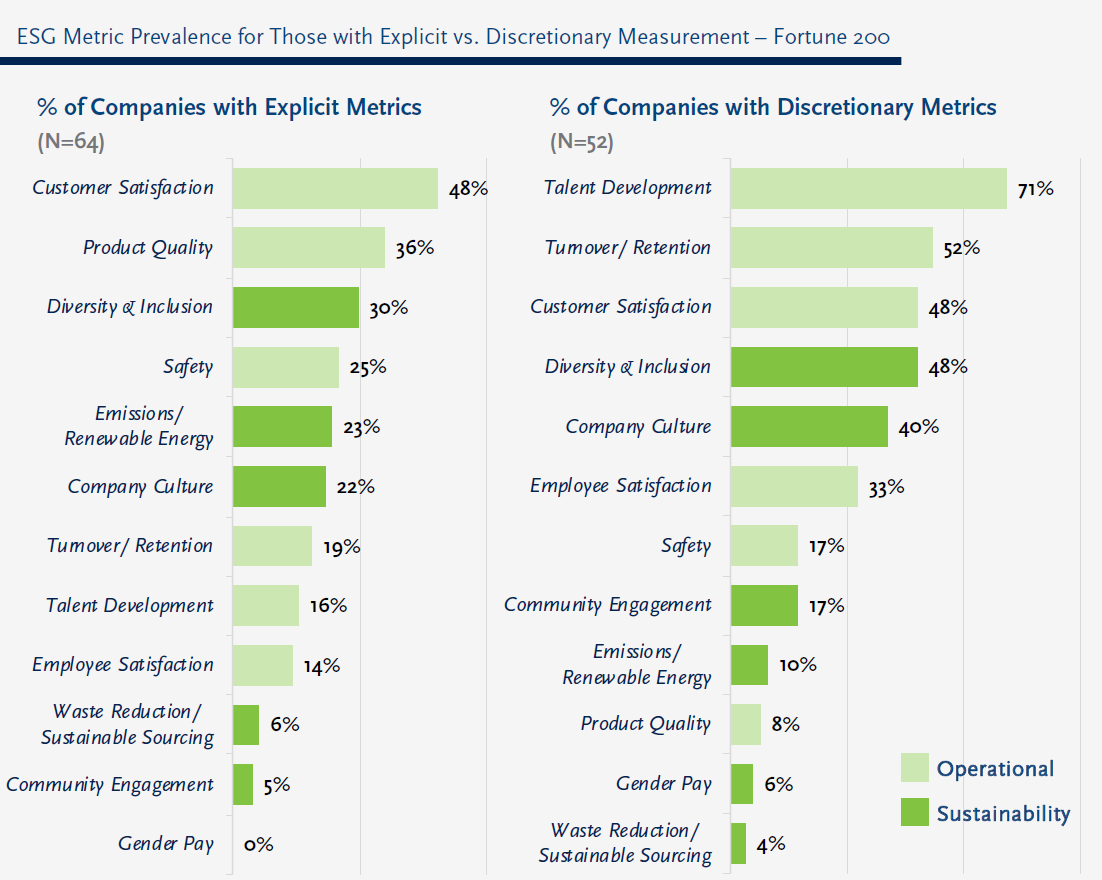

We uncover additional trends when we break down these measures further by those companies that explicitly measure ESG using a carve out for performance vs. those that use a more discretionary, individual assessment. For companies with explicit weightings (at left below), the most prevalent metrics are related to customer satisfaction and product quality as classic measures of “good business.” Talent management-focused metrics (talent development, turnover) are more commonly assessed in a more discretionary framework (at right below). Notably, diversity & inclusion is still one of the most prevalent metrics regardless of whether it is used explicitly or as part of a discretionary framework.

Not surprisingly, ESG related measures tend to be more prominent in pay plans when they can be easily quantified and have a more clear-cut impact on the top- or bottom-line. Hence measures like product quality, customer satisfaction, and workplace safety often have explicit weightings and a direct impact on incentive pay.

Likewise, measures related to environmental sustainability are often easier to quantify and assess rigorously, making it possible to formally integrate more environmental metrics into incentive plans. Indeed, when present, climate-related goals are more often integrated on a more explicit basis in incentive plans. However, the prevalence of environmental sustainability metrics is still relatively low, which is somewhat surprising given external pressure to make progress on environmental sustainability and climate change.

Over the past few years, “people” metrics have come to the fore and these show up with high frequency in incentive plan designs. But objectives related to people management tend to be “softer” metrics and subject to more judgement and nuance to accurately assess performance. As a result, performance related to talent development, turnover, company culture, etc., are often assessed as a discretionary element of incentives, and often along with a broader scorecard of business and strategic considerations.

Diversity & Inclusion (D&I) Metrics

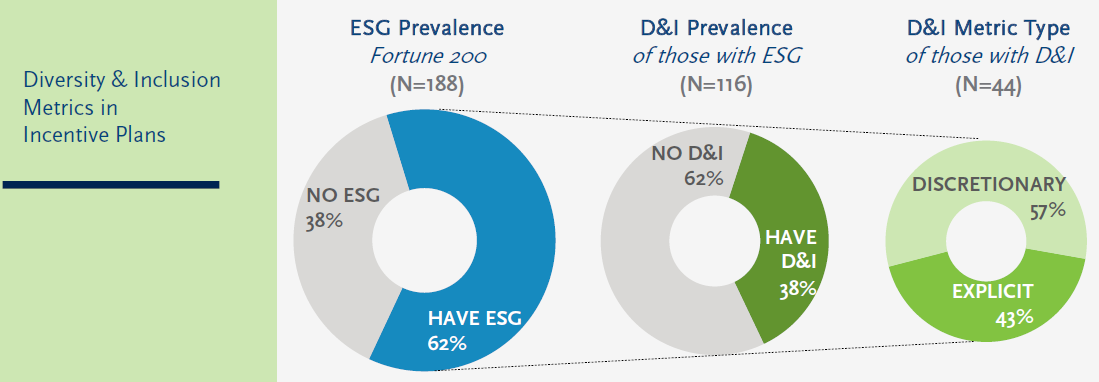

The most prevalent sustainability ESG metric currently incorporated in executive incentives is diversity & inclusion. It is the third most prevalent ESG metric in the sample both overall and when measured on a purely explicit basis.

D&I’s relatively high prevalence is partially related to the growing incorporation of talent-related metrics in executive incentives overall: this measure has both a “talent” angle and a “social responsibility” angle.

Of companies with ESG measures, 38% use a D&I metric (or 23% of all companies in the sample). However, well over half of companies with D&I include it on a discretionary basis. Despite seeming prevalence, only 10% of all companies in the overall sample include a D&I metric with a formal weighting in executive incentives.

This trend speaks to many Boards’ traditional hesitation to set and disclose formal targets around D&I initiatives, likely due both to general discomfort around setting “quotas” and optics as well as risks associated with disclosing performance that may be subject to external criticism. In addition, many companies recognize that “hard” metrics of representation in an employee population do not capture the cultural aspect of a truly inclusive organization—measuring “Diversity” results without assessing “Inclusion” is an incomplete answer. A more balanced assessment may require discretion and judgement.

Demands for more accountability around companies’ D&I progress are likely to be accelerated by recent public outcry over racial justice issues. D&I prevalence and explicit measurement in incentive plans will likely increase as a result, although we anticipate continued debates over the merits of incentivizing representation statistics as the primary measurement approach.

Conclusion

While broad prevalence statistics indicate that ESG metrics are currently widespread in executive incentives, many of these are measures of direct stakeholder impact tied to day-to-day business operations, rather than the broad, long-term sustainability objectives increasingly advocated by both shareholders and third-party institutions. However, as more companies look to integrate environmental and social impact objectives into their incentives, existing examples will prove a crucial starting point for design.

Print

Print