Kira Medish is a Summer Business Analyst, Tracy Branding Pyle is a Director, and James Bamford is a Managing Director at Water Street Partners, an Ankura Company. This post is based on their Water Street memorandum.

When Honeywell restructured its highly-successful joint venture in Japan with Yamatake in 1990, the dealmakers included vaguely-defined scope and exclusivity terms—a decision that ultimately contributed to the end of the 40-year partnership. These terms allowed both Honeywell and the JV to compete in “Other Asia,” a geographic market which included China; the parties felt their history and senior-level ties meant any issues would be quickly resolved. Yet as the business grew and markets globalized, Honeywell and the JV found themselves in repeated head-to-head competition, and personal relationships were no match for potential profits. With customers caught in the crossfire and competitors growing stronger, the partners debated for years over structuring a solution that should have been negotiated at the outset, and the relationship never fully recovered; Yamatake ultimately bought out Honeywell in 2002. [1] [2]

Or consider a media joint venture in India between an international conglomerate and a local partner. In this case, the international partner assigned exclusive use of its brands and the right to market all its products in the country to the JV. When the JV seriously underperformed, the international partner had no choice but to negotiate an expensive buyout of the local partner to regain its ability to compete in a key global market.

Such predicaments may seem like rare errors of strategic thinking and contract drafting. But our recent benchmarking study of 40 JV agreements shows that non-competition and exclusivity terms tend to lack adequate elasticity and contingency provisions in defining the activities the JV and each parent can and cannot do. In our experience, rigid joint venture agreements can lead to otherwise avoidable conflicts between the JV and one or more parents, and thus to suboptimal performance or even failure of the venture. Conversely, smart JV agreements anticipate an array of changed circumstances and other business contingencies and provide a least a degree of elasticity or future-proofing in the exclusivity and non-competes. [3]

To help companies understand how to structure exclusivity and non-competition provisions in joint venture agreements, we recently reviewed the legal agreements of 40 large joint ventures. The ventures in our dataset were drawn from across industries and geographies and involved three types of ventures: technology commercialization JVs, market entry JVs, and consolidation JVs. All JVs in our analysis were incorporated business entities. Below, we explore the prevalence and contours of exclusivity and non-competition provisions in JV agreements [4], share examples of how parties have planned such provisions to automatically adjust in the event that JV or parent circumstances change in the future, and offer advice to dealmakers on how to improve JV agreement durability by thinking more fulsomely about future evolution and designing a JV agreement with the flexibility to function in a constantly evolving world.

Exclusivity and Non-Compete Provisions

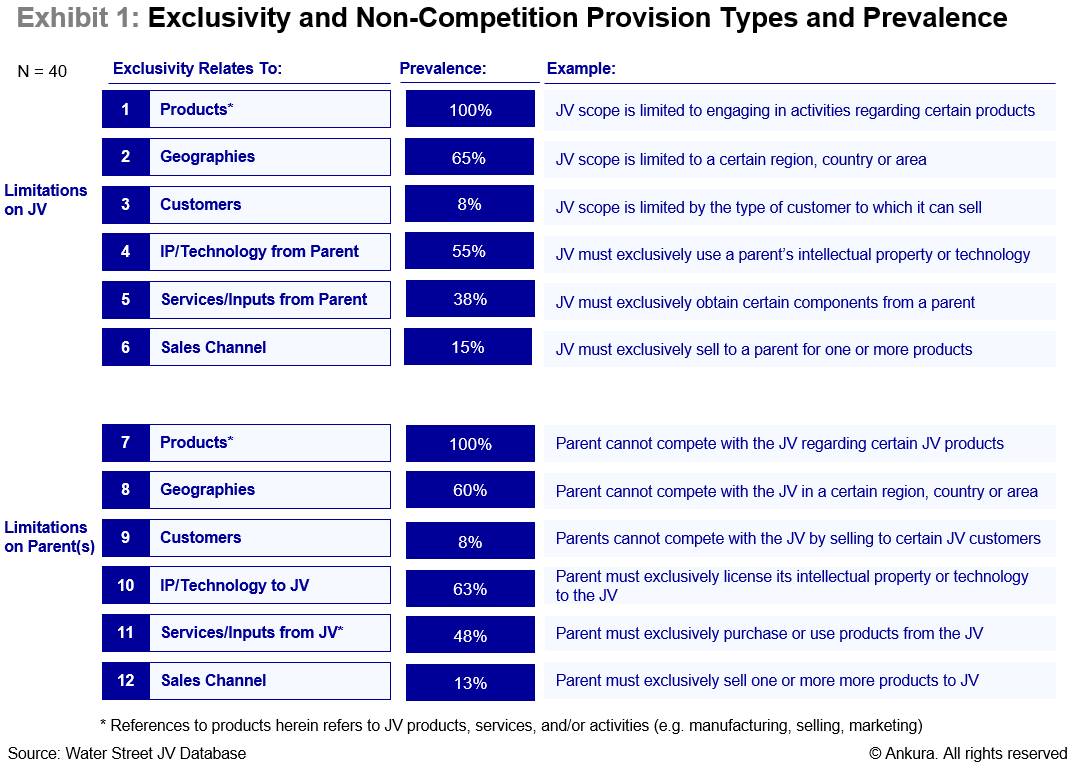

Types and General Prevalence. Joint venture exclusivity and non-competition provisions come in many forms, and are often housed in different contractual agreements and provisions. Such contractual terms may impose requirements or limitations on either the venture or a parent with regard to geographic scope, product or service scope, customers, sales channels, use of technology or intellectual property, or services and other supply (Exhibit 1). [5]

Our analysis shows that product and geographic limitations are by far the most prevalent types of exclusivity in joint ventures, with 70% of agreements including both these types of limitations. Terms limiting freedoms to sell to specific groups of customers were least common in our dataset, present in only 8% of agreements.

An important note is that certain non-competition arrangements may be prohibited by antitrust laws, which vary by jurisdiction but generally allow some contractual prohibitions on competition in joint venture agreements if the pro-competitive benefits of such an arrangement outweigh anti-competitive effects. JV partners should consult antitrust counsel prior to entering into any exclusive arrangements, and, in particular, should be wary when allocating geographic markets or customers.

Parties mix and match different forms of non-competition and exclusivity to create fit-for-purpose boundaries for a JV and its parents. Because exclusivity provisions are tied to the particular context, certain types of exclusivity are more prevalent in JVs in different industries or venture types. For example, only 36% of downstream oil and gas, chemicals, and agriculture ventures include limitations on both the parents and the JV regarding geography—a prevalence significantly lower than JVs in other industries. One reason for this discrepancy is that such JVs often consist of large facilities located near natural resources and require large capital expenditures (and partner approval) to expand elsewhere and thus geographic limitations are implicit even if not defined by the JV’s scope or limitations on where partners can do business. By contrast, 70% of JVs to develop and commercialize technology included exclusivity or non-competition limitations on one or more parent companies related to intellectual property—a figure which is substantially higher than for consolidation JVs, for instance.

Exclusivity provisions also vary in terms of their level of complexity. In certain joint ventures, such as MillerCoors—a multi-billion-dollar JV that consolidated the U.S. beer operations of SAB Miller and Molson Coors beginning in 2008– the exclusivity regime was straightforward. The JV exclusively did business related to beer and beverages in the U.S. and Puerto Rico and the parents could not compete with the JV in those geographic markets. Indeed, it is quite common to see language in JV agreements stating something to the effect of “the parties shall engage in the JV Business (whether directly or indirectly through affiliates or collaborations with third parties) exclusively through the JV Company.”

It gets more complex when mixing and matching geographies, describing who acts where instead of stating that one or more parents cannot compete with the JV. Consider Kirin-Amgen, a highly successful 50:50 joint venture formed in 1984 between Kirin and biotechnology pioneer Amgen to produce and sell erythropoietin (EPO), a genetically-engineered biochemical for human therapeutics. In this case, the parties defined the geographic boundaries of the venture as the whole world except Japan and the U.S., the home countries of Kirin and Amgen, respectively—where both companies already had business they could continue. In addition, both parents were subject to non-competes within the EPO market up to 20 years after the closing date.

Most complex is when provisions include a combination of exclusivity and competition. For example, in a global joint venture to develop, manufacture, and sell soy-based ingredients and soy polymers, the parents were not allowed to conduct business within the JV scope except in certain countries, where one partner was allowed to manufacture and sell a subset of the JV products within Germany, Spain, Hungary, and Austria (which were also within the JV’s geographic scope and thus a source of competition).

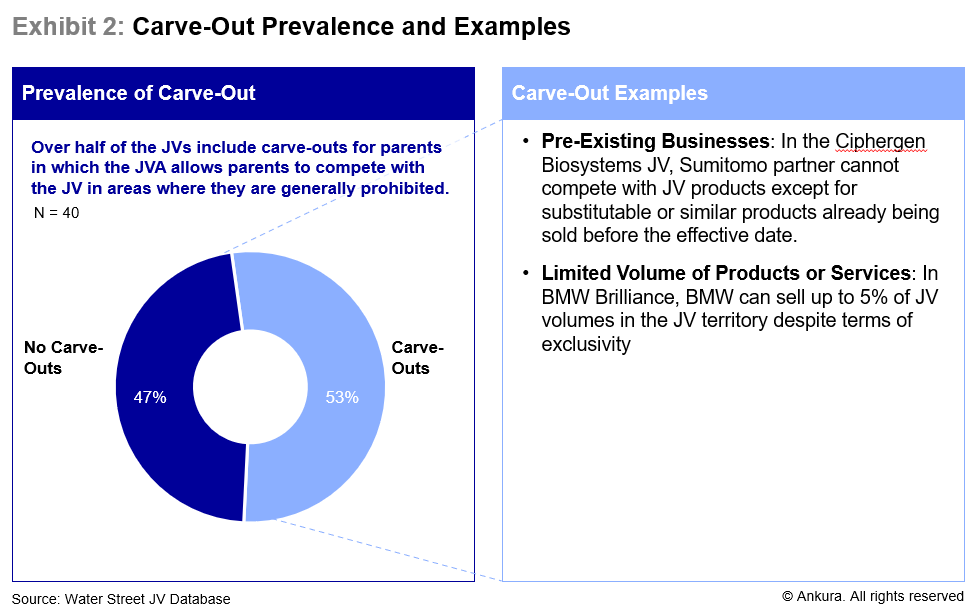

Parent Company Exclusivity Carve-Outs. Going further, our analysis shows that 53% of agreements establish certain “exclusivity carve-outs” for the parents—that is, terms that allow one or more parent to compete in the JV’s market under certain circumstances (Exhibit 2).

Typically, such terms are derived from the unique starting context of the venture, and come in one of the following forms:

- Pre–Existing Parent Businesses (e.g., a parent can compete with JV for products parent sells on the effective date);

- Pre-Defined Period (e.g., a parent can compete with the JV for the first two years following JV formation);

- Limited Volume of Products or Services (e.g., a parent can sell its own products in the JV territory provided that such volumes do not exceed 5% of the JVs sales).

For example, in the JV agreement for Ciphergen Biosystems, a JV between Sumitomo and Ciphergen to develop and market biosystems for protein discovery and other protein-related R&D, both parents were prohibited from competing within the JV business. However, although Sumitomo was prohibited from competing with JV products, it was exempt from that provision with regard to substitutable or similar products already being sold before the effective date. This carve-out allowed Sumitomo to compete with the JV in a narrow set of circumstances with clearly-defined limitations.

Carve-outs tend to be more prevalent in JVs in certain industries. For example, 64% of the downstream, chemicals, and agriculture JVs we reviewed included carve-outs while only 40% of high technology JVs did. This discrepancy may, in part, be due to the fact that many downstream, chemical and agriculture companies use similar, if not the same, processes to develop products across a range of ventures or subsidiaries which makes carve-outs particularly attractive as they allow companies to “carve up” the world and continue performing a subset of operations across ventures. Whereas companies in the high technology industry, which entails expensive R&D, are less likely to invest in multiple, competing technologies.

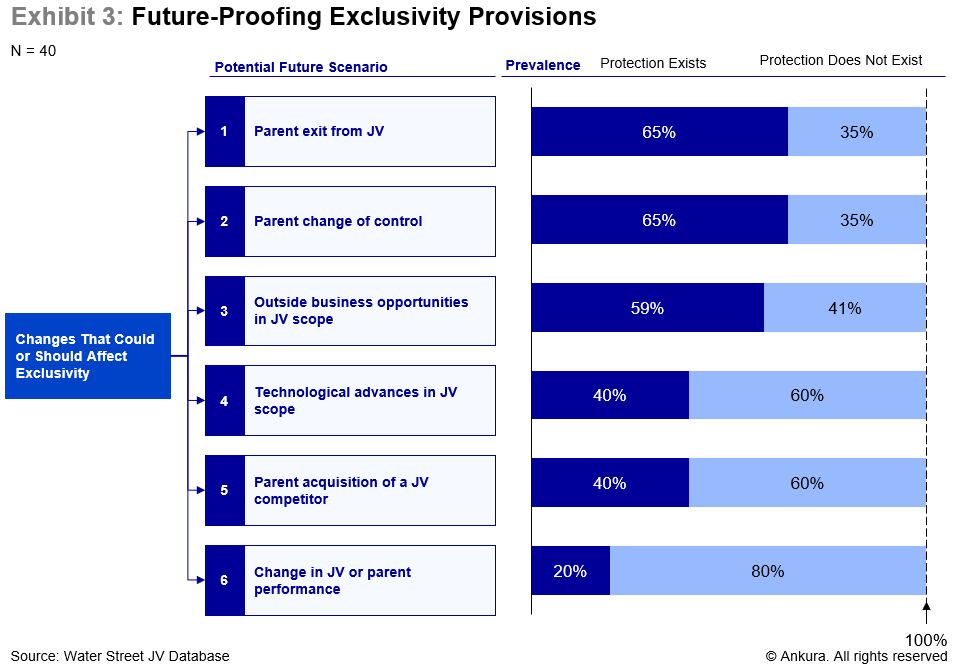

Future Flexibility in Exclusivity Provisions. In our benchmarking of JV agreements, we also looked at whether joint venture agreements sought to “future proof” their exclusivity and non-competition terms by contemplating changes to the arrangements upon the occurrence of six types of potential future events.

These events were:

- Parent Exit from JV: What effect, if any, will a parent’s exit from a joint venture have on exclusivity provisions? For example, will the exiting partner be prohibited from competing with the JV for any period of time or do any exclusivity arrangements with the exiting partner terminate upon exit?

- Parent Change of Control: What occurs if a parent is acquired by third party that may or may not be a competitor of the JV or the other venture partner(s)? Would this give either parent the right to exit the JV or to terminate exclusivity?

- Outside Business Opportunities: Are there obligations or exceptions to exclusivity regarding business opportunities within the JV’s scope? For instance, would a parent need to offer a business opportunity (e.g., investment, partnership, acquisition) to the JV if that opportunity is in the venture’s scope? Are parents allowed to pursue certain types of investments within the JV’s exclusive scope either outright or if the JV turns down the opportunity?

- Technological Advances: When technological advances occur within or adjacent to the JV’s authorized scope, how will those changes be reflected in non-compete and exclusivity provisions?

- Parent Acquires a Competitor: Will the JV have the option to acquire competing assets or businesses which were acquired in a broader acquisition of a parent company? If so, what will be the ramifications be on JV terms?

- Poor Performance: If the venture performs poorly over a sustained period, will some or all of the JV’s exclusive access to certain markets be revoked? Or if the JV and parent are in an exclusive sales or supply arrangement, if one party to the agreement does not perform, does the arrangement become non-exclusive for the other party?

These six potential future events are all somewhat predictable, yet depending on the individual event, at least one-third of benchmarked JVs—and sometimes up to 80% of benchmarked JVs—have no language to address such situations (Exhibit 3).

More broadly, 73% of JVs in our data set failed to address more than three of these scenarios, and no JV included all six future-proofing provisions (though not all apply equally to every type of JV). While all the JVs we reviewed included at least one future-proofing provision, there is obvious evidence that JVs are failing to provide enough elasticity for a range of future contingencies.

Dealmakers can craft these future-proofing provisions to fit whatever their needs may be. For example, a multi-billion-dollar 50:50 aerospace and defense JV included a provision stating that a jointly-selected outside consultant would determine whether business opportunities were within or outside of the JV’s scope. This type of provision clearly defines the mechanism for pursuing business opportunities without leaving room for error.

Failing to plan for future contingencies can have serious consequences. For example, when Toys R Us and Amazon entered into an exclusive partnership in 2000 in which Amazon would exclusively sell Toys R Us toys, the parties did not build flexibility into the deal to contemplate Amazon’s fast-paced growth. At the outset, the partnership worked wonders for both parties—giving Toys R Us an online presence and Amazon a well-reputed product line. However, as Amazon’s success grew, it reportedly elected to violate the exclusive arrangement by expanding its toys department to include direct competitors of Toys R Us. Amazon argued, however, that it simply interpreted the exclusivity clause in a different way—claiming unsuccessfully that the company could allow third parties to offer toys for sale that Toys R Us elected not to sell on Amazon’s site. As a result of this act, Amazon was found in breach of contract and paid $51 million in settlement fees, while Toys R Us ultimately ended up being too far behind its competitors to have any hope at a strong online presence, contributing to its bankruptcy filing in 2018. The failure to plan for changes in partnership performance resulted in a significant cost for one partner, Amazon, and was strategically disastrous for the other, Toys R Us. Had the dealmakers for Toys R Us considered limiting exclusivity to a period of time, or pushed for a buy-out option, they might have had a better chance at catching up with and surviving the constantly evolving e-commerce world.

The Amazon and Toys R Us partnership is not the only example of exclusivity provisions that do not anticipate future change leading to the demise of partners’ relationships. Consider the case of joint venture formed between a technology leader and a traditional media firm, which committed to using the JV as its exclusive online channel in the nascent days of the internet. A decade later, it was clear to the traditional media firm that it needed a multi-pronged online strategy to be successful—necessitating a buyout of the technology partner in the hundreds of millions to sever the exclusivity clause. Had the traditional media considered provisions to address changes in technology and the market, like making exclusivity time-limited or including an option to buy-out the venture at a pre-agreed price if online news hit certain metrics, they might have been in a better position when the internet exploded in the 2000s.

However, if JV partners include thoughtful future-proofing features into JV agreements, they can build and manage long-term and successful JVs. For example, when BMW and Brilliance created BMW Brilliance, a joint venture to sell BMW cars in China, the parties clearly defined exclusivity and included several relevant future proofing provisions. The JV was limited to selling certain BMW models in China and was required to use BMW intellectual property and branding. Meanwhile, Brilliance could not manufacture or sell models in China that competed with the models the JV produced, and BMW could not compete with the JV in China. Despite these broad prohibitions, there were carve-outs to BMW’s obligations, allowing them to compete with the JV for sales in China up to 5% of JV volumes. On top of these arrangements, BMW-Brilliance included several future-proofing elements, including that BMW could meet market demand that the JV could not meet, and that neither parent could enter into any other partnership (JV or otherwise) that directly competed with the JV. These elements were highly successful, resulting in a JV that grew to 19,000 employees and €20B in revenue prior to BMW’s planned acquisition of a controlling stake for $4.2 billion after Chinese regulators loosened foreign ownership rules—the first global carmaker to do so.

Recommendations

Ultimately, developing non-competition and exclusivity terms requires JV parent companies to strike a delicate balance. On one hand, the parent companies will want to empower the JV company to be successful, which implies granting it some running room for growth, likely including a not overly-narrow authorized scope and some degree of exclusivity relative to the parents. Creating running room for growth will allow the JV to attract and motivate top talent, and avoid the need to constantly renegotiate the venture agreements.

On the other hand, individual parents will want to protect themselves against granting overly-broad and perpetual exclusivity to the venture, especially if the venture is in a highly-dynamic and fast-evolving industry, or has an uncertain performance prospects. For example, in a media industry joint venture we helped restructure in India, the international partner had agreed that the JV would be its exclusive vehicle to compete in India with a broad set of product segments. When the JV seriously underperformed over five years, the international partner was forced to negotiate an expensive exit in order to regain the rights to its brand in a critical growth market.

Individual parent companies may be able to protect themselves against such risks, of course. Well-structured exit and other legal provisions, including time-bound or conditional exclusivity, clear exit triggers, pre-agreed exit valuation methodologies, and the right to exit the venture through put or call rights, all provide potential escape hatches. For example, having a call right on the other partner’s shares, as well as the capital to exercise it, reduces the need to be anxious about exclusivity terms. Similarly, if a partner has decision rights over changes to scope, then concerns about the JV expanding to compete in the future are lessened.

Prior to drafting contractual terms, dealmakers should consider a number of strategic and practical facts and choices that may influence the choice of an exclusivity and non-competition regime. These include:

- Whether the parties are interested in creating a long-term sustainable business, versus a special purpose vehicle

- Whether either party has, or intends to have, a business adjacent to that of the JV

- Whether the JV is core to your company’s or partner’s strategy

- The pace of change and uncertainty within the JV’s product or geographic market, and underlying technology

- Whether the venture will enter into any purchase, sale, service, or licensing agreements with either parent company—and whether these agreements will have exclusivity provisions

- Whether your company is a natural buyer or natural seller of the JV in the future

The factors will each inform the breadth of exclusivity and non-compete provisions, and whether to include time-limitations or other carve-outs, and how to anticipate future events.

In particular, if there are asymmetries between the parties—such as one party having an adjacent business that it wishes to protect while the other desires for the JV to grow substantially—parties should be particularly attuned to exclusivity and non-competition provisions. In fact, dealmakers should anticipate where parties to a JV may be misaligned regarding exclusivity-related decisions and then structure solutions for how the parties will address such challenges if they arise down the road. [6]

***

Getting JV agreements right requires clearly defining non-competition and exclusivity limitations—potentially including carveouts—and anticipating future events. Doing so will make JVs more durable and elastic to future changes in a constantly evolving world, helping owner companies to profit from a JV like BMW Brilliance and avoid the costly consequences from a JV like Yamatake-Honeywell.

Endnotes

1See Case Study “Did Honeywell Create a Competitor?” in Benjamin Gomes-Casseres, The Alliance Revolution: The New Shape of Business Rivalry, Harvard University Press, 1998 (go back)

2As part of the buyout, the JV was renamed to Azbil. See Azbil Corporation Group History –https://www.azbil.com/corporate/company/history.html, accessed August 2020(go back)

3For additional discussion of joint venture non-competes, see Eduardo Gallardo, “Defining a Joint Venture’s Scope of Business: Key Issues,” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, accessed August 2020 https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2012/09/24/defining-a-joint-ventures-scope-of-business-key-issues/(go back)

4While exclusivity and non-competition arrangements are generally memorialized in the main joint venture legal agreement (e.g., the Shareholders Agreement, Members Agreement, LLC Agreement, Joint Venture Agreement), these provisions may also be included in ancillary agreements, including licenses, services, or supply agreements—which was beyond the scope of this analysis.(go back)

5Partners may impose limitations on each other or on the JV regarding non-solicitation of employees. This analysis does not address non-competition arrangements with respect to individual employees and instead focuses on restrictions on the JV’s or parents’ businesses more generally.(go back)

6See Bamford, James, “How to Make a Joint Venture Succeed: Conducting a Pre-Mortem.” Water Street Insights (Feb. 29, 2016).(go back)

Print

Print