Eli Kasargod-Staub is co-founder and executive director and Jessie Giles is research director at Majority Action. This post is based on their Majority Action report. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: The Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee by Max M. Schanzenbach and Robert H. Sitkoff (discussed on the Forum here); and Companies Should Maximize Shareholder Welfare Not Market Value by Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales (discussed on the Forum here).

In the face of a global pandemic, climate-driven hurricanes, wildfires, and other extreme weather events, and the subsequent economic crisis destroying lives, livelihoods, and property, it is clear that systemic risks are the greatest threat to global economic and financial stability. To investors’ portfolios, the systemic risk of climate change is large, material, and undiversifiable–as well as undeniable. Investors and companies have been on notice since 2018 that the global economy must nearly halve carbon emissions in the next decade and reach net-zero emissions by 2050 to have just a 50% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C and avoiding the worst effects of a climate catastrophe.

In order to manage these systemic portfolio risks, investors must move beyond disclosure and company-specific climate risk management frameworks, and focus on holding accountable the relatively small number of large companies whose actions are a significant driver of climate change. Unfortunately, despite some recent progress, the largest systemically important carbon emitters and enablers in the U.S.–the energy, utility, automotive, and financial services sectors–remain far behind in the urgent business transformation needed to achieve a net-zero carbon future.

To change company behavior to have a chance to avoid further climate catastrophe, shareholders who own these companies have the power and duty to hold their boards of directors accountable for the failure to align their strategies with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Given both the urgency of the transformation required and the influence provided by their holdings in these companies, leading investors worldwide are mobilizing to hold the largest emitters accountable to implement concrete and immediate decarbonization plans. Despite this, BlackRock and Vanguard, the world’s largest asset managers and largest shareholders of the vast majority of S&P 500 companies, continue to undermine global investor efforts to promote responsible climate action at these critical companies–even as they publicly tout their commitment to addressing the climate crisis.

This post reviews the contributions, or lack thereof, of the world’s 12 largest asset managers to hold large U.S. energy, utility, financial services and automotive manufacturing companies accountable to combat climate change and the risks it poses to long-term shareholders and other stakeholders. Collectively they have $27.65 trillion in assets under management. As managers of investments and retirement savings for millions of people in the U.S. and abroad, they are responsible for serving as stewards for the interests of long-term investors of all sizes. This post measures how these asset managers voted on director elections and advisory votes on top executive compensation (also known

as “say-on-pay” votes) at large-capitalization U.S. companies in these critical industries, as well as their performance on critical climate-related shareholder proposals at these and other S&P 500 companies.

The key findings of this review include:

- BlackRock and Vanguard voted for 99% of U.S. company-proposed directors across the energy, utility, banking and automotive sectors reviewed in this post. BlackRock voted for 100% of company-proposed directors at the banking and auto companies included in this analysis, 99.7% at utilities, and 98% at oil & gas companies. Vanguard voted for 100% of company-proposed directors across the oil and gas, banking, and automotive companies, and in favor of 99% at utilities. BlackRock’s 2020 votes come just months after CEO Larry

Fink declared that BlackRock would put climate change at the center of its investment strategy. - BlackRock and Vanguard not only voted with management more often than most of their asset manager peers; they were just as likely to support management at utilities that had made a net-zero commitment prior to their annual meeting as at those that had not made such a commitment.

- BlackRock and Vanguard voted overwhelmingly against the climate-critical resolutions reviewed in this report, with BlackRock supporting just 3 of the 36, and Vanguard only 4. At least 15 of these critical climate votes would have received majority support of voting shareholders if these two largest asset managers had voted in favor of them. These included proposals that would have held JPMorgan Chase’s board accountable for its role as the world’s largest fossil fuel financier, and as was also the case in 2019, a proposal to bring much-needed transparency to the lobbying efforts of Duke Energy, one of the largest and highest-emitting electric utilities in the U.S.

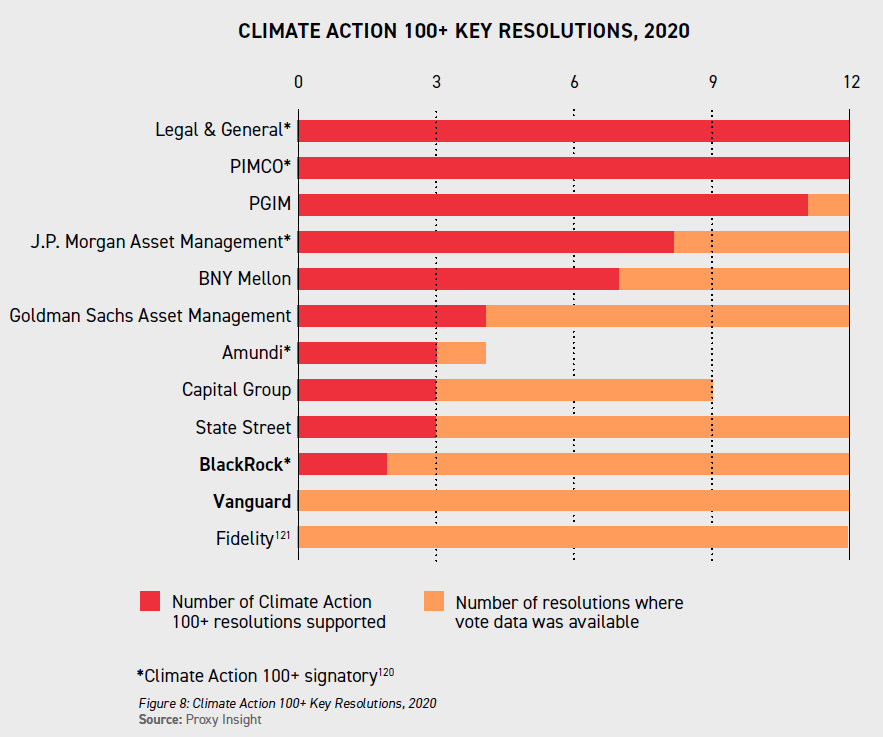

- BlackRock voted against 10 of the 12 of the shareholder proposals flagged by the $47 trillion Climate Action 100+ investor coalition, despite joining that coalition earlier in 2020, undermining the largest global investor efforts for accountability and transparency in the energy, utility, industrial and automotive sectors.

- In contrast, other large asset managers are choosing to set and enforce policies to hold corporate boards accountable if climate-related concerns are not adequately addressed. Legal & General Investment Management and PIMCO had the highest rate of voting against management-proposed director candidates in the energy, utility, banking and automotive sectors. Legal & General and PIMCO also supported all of the shareholder proposals analyzed in this study, voting in favor of improved emissions disclosures and reduction plans, transparency regarding corporate political influence activity, and governance reforms to improve accountability to long-term shareholders.

In response to growing criticism of their voting behavior, BlackRock and Vanguard have begun to make limited disclosures of their voting decisions on climate issues, and BlackRock has said it will consider voting against directors of companies that fail to adequately manage climate risk. But aside from a small number of votes, market leaders BlackRock and Vanguard overall chose to continue to shield management across these climate-critical sectors in the U.S. from accountability, serving as a roadblock for global investor action on climate.

This post recommends that asset owners review their voting policies to enable them to vote against directors of companies with systemic importance to the climate if those companies are failing to make the necessary transition to a net-zero future. Given the urgency of the need to set companies on the path to net-zero, it calls on asset owners to vote against chairs and lead independent directors at systemically important carbon emitters that have failed to set targets of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the latest in the 2021 shareholder season. Finally, this post recommends that asset owners closely examine the proxy voting activities of the asset managers they engage, demand greater transparency on those managers’ voting decisions, call the asset managers to account for inadequate voting policies and practices, and consider those activities when evaluating and selecting asset managers.

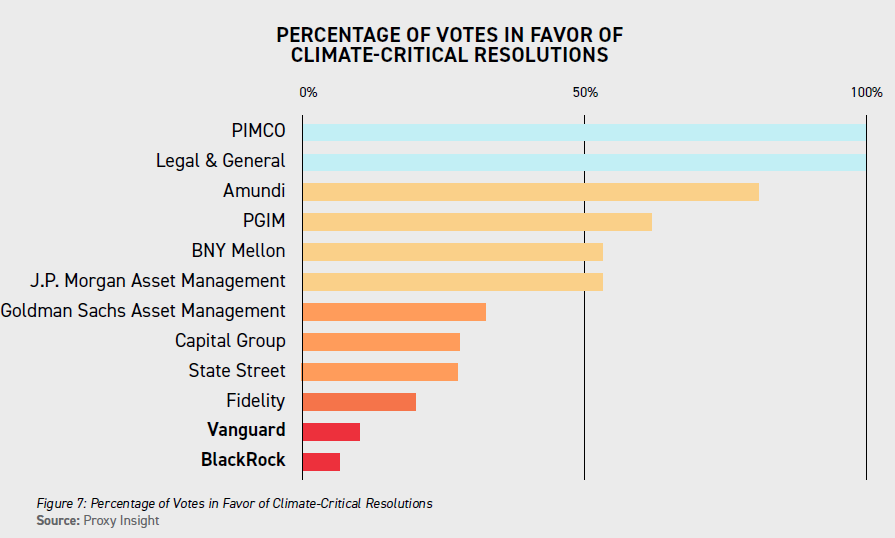

Performance of Asset Managers on Key Climate Shareholder Resolutions in 2020

In 2020, Majority Action reviewed 36 climate critical shareholder resolutions. Of these, nine were directly related to the business and physical risks of climate change; nine proposed independent chairs at fossil fuel intensive and climate critical companies; and 18 were related to the political and lobbying activities of key companies. Across all 36 resolutions, Legal & General and PIMCO voted most consistently in favor. By contrast, BlackRock, Vanguard, and Fidelity demonstrated the lowest level of support for these resolutions, voting for them less than 20% of the time.

Climate Action 100+

In 2020, Climate Action 100+, the largest global investor coalition on climate change representing $47 trillion in assets under management, highlighted 12 key resolutions at its focus companies. These included resolutions supporting independent chairs at Dominion Energy, Duke Energy, ExxonMobil and Southern Company, as well as lobbying disclosure resolutions at Caterpillar, Duke Energy, ExxonMobil, Ford Motor Company, General Motors, Chevron, Delta Air Lines, and United Airlines. Despite joining the Climate Action 100+ network in early 2020, BlackRock supported only two of the 12 resolutions. In contrast, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, which also joined Climate Action 100+ in 2020, supported eight of the 12 resolutions.

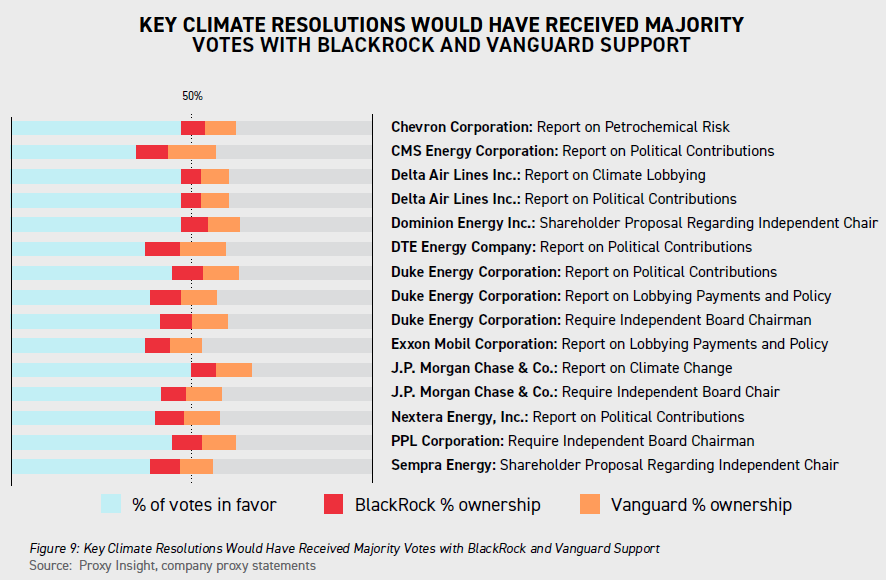

Key climate resolutions would have received majority votes with BlackRock and Vanguard support

As in prior years, a number of these key resolutions would likely have received majority support had BlackRock and Vanguard supported them.122 These two asset managers held more than 5% of common stock outstanding in each of the 23 companies with critical climate resolutions. BlackRock and Vanguard were among the least likely to support the shareholder resolutions identified in this post. BlackRock and Vanguard’s holdings are so significant that at least 15 of these resolutions would have received majority support if both of these asset managers had voted in favor of them.

For the second year in a row, a proposal at Dominion Energy asking for an independent chair of the board received wide shareholder support just shy of the majority threshold, at 46.6%. The resolution was supported by the proxy advisor ISS. Shareholder support for an independent chair increased from 39.7% in 2019. Vanguard (8.2%) and BlackRock (7.0%) together held more than 15% of Dominion shares, but neither voted for the resolution. Support from either would have not only allowed the resolution to pass, but also sent an unmistakable message to management about the need for change. Supporters of this resolution pointed to Dominion’s investments in the controversial Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP), an $8 billion project that was “notable for delays, cost overruns, and environmental and social risks.” They also criticized Dominion’s current lead independent director for his excessive tenure as well as lack of experience outside the fossil fuel industry, adding that the board structure was not well-suited for independent leadership of the company.

Dominion announced shortly after the annual general meeting that it would cancel the ACP project, saying that additional delays and litigation costs made the project “too uncertain to justify investing more shareholder capital.” The company said that it would take a $2.8 billion charge in the second quarter of 2020 related to the ACP, explaining that prolonged delays due to activist opposition, permit problems, a short-term hit on gas demand from the global pandemic as well as longer-term changes due to growing consumer interest in clean energy contributed to the demise of the controversial project.

While Dominion Chair and CEO Tom Farrell relinquished his role as CEO effective October 1, 2020, in the wake of this expression of shareholder concern, the board is still not chaired by an independent director, and the company promoted the executive who led the ill-fated ACP project, Diane Leopold, to be sole Chief Operating Officer responsible for all operating segments.

At J.P. Morgan Chase, two resolutions would have received majority support this year if Vanguard or BlackRock—which held 7.9% and 6.7% of JPMorgan Chase shares, respectively—had supported them. One resolution asked JPMorgan Chase to issue a report explaining if and how it intends to align its lending practices to goals of the Paris Climate Accord, citing concerns about the company’s record of financing fossil fuel companies and the lack of targets to reduce its lending-related GHG emissions. Climate activists have called JPMorgan Chase, which provided almost $269 billion in lending and underwriting support to the industry between 2016 and 2019, the “#1 banker of fossil fuels.” The resolution received the support of ISS as well as substantial shareholder support, with 49.6% of votes cast in favor.

Neither Vanguard nor BlackRock supported this widely-backed measure. Vanguard, in a rare explanation of its vote on a climate-critical resolution, said that while “financial services firms should not delay their climate reporting,” it found JPMorgan’s practices in line with those of its peers and did not support the resolution. BlackRock sided with management, asserting, “Company already has policies in place to address these issues.”

Shareholders also asked JPMorgan to adopt an independent board chair for the eighth time since 2010. The resolution received 41.9% shareholder support, the highest in the past decade. The proposal’s supporting statement raised concerns regarding the independence of JPMorgan Chase’s current lead independent director Lee Raymond, the former ExxonMobil CEO, who has been on the board for 33 years and in key leadership roles for almost two decades, adding that “long tenure … is the opposite of independence.” Once again, neither Vanguard nor BlackRock supported this critical resolution. Their combined votes, amounting to almost 15%, would have more than ensured majority support. While Vanguard has not provided any explanation for its vote, BlackRock has said, “Company has a designated lead director who fulfils the requirements appropriate to such role.”

At Duke Energy, shareholders have voted on a resolution asking the company to fully disclose its lobbying activities and expenditures every year since 2016, except for 2018, when it was withdrawn. The resolution highlighted Duke’s lobbying at the state level and through third-party groups, including trade associations and tax-exempt organizations that write model legislations. It cited reputational risks associated with lobbying that “contradicts company public positions.” Of particular concern to shareholder proponents were Duke’s payments to groups, including the Business Roundtable, Edison Electric Institute, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and American Legislative Exchange Council, whose positions “do not align with its stated commitment to a low carbon future.” Shareholder support for this resolution ranged in the low- to mid-30% range between 2016 and 2019 but increased to its highest this year at 42.4% after proxy advisor ISS recommended a vote in favor. Vanguard, the holder of 8.5% of Duke’s shares, did not support this resolution. If Vanguard had voted in favor, the resolution would have passed the majority threshold after many years of consistent shareholder support. BlackRock also voted against this resolution, although it would not have been able to swing

the result on its own.

Also voted on at Duke Energy was a shareholder resolution asking for an independent chair of the board. It noted that the Duke CEO has served as the chair of the board since 1999 except for two transition periods, and that the current independent lead director has served since 1990, compromising his independence. It also made the case that independent board leadership would be “particularly useful to oversee the strategic transformation necessary for Duke to capitalize on the opportunities available in the transition to a low carbon economy.” This resolution received 40.1% shareholder support and the support of ISS. Neither Vanguard (8.5% ownership) nor BlackRock (7.0%) voted for it; their combined support would have led to majority support for the resolution. While Vanguard did not provide a reason for this vote, BlackRock cited the existing role of lead independent director as its reason for opposition.

Shareholders at Delta Air Lines asked the company this year to align its lobbying activities to the goals of the Paris Agreement, or “limiting average global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius.” This first-year resolution received strong shareholder support of 45.9%, missing the threshold for majority by less than five percent. The proposal cited concerns about systemic risks that climate

change pose to economies and investment portfolios, as well as the role of trade associations and other political organizations that “present forceful obstacles to progress in addressing the climate crisis.” Vanguard held 6.9% of the company’s shares and BlackRock held 5.4%. Both opposed this resolution; support from either one would have pushed it past the majority threshold. BlackRock explained its decision stating that Delta was working on increasing its disclosures on political contributions and lobbying, and thus, “support for the shareholder proposal is not warranted at this time.” This contrasts with BlackRock’s support of a similar resolution at Chevron, which it said was “in the best interests of shareholders to have access to greater disclosure on the issue.”

A first-year resolution asked Chevron to report on the “public health risks of expanding petrochemical operations and investments” in areas increasingly affected by climate change. The resolution focused on the Chevron Phillips Chemical Company, a subsidiary, and the “financial, health, environmental, and reputational risks” of maintaining and building chemical facilities along the Gulf Coast of the United States, an area prone to hurricanes. Shareholder proponents challenged an “evasion of responsibility regarding the increasingly important topic of climate risk” and said that Chevron did not provide shareholders with “sufficient analysis and disclosure on managing growing risks to its petrochemical operations.” About 46% shareholders supported the measure; had either Vanguard or BlackRock, which held 8.4% and 6.7% of Chevron shares, respectively, supported it, it would have passed the majority threshold. BlackRock asserted that Chevron has “robust board oversight and operational systems” and “demonstrates adequate management of the physical risks associated with climate change.”

BlackRock’s vote on this proposal diverged from its vote on another resolution at Chevron, asking the company to report on how its lobbying activities aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement and how it planned to mitigate the risks of misalignment. “Corporate lobbying activities that are inconsistent with meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement present regulatory, reputational and legal risks to investors,” the resolution urged, stressing concerns about trade associations and other political organizations that “too often present forceful obstacles to progress in addressing the climate crisis.” BlackRock voted in favor of the resolution because “[w]e believe it is in the best interests of shareholders to have access to greater disclosure on this issue.” Without BlackRock’s support, the resolution would not have reached majority support. Vanguard voted against the resolution.

Despite Chevron’s failure to alter its capital expenditures to align its oil and gas production to a carbon budget consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement and its documented history of using its influence to undermine climate mitigation policies, BlackRock stated that it “recognize[s] and applaud[s]” Chevron’s current reporting and “considers Chevron a leader among US peers with regard to board oversight of climate risk, strong corporate governance practices, and reporting in line with SASB and the TCFD.”

Recommendations

Asset owners can do more to hold asset managers accountable for managing their proxy voting strategies to ensure companies are adequately prepared to face the unprecedented risks posed by climate change. Asset owners have an obligation to their beneficiaries to carry out oversight of corporate boards through monitoring, engagement, and proxy voting. Asset owners therefore should urge their asset managers to wield their power and influence to press companies to plan adequately for a net-zero carbon future and mitigate the risks of catastrophic climate change to investors.

Specifically, asset owners should:

- Review and update voting policies: Asset owners should review and update their own proxy voting guidelines to allow them to hold boards accountable through votes on director elections for the climate performance of systemically important carbon emitting companies. These policies should enable asset owners to vote against board chairs, lead independent directors, committee chairs, and, if necessary, entire boards at companies that fail to set net-zero targets and put in place the necessary plans to meet those targets.

- Hold boards accountable for climate performance: Starting in 2021, asset owners should vote against or withhold support from the board chair and lead independent director (where the position exists) at companies that are systemically important carbon emitters and have failed to commit to net-zero emissions by 2050. Fossil-fuel intensive companies and those in sectors with systemic importance to the climate have been on notice for many years that they must transition their operations and products to achieve net-zero emissions by no later than 2050 if the world is to avoid the worst effects of catastrophic climate change. Investors should immediately begin to hold directors accountable for failing to recognize this reality.

- Review relationships with existing asset managers in light of proxy voting performance, and seek alternative asset managers if necessary: As major clients of asset managers, asset owners should engage with their current asset managers over their voting record and plans for holding boards accountable for systemic climate risk. They should expect full transparency and sufficient contemporaneous explanation regarding the reasoning and justification for votes cast by the asset manager. Asset owners should also consider incorporating criteria regarding proxy voting on systemic climate risk and at climate-critical companies into their asset manager search criteria, requests for proposals, and assessments.

The complete publication, including footnotes and appendix, is available here.

Print

Print