Keith E. Gottfried is partner at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP. This post is based on his Morgan Lewis memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here); Dancing with Activists by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, and Thomas Keusch (discussed on the Forum here); and Who Bleeds When the Wolves Bite? A Flesh-and-Blood Perspective on Hedge Fund Activism and Our Strange Corporate Governance System by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Shareholder activism in the United States and worldwide was noticeably down in 2020 when compared to 2019, and that decline was largely due to the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. However, for US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registered closed-end investment funds, COVID-19 had the opposite effect. In the wake of the market dislocations that were driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, shareholder activism at closed-end funds was up noticeably in 2020, with closed-end funds experiencing more activist campaigns and proxy contests than in any other year between 2008 and 2020.

While shareholder activism at closed-end investment funds is not a new development and can be traced back to at least the early 1990s, it has historically been a niche area of shareholder activism dominated by a very small group of activist investors that target closed-end funds for the primary purpose of unlocking the discount between a fund’s share trading price and its per-share net asset value (NAV).

The COVID-19-driven market dislocations that occurred in March 2020 resulted in a significant, though relatively short-lived, widening of the discounts between a closed-end fund’s share trading price and its per-share NAV. This widening of the average NAV discount for US closed-end funds, which came close to the previous all-time record high set in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, created an attractive opportunity for activist investors to accumulate large positions in the closed-end funds most impacted by the market dislocations and, thereby, lay the groundwork for activism campaigns to pressure closed-end funds to pursue liquidity events like self-tender offers that would allow activist investors to monetize such NAV discounts.

It is possible that the success that activist investors had during 2020, in the wake of the COVID-19 market dislocations, in pursuing proxy contests and other activism campaigns at closed-end funds and in driving the monetization of the funds’ NAV discounts may encourage more activism campaigns against closed-end funds, including by activist investors that heretofore have not targeted closed-end funds. It is also possible that the experiences of the numerous closed-end funds that had to respond to campaigns waged by activist investors in 2020, and the concessions that some of those funds agreed to make to avoid costly and distracting activism campaigns—including agreeing to a liquidity event to facilitate the monetization of the NAV discount sought by the activist investor—may be a “wakeup call” that closed-end funds need to more actively and regularly prepare for shareholder activism in a manner more akin to the approach that, in recent years, has been followed by larger, publicly traded operating companies.

How COVID-19 Impacted Shareholder Activism at Closed-End Funds During the 2020 Proxy Season

As concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic began to take hold in March 2020, closed-end funds experienced significant market volatility and dislocations driven by the pandemic. Closed-end funds are more vulnerable to the impacts of a market dislocation because they often use leverage and are less liquid than other exchange-traded securities. Accordingly, as the markets began to falter toward the middle of March 2020, numerous closed-end funds experienced a significant widening of the discounts between the fund’s share price and its per-share NAV. The average NAV discount for the United States’ 498 closed-end funds hit 21.6% on March 18, 2020, the second largest NAV discount ever experienced, with the largest being 27.4% in October 2008 in the wake of the financial crisis.

While the COVID-19-driven widening of NAV discounts at closed-end funds was relatively short-lived and the average NAV discount settled back down to 8.6% by late April 2020, the significant widening of the NAV discounts that had occurred at many closed-end funds a month earlier created a very attractive opportunity for activist investors to accumulate large positions in these funds, and set the stage for a future activism campaign focused on monetizing the discount between a fund’s share trading price and its per-share NAV. It was no surprise then that, as shareholder activism and proxy contests at other sectors slowed down considerably during 2020, there were more activism campaigns and proxy contests at closed-end funds than during any other year between 2008 and 2020.

Trends In Shareholder Activism at Closed-End Funds

Below are some statistics on shareholder activism at closed-end funds in 2020, as compared to past years:

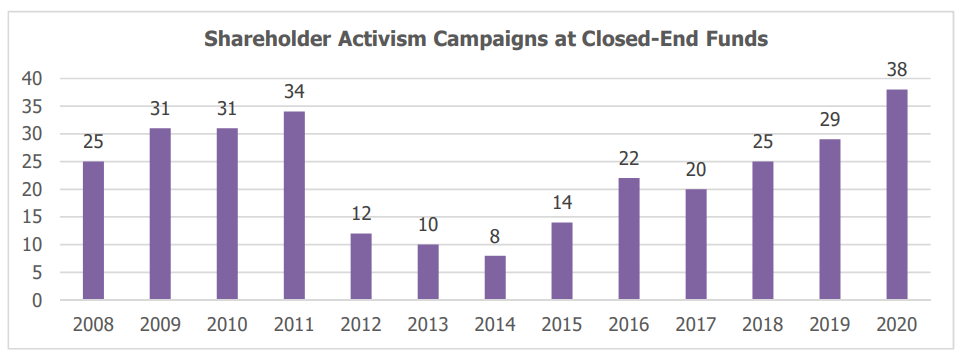

- 38 activism campaigns were waged at closed-end funds in 2020, compared with 29 in 2019, the most in any year between 2008 and 2020.7Between 2008 and 2020, the year with the second highest number of activism campaign at closed-end funds was 2011 when there were 34.

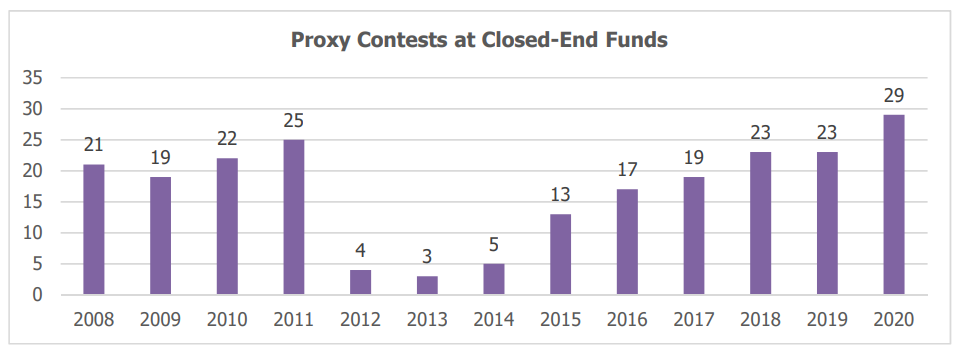

- 29 proxy contestswere waged at closed-end funds in 2020, compared with 23 in 2019, the most in any year between 2008 and 2020. Between 2008 and 2020, the year with the second highest number of proxy contests at closed-end funds was 2011 when there were 25.

The chart below depicts the number of shareholder activism campaigns at closed-end funds from 2008 to 2020:

The chart below depicts the number of proxy contests at closed-end funds from 2008 to 2020:

How Shareholder Activism at Closed-End Funds Differs From Shareholder Activism at Operating Companies

While the process of waging an activism campaign at a closed-end fund is very similar to the process followed for an operating company, there are numerous ways that shareholder activism at closed-end funds is noticeably different, including the following.

Shareholder Activism at Closed-End Funds Tends to Be a Very Specialized Niche Area of Shareholder Activism Dominated by a Very Small Group of Activist Investors

Most activist investors are industry agnostic and will target companies in almost any industry where they see an attractive opportunity. While some activist investors have developed substantial expertise in a selected number of industries, there are very few industry sectors that have activist investors exclusively focused on that industry. Among the industry sectors with activist investors that focus their activism activity almost exclusively, if not exclusively, on one sector is closed-end funds.

In addition, the closed-end fund sector is one of the few industry sectors that is targeted by a relatively small group of activist investors and most of the campaigns are waged by an even smaller subset of that group. While there are dozens of activist funds that focus on operating companies, very few of those activist investors target closed-end funds. Two activist investors accounted for all 29 of the proxy contests that were waged against closed-end funds in 2020. While there were 8 activist investors that participated in activism campaigns against closed-end funds in 2020, 30 of the 38 activism campaigns that were waged against closed-end funds in 2020 involved only two activist investors.

Closed-End Funds Tend to Be Less Prepared for an Activist Investor Than an Operating Company

While many publicly traded operating companies regularly review their structural vulnerabilities and defenses to a hostile takeover and/or an activist investor; periodically update their advance notice, special meeting, and other provisions in their bylaws and other governing documents that would be relevant were an activism campaign to be threatened against the company; and have developed detailed “break-glass” plans for responding to activist investors, these practices do not appear to have yet taken hold among many closed-end funds to the same degree that they have at operating companies.

Until Recently, Closed-End Funds Were Not Able to Avail Themselves of the Protections of a Control Share Acquisition Statute

Until recently, guidance from the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management discouraged closed-end funds from opting into the control share acquisition statute of their state of organization. Control share acquisition statutes are state takeover defense laws that generally deter or prevent a person from acquiring control of an entity by altering or removing the voting rights that a person would have if a person acquired, directly or indirectly, the ownership of, or the power to direct the vote of, control shares as defined in the specific state control share acquisition statute.

In a letter issued in 2010 that came to be known as the Boulder Letter, the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management, addressing the interplay of Section 18(i) of the Investment Company Act of 1940, as amended (the 1940 Act), and the Maryland Control Share Acquisition Act (MCSAA), took the position that opting into the MCSAA would be “inconsistent with the fundamental requirements of Section 18(i) of the Investment Company Act of 1940 that every share of stock issued by [an investment company] be voting stock and have equal voting rights with every other outstanding voting stock.” While the Boulder Letter only addressed the interplay of Section 18(i) of the 1940 Act and the MCSAA, the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management noted that its analysis may be applicable to other state control share acquisition statutes. On May 27, 2020, the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management issued a Staff Statement withdrawing the Boulder Letter, and indicated therein that “[t]he staff would not recommend enforcement action to the Commission against a closed-end fund under section 18(i) of the Act for opting in to and triggering a control share acquisition statute if the decision to do so by the board of the fund was taken with reasonable care on a basis consistent with other applicable duties and laws and the duty to the fund and its shareholders generally.” It is important to note that, while the Staff Statement withdrawing the Boulder Letter removes a significant impediment to a closed-end fund opting into a control share acquisition statute, it represents only the view of the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management; is not a rule, regulation, or statement of the SEC; and has no legal force or effect.

While the withdrawal of the Boulder Letter may eventually lead to more closed-end funds opting into control share acquisition statutes, in the near term, there are two obvious impediments to a fund doing so. One is that not every state has a control share acquisition statute. Most closed-end funds are domiciled in Delaware, Maryland, or Massachusetts. While each of Maryland2 and Massachusetts has a control share acquisition statute, Delaware does not. So a fund organized in Delaware could not avail itself of the protection of a control share acquisition statute unless it first re-domiciled to a state with such a statute, which is a time-consuming and logistically challenging process. The other impediment is that Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. (ISS), a leading proxy advisory firm, has recently adopted a policy applicable to closed-end funds, effective for meetings that occur on or after February 1, 2021, that provides that ISS will recommend a vote against or withhold from the fund’s nominating/governance committee members (or other directors on a case-by-case basis) at closed-end funds that have not provided a compelling rationale for opting into a control share acquisition statute. Further, to date, ISS has not publicly disclosed what it would regard as a “compelling rationale” such that a fund would be able to avoid ISS issuing a negative vote recommendation. ISS has specifically disclosed that the change in its voting policy is in response to the decision of the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management to withdraw the Boulder Letter and no longer recommend enforcement action to the SEC against a closed-end fund under Section 18(i) of the 1940 Act for opting into a control share acquisition statute.

Not Likely for a Closed-End Fund to Adopt a Shareholder Rights Plan/Poison Pill to Deter or Fend Off an Activist Investor

To date, it has been relatively rare, though not unprecedented, for a closed-end fund to adopt a shareholder rights plan, more commonly known as a poison pill. While, as of December 4, 2020, there are 210 poison pills in force at US-incorporated companies, none of those poison pills were adopted by closed-end investment funds. Close to two dozen poison pills were adopted by publicly traded entities during March 2020 in the immediate wake of the market dislocations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, notwithstanding that these market dislocations widened NAV discounts for many closed-end funds and made them more vulnerable to activist investors, no closed-end fund adopted a poison pill in the wake of these market dislocations. While a poison pill does not prevent an activism campaign, were one adopted by a closed-end fund, it could have the effect of deterring an activist investor or a group that includes the activist investor from accumulating an amount of the closed-end fund’s securities that equals or exceeds the poison pill’s triggering ownership threshold and, thereby, may cause the closed-end fund to be a less attractive target for an activist investor.

One of the reasons that may account for the rarity of poison pills adopted by closed-end funds is that, historically, there has been some uncertainty as to whether a poison pill, as typically structured, complies with various provisions of the 1940 Act. The concerns with whether a poison pill complies with the 1940 Act have been focused on the provisions thereof that (1) require that the share purchase rights that would be issued pursuant to the poison pill be issued proportionately to a class or classes of shareholders, (2) require that each share of a closed-end fund have equal voting rights, and (3) require that closed-end fund shares not be sold at less than NAV. However, when a poison pill adopted by a closed-end fund was challenged in federal court in 2004 on the basis that it did not comply with the foregoing requirements of the 1940 Act, the US District Court for the District Court of Maryland ruled that the adopted poison pill did not violate any of those requirements of the 1940 Act.

Most poison pills recently adopted by operating companies have a term of approximately one year, which is significantly shorter than the 10-year term that used to be common and quite standard in practice before governance standards evolved to the point where lengthy prophylactic poison pills become disfavored. In contrast, a poison pill adopted by a closed-end fund with a one-year term would run afoul of Section 18(d) of the 1940 Act, which provides that a closed-end fund cannot issue any rights to purchase a security except where the rights expire not later than 120 days after their issuance.

Accordingly, a poison pill adopted by a closed-end fund cannot have a term of more than 120 days. However, it does appear that a closed-end fund can adopt successive poison pills each with a term of no more than 120 days. In a 2007 federal court ruling involving the same poison pill discussed above that was challenged in 2004, the US District Court for the District Court of Maryland ruled that serial poison pills, each with a term of not more than 120 days, do not violate the 1940 Act.

Activist Investors at Closed-End Funds Tend to Acquire a Much Higher Percentage of Their Targets Than Activist Investors at Operating Companies

In 10 of the 38 activism campaigns, and seven of the 29 proxy contests, that were brought at closed-end funds in 2020, the activist investor beneficially owned more than 20% of the fund’s shares. That is noticeably higher than what we typically see in connection with activism campaigns at publicly traded operating companies. In situations where the activist investor acquires beneficial ownership of 20% or more of the fund’s shares and assuming all of those shares were acquired in advance of the annual meeting’s record date, the activist investor has a significant voting advantage in a proxy contest against the fund.

It is also worth noting that where the activist investor acquires beneficial ownership of more than 10% of the fund’s shares, the activist investor becomes subject to Section 16(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the Exchange Act), also known as the “short-swing profit rule.” Pursuant to the “short-swing” rules adopted under Section 16(b) of the Exchange Act, where the activist investor beneficially owns more than 10% of the fund’s shares, to the extent that it purchases and sells any securities of the fund within a period of less than six months, the activist investor would be required to disgorge to the fund any “short-swing” profits as such profits are determined pursuant to the SEC’s “short-swing” rules.

The increased propensity of an activist investor to acquire a relatively large stake in a closed-end fund illustrates why the ability of a closed-end fund to opt into a control share acquisition statute is increasingly relevant, particularly in light of the recent withdrawal by the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management of its previous position that threatened enforcement actions against closed-end funds that opted into control share acquisition statutes. It also illustrates why a poison pill prepared in compliance with the 1940 Act could be useful to a closed-end fund trying to deter an activist investor from acquiring such a large stake in the fund.

Closed-End Funds Are Often Organized as Trusts Rather Than Corporations So They Are Subject to Different Statutory Requirements Than Operating Companies Organized as Corporations

Most publicly traded operating companies are organized as corporations subject to the corporations statute of their state of incorporation. In contrast, SEC registered closed-end funds are often organized as trusts under the laws of Delaware, Maryland, or Massachusetts. Instead of articles of incorporation, such closed-end funds have as their governing charter document a declaration of trust and, instead of directors, they have trustees. For example, some closed-end funds are organized as Delaware statutory trusts and those funds are governed by the Delaware Statutory Trust Act, as amended (DSTA), rather than the Delaware General Corporation Law, as amended (DGCL). In many cases, the DSTA provides a closed-end fund with significantly more flexibility on how to structure its governance and its relationship with its shareholders than would be permitted for a corporation subject to the DGCL.

The Disclosure and Securities Law Aspects of an Activism Campaign at a Closed-End Fund Are Overseen by a Different SEC Division and Office Than Is the Case for an Operating Company

When an activist investor wages an activism campaign against a publicly traded operating company, the disclosure and securities law issues related thereto are overseen by the SEC Division of Corporation Finance—Office of Mergers and Acquisitions and that office is responsible for reviewing the filings made by the activist investor and the closed-end fund. However, when the activism campaign takes place at an SEC registered closed-end fund, the SEC Division of Investment Management—Disclosure Review and Accounting Office reviews the filings made by the activist investor and the closed-end fund. While the proxy rules applicable to an activism campaign at an SEC registered closed-end fund are generally the same as those applicable to an activism campaign at a publicly traded operating company, how those rules are interpreted and enforced by the respective staffs of the SEC Division of Investment Management—Disclosure Review and Accounting Office and the SEC Division of Corporation Finance—Office of Mergers and Acquisitions may not always be the same.

The Closed-End Fund’s Charter May Narrowly Limit the Matters That Shareholders May Vote On

In the context of closed-end funds, the fund’s declaration of trust or other charter document may provide that shareholders are only permitted to vote on certain enumerated matters, such as the following: (1) the election of trustees, (2) the removal of trustees, (3) any investment advisory or management contract to the extent required by the 1940 Act, (4) the amendment of the declaration of trust to the extent provided for in the declaration of trust, (5) the termination of the fund, (6) the conversion of the fund to an open-end investment company, (7) the reorganization of the fund, (8) such additional matters relating to the fund as may be required or authorized by the 1940 Act, other applicable law, the declaration of trust, or the fund’s bylaws, or any registration of the fund with the SEC or any state, and (9) such matters as the trustees may consider desirable. With such a restrictive list, an activist investor seeking to submit an advance notice of business it intends to propose at a meeting of the fund’s shareholders is significantly limited in the types of matters that it can propose.

One of the other consequences of the closed-end fund’s declaration of trust or other charter document narrowly limiting the types of matters that shareholders may vote on is that an activist investor will find that it is very difficult to avoid having the closed-end fund exclude a shareholder proposal submitted pursuant to Rule 14a-8 of the Exchange Act. The SEC staff has consistently taken the position that an SEC registrant can exclude a Rule 14a-8 shareholder proposal pursuant to Rule 14a-8(b) in circumstances where the shareholder proponent is not permitted to vote on the subject of the proposal, such as when the declaration of trust or other charter document limits the types of matters that shareholder can vote on.

In addition, where an activist investor is limited in the types of proposals it can make, it may end up including proposals in its advance notice to the fund that it may not necessarily be all that interested in seeing implemented, but which it views as helpful to further its efforts to apply pressure on the fund. For instance, an activist investor may propose terminating the fund’s investment adviser, not because it has any strong-held belief that the adviser should be terminated, but because, pursuant to Section 15(a) of the 1940 Act, the fund cannot prevent shareholders from voting on such a proposal.4 Arguably, if activist investors had wider latitude to make shareholder proposals at closed-end funds, we would see more variety in the types of proposals made and, perhaps, more proposals that have a more direct nexus to the activist investor’s primary objective—causing the fund to pursue a liquidity event that unlocks the discount between the fund’s share trading price and its NAV.

Activist Investors at Closed-End Funds Are Generally Focused on One Path to Unlock Shareholder Value: Monetizing the Discount Between the Fund’s Trading Price and Its NAV

When an activist investor targets an operating company, it typically has an investment thesis that if the company pursues one or more of the activist investor’s demands, shareholder value will be unlocked and the activist investor will, thereby, be able to benefit along with other shareholders. That thesis may take any number of forms and an activist investor’s demands may include any or a combination of the following: (1) sale of the company, (2) divestiture of noncore businesses, (3) adoption of asset-light strategies, (4) changes in the company’s management and/or board of directors, (5) changes in how the company allocates capital, (6) optimization of the company’s capital structure, (7) return of cash to shareholders through stock repurchases or dividends, (8) shift in the company’s strategy, and (9) reduction of the company’s expenses or other actions to expand margins. This is, of course, not an exhaustive list and activist investors continue to become more sophisticated and nuanced in the demands they make to further their investment theses.

It is also the case that the types of demands an activist investor may make will depend greatly on the company’s industry and the opportunities to unlock value that may be very specific to that company and/or industry and/or the overall macroeconomic environment. Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic has created value enhancement opportunities for activist investors to pursue that did not exist pre-pandemic. In some cases, the activist investor’s thesis may be so detailed as to warrant presenting the company and, possibly other investors, with a lengthy “white paper” laying out in detail the opportunities to unlock value that the activist investor has identified and believes are actionable.

In the context of an activist campaign at a closed-end fund, the presentation of a white paper would not be likely since the activist investor’s investment thesis is not generally subject to much variation or nuance. While an activist investor may include in its communications with the fund’s shareholders some criticisms of the fund’s board and/or management, governance, and/or fund performance relative to peers as it looks to apply public pressure to the fund and build shareholder support for its activism campaign, it is generally not the case that an activist investor targeting a closed-end fund has an investment thesis that is tied to improving the fund’s board and/or management, governance, or ability to execute on its stated investment objective. More likely, an activist investor targeting a closed-end fund is generally focused on only one path to unlock shareholder value: causing the fund to pursue a liquidity event, such as a self-tender offer, that allows the activist investor to monetize the discount between the closed-end fund’s share trading price and its per-share NAV.

M&A Is Not a Common Activist Investor Demand of a Closed-End Fund, Though, in Theory, It Is a Potential Path to Unlock the NAV Discount

M&A is a frequent demand made by activist investors at operating companies. Even if an activist investor does not make M&A the cornerstone of its activism campaign against an operating company and makes board changes its primary demand, the activist investor’s ultimate endgame for unlocking shareholder value is often a sale of the company, a carve-out, or another M&A transaction.

In the context of activism campaigns at closed-end funds, M&A is not typically a demand made by the activist investor. As noted above, the activist investor targeting a closed-end fund is generally singularly focused on having the fund pursue a liquidity event that allows the activist investor to monetize the discount between the fund’s share trading price and its per-share NAV. While, in theory combining the targeted closed-end fund with another fund may be a path to monetize the NAV discount, it is more typical for the activist investor to push for the fund to commit to a self-tender offer for a significant percentage of the fund’s issued and outstanding shares at a price very close to NAV.

Activist Investors at Closed-End Funds Are Ultimately Less Concerned About Causing the Fund to Implement Board, Investment Advisory, and Governance Changes If They Can Get the Fund to Unlock Its NAV Discount

In the context of a settlement of an activist campaign between an activist investor and an operating company, it would generally be the case that the settlement would provide for some change to the company’s board of directors, particularly where the activist investor had previously proposed nominees or otherwise called for changes to the company’s board. The settlement may also provide for some governance changes where such changes were previously proposed by the activist investor. In addition, from time to time, we also see settlements that may require the company to take specific actions intended to enhance the company’s ability to grow shareholder value.

In the context of a settlement of an activist campaign between an activist investor and a closed-end fund, it is not uncommon for a settlement between the fund and the activist investor to not result in any changes in the fund’s board membership, investment adviser, and/or governance practices, even where the activist investor had previously and publicly proposed nominees to the fund’s board, termination of the fund’s investment adviser, and/or changes to the fund’s governance practices such as a de-staggering of the board. Settlements between an activist investor and a closed-end fund tend to be primarily focused on having the fund commit to one or more actions that would effect, in the near term, a liquidity event that will unlock the fund’s NAV discount, which may include a self-tender offer, a self-tender offer in combination with a managed distribution program, or a termination of the fund in order to effect a liquidating distribution.

Why an Activist Investor Would Target a Closed-End Fund

In deciding whether to target a particular closed-end fund, an activist investor would generally consider one or more of the following factors:

- Existence of a significant discount between the fund’s share trading price and its per-share NAV

- Ability of the activist investor to accumulate a significant stake in the fund

- Opportunity for the activist investor to monetize the discount between the fund’s share trading price and its per-share NAV within a relatively short period of time by compelling the fund to pursue a liquidity event

- That other shareholders will welcome the activist investor’s agitation against the fund and would be willing to support the activist investor if the activist investor were to wage a proxy contest against the fund

- That the fund has few tools to deploy in its defense against the activist investor and is vulnerable to an activist campaign

- That the activist investor may be able to avoid a proxy contest and get the fund to agree to a negotiated settlement pursuant to which the fund would commit to causing a liquidity event to occur within a time horizon acceptable to the activist investor

- That, if the activist investor had to wage a proxy contest all the way to a shareholder vote, it would have a reasonable likelihood of prevailing against the fund on at least one of its proposals

Possible Activist Investor Demands at Closed-End Funds

The demands that an activist investor may make at a closed-end fund need to be looked at in two tranches. The first tranche of demands are those that may be included in the activist investor’s advance notice of nominations and proposals and proxy statement, but may generally only be means to an end, rather than the actual ends sought by the activist investor. Included within this first tranche may be one or more of the following demands:

- Replacing the fund’s incumbent trustees/directors with the activist investor’s nominees

- Terminating the fund’s investment adviser (and, at times, without proposing a replacement investment adviser), even if such termination would leave the fund “orphaned” with no investment adviser

- Preventing a fund’s investment advisory agreement and/or sub-advisory agreement from being approved by shareholders

- Changing governance practices (e.g., de-staggering of the board)

As discussed above, the activist investor may be limited in what it can propose as part of its campaign against the fund to only those matters that the declaration of trust or other charter document allows shareholders to vote on. As also discussed above, a fund cannot prevent shareholders from voting on the termination or approval of the fund’s investment adviser, so a proposal to terminate the fund’s investment adviser may be made as a means to apply pressure on the fund and its investment adviser, even if it does nothing to directly further the economic objectives of the activist investor.

The second tranche of demands are those that ultimately allow the activist investor to achieve its primary objective of monetizing the discount between the fund’s trading price and its NAV within a time horizon acceptable to the activist investor, and may include one or more of the following demands:

- Self-tender for some percentage of the fund’s shares (e.g., 15% to 50%) at a price close to NAV (e.g., 98.5% to 99.5% of NAV)

- Termination of the fund to effect a liquidating distribution

- Open-end conversion of the fund

- Merger of the fund with another fund

- Managed distribution program for an agreed-upon period of time

What Makes a Closed-End Fund Vulnerable to an Activist Investor

An activist investor does not target a closed-end fund just because the fund is vulnerable. An activist investor must first determine (1) that there is an opportunity to generate an outsized return because the fund is undervalued by the financial markets relative to its intrinsic value, which generally means that the fund’s shares are trading at a significant discount to its NAV, and (2) that there is a path for the activist investor to unlock the NAV discount within a time horizon that is acceptable to the activist investor. If a fund meets those two criteria, it may be an attractive target for an activist investor. Thereafter, the activist investor needs to determine how vulnerable the fund is to an activism campaign.

In the wake of COVID-19, the following are some of the key ways that a fund could be vulnerable to an activist investor seeking to wage a proxy contest or other activism campaign to pressure the fund to pursue a liquidity event that monetizes the NAV discount:

- Poor fund performance, relative to its peers

- Persistent and significant discount between the fund’s trading price and its NAV, particularly when compared to peers

- Opportunity for the activist investor to monetize the discount between the fund’s share trading price and its per-share NAV within a relatively short period of time by compelling the fund to pursue a liquidity event

- Failure of the fund to explain what actions it is taking to improve fund performance

- Failure of the fund to explain what actions it is taking to mitigate the discount between the fund’s trading price and its NAV

- Lack of confidence by investors in the ability of the fund’s board and/or management to improve fund performance and/or mitigate the discount between the fund’s trading price and its NAV

- Failure of the fund to prepare for an activist investor and the various types of demands it could make on the fund

- Ability of the activist investor to acquire a significant stake in the fund and no practicable ability of the fund to impede or prevent the activist investor from acquiring such a stake

Steps for a Closed-End Fund to Take to Avoid Being a ‘Sitting Duck’ for an Activist Investor

It is possible that the success that activist investors had during 2020, in the wake of the COVID-19 market dislocations, in pursuing proxy contests and other activism campaigns at closed-end funds, and in driving the monetization of the funds’ NAV discounts may encourage more activism campaigns against closed-end funds, including by activist investors that heretofore have not targeted closed-end funds. It is also possible that the experiences of the numerous closed-end funds that had to respond to campaigns waged by activist investors in 2020, and the concessions that some of these funds agreed to make to avoid costly and distracting activism campaigns—including agreeing to a liquidity event to facilitate the monetization of the NAV discount sought by the activist investor—may be a “wakeup call” that closed-end funds need to more actively and regularly prepare for shareholder activism in a manner more akin to the approach taken by larger publicly traded operating companies. Accordingly, closed-end funds looking to prepare themselves for the possibility that they will be targeted by one or more activist investors, whether during the 2021 proxy season or thereafter, should consider taking the following actions:

- Assemble an activism response team (e.g., counsel, proxy solicitor, public relations firm)

- Enhance processes to receive early warning of an activist investor targeting the fund (e.g., stock watch, activist investors attending earnings calls, market rumors, media inquiries, SEC filings on Form 13F, Schedule 13G, and Schedule 13D)

- Review and analyze the fund’s shareholder profile on a regular basis

- Identify any activist investors that could be potentially interested in targeting the fund (e.g., activist investors that regularly target closed-end funds)

- Monitor activism campaigns against other funds, particularly the fund’s peers

- Conduct a comprehensive assessment of the fund’s vulnerabilities to an activist investor

- Consider enhancing the fund’s bylaws, particularly provisions relating to advance notices of nominations and shareholder proposals

- If the fund is organized as a trust, consider whether the declaration of trust and bylaws of the fund sufficiently take advantage of the flexibility provided by the applicable state’s trust statute rather than simply mirroring charter and bylaws provisions originally developed for a corporation subject to a state’s corporations statute

- Consider having a ”shelf” poison pill prepared that has been adapted to the special requirements of the 1940 Act and vetted with the fund’s board, and which is ready to be adopted and implemented on short notice

- Consider opting into a control share acquisition statute, taking into consideration the updated guidance related thereto provided by the staff of the SEC Division of Investment Management as well as the related updated ISS proxy voting guidelines, or, if the fund’s state of organization does not have a control share acquisition statute, consider re-domiciling the fund in a state that has a control share acquisition statute

- Develop and maintain a timetable of key fund events and deadlines, including for the receipt of advance notices of nominations and shareholder proposals as well as the latest date by which the fund needs to hold its annual meeting in accordance with its governing documents and/or state law

- Know all the obvious paths to mitigating the discount between the fund’s trading price and its NAV and be prepared to communicate why any of those paths may not be appropriate for the fund to consider pursuing

- Anticipate how an activist investor would criticize the fund and actions the fund has taken or not taken to mitigate the discount between the fund’s trading price and its NAV and be prepared to rebut those criticisms

- Anticipate how an activist investor would criticize how the fund, relative to its peers, fared in response to the COVID-19-driven market dislocations and how the fund, relative to its peers, recovered

- Be prepared to communicate why the fund should not be taking actions that an activist investor may demand (e.g., tendering for the fund’s shares at a price close to NAV, terminating the fund, open-ending the fund, merging the fund with another fund, or commencing a managed distribution program)

- Become familiar with the possible proposals that an activist investor targeting the fund would likely make, taking into consideration whatever applicable limitations are contained in the fund’s declaration of trust and/or bylaws

- Knowing that termination of the fund’s investment advisor is an easy and obvious proposal for the activist investor to submit as part of its activism campaign against the fund, be prepared to communicate why the fund’s investment adviser should retain its role and why such a proposal is not in the best interests of the fund’s shareholders

- Develop a “break-glass” plan for responding to an activist investor targeting the fund

- Plan today for how the fund would engage with an activist investor targeting the fund and who from the fund’s board and/or management would participate in such engagement

- Refine strategic communications to hone key messages on how the fund has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and what steps the fund is taking to mitigate the discount between the fund’s trading price and its NAV

- Plan investor outreach to assess investor sentiment, gather intelligence, and gain feedback on the fund’s performance and execution of its investment objectives, including how the fund performed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic relative to its peers

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print