Matteo Tonello is Managing Director of ESG Research at The Conference Board, Inc. This post relates to CEO Succession Practices in the Russell 3000 and S&P 500: 2020 Edition, an annual benchmarking study and online dashboard published by The Conference Board, with Professor Jason Schloetzer of the McDonough School of Business at Georgetown University, and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in collaboration executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles.

CEO Succession Practices in the Russell 3000 and S&P 500: 2020 Edition provides a comprehensive set of benchmarking data and analysis on CEO turnover to support boards of directors and executives in the fulfillment of their succession planning and leadership development responsibilities.

The study reviews succession event announcements about chief executive officers made at Russell 3000 and S&P 500 companies in 2019 and, for the S&P 500, the previous 18 years. To provide a preliminary assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on top leadership changes, this edition is also supplemented with data on CEO succession announcements made in the Russell 3000 in the first six months of 2020.

The project is conducted by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in collaboration with executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles. An online dashboard with data visualizations by business sectors and company size groups is available here.

Drawn from such a review, the following are the key findings and insights.

CEO turnover in the Russell 3000 dropped in the second quarter of 2020 as boards opted for leadership continuity to manage the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout have been of historic proportions. Since the first lockdown measures were implemented in the United States, boards and top management teams across the Russell 3000 have worked hard to navigate the implications of the crisis on the liquidity and financial stability of their companies, the health and well-being of their employees, and the purchasing behaviors of their customers.

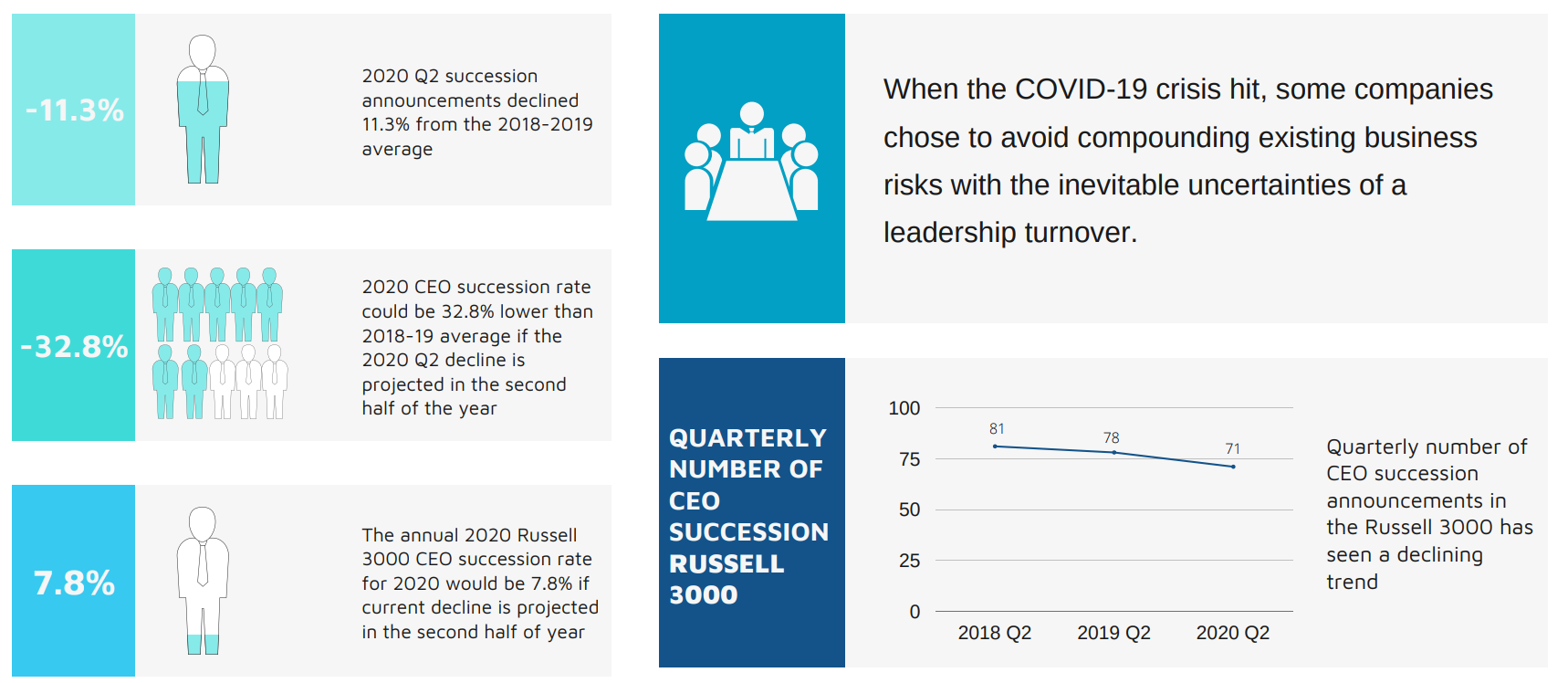

CEO succession is one of the most consequential events a company may face, with possible profound effects on its strategy, its organizational culture, and its relationship with investors and other stakeholders. Therefore, it is not entirely surprising to find that, when the COVID-19 crisis suddenly disrupted business activities in the United States in mid-March 2020, some companies chose to avoid compounding existing business risks with the inevitable uncertainties of a leadership turnover.

Our data show that, while the Russell 3000 CEO succession rate for the first quarter of 2020 was substantially similar to those recorded for the same periods of 2018 and 2019, it dropped significantly in the second quarter. Specifically, in the April 1–June 30, 2020 period, Russell 3000 companies counted only 71 CEO succession announcements—a decline of 11.3 percent from the average number of 80 CEO turnovers reported in the second quarters of 2018 and 2019.

While it is difficult to predict the future in the midst of a global health crisis, if we were to project the 11.3 percent decline into the second half of 2020, the annual Russell 3000 CEO succession rate for all of 2020 would be 7.8 percent, or 32.8 percent lower than the average annual rate of 11.6 percent reported for the 2018–2019 years.

There is also evidence that boards of directors that moved forward with their CEO succession plans have been opting for permanent replacements rather than interim CEOs. This seems a sign of their preference for a strong leadership mandate for the new CEO rather than a transitional role at a time when the workforce and the market seek reassurance about the company’s ability to fully recover from the crisis and set a future course. In particular, the rate of interim CEO appointments in the first half of 2020 was 18.1 percent, down over 3 percentage points from the average annual rate of 21.4 percent recently measured for 2018 and 2019.

What’s ahead? The COVID-19 pandemic continues to wreak havoc on the US job market. Despite recent improvements, unemployment remains close to double digits and job creation well below prepandemic levels. This adverse situation puts CEO performance to the test. As hard as it is to make a prediction, the rate of CEO succession may accelerate as we enter 2021. At some companies, boards may revisit long-term business objectives and conclude that new leadership is needed. Others may conclude that the crisis offers an opportunity to revisit board leadership and add a non-executive chairman to strengthen management and avoid the upheaval and discontinuity resulting from a hasty CEO turnover event. Others may find that the crisis has highlighted gaps in the existing executive leadership, such as the need for stronger communication skills. Some CEOs may also choose to retire after leading the company through such a challenging time. For all of these reasons, The Conference Board, ESGAUGE, and Heidrick & Struggles will continue to update the dashboard in early 2021 and throughout next year.

The crisis is also an opportunity for boards of directors to continue to strengthen their planning process on CEO turnover and leadership development. Crisis preparedness practices, in particular, suggest that companies should complement their regular succession process with ready-to-go, emergency succession plans—for the CEO and other critical senior roles. In particular, in a volatile business environment subject to the unpredictability of the pandemic, boards and appropriate committees should reserve time to conduct the following emergency planning activities:

- a) revisit the job description of the CEO and other key functions in light of the most pressing organizational needs, which may differ not only from those mapped in regular circumstances but also from those the board had anticipated only a few months before, at an earlier stage of the crisis;

- b) review the short list of candidates who meet the updated job requirements to ensure that, for any key roles, a successor or interim successor is ready to step in without any material loss of continuity in organizational leadership;

- c) conduct scenario exercises meant to test the organization’s preparedness to marshal the resources needed in the implementation of a sudden turnover;

- d) solicit updates on the effectiveness of the safety protocols adopted by the organization and the health of its employees;

- e) define a communication strategy meant to inform and reassure the workforce and other key stakeholders.

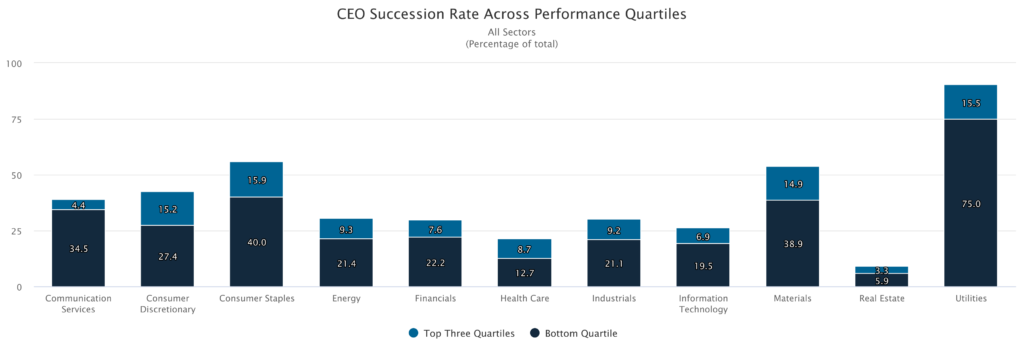

Underperforming consumer staples companies reported a CEO succession rate of almost 40 percent, and CEO turnovers at larger companies in the S&P 500 have been rising in recent years. These trends could become even more pronounced in the uncertain times ahead.

Company performance continues to be a main driver of business leadership turnover. Over the years, our data have consistently highlighted meaningful differences in the rates of CEO succession between better-performing and worse-performing companies. In the Russell 3000, the average 2019 rate of CEO succession was 9.4 percent for better-performing companies and 19.4 percent for worse-performing companies. For S&P 500 companies, the rates were 11.3 percent and 20.2 percent for better-performing and worse-performing companies, respectively. Moreover, CEO successions at worse-performing companies in the S&P 500 have been trending upward: while the average rate for the 15-year period from 2001 to 2015 was 13.7 percent, it increased to 18 percent in the period from 2016 to 2019.

These differences are further accentuated in the business sector analysis. In particular, worse-performing consumer staples and utilities companies in the Russell 3000 reported significantly higher rates of CEO succession (40 and 75 percent, respectively) than the one found among worse-performing real estate companies (5.9 percent). Ownership structures and the need to set a new strategic course in certain business industries may help to explain these wide gaps.

What’s ahead? While underlying stock performance continues to be the main driver of turnover, in today’s era of stakeholder capitalism (which many CEOs embrace), business leaders are expected to balance the demands of multiple constituents (e.g., investors, customers, employees, suppliers, and communities) while creating durable shareholder value. This means not only that the CEOs at financially underperforming companies may come under scrutiny by a broader array of stakeholders, but also that CEO performance in serving multiple stakeholders can increasingly be a cause for leadership change. When evaluating performance, directors take into account factors beyond the control of senior management, including the cyclicality of the business, the competitive landscape, and adverse macroeconomic circumstances. However, the increased public scrutiny and additional demands placed on CEOs may make it even more difficult for boards to retain an underperformer.

While boards remain vigilant in assessing shifting customer interests and rapidly changing business environments, they should exercise equal care in evaluating the leadership pipeline. CEO succession planning should be an agenda item during strategic discussions and should remain, along with talent management strategies, integrated into business performance reviews rather than placed as a separate agenda item that is reviewed annually. One way to accomplish this is by developing a strategic leadership profile, which creates a natural bridge from the discussion of company strategy to succession planning by identifying the skills, experiences, and personal attributes that the CEO of the future will require in order for the company to achieve its strategic goals. If the rate of CEO succession continues to trend upward in the coming years, as shown in particular among the worst performers in the S&P 500, more boards will face the need to navigate a leadership change.

After peaking in 2018 amid prominent #MeToo scandals, CEO departures due to personal misconduct have declined. Forced CEO departures are mainly caused by poor company performance, with substantial differences across size groups.

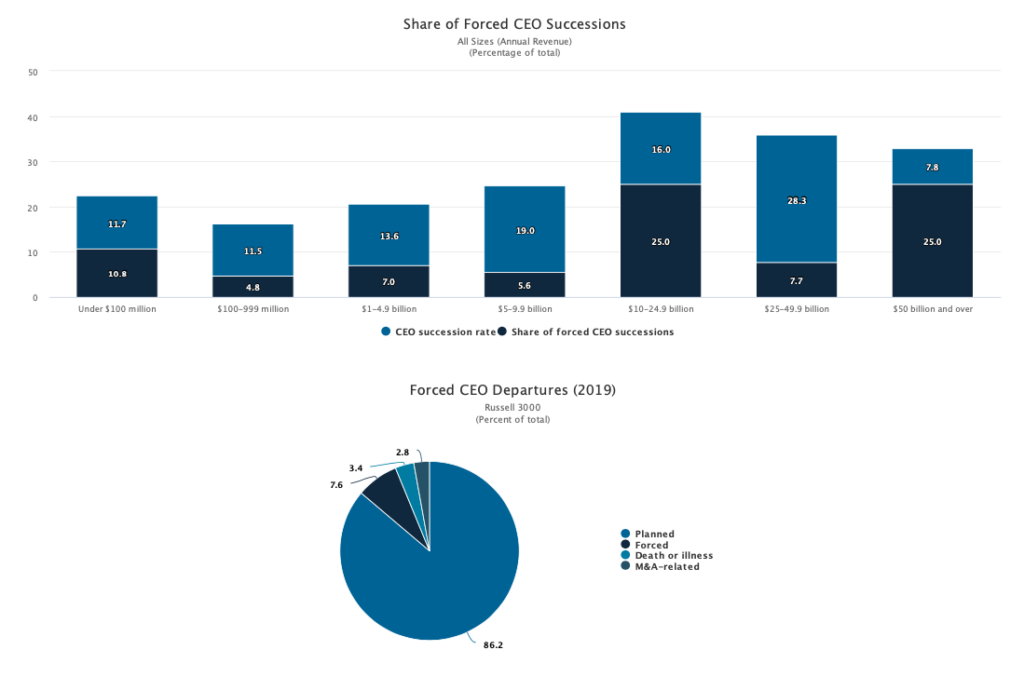

The share of “forced” CEO successions has declined in the last year, in both the Russell 3000 (where 7.6 percent of all succession events announced in 2019 were nonvoluntary, down from 8.6 percent in 2018) and the S&P 500 (with only 14.9 percent of forced CEO successions, down from 17.7 percent in 2018 and 15.5 percent in 2017).

In 2019, in the Russell 3000, the leading causes of forced or unplanned CEO departures were underperformance (59.3 percent of all forced departures), personal misconduct (11.1 percent), and financial misconduct (7.4 percent); the remaining 22.2 percent of forced departures were due to reasons such as a disagreement between the CEO and the board of directors. There is a similar pattern of evidence for the S&P 500, in which the leading causes of forced CEO departures were underperformance (60 percent of forced departures) and personal misconduct (20 percent); there were no forced departures due to financial misconduct in 2019, and the remaining 20 percent of unplanned departures were for other reasons.

The year-on-year analysis reveals a steep decline in the number of forced CEO departures due to personal misconduct, in both the Russell 3000 and S&P 500. Among Russell 3000 companies, forced departures due to personal misconduct declined from 44.8 percent of the total number of forced departures in 2018 to 11.1 percent in 2019. Similarly, among S&P 500 companies, personal misconduct cases conducive to CEO departures declined from 54.5 percent of the total number of forced departures in 2018 to 20 percent in 2019. Across business sectors, the consumer discretionary and health care sectors were the only two sectors to report forced CEO departures due to personal misconduct in 2019, while financials and information technology were the only two sectors that reported forced CEO departures due to financial misconduct.

Overall, the share of forced CEO successions among S&P 500 companies is twice as high as that of the Russell 3000 (as mentioned above, 14.9 percent versus 7.6 percent, respectively, in 2019). The size analysis conducted across the Russell 3000 is even more telling: in 2019, 25 percent of all CEO successions announced in the group of companies with annual revenue of $50 billion and higher and with annual revenue between $10 billion and 24.9 billion were forced, compared to only 10.8 percent of those announced by companies with annual revenue under $100 million and 4.8 percent of those announced by companies with annual revenue in the $100 million–$999 million group.

What’s ahead? It is well known that a healthy corporate culture has a positive correlation with company performance. The #MeToo movement against sexual harassment resonated profoundly within the business community and motivated employees to speak up about situations of personal misconduct they have experienced or witnessed in the workplace. This has provided boards of directors with new insights into the private behaviors of top management. And, at times, boards found themselves needing to take action. These types of scandals bear a tremendous business risk, well beyond the immediate financial costs, with reputational repercussions that may reverberate for years.

The substantial decline in forced CEO succession events due to personal misconduct is both heartening and concerning: heartening if it is an indication that a cultural shift has indeed taken place and those in a position of authority now understand that their abuse of power will no longer be tolerated, but concerning if it means that, after the media attention has abated, companies have reverted to a situation where employees may again feel anxious about speaking up.

It may take some time to sort out the factors at play here—and the impact that the focus on racial equality in the wake of George Floyd, and not just gender equality, has on CEO turnover. It does seem clear, however, that the focus on leadership by example will continue. For this reason, boards and top management should continue their support for robust corporate policies where instances of misconduct—at any level of the company—are followed by swift disciplinary action so that anyone feels emboldened to speak up. These practices should include:

- Stating a clear commitment from the top to eradicate intolerance and abuse and promote a safe environment where employees can count on each other and on the upper ranks of the organization to respond to wrongdoing. Tone at the top is crucial to build trust and set an example for everyone.

- Codifying and internally communicating a protocol for those on the receiving end of a situation of abuse of authority to file complaints without fear of retaliation (and for third parties to report inappropriate interactions they may have witnessed). Information obtained through a hotline or other reporting channels should rigorously be anonymized and elevated, including (in the appropriate actionable format) to the board of directors. It is also important that the human resources department or whoever takes the lead in handling these complaints be perceived by employees as a safe and trusted place. As recently as March 2020, a widely publicized survey revealed the distrust employees still have for their HR department.

- Ensuring full collaboration among key departments. Complaints about employee misconduct can sometimes be “siloed” within the internal human resources, employment law, or compliance functions. Moreover, unlike for reports of financial misconduct, which are typically handled by the compliance function and reported to the board’s audit committee, companies may not have consistent and robust processes for reporting discriminatory misconduct to the board. It’s important to ensure that the internal compliance, human resources, and employment law functions work in tandem on these matters, which should be appropriately reported to one or more board committees.

- Conducting a periodic assessment of corporate culture. In addition to receiving incident reports as noted above, the board or its committees should be provided with periodic reports of key human capital management metrics (on employee satisfaction and engagement, diversity and inclusion, talent acquisition and retention, and pay equity within the workforce, among others) that enable it to evaluate corporate culture and the likelihood that an occurrence of personal misconduct may occur.

- Adding language to employment contracts to discourage personal misconduct. Termination clauses, in particular, should explicitly define “cause” to prevent severance payments or stock vesting in instances of misconduct.

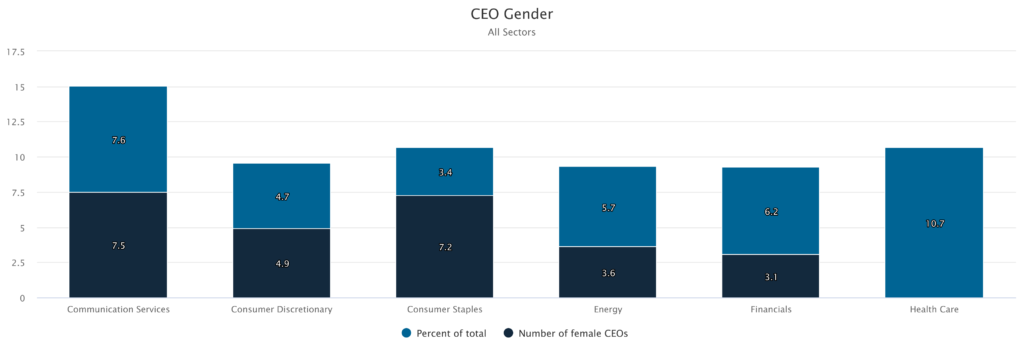

Women represent only about 5 percent of sitting CEOs in each index. While the percentage of incoming female CEOs has been growing in recent years, so has their rate of departure, which in 2019 was higher than the 18-year average. Female CEOs are more likely to be found at smaller companies and less likely in IT, financial services, and real estate sectors.

Women represent approximately 5.4 percent of sitting CEOs among companies in both the Russell 3000 (162 female CEOs) and S&P 500 indexes (27 female CEOs). This percentage has been similar from 2017 through 2019. While it is common to read about the dearth of women among the highest ranks of corporate America, less attention has been given to the characteristics of the companies that women currently lead. Yet those companies could offer valuable lessons on how to steer progress in female and other minority representation in business leadership. Our comprehensive Russell 3000 analysis of business sectors and company size groups helps us to shed more light on these traits.

Real estate, financials, and information technology companies report the lowest percentage of women CEOs (3.1 percent, 3.4 percent, and 3.6 percent, respectively). Utilities (10.7 percent), communication services (7.6 percent), and consumer discretionary companies (7.5 percent) have the highest. Fran Horowitz of Abercrombie & Fitch, Mary Barra of General Motors, Lynn Good of Duke Energy Corporation, Julia Hartz of Eventbrite, and Shar Dubey of Match Group are some of the women on the list of female Russell 3000 CEOs in these industries.

The analysis by company size provides further insights. Most female CEOs are found at manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies with annual revenue of less than $4.9 billion (specifically, 107 of 137 female CEOs of manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies in the Russell 3000, or 78.1 percent). Among real estate and financial firms, most female CEOs lead companies with asset values between $1 billion and $9.9 billion (16 of 25 female CEOs of real estate and financial companies in the Russell 3000, or 68 percent). Of the 122 real estate and financial firms with asset values greater than $25 billion, only five are led by a woman (or 4 percent of the companies in this size group).

While figures on the gender of incoming CEOs are encouraging, they are in fact countered by findings on CEO departures. Together, these sets of numbers explain why progress across indexes continues to be remarkably slow. Among the Russell 3000, 8.2 percent of incoming CEOs were women, an increase from the 8 percent of 2018 and the 4.3 percent of 2017. Among the S&P 500, 10.4 percent of incoming CEOs were women, a significant increase from the 18-year rate of women CEO appointments of 5.8 percent from 2001 to 2018, and the third highest rate of incoming female CEOs in the entire 19-year historical period tracked by this study.

However, approximately 6.2 percent of 2019 CEO departures in the Russell 3000 were women, and they also increased from the 4.1 percent found in 2018 and the 3 percent of 2017. Women also represented 6 percent of 2019 CEO departures among the S&P 500, which is alarmingly higher than the 18-year departure rate of 3.7 percent from 2001 to 2018. Ultimately, among the Russell 3000, there was a net increase of seven female CEOs from 2018 to 2019, based on 29 incoming and 22 departing female CEOs. In the S&P 500, there was a net increase of three female CEOs from 2018 to 2019, based on seven incoming and four departing female CEOs.

What’s ahead? The growing pressure from the investment community and other stakeholders to accelerate progress on workforce and management diversity is not going to abate anytime soon. In fact, the public calls for racial justice that followed the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020 have further invigorated actors who have been committed to the corporate diversity cause for years.

- In August 2020, State Street Global Advisor sent a letter to all board chairs of public companies in its investment portfolio stating that it expects “specific communications” to shareholders regarding, among other things, the role of diversity in the company’s human capital management practices and strategy, measures of diversity of the company’s global employee base, future diversity goals, and the description of the role the board is expected to perform in overseeing diversity and inclusion.

- Legislative and regulatory initiatives are underway, at the federal and state levels, to mandate corporate disclosure of board and workforce diversity. Most recently, after the 2018 mandate for corporate boards to meet specific quotas for female directors, California approved a new law extending the quota approach to the representation of other minority groups. Similar laws, whether instituting diversity quotas or requiring additional disclosures, were adopted in the states of New York, Illinois, and Washington, while two bills setting new diversity disclosure requirements for all publicly traded companies are advancing in the US Congress.

- In August 2020, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) amended Regulation S-K Disclosure to require additional disclosure regarding human capital resources, including any material human capital measure or objective on which the company focuses in managing its business. While the provisions are broadly defined, they will expose companies to additional investor scrutiny.

- In late September 2020, the Office of the New York City Comptroller issued a news release indicating that, in response to a letter that had been sent to S&P 100 CEOs earlier in the summer, nearly half of the companies in the index had committed to publicly disclosing the information on their workforce demographics that they annually report to the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The office also indicated that it would target directors of companies that did not comply with its request and vote against their reelection.

- Sustainability disclosure standards, such as those set by the Global Reporting Institute (GRI) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), extend to human capital practices and are gaining in prominence among US issuers. According to the most recent edition of The Conference Board Sustainability Practices Dashboard, 51 percent of the 250 largest US public companies by annual revenue disclose using GRI guidelines in their CSR reports, up from the 45 percent recorded in the prior year. As of June 2020, 215 US public companies had adopted SASB-compliant sustainability reporting (often augmenting them with additional metrics under GRI guidelines).

We expect boards of directors and senior executives to step up their commitment to bringing racial and ethnic diversity, not only gender diversity, to the front and center of leadership development programs. There is extensive literature, including from The Conference Board, on how business organizations can advance diversity, equity, and inclusion, from the lower ranks of the workforce to top management. In general, companies that are succeeding at this task are embracing modern technologies and taking a holistic approach to redesigning internal practices—ranging from talent sourcing and selection to establishing equity KPIs meant to surface gaps and vulnerabilities, and from better understanding employee experience to supporting learning and development opportunities.

It should also be noted that CEO diversity does not depend only on programs focused on management; board diversity can also play a role. We are seeing that, increasingly, companies choose to draw their new CEOs from their board of directors (see our finding on page X). Therefore, as boards become more diverse, so may the population of CEOs who come from boards. Moreover, more diverse boards will bring access to new “networks” of leading talent for consideration, further increasing the diversity of the CEO population.

Other notable findings

On CEO age

The average departing CEO in both indexes is about 60 years old and has been in the position for seven years. In the S&P 500, the average age of departing CEOs is 60.2 years, or identical to the average measured for the entire historical period since 2001 for which The Conference Board and ESGAUGE have collected annual data. In the Russell 3000, the average departing CEO age is only slightly lower, or 59.5 years of age. The Russell 3000 analysis by business sectors shows a somewhat wider range, from the highest average departing CEO age calculated among companies in the real estate and financials sectors (61.9 and 61.6 years of age, respectively) to the lowest recorded among companies in the consumer discretionary and consumer staples sectors (57.6 and 57.5 years of age, respectively).

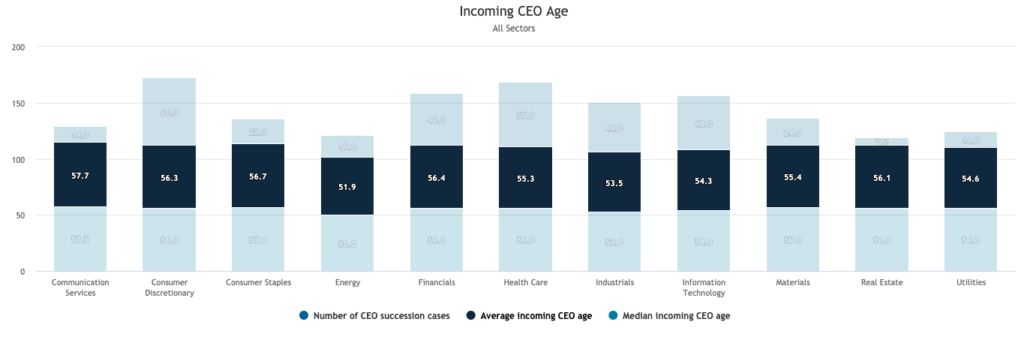

It’s still good to be in your 50s if you want to become a CEO, but the average incoming CEO in the S&P 500 is somewhat older than historical trends, and there is a wide average age variation between small and large financial companies. The average age of an incoming CEO in the Russell 3000 was 55.3 years in 2019, in line with the average age of 54.5 years and 54.6 years calculated for 2018 and 2017, respectively. In the S&P 500, incoming CEOs in 2019 were 54.6 years old, which is somewhat higher than the 53.2 years found on average for the entire historical period since 2001 for which The Conference Board and ESGAUGE have collected annual data. Across business sectors, the oldest incoming CEOs are seen in the communication services and consumer staples sectors (57.7 years and 56.7 years, on average, respectively), while the youngest are in the energy and industrials sectors (51.9 years and 53.5 years, on average, respectively). Among manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies in the Russell 3000, the average incoming CEO age was remarkably similar across revenue size groups. By contrast, among real estate and financial companies, the average incoming CEO age among companies with asset values between $500 million and $999 million was 10.3 years younger than the average age of an incoming CEO among companies with asset values greater than $100 billion (49.5 years and 59.8 years, respectively).

The Russell 3000 has more CEOs who are 65 or older than under 50, with the oldest in the real estate and financials sectors. The average age of a sitting CEO is 57.7 for companies in the Russell 3000 and 58.6 for the S&P 500. Across business sectors, the average age of a sitting CEO ranges from 56.1 years for information technology companies to 59.4 years for financial companies. Among manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies in the Russell 3000, the average age of a sitting CEO ranges from 56.2 years for smaller companies (annual revenue under $100 million) to 59 years for larger companies ($50 billion and higher). Among real estate and financial organizations, the average age of a sitting CEO ranges from 57.6 years for companies with asset value in the $500 million–999 million group to 61.8 years for the largest companies with assets valued at $100 billion and higher.

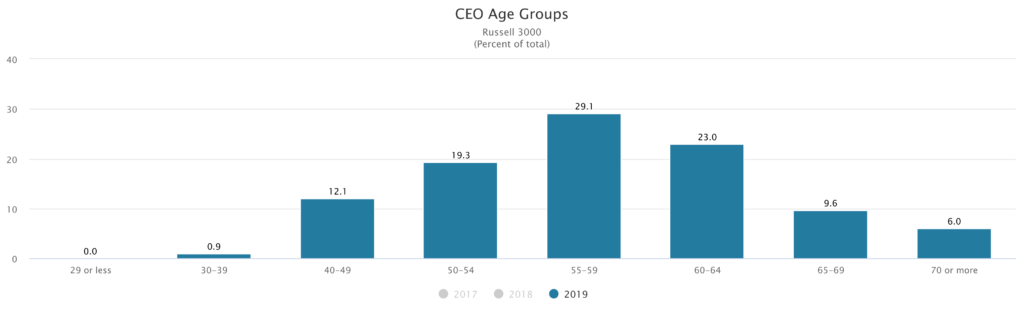

There are far more CEOs in their 70s than CEOs in their 40s, including in the larger Russell 3000. The largest proportion of sitting CEOs in the Russell 3000 and S&P 500 are between the ages of 55 and 59 (29.1 percent and 33.7 percent, respectively). There are significantly more sitting CEOs who are 70 or older (6 percent in the Russell 3000 and 4.8 percent in the S&P 500) than sitting CEOs who are under 40 (0.9 percent in the Russell 3000 and 0.4 percent in the S&P 500), and there are more sitting CEOs who are 65 or older (15.7 percent in the Russell 3000 and 14.1 percent in the S&P 500) than sitting CEOs who are under 50 (13 percent in the Russell 3000 and 6.8 percent in the S&P 500).

While the information technology sector is often portrayed as employing younger executives, the average CEO at an IT company is only 1.6 years younger than the typical CEO in the Russell 3000. Despite the perception that younger generations of business leaders may find more opportunities in the information technology sector, the average information technology CEO is 56.1 years old, or only 1.6 years younger than the typical Russell 3000 CEO.

On CEO tenure

Departing CEOs are serving in the role for fewer years, and their tenure in the S&P 500 is its shortest since 2009. In the Russell 3000, the average tenure of a departing CEO was 6.9 years, which reflects a decline from 9.3 years in 2017. This decline was also detected in the S&P 500, where the average departing CEO tenure of 7.8 years is the shortest tenure for departing CEOs found since 2010 (when it was 7.7 years) and represents a sharp decline from the 10.8 years reported for 2015.

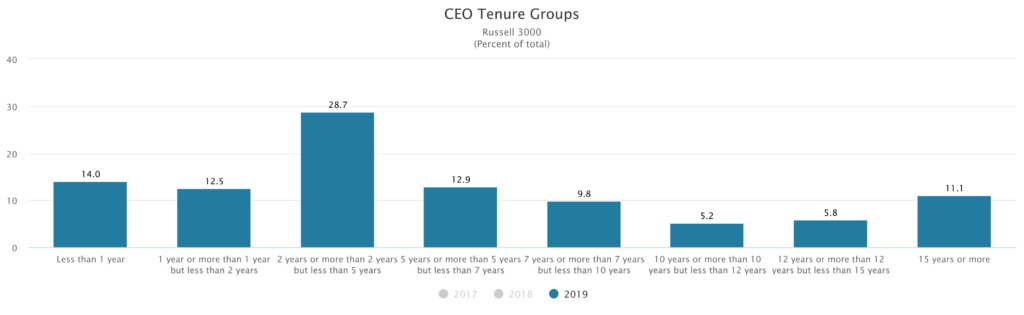

More than 10 percent of sitting CEOs in the Russell 3000 have been on the job for 15 years or longer. Of CEOs in the Russell 3000, 11.1 percent have a tenure of 15 years or longer. In comparison, 9.8 percent of CEOs have a tenure of seven years or more than seven years but less than 10 years; 5.2 percent have a tenure of 10 years or more than 10 years but less than 12 years; and 5.8 percent have a tenure of 12 years or more than 12 years but less than 15 years. The highest percentage of sitting CEOs with a tenure of 15 years or longer is found in the communication services sector (15.1 percent), while the lowest is in utilities (2.7 percent). Nearly a quarter (23.8 percent) of financial and real estate companies with asset values of $500 million or less have a tenure of 15 years or longer—the highest percentage seen across the company size analysis. In the S&P 500, the percentage of sitting CEOs with a tenure of 15 years or longer is lower than in the Russell 3000—or 8.2 percent.

On the sources of CEO talent

Cases of companies that choose to appoint a non-executive director as their next CEO are on the rise. Non-executive directors have become a significant source of CEO talent, representing 20.8 percent of insider CEO appointments among the Russell 3000 in 2019. The rate is higher than the 16.4 percent rate found in 2017 and the 18.9 percent rate of 2018. Among the S&P 500, 14.8 percent of insider CEO appointments were serving as non-executive directors at the company—up from 10 percent and 14.3 percent in 2018 and 2017, respectively. The practice of appointing a non-executive director to the CEO role is particularly prominent among smaller companies: 38.9 percent of inside CEO promotions at manufacturing and nonfinancial services companies with annual revenue under $100 million involve an individual who had been serving as a non-executive director at the company, compared to only 9.1 percent of those at companies with annual revenue in the $25 billion to $49.9 billion segment.

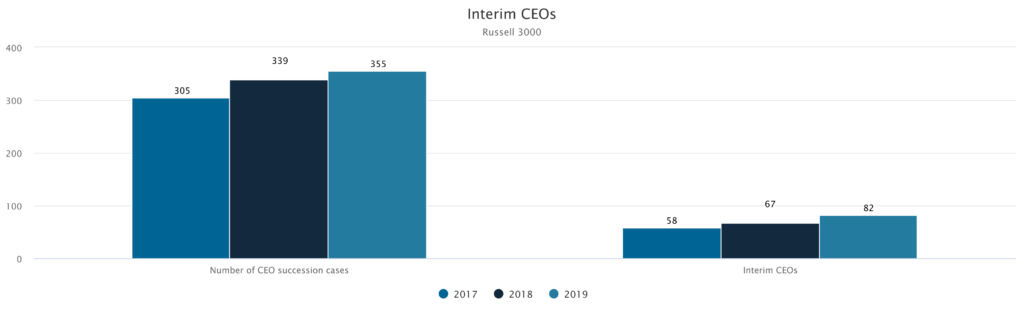

COVID-19 may have partially halted the trend from the first few months of 2019 of companies increasingly choosing to appoint interim CEOs while they conduct a thorough search for the new leadership. We noted above that, during the second quarter of 2020 and at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, companies have generally opted for permanent CEO appointments rather than interim solutions. These data, if confirmed for the rest of 2020, represent a departure from the trend of entrusting a leadership transition to the experienced hands of an interim executive (most often, the board chair or a senior independent director)—a trend The Conference Board had documented over the last few years. In 2019, nearly one-quarter (23.1 percent) of incoming CEOs in the Russell 3000 were appointed as interims—up from the 19 percent rate recorded in 2017 and the 19.8 percent rate of 2018. In the S&P 500, 14.9 percent of incoming CEOs were appointed as interims—up from the six-year average rate of 11.7 percent reported for the index from 2013 to 2018. The proportion of incoming CEOs who were appointed as interims seems comparable across business sectors.

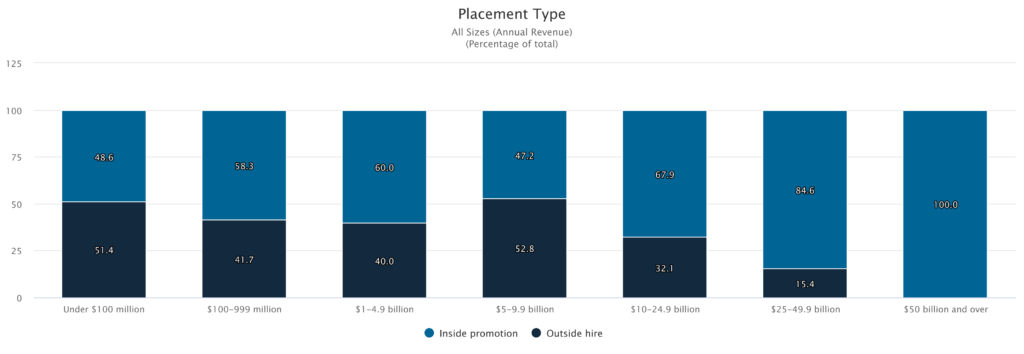

Outsiders being appointed to the CEO position, though not common, continues to be more prevalent among Russell 3000 than S&P 500 companies. In the Russell 3000, 37.7 percent of 2019 incoming CEOs were outsiders, while the remaining 62.3 percent were insiders. These insiders had an average tenure-in-company of 11.4 years in 2019, with 19 percent of them reporting a tenure of more than 20 years with the company. The numbers are lower in the S&P 500, where only 19.4 percent of 2019 incoming CEOs were outsiders, compared to 80.6 percent of insiders. The rate of 80.6 percent is higher than the eight-year rate of insider CEO appointments of 77 percent calculated for the entire 2011–2018 period. These insiders had an average tenure-in-company of 15.7 years in 2019, which is consistent with the 18-year average of 15.5 years from 2001 to 2018. Of the 2019 insider CEOs, 35.2 percent have a tenure of more than 20 years with the company, which is higher than the six-year average rate of 32.7 percent reported from 2013 to 2018.

There are notable differences in the sources of CEO talent across the 11 GICS business sectors. Strategic needs and talent availability in individual industries may explain such divergent numbers. The proportion of insider CEOs who previously served as a non-executive director was highest in the communication services sector (44.4 percent) and lowest among financials (11.1 percent). Real estate and utilities companies reported the highest rate of insider CEO appointments (100 percent and 92.9 percent, respectively), while consumer discretionary and energy companies recorded the lowest (50 percent and 52.6 percent, respectively). The average tenure-in-company of an insider CEO appointment was highest among utilities companies (18.7 years) and lowest among companies in the communication services sector (4.9 years). Overall, the data suggest that senior managers of communication services companies have the fastest inside career track to the chief executive role (64.3 percent of 2019 CEO succession cases were insiders, with an average tenure-in-company of less than five years).

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print