Matteo Tonello is Managing Director of ESG Research at The Conference Board, Inc. This post relates to 2021 Proxy Season Preview and Shareholder Voting Trends (2017-2020), an annual benchmarking study and online dashboard published by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in collaboration with leadership advisory and search firm Russell Reynolds Associates and Rutgers Law School Center for Corporate Law and Governance.

2021 Proxy Season Preview and Shareholder Voting Trends (2017-2020) builds on a comprehensive review of resolutions submitted by investors at Russell 3000 companies to provide insights into the new season of annual general meetings (AGMs). The data and analysis include trends in the number and topics of shareholder proposals, the level of support received by those proposals when put to a vote, and the types of proposal sponsors.

In particular, this post provides insights for what’s ahead in four key areas that promise to be the focus of investor attention in 2021: virtual shareholder meetings, environmental issues, human capital management, and board diversity.

The historical analysis across a large index of companies such as the Russell 3000 helps to plot the trajectory of shareholder demands and to gain helpful insights into the voting season ahead.

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to make virtual shareholder meetings a matter of necessity even in the 2021 proxy season. Many lessons can be learned from the experience of the last year, and companies should ensure they adopt technologies and protocols to safeguard shareholder participation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted economic activities around the world, forcing organizations to rapidly reconsider the way to conduct their business and manage their workforce. These effects have extended to the shareholder voting season in the United States, as lockdowns and other restrictive measures on public gatherings adopted by State and local governments required to either postpone shareholder meetings or hold them virtually.

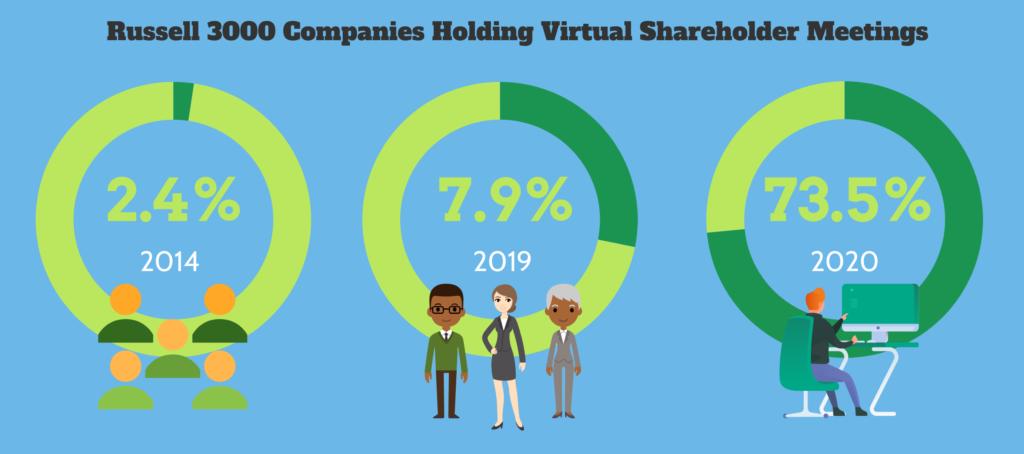

Many companies had been testing virtual shareholder meeting technologies over the last few years, and statistics on the use of this format in lieu of the traditional physical meeting show that it tripled from 2014 to 2019 alone—from 2.4 percent to 7.7 percent of all AGMs in the Russell 3000. But the number of virtual meetings surged during the 2020 voting season to a record level that was unimaginable only a few months before. According to proxy disclosure information tracked by ESGAUGE, as of November 10, only 25 percent of Russell 3000 2020 meetings were held at a physical location and 73.5 percent were moved to an online platform (only 1.2 percent disclosed a hybrid approach, where a physical meeting compliant with rules on social distancing and gatherings was complemented by virtual attendance). The share of 2020 virtual-only meetings in the S&P 500 was even higher (81 percent).

Despite the logistical and technological challenges posed by this monumental shift, the proxy season was successfully executed. Shareholder proposal volume was in line with what The Conference Board and ESGAUGE recorded in prior recent years, and average support level actually inched up among larger companies of the S&P 500 index. The credit goes to the prompt collaboration of the many parties involved in the process—not only companies and investors but also solicitation firms, proxy advisors, regulatory bodies, and the providers of virtual meeting technology. Proxy advisors and institutional investors, traditionally concerned that depriving investors of a physical gathering venue could impair shareholder democracy, recognized the inevitability of the shift to a virtual meeting platform and “the compelling advantages for both companies and shareholders” in the current circumstances. The SEC provided guidance to assist issuers dealing with delays in printing and mailing proxy materials or facing the need to reschedule meetings so that they could be planned for remote attendance. Some States (including New York, New Jersey, California, and Massachusetts) restricting corporations’ ability to hold virtual meetings promptly eased regulations to accommodate these new needs and announced initiatives for legislative reform.

Insights for what’s ahead. Companies should be mindful that the opposition to virtual meetings traditionally shown by some large institutional investors and proxy advisors could resurface when the health crisis ends. In fact, the Council of Institutional Investors (CII), which has generally opposed virtual-only meetings in favor of a hybrid approach where shareholders can choose how to attend, urged companies to “make it clear that this decision is a one-off, tailored for current circumstances.”

Companies should therefore learn from “mass experiment” of virtual shareholder meetings that took place during the 2020 proxy season and apply those lessons as they begin to prepare for the 2021 AGMs. Advance planning is key. In particular, it is important for corporate secretaries and legal departments to:

- Monitor applicable State laws and stock exchange listing standards, and consider updating organizational documents to ensure the company has the latitude it needs to convene virtual meetings, adjourn them, or postpone them—whether in response to the evolution of the pandemic or the technical difficulties experienced in the remote setting.

- Ensure that any technical or administrative shortcoming experienced at the last round of meetings is properly documented, together with the solution (to be) implemented to address it in the future. Technologies continue to evolve as vendors are also rising to the occasion and making use of feedback to improve their platforms.

- Engage with investors to underscore their commitment to shareholder participation and the measures the company has adopted (or intends to adopt) to facilitate the virtual meeting experience—especially during the Q&A session. It is particularly important to ensure clarity in proxy statements and other documents disseminated to shareholders on the procedures that should be followed to attend the meeting and ask questions.

Guidelines for Conducting Virtual Meetings

Companies may find it useful to review guidelines published by the 2020 Multi-Stakeholder Working Group on Practices for Virtual Shareholder Meetings—an initiative involving public companies and investor representatives, including several members of The Conference Board. According to such guidelines, virtual meetings should provide:

- Basic information about the meeting known to the company, which may include a list of attendees, the number of shares represented at the meeting, and preliminary vote counts.

- A live audio and video feed of all key company representatives in attendance, including, at a minimum, the chair, CEO, any lead/presiding director, chairs of key board committees and the corporate secretary.

- A comprehensive Q&A tool allowing shareholders to: a) submit a question; b) track its prioritization in the queue; and c) present the question virtually, either by phone or webcam.

- Instructions on how to access written responses to unanswered shareholder questions, which should made available within a reasonable time of the meeting’s conclusion.

Source: Report of the 2020 Multi-Stakeholder Working Group on Practices for Virtual Shareholder Meetings, Rutgers Law School Center for Corporate Law and Governance, Council of Institutional Investors, and Society for Corporate Governance, December 10, 2020.

In 2020, several climate-related resolutions voted at some large US companies gained majority support and passed. Companies that have not yet done so should consider the benefits of a process to gather information on their carbon footprint, design an emission-reduction strategy, and address the business risks resulting from global warming.

Climate change has solidified as one of the top ESG priorities for investors of US public companies. All large institutional shareholders have moved it to the front and center of their voting policies and stewardship guidelines. Typically, requests for disclosure on climate-related issues range from the company’s current carbon footprint to the mitigation targets it set to align with the standards of the Paris Agreement; and from the impact that rising temperatures can have on business operations to the risks resulting from maintaining the current levels of gas emissions. In some cases, companies are being asked to issue sustainability reports that comply with disclosure frameworks, such as the guidelines issued by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the Sustainability Accounting Standard Board (SASB)—which dedicate extensive sections to environmental performance metrics—or by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

In the Russell 3000, in the examined 2020 period, shareholders filed 75 proposals on climate-related issues and voted on 24 of them. Many of the filings were made at larger companies that are also included in the S&P 500 index (61 filed proposals in 2020, of which 19 were voted). They specifically target carbon-intensive sectors such as industrials (six voted proposals) and energy (five voted proposals), but with a few notable exceptions (for example, a proposal at Dollar Tree (Nasdaq: DLTR), a discount retailer) revealing that scrutiny of environmental practices is extending to all types of business. The most prolific proponent on this topic is shareholder advocacy non-profit As You Sow, which alone filed 24 resolutions. Other frequent sponsors include Mercy Investment Services, an investment fund affiliated to a religious group (seven proposals), and investment adviser Trillium Asset Management (four resolutions).

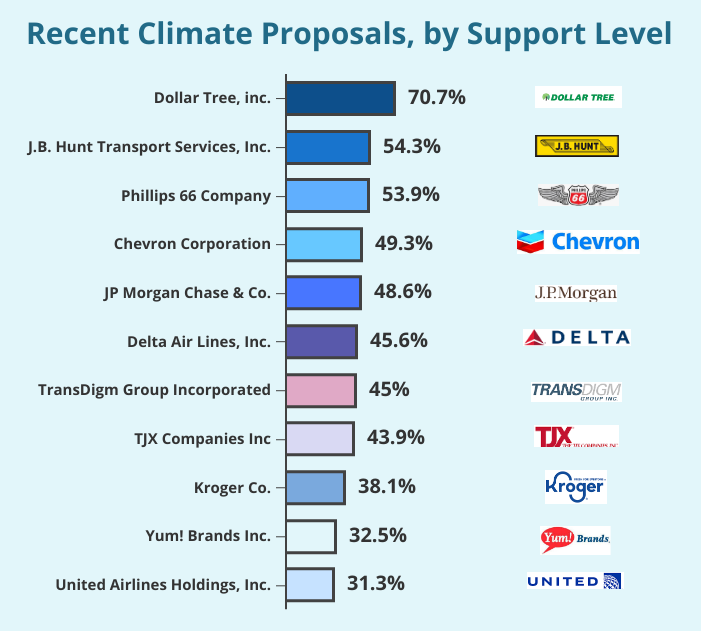

Thanks to the endorsement of larger institutions such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street, support levels for climate-related proposals has been increasing, from 24.1 percent in 2019 to 31.6 in 2020. Most importantly, while none of these types of proposals passed in 2019, four of those that went to a vote in 2020 received majority support: A proposal at J. B. Hunt Transport Services, Inc. (Nasdaq: JBHT) seeking a report on whether and how the company plans to reduce its contribution to climate change and align its operations with international goals (54.3 percent of for votes); a resolution demanding that Phillips 66 (NYSE: PSX) assess the business risks of expanding petrochemical operations and investments in areas increasingly prone to climate change-induce storms, flooding, and sea level rise (53.9 percent support); the request for Chevron (NYSE: CVX) to disclose details of its climate lobbying activities and explain how they align with its carbon-reduction strategy (which received 49.3 percent of for votes and 7.8 percent of abstentions, versus 42.9 percent of against votes); and the demand for greenhouse gas emission (GHG) targets at Dollar Tree, which made headlines for setting the record support level of any climate-related proposal ever put on a voting ballot (70.7 percent of votes cast).

At energy company Enphase Energy (Nasdaq: ENPH), shareholders approved a resolution that does not specifically refer to climate change but calls for the annual publication of a report on ESG performance and specifically cites waste, water reduction, and product-related environmental impact for the significant risks they pose to the business (51.8 percent support). Finally, later in the season, in mid-October 2020, a proposal calling for Procter & Gamble (NYSE: PG) to cull forest degradation and deforestation from the company’s supply chain passed with a remarkable 67 percent of votes cast in favor—an interesting development illustrating how the COVID-19 pandemic has shone a spotlight on the intersection of environmental and social practices (specifically, environmental and human health), whether speaking about the genesis of diseases or the disparate impact that they can have on disadvantaged populations.

In addition to majority-supported proposals, figures on withdrawals (there were 51 in the examined 2020 period alone) are an indication of the extent of the private corporate-investor engagement that is taking place on issues of environmental sustainability. For example, a resolution filed by As You Sow at Southern Company (NYSE: SO) was withdrawn after the company announced its commitment to net-zero carbon emission targets in line with the milestones of the Paris Agreement. There is also evidence that engagement preempts the filing of shareholder resolutions in the first place, and can be critical to the voting outcome of certain proposals: For example, a resolution on water resource risks that went to a vote in 2020 at poultry producer Sanderson Farms (Nasdaq: SAFM) was not supported by one of the company’s largest investors and failed to pass because the company had privately agreed to publish a SASB-aligned sustainability report.

What Is Driving Environmental Disclosure

In the last few months alone, many signals have been pointing to a building momentum behind climate change and environmental disclosure. They come from leading institutional investors and proxy advisors but also from the business community itself.

- In January 2020, BlackRock, the largest asset management company worldwide, joined Climate Action 100+, an initiative of more than 500 investors calling on companies to improve environmental governance, curb emissions, and become more transparent on climate-related risks and opportunities. The announcement followed a long list of other prominent signatories (including CalPERS, CalSTRS, Fidelity, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, and the pension funds of the City and State of New York) to what the United Nations has identified as one of the most consequential global initiatives to combat global warming.

- In March 2020, ISS announced the launch of a new specialty voting policy on climate-related factors. Under the new policy, the proxy advisor will recommend adverse votes on the re-election of board members in situations where the company appears (based on signals such as inadequate disclosure, norm violations, or the assessment of sector-specific materiality metrics) to have “failed to sufficiently oversee, manage or guard against material climate-change related risks.” In November 2020, Glass Lewis followed suit with a similar revision to its voting policies for S&P 500 companies, where the inadequate disclosure of environmental issues will first be noted as a concern in research reports and then, starting in 2022, trigger a recommendation to vote against the governance committee chair. In March 2020, BlackRock voted against the reelection of the chair of the audit committee of energy company National Fuel Gas (NYSE: NFG) because “[t]he company maintains very limited disclosure of climate risk and does not produce SASB or TCFD-aligned reporting…”

- C-suite attention to climate change and environmental sustainability is also increasing. In September 2020, just ahead of Climate Week, the Business Roundtable, a group of CEOs from some of the largest US corporations, issued a public statement supporting the commitment to slash US GHG emissions 80 percent below their 2005 levels (or what is required of the country, under the Paris Agreement, to help limit global temperature rise to 2 degree Celsius above pre-industrial measures). To achieve this target, the advocacy group reversed its earlier position on carbon pricing and endorsed legislation that would establish an economy-wide cap-and-trade system on the environmental impact of companies.

Insights for what’s ahead. In light of these developments, if they have not yet done so, companies can consider the following:

- Competence at the top. Companies should consider whether the board of directors and C-suites have sufficient expertise in relevant environmental matters. In a public statement issued in June 2020, Vanguard, the second largest shareholder in the world, outlined its new expectation that boards, in particular, become “purposefully composed of individuals who are competent on climate matters.” While this recommendation certainly applies to carbon-intensive businesses, for which environmental sustainability has a specific strategic significance, the contribution to the oversight role of the board coming from a recognized leader in the field can be a driver of innovation even in other sectors of the economy.

- Quality of internal controls. Companies should consider the periodic assessment of the quality of the internal control process used to oversee the business’ environmental impact, identify areas of vulnerability, and capture new opportunities. This task is critical as much as it can be incredibly arduous to perform, especially across large operations. In the last decade alone, many US companies have made tremendous progress in the development of sustainability programs, which often include environmental efficiency milestones. However, there is not yet a consistent body of empirical knowledge from which companies can draw common lessons, given the limited availability of reliable data across business sectors and the difficulty of reconciling the variety of commercial ESG rating services that have become available over the years. Furthermore, authoritative research has shown that at least 30 percent of an organization’s environmental impact is driven by firm-specific factors rather than industry membership—if so, each company would be carrying a level of “hidden liabilities” that, if adequately measured and priced by the market, could potentially erode some of its value. For this reason, and until the field is better codified, companies cannot underestimate the importance of internal control process improvements. On this front, in the next couple of years it will be interesting to monitor the legislative developments in the European Union, which is considering requiring boards of directors and senior management teams to carry out—as part of their legal duty of care—“due diligence” to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for actual or potential environmental impacts in their own operations and supply chains.

- Environmental disclosure enhancements, with a specific attention to the intersection between environmental and social impact. Finally, companies should consider how to enhance the disclosure of environmental issues in sustainability reports and SEC filings. To be sure, one of the main difficulties is to make sense of the competing sets of standards that have been multiplying over the years, which helps to explain the attempts to promote a reconciliation and consolidation process in the field led by organizations such as the World Economic Forum and The Conference Board. Prompted by these initiatives, in the fall of 2020, five major standard-setting institutions (the Carbon Disclosure Project, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board, and the International Integrated Reporting Council, in addition to GRI and SASB) issued a joint statement of the intent to work together toward a single framework of widespread adoption. Ultimately, in the next couple of years, this consolidation process may be further accelerated by the Climate Plan of the new Biden Administration, which includes directing the SEC by executive order to require “public companies to disclose climate risks and the greenhouse gas emissions in their operations and supply chains.”

Amid an unprecedented health crisis and public protests over racial and social injustice, the focus on human capital management (HCM) practices has reached a tipping point. Companies are called to strengthen internal policies and expand disclosure on the subject.

HCM resolutions have dramatically grown in prominence in the 2020 proxy season, as the COVID-19 health crisis and the social unrest following the death of George Floyd called the attention of business leaders to issues of workforce welfare and equality. With the adoption of new SEC rules on the disclosure of material human capital metrics and the public stance assumed by many prominent institutional shareholders, HCM matters are expected to continue to take center stage in the coming AGM seasons.

Across the Russell 3000, in the examined 2020 period, shareholders filed 63 proposals on HCM issues and voted on 34 of them. Investor requests in this area ranged from board to workforce diversity (12 and 16 filed proposals, respectively, of which four and 11 went to a vote) and from the disclosure of gender pay equity (12 proposals, all voted) to the adoption of employee arbitration policies (nine proposals, of which two were voted). As observed for proposals on climate change disclosure, the majority of these submissions are made at larger companies that also belong to the S&P 500 index; however, we have recorded proposals on board and workforce diversity targeting smaller businesses, with annual revenue under $1 billion. While environmental resolutions primarily target carbon-intensive industries, the sector analysis shows a wider distribution of HCM proposals across business types and a specific focus on sectors, such as retail and industrials, that were hit hard by the pandemic and reported massive layoffs or furloughs. Hedge fund Arjuna Capital, shareholder advocacy non-profit As You Sow, and the public retirement funds managed by the Office of the New York City Comptroller are the main proponents of these types of requests. To be sure, shareholder resolutions are just one of the tactics used under the Boardroom Accountability Project 3.0 by the NYC Comptroller’s Office, which, since October 2019, has also sent tens of letters to large US public companies that had not yet disclosed a diversity search policy requesting the consideration of women and other racially/ethnically diverse candidates for board directors as well as chief executive officer positions. Many of the companies targeted by this new iteration of the Boardroom Accountability Project adopted and publicly disclosed CEO/board diversity search policies before the proposals were even included in their proxy statements.

Average support levels for HCM-related shareholder proposals remain well below the 50-percent mark, even though votes recorded in the last few years show an upward trajectory for some of the sub-types. In particular, the highest support averages are seen among proposals on diversity (38.2 percent for those on workforce diversity, up from 28.6 percent in 2017; and 36.8 percent for the diversity of boards of directors, significantly up from the 18.3 percent tallied in 2018). Overall, seven of the shareholder resolutions voted on the HCM-related categories tracked by The Conference Board and ESGAUGE received majority support and passed during the 2020 proxy season, compared to only four in the same period in 2018 and three in 2017:

- At air freight and logistics company Expeditors International (Nasdaq: EXPD), a member of the S&P 500 index, 52.7 percent of votes cast by shareholders approved a proposal requesting that the initial list of candidates used by the company to select director nominees and CEO successors include qualified female and racially/ethnically diverse individuals. At Tennessee-based National Healthcare Corporation (AMEX: NHC), a proposal on the publication of a report detailing the concrete steps the company is taking to enhance board diversity passed with 57.9 percent of votes and only 2.2 percent of abstentions.

- The demand for transparency on metrics pertaining to workforce diversity and inclusion was approved at four companies: Two in the consumer discretionary sector (Genuine Parts Company (NYSE: GPC), with as much as 74.4 percent of votes cast; and O’Reilly Automotive (Nasdaq: ORLY), with 64.9 percent support level); one at industrial and capital good supplier Fastenal Company (Nasdaq: FAST), with 57.7 percent support level; and one at cybersecurity technology developer Fortinet (Nasdaq: FTNT), with 69 percent support level. The proposals at GPC and ORLY, in particular, requested that the company’s reporting comply with the disclosure standards that SASB sets on the matter.

- Shareholders of Chipotle Mexican Grill, Inc. (NYSE: CMG) supported a proposal regarding the preparation of a report on the use of contractual provisions requiring employees to arbitrate employment-related claims—including the proportion of the workforce subject to such provisions; the number of recent employment-related arbitration claims initiated and decided in favor of employees; and any changes in policy or practice the company has made, or intends to make, as a result of California’s ban on agreeing to arbitration as a condition of employment. The proposal passed with 50.5 percent of votes cast in favor.

Instead, all of the 12 voted resolutions to demand transparency on employee pay gaps across gender and other minorities failed, just like in earlier years, with an average 2020 support level of only 12.6 percent of votes cast. Similarly, proposals to strengthen corporate policies to prevent sexual harassment received a 19.1 percent average support level (up from 12.4 percent in 2018) and none of the four voted in 2020 passed. Amazon (Nasdaq: AMZN) was the recipient of a proposal requesting information on how the company is overseeing employee health and safety in its facilities in light of heightened risk posed the COVID-19 pandemic; but the resolution, filed by an investment fund affiliated to the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, was omitted from the voting ballot after the company was granted no-action relief from the SEC.

Insights for what’s ahead. In its August 26, 2020 amendments regarding the modernization of Regulation S-K, the SEC requires U.S. public companies to disclose “a description of the registrant’s human capital resources, including the number of persons employed by the registrant, and any human capital measures or objectives that the registrant focuses on in managing the business (such as, depending on the nature of the registrant’s business and workforce, measures or objectives that address the development, attraction and retention of personnel).” Rather than prescriptive, the rule is principle-based and relies on the notion of materiality, which varies from business to business; its practical effect on corporate disclosure will only be measured over time.

Since the passage of the new SEC rules, advisory firms and business associations have started to formulate guidance on how companies should approach their disclosure of material HCM practices. For example, the World Economic Forum, in collaboration with Willis Towers Watson, has released a human capital accounting framework to enable boards of directors and management to track how their investment in people translates into better business outcomes. The Conference Board also recently convened a working group on HCM oversight, engaging with more than 100 executives from publicly held and private corporations as well as representatives from institutional investors and professional service firms. In December 2020, the group released recommendations that will prove quite valuable to corporations in the coming proxy voting seasons. The following insights draw on those and other resources:

- Companies should clarify and strengthen the role of the board of directors and its committees in the oversight of HCM. This exercise includes reviewing committee charters and governance principles to ensure they clearly assign responsibilities. It also extends to assessing HCM performance and examining, with a critical eye, the company’s workforce policies so as to eradicate bias that may affect the process for the selection, promotion, and compensation of employees and their managers. In recent years, boards have sought to add directors with specific areas of expertise that are relevant to their business, such as technology and finance. As HCM oversight is increasingly elevated to the board level, directors should consider including HCM skills to their matrices and, as part of their periodic self-assessment, evaluate if they should obtain additional expertise in the field—whether directly by recruiting a new board member or through board education or the engagement of outside experts.

- With a large majority of their costs estimated to be tied up in people, companies should maintain data on human capital and its performance to ensure it matches the business’ strategic needs. Key HCM metrics—from diversity and inclusion to learning and innovation, and from employee litigation and arbitration to health and safety—should be collected and verified through internal processes and controls, and then regularly reported to the board so that it remains apprised of strengths and can focus on how to address gaps and vulnerabilities. A set of HCM metrics is ideally composed of quantitative and qualitative indicators—quantitative to allow for setting, tracking, and holding management accountable for achieving goals, and qualitative to ensure the link with business strategy and provide the proper context. This evaluation should also encompass corporate culture as a whole, which the board of directors should understand through more direct interactions with the workforce and beyond what’s contained in employee engagement survey results.

- What stakeholders want to know is whether a business has the right workforce to meet current and emerging strategic needs, and whether the company is mitigating HC-related risks (including bias, discrimination, health-related risks, and an otherwise unsuitable work environment) that could undermine its value. As they prepare for more thorough HCM reporting, companies should monitor the undergoing process for the harmonization and consolidation of existing ESG disclosure frameworks. The SEC views information as material if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important in making an investment or voting decision. Until a single, widely accepted framework emerges, companies should inform this notion of materiality of HCM metrics by assessing the relevance of such metrics to the pursuit of the business strategy. For this purpose, they can draw from any of the currently available reporting standards that suit the objective of effectively communicating to the public on those metrics. In recent years, large institutional investors have gained deep knowledge of existing reporting standards: Therefore, engagement with those investors on HCM matters offer an opportunity to discuss the rationale for the choice of a certain disclosure standard and receive helpful feedback.

- As mentioned, the new SEC rules do not include a definition of “human capital” or a list of metrics to disclose. As a result, as they start to develop, HCM disclosures under the rules will be tailored to individual businesses and influenced by what peer companies also report. We expect peer benchmarking in this area to grow, which is why in 2021 The Conference Board, in collaboration with ESGAUGE and other prominent knowledge partners, plans to extend its ESG Advantage Benchmarking Platform to the HCM field. HCM is a complex topic and it is realistic to expect that its disclosure will evolve and improve over time. Learning from peers will be part of this improvement process and can contribute, incrementally, to the development of the field. Peer benchmarking enables organizations to track material disclosures within industries and company size groups, using comparative analysis to inform their own reporting process. Companies should consider reviewing peer disclosures on HCM practices and remain apprised of available resources to streamline and automate the analysis.

The Call for Board Diversity

The issue of diversity of board members deserves a few additional notes. The scrutiny of gender and racial/ethical diversity practices will continue to intensify, driven by multiple factors.

More and more institutional investors are following the lead of prominent asset managers such as State Street, Vanguard, and BlackRock, moving diversity to the front and center of their corporate stewardship initiatives. We also mentioned the Boardroom Accountability Project already, and how consequential it has been in the few months since its official launch.

In February 2020, proxy advisor ISS started to implement a new adverse voting recommendation against the chair of the nominating committee of companies with no female board members; only a few months later, the firm announced its plan to extend in 2022 the voting policy to situations where the board has no apparent racially or ethnically diverse board member.

While legislative initiatives have stalled in the U.S. Congress in the last few years and may be rekindled under the auspices of the new Biden Administration, in September 2020, the State of California has doubled down on its requirement of a female quota for public company boardrooms by amending its Corporations Code so that one and three directors (depending on the size of the board) would be selected from an underrepresented community by the end of 2022. On gender diversity, the States of New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Washington have followed the California model and introduced their own legislative proposals setting a female quota for public company boardrooms.

Finally, in December 2020, Nasdaq filed a proposal with the SEC to adopt new listing rules that would expect most of its listed company to disclose consistent statistics on the diversity of their board of directors and to have (or explain why they do not have) at least two diverse directors—one who self-identifies as female and one who self-identifies as either an underrepresented minority or LGBTQ+.

For all of these reasons, boards should make gender and racial/ethnical diversity an integral part of the ongoing board (and CEO) succession planning process. While this is particularly important for those smaller companies where diversity is still lacking, even companies with some diversity in their top leadership should avoid the risk of being complacent on this important topic and of adopting a check-the-box, compliance approach. Where more stringent prescriptions (such as the one set for California-based companies) do not apply, the efforts to improve diversity may include: requiring a diverse slate of candidates for each open position; ensuring that nominating committees, which take the lead in the director recruitment process, are diverse; and considering diversity when making board and committee leadership appointments to help leverage their networks.

Other trends to watch in 2021

Director elections. Average support levels in director re-elections has gradually declined in recent years: in the Russell 3000, for example, it went from 98.2 percent of votes cast in 2017 to 94.8 percent in 2020. Only seven directors in the entire index failed to receive majority support in 2017, while the number climbed to 53 in 2020 alone. Similarly, the number of directors who received less than 70 percent of votes cast was only 83 in 2017 and rose to 319 in 2020. While these numbers are hardly noticeable if one looks at the big picture (almost 16,000 directors were up for re-election in the Russell 3000 in 2020), they are part of a trend that was not observed before. In particular, it can be attributed to the position publicly assumed by many large investment institutions and by proxy advisors to intensify their scrutiny of board composition and refreshment and to increase board accountability on key ESG issues. Companies should no longer take investor confidence in their nominees for granted and must persuasively articulate the reasons for their board composition choices.

Political contributions and lobbying activities. Over the last few years, investors have increasingly been focusing on political contributions and lobbying expenditures of corporations, demanding more transparency on these issues. Five resolutions that went to a vote in 2020 passed, while a dozen more barely missed the majority support threshold. In the 2020 proxy season, in particular, there has been renewed scrutiny of the alignment between companies’ public statements (in particular in sensitive ESG areas such as diversity, racial justice, and environmental protection) and the political and lobbying activities of its industry associations. Companies that have not yet done so should consider adopting a statement of purpose and ensuring that their strategy, governance, and risk management (including their contributions to support political candidates or to pursue public policies advancements) are informed by and consistent with such purpose.

CEO/board chair separation. This is the governance-related topic to watch in the next proxy season. In 2020, unprecedented votes led to the approval of proposals on the appointment of an independent board chair at Baxter International (NYSE: BAX) and Boeing Company (NYSE: BA), with many other similar resolutions receiving the support of more than 40 percent of votes cast and average support level rising to 34.4 percent (it was 29.1 the year before). As the demand for the separation of CEO and board chair positions continues to grow, companies should review their board and committee leadership and ensure investors are persuaded about the independence of critical governance and oversight functions.

Say-on-pay votes and other compensation issues. While average support for say-on-pay management proposals in the Russell 3000 index remained strong in the 2020 season at 90.1 percent, 47 companies failed to received majority support and 115 companies failed to reach at least 70 percent support—the threshold below which proxy advisor ISS begins to scrutinize companies’ responsiveness to shareholder concerns. Of course, these votes refer to pre-COVID-19 compensation decision. It remains to be seen how investors and proxy advisory firms will evaluate the compensation changes made in response to the global pandemic. The Conference Board and ESGAUGE have been tracking such changes in a public, live database.

SEC no-action letters. Companies continue to seek permission from the SEC to exclude from the voting ballot shareholder proposals relating to ESG matters. The trend was confirmed from an analysis of 2020 SEC no-action letters and is expected to continue in the coming years, especially as the volume of proposals in the environmental and social sphere rises. Out of the 237 requests for no-action relief submitted by Russell 3000 companies in the examined period of the 2020 voting season, 27 were related to environmental issues (15 of them were granted by the SEC) and 46 to human right and social (including human capital) issues (16 granted). The most common bases for requesting exclusion were that the proposal related to the ordinary business of the company (and would therefore translate into an attempt at micromanaging the company) or that it had been substantially implemented already.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print