Marco Pizzitola is a consultant, and Joe Sorrentino and Stephan Bosshard are principals at FW Cook. This post is based on their FW Cook memorandum.

Effective CEO succession, the planning and execution of which can span several years, is critical to the potential success of a company. For a CEO to set and execute a winning strategy, a stable, engaged, and high-functioning team is needed in the C-suite. However, CEO succession can often result in the departure of other senior executives—some of whom may have been candidates for the CEO role themselves, and some of whom may be less aligned with the strategy of the new leadership. Such departures are often those who are most respected in the market—and thus, essential to ensure investor and company confidence throughout the transition.

One common strategy to limit post-succession turnover is to make special retention grants to some or all of the leadership team. Retention grants include cash or equity awards, with delayed vesting, made in addition to regular, annual compensation. FW Cook investigated the effectiveness of this strategy and discovered that special retention grants have a strong effect in the immediate term, but that the impact wanes quickly.

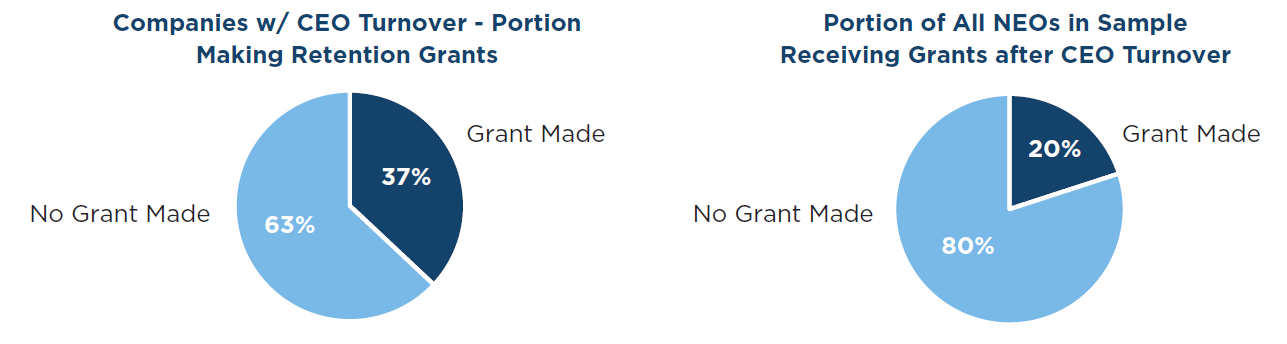

To study the effectiveness of retention grants, FW Cook researched large-cap organizations in the US, identifying a sample with CEO turnover from 2010 to 2016 (65 in total)—and among those, companies making accompanying retention grants to named executive officers (NEOs). Nearly 40% of the sample companies made succession-related retention grants to non-CEO NEOs.

In short—the ability of post-succession retention grants to add “glue to the seat” is strongest in the first two years after CEO turnover. Executives who receive these grants are significantly more likely to stay with the organization for the first two years following a CEO transition than those who do not receive them.

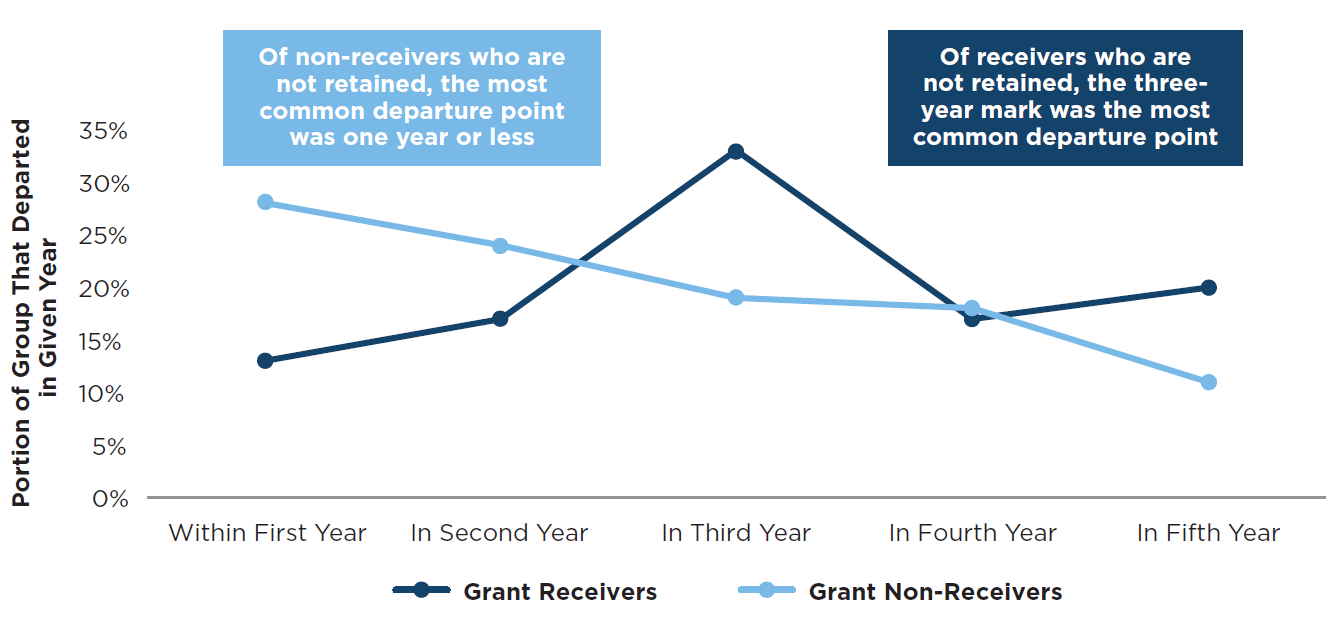

Among the NEOs in the sample receiving retention grants, only 8% departed within the first year. Among those not receiving retention grants, the departure rate in the first year was almost double (15%). In the second year, this difference is less pronounced—10% and 13%, respectively. Another way to view the effectiveness of retention grants is to look at only NEOs who eventually departed, and whether a retention grant had an impact on how long the executive remained with the organization. The following chart shows, among NEOs who departed within the first five years after CEO succession, the proportion that did so in each year.

Methodology

Succession events and related retention grants were captured as disclosed in public company filings. Due to the need for “lag time” to determine if the retention grants were effective, FW Cook studied CEO turnover occurring from 2010 to 2016 and analyzed retention of Named Executive Officers in the following five years. Turnover included both internal and external CEO appointments. Among companies that made retention grants in this context, the disclosure was further studied to determine the nature of the grants, as well as the career path of the executives receiving the grants. Involuntary terminations, where discernable, were not included in the study.

Among grant receivers, the most common departure point was in the third year after the succession (33% of those who left within the first five years, and 29% of all who eventually departed) suggesting that NEOs will often leave a company after receiving the entirety of an award with a three-year vest or majority of an award with a five-year pro-rated vest. This is shown in the departure curves above, with spikes at the three- and five-year points (in line with common vesting schedules).

In contrast, among grant non-receivers, the most common departure point was within one year of CEO succession (28% of those who left within the first five years, and 16% of all who eventually departed). Our research found that departure rates for non-receivers show a steady downward trend through five years, suggesting that stability of the leadership team is most tenuous in the initial year of a transition, and special one-time awards may provide an effective retention tool during that time.

This highlights an important fact: while retention grants often work as intended in the short term, they are not a permanent solution. Capitalizing on the added time that executives remain is critical to developing or recruiting future leaders and to promoting organizational stability for a period of time following succession.

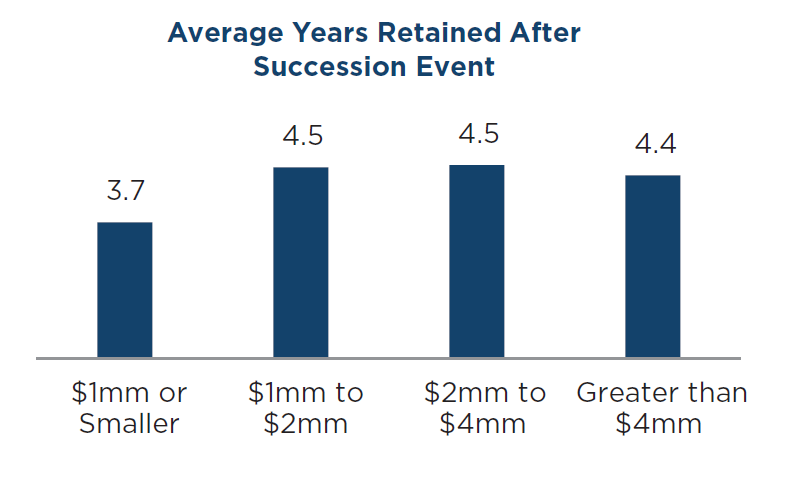

Further, the effectiveness of these grants in retaining executives shows a diminishing marginal return. The more valuable the grant, the stronger its ability to retain—but the ability to do so levels off once the grants pass the $2 million mark as shown below:

How Do These Grants Affect The “Point of Departure?”

The portion of grant receivers who were retained through 80% or more of the vesting term (e.g., those who remained at the company for four years after receiving a grant that vested in annual installments over five years) was 71%. This suggests that retention grants are not entirely effective in retaining executives for their intended length of time, as defined by the vesting period. Rather, the true effectiveness of these grants is in ensuring retention in the shorter term (e.g., less than three years).

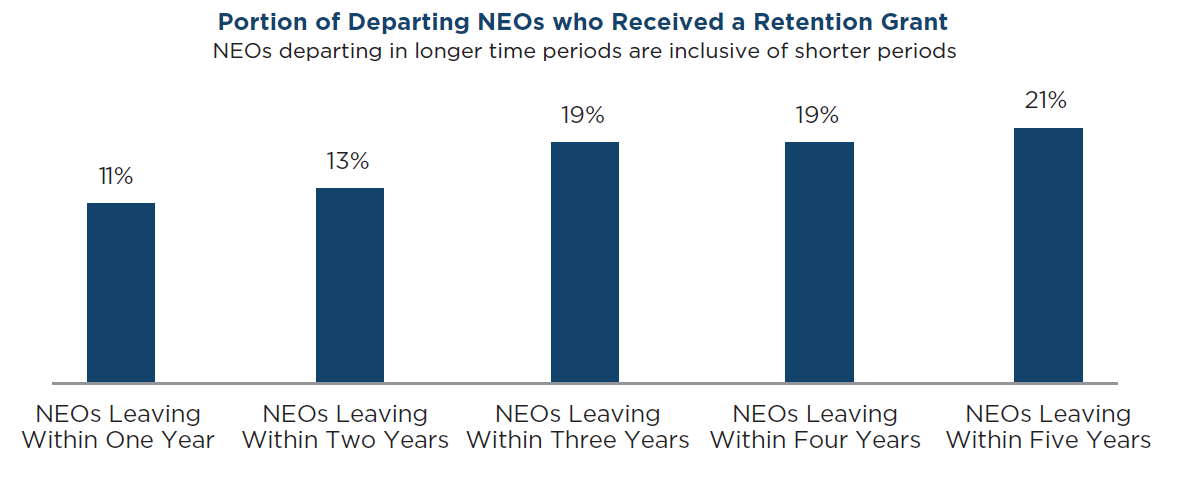

Our analysis suggests that retention grants have a significant impact in certain scenarios:

- Of those who left within two years, only 13% had received retention grants

- When expanding to include those who left within five years, 21% had received grants

In other words, companies can minimize the likelihood of early departures (within one or two years of the succession event) by granting retention awards. This can be an effective tool in ensuring continuity through a critical transition period.

How Are These Grants Typically Structured?

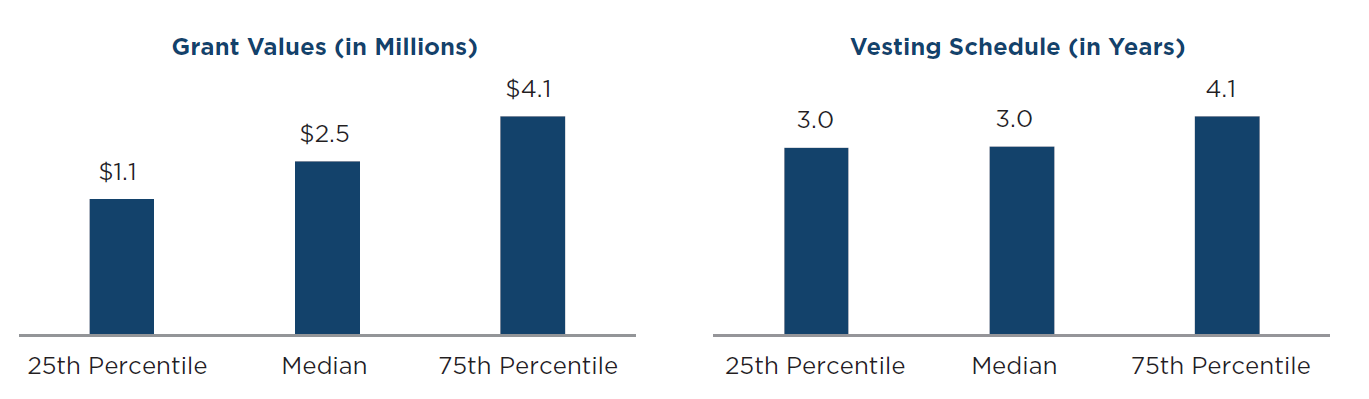

The average (mean) size of a retention grant was $3.3 million and, on average, grants vest over 3.6 years. The 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentiles of awards had grant date fair values of $1.1 million, $2.5 million, and $4.1 million, respectively.

Consistent with standard practices for regular long-term incentive awards, three years was the most common vesting period for retention grants in our sample. Ratable (installment) vesting schedules were used in 78% of grants. The average total vesting period of a ratable grant was 3.9 years, while the average total vesting period of a cliff-vesting grant was 2.5 years.

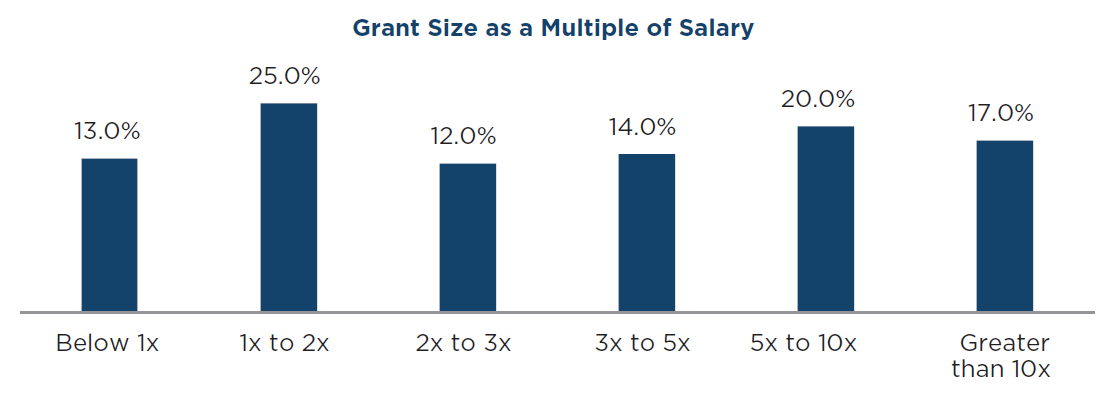

As a multiple of salary, one- to two-times annual salary was the most common retention grant size. Approximately half were three-times salary or less, while over a third were five-times salary or greater. However, we found little correlation between grant size relative to salary and years retained, implying the retentive power of these grants is more than simply monetary (e.g., the statement of worth communicated by simply making the grant at all may have some retention hook).

How Common Is This Retention Strategy?

Special retention grants are relatively common practice among large, publicly traded companies undergoing CEO succession. In our sample, 37% of those with succession events made related retention grants to at least one of the NEOs. In aggregate, retention awards were allocated to 20% of NEOs, as companies typically provided retention grants to only NEOs considered as potential future CEO successors, or to those viewed as critical to functional or business unit excellence.

Further Considerations

Succession is not a “one and done” event. Effective succession planning is an ongoing process that should be monitored and reassessed on a regular basis. The years (or even mere months) following CEO succession are not just a time to retain quality leadership in the C-suite, but also a time to develop those leaders further. Beyond their importance for stability across the organization, some executives may be considered CEO candidates in the future or may need to step into the role on an interim basis in the event of an unexpected departure or leave of absence.

Furthermore, leadership departures have implications throughout the organization. Retention of top executives across functions or divisions allows those business units to further develop their own leaders and to maintain continuity during a time when the whole organization may be experiencing a change in strategy. The immediate years following changes in leadership are crucial to ensuring a strong talent development program in the more junior and high-potential ranks as well as addressing concerns at the top of the organizational chart.

Without question, retention grants are just one potential component of an effective succession planning and retention strategy. Other important factors that influence whether an executive decides to stay with an organization include experience in the current role, proximity to retirement, personal ambition, external perceptions of the executive’s qualifications for a CEO role, emotional connection to the company, among others. The data analyzed here seek not to measure retention grants as a perfect determinant of retention, but as a quantification of a major contributing factor.

As many companies award equity annually over an executive’s career, much of which is subject to delayed vesting schedules, it is also valuable to examine the “holding power” of an executive’s unvested equity on a recurring basis and assess whether a special equity award, unrelated to turnover, may be necessary. A further exploration of correlation between outstanding equity value and retention results would build upon the findings here.

Print

Print