Andrew G. Gordon is partner at Equilar, Inc.; David F. Larcker is the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business; and Courtney Yu is Director of Research at Equilar, Inc. This post is based on a recent paper by Mr. Gordon; Mr. Larcker; Ms. Yu; John D. Kepler, Assistant Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business; Amit Batish, Manager of Content and Communications at Equilar; and Brian Tayan, researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here) and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

We recently published a paper on SSRN, Human Capital Disclosure: What Do Companies Say About Their ‘Most Important Asset? that examines corporate human capital disclosure choices following the SEC’s revision of Regulation S-K items last year.

Over 20 years ago, McKinsey penned a famous piece called the “War for Talent,” which argued that corporate success in the dawning information age would hinge on a company’s ability to attract, retain, and develop the most talented members of the labor force. The concept that high-performing talent is both scarce and critical to performance triggered a cottage industry of professionals and specialists dedicated to developing “strategic” human resource programs that position companies to “win the war for talent” and serve as a competitive advantage. Those efforts are broadly referred to as human capital management (HCM).

The primary challenge, which still holds true today, is how to measure the contribution of human capital to corporate strategy and performance. Human capital is an intangible asset (employees are not capitalized on the balance sheet), and its value only shows up indirectly in future corporate results. While some studies link HCM to future performance, the methods for measuring HCM are tenuous at best. For example, Edmans (2011) finds that employee satisfaction scores (a proxy for HCM quality) are positively correlated with long-term stock performance. Employee satisfaction, however, is not a comprehensive measure of HCM.

For more than two decades, researchers and practitioners have worked to develop metrics to shed light on the contribution of human capital to results. These metrics cover all aspects of HCM programs, including skill requirements and gap analysis, sourcing strategies, recruitment pipelines and yields, talent development, promotion, retention, satisfaction, diversity, productivity, safety, and compensation and incentives. While these metrics in and of themselves do not produce a bottom-line figure that captures human capital value, they are generally useful indicators for assessing HCM quality and inform managerial decision making.

Some companies make use of HCM metrics to improve internal processes. For example, Google is purportedly a company that uses advanced analytics to improve corporate performance through HCM. Google employs a team of trained researchers to mine workforce data to find ways to boost productivity and increase retention. The results of this analysis are used to optimize organizational and reporting structures, improve application and recruitment processes, and identify promising leadership behaviors for incorporation into performance and incentive systems.

The results of HCM analysis are rarely shared publicly. HCM metrics are considered highly proprietary information, the disclosure of which can diminish a company’s competitive advantage. However, even when not proprietary, large corporations appear to be reluctant to disclose human resources data. For example, all companies are required to report Equal Employment Opportunity data with racial and gender diversity data by job function to the Department of Labor, but few companies make this report public even though the competitive implications of this data are fairly benign.

With sustainability and stakeholder capitalism high on today’s corporate agenda, pressure has grown for companies to demonstrate their commitment to stakeholders, including their employee base. Under the moniker of ESG, investors are demanding increased visibility into human capital management. The most vocal calls have been for the publication of diversity data. However, some investor groups advocate more comprehensive ESG disclosure.

Nonprofit organizations, such as the Sustainability Standards Accounting Board and the Global Reporting Initiative, have tried to offer solutions by proposing stakeholder-related reporting metrics, including employee-related metrics. These standards are not endorsed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, and few companies disclose this information through Form 10-K.

In acknowledgement of the value of HCM information to investors, the SEC updated human capital disclosure requirements in November 2020 as part of a broad overhaul of Form 10-K business disclosure. Historically, companies had only been required to disclose their total number of employees. Some disclosed division or geography, full-time versus part-time employees, or the number represented by labor unions, but any disclosure beyond this was rare.

Under the revised rules, companies are required to

provide a description of the registrant’s human capital resources, including in such description any human capital measures or objectives that management focuses on in managing the business, to the extent such disclosures would be material to an understanding of the registrant’s business taken as a whole.

Consistent with the principles-based approach the agency favors, no specific metrics are required.

In this Closer Look, we examine early disclosure choices that companies have made under new guidance to evaluate the information they share about their employment practices. We assess the quality of disclosure and the insights it provides into HCM system, using data provided by Equilar.

We find that while some companies are transparent in explaining the philosophy, design, and focus of their HCM, most disclosure is boilerplate. Companies infrequently provide quantitative metrics. One major focus of early HCM disclosure is to describe diversity efforts. Another is to highlight safety records. Few provide data to shed light on the strategic aspects of HCM: talent recruitment, development, retention, and incentive systems. As such, new HCM disclosure appears to contribute to the length but not the informativeness of 10-K disclosures.

Early HCM Disclosure

Our sample includes the first 100 Form 10-K filed by companies with at least $1 billion in market capitalization following the SEC rule revisions of November 2020, using data provided by Equilar. We chose the first 100 companies in order to see what information companies would voluntarily disclose under the broad guidelines of the rule without the benefit of reviewing the disclosure of their peer group.

Disclosure Length

The new rules clearly led to an increase in disclosure length. The typical HCM filing has a median word length of 782, a 9-fold increase over the previous year’s disclosure (84 words). Current disclosure is approximately the length of an op-ed piece in a national newspaper.

While most companies increased disclosure length materially, not all did. 20 percent of our sample left disclosure largely the same.

Disclosure Areas

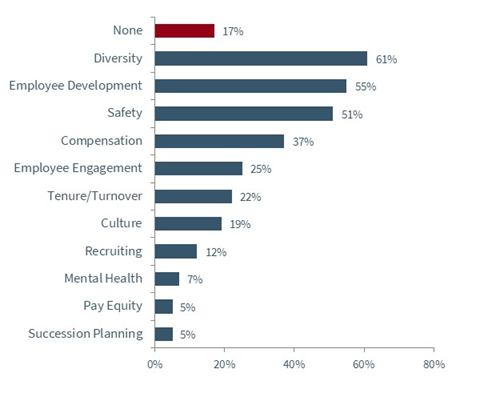

Diversity and inclusion are the areas of HCM most frequently added this year (61 percent of companies). This was followed by employee development efforts (55 percent), safety (51 percent), and compensation practices (37 percent). Other areas voluntarily disclosed are employee engagement efforts (25 percent), employee turnover or tenure information (22 percent), culture (19 percent), recruiting practices (12 percent), mental health (7 percent), pay equity (5 percent), and succession planning (5 percent). See Exhibit 1.

Selections from our sample exemplify the exceedingly generic nature of the language used.

Diversity and Inclusion. We are committed to our continued efforts to increase diversity and foster an inclusive work environment that supports the global workforce and the communities we serve. We recruit the best people for the job regardless of gender, ethnicity or other protected traits and it is our policy to fully comply with all laws (domestic and foreign) applicable to discrimination in the workplace. Our diversity, equity and inclusion principles are also reflected in our employee training and policies. We continue to enhance our diversity, equity and inclusion policies which are guided by our executive leadership team. [Heico]

Employee Development. The Company provides its employees with tools and development resources to enhance their skills and careers at the Company, including: (i) encouraging employees to discuss their professional development and identify interests or possible cross-training areas during annual performance reviews with their supervisors; (ii) offering corporate and technical training programs based on position, regulatory environment, and employee needs; (iii) providing a tuition aid program for educational pursuits related to present work or possible future positions; (iv) providing talent review and succession planning; (v) providing opportunities for on-the-job growth, through stretch assignments or temporary projects outside of an employee’s typical responsibilities; and (vi) offering one-on-one meetings for supervisory employees at the Company’s regulated subsidiaries to discuss career pathing and employee development. [National Fuel Gas]

Compensation and Benefits: We provide robust compensation and benefits. In addition to salaries, these programs, which vary by country/region, can include annual bonuses, stock-based compensation awards, a 401(k) plan with employee matching opportunities, healthcare and insurance benefits, health savings and flexible spending accounts, paid time off, family leave, family care resources, flexible work schedules, adoption and surrogacy assistance, employee assistance programs, tuition assistance and on-site services, such as health centers and fitness centers, among many others. [Toro]

Disclosure Metrics

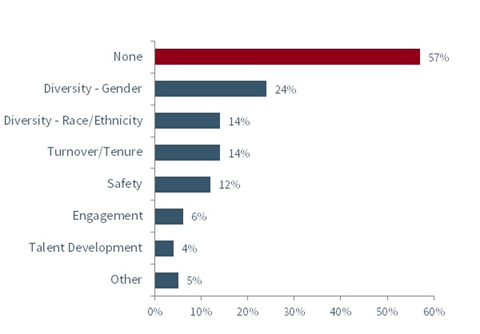

Next, we looked at the extent to which companies use quantitative metrics to describe their HCM efforts. Only 43 percent of companies in our sample reported one or more quantitative metrics (beyond the historically reported metrics of employee count and union representation), while 57 percent provided no quantitative metrics. Gender diversity was the most frequently reported metric (24 percent of companies), followed by racial diversity (14 percent), average employee tenure or voluntary turnover rates (14 percent), safety or incidents rates (12 percent), engagement metrics (6 percent), talent development (4 percent), and other (5 percent). See Exhibit 2.

These numbers demonstrate the paucity of quantitative metrics and underscore the generic nature of early HCM disclosure. Without concrete figures, it is difficult to believe that investors will be able to monitor a company’s HCM performance, make reasonable assessments about its performance relative to peers, or understand the dollar investment that a company makes to support the development of its employee base.

Still, some companies provide quantitative HCM metrics, and these metrics demonstrate the potential value of concrete disclosure to shareholders, provided the metrics are relevant to the company and industry. Examples include the following:

Diversity: As of October 3, 2020, our domestic workforce was approximately 40% gender diverse, and of our domestic team members, our workforce was approximately 33% white, approximately 27% Hispanic or Latino, approximately 25% Black or African American, and approximately 11% Asian American. [Tyson Foods]

Safety: Targets for a reduction in recordable Incident Frequency Rates (“IFR”) and Lost Time Case Rates (“LTCR”) are set annually. For 2020, we collectively met our targets. We achieved an overall IFR of 0.92, meaning that for every 100 employees, 0.92 employees incurred an injury that resulted in recordable medical treatment. The LTCR was 0.26, meaning that for every 100 employees, 0.26 individuals experienced an incident that resulted in days away from work. [Navistar International]

Turnover and Retention: Our focus on retention is evident in the length of service of our executive, regional and divisional management teams. The average tenure of our executive team and homebuilding region presidents is 27 years and the average tenure of our homebuilding division presidents and city managers is greater than 10 years. [D.R. Horton]

Employee Engagement: We regularly collect feedback to better understand and improve the employee experience and identify opportunities to continually strengthen our culture. In 2020, 96% of employees participated in our annual employee survey. Last year we achieved highest level of employee engagement (top quartile). Employees’ highest rated areas were the following: diversity and inclusion (95%) and ethics and integrity (95%). [HP]

Other Indicators of HCM Quality

Next, we reviewed other aspects of corporate disclosure for evidence of the degree to which companies prioritize HCM.

Named Executive Officers

First, we examined whether a senior human resources official is included as a named executive officer (NEO), the three most highly compensated executive officers along with the CEO and CFO. A company that compensates a human resources executive as an NEO likely also invests in HCM and talent development as strategic initiatives. We find that only 10 percent of our sample list the chief human resources as an NEO; 90 percent do not.

CEO Compensation

We also examine the CEO compensation program, as described in the most recent Form DEF-14A, to see whether HCM metrics are included in short- and long-term, performance-based incentive awards. It is difficult to argue that HCM is a corporate priority if the CEO is not explicitly rewarded for the achievement of HCM goals.

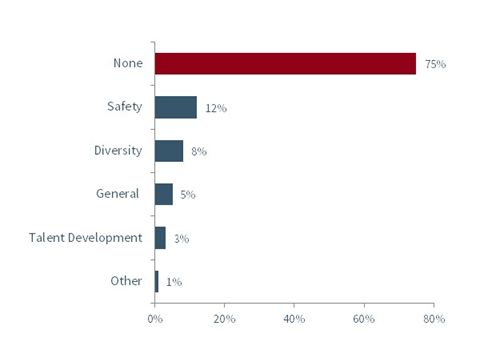

25 percent of companies in our sample include one or more HCM metric in the CEO’s annual incentive plan; 75 percent do not. Of these, only 11 provide a percentage weight to the metric. The remaining 14 do not but instead use the HCM metric as a general factor in evaluating the achievement of goals.

Safety measures are the most frequently used HCM metrics in CEO compensation plans (12 percent of companies). Other HCM metrics are diversity and inclusion (8 percent), general leadership and cultural goals (5 percent), talent development or employee engagement (3 percent), and employee well-being (1 percent). See Exhibit 3.

We found no company in our sample that includes HCM as a milestone or metric in rewarding long-term incentive programs (LTIPs).

Conclusions

The SEC revised human capital management disclosure rules in response to market demand for increased transparency into human capital practices so that investors and stakeholders would gain greater insight into how companies prioritize, manage, and measure the performance of their employee base. Early disclosure suggests that this objective is unlikely to have been met. While newly issued reports are substantially longer than historical disclosure, they are characterized by a general lack of informativeness. The emphasis appears to favor qualitative language over quantitative metrics, whereas informativeness would improve if the reverse were true. It might be the case that, over time, market pressures coalesce around more uniform and higher-quality reporting standards—as corporate disclosure is held up against peer groups. However, without concrete improvement, it does not appear that current HCM disclosure is relevant for assessing corporate performance or understanding how employee development programs contribute to strategy, value creation, or competitive advantages.

Why This Matters

- The SEC revised human capital disclosure rules to improve shareholder understanding of how HCM contributes to corporate value and strategy. However, early 10-Ks under the revised standards contain little information that is relevant for assessing these programs. Are companies being evasive, or are they still in the early stages of determining what information is relevant to the market? Are the SEC’s rules too discretionary, or will market pressure lead to better disclosure quality over time?

- The emphasis of early disclosure is on qualitative language. Can a company provide informative disclosure without publishing the underlying metrics that demonstrate HCM program effectiveness? Do companies not want to publish this data, or do they not track it?

- Comprehensive frameworks for human capital management cover all aspects of HCM, including recruitment, development, retention, satisfaction, safety, and compensation. While much of this information is useful to shareholders, it is also often considered proprietary. Our analysis shows that companies tend to cherry pick the categories of HCM that they disclose, and disclosure is rarely detailed and quantitative. Are companies being too protective? Is there a way to describe comprehensive HCM efforts in concise and informative language, supplemented with data, in a manner that does not reveal proprietary practices?

- Many companies state that employees are their most important asset. However, the chief human resources officer is rarely listed as a named executive officer and is often paid less than other executives in the C-suite. CEOs are also rarely given significant financial incentive to improve HCM practices. How can a company claim to value employees as an important asset without prioritizing investment in human capital systems? Is it a generic statement companies make to improve morale, or do they truly value—and invest in—their employee base? If the latter, why don’t they disclose information to demonstrate this?

The complete paper is available for download here.

Exhibit 1: Topic Areas Discussed in HCM Disclosure

Source: Forms 10-K, Securities and Exchange Commission. Sample includes the first 100 filers of Form 10-K following SEC rule revision in November 2020. Analysis by Equilar and the authors.

Exhibit 2: Metrics Provided in Disclosure

Source: Forms 10-K, Securities and Exchange Commission. Sample includes the first 100 filers of Form 10-K following SEC rule revision in November 2020. Analysis by Equilar and the authors.

Exhibit 3: HCM Metrics in CEO Annual Incentive Programs

Source: Forms DEF-14A, Securities and Exchange Commission. Sample includes the first 100 filers of Form 10-K following SEC rule revision in November 2020. Analysis by the authors.

Print

Print